North Korea

Democratic People's Republic of Korea | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: 애국가 Aegukka "The Patriotic Song" | |

Territory controlled

| |

| Capital and largest city | Pyongyang 39°2′N 125°45′E / 39.033°N 125.750°E |

| Official languages | Korean (Munhwaŏ) |

| Official script | Chosŏn'gŭl (Hangul) |

| Religion (2020) | |

Kim Tok Hun | |

| Choe Ryong-hae | |

| Pak In-chol | |

| Legislature | Supreme People's Assembly |

| Establishment history | |

• Gojoseon | 2333 BC (mythological) |

| 57 BC | |

| 668 | |

• Goryeo dynasty | 918 |

• Joseon dynasty | 17 July 1392 |

| 12 October 1897 | |

| 22 August 1910 | |

| 1 March 1919 | |

| 2 September 1945 | |

| 6 September 1945 | |

| 3 October 1945 | |

| 8 February 1946 | |

| 22 February 1947 | |

• DPRK established | 9 September 1948 |

| 27 December 1972 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 120,538[1] km2 (46,540 sq mi)[2][3] (98th) |

• Water (%) | 0.11 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | |

• 2008 census | |

• Density | 212/km2 (549.1/sq mi) (45th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | $40 billion[5] |

• Per capita | $1,800[6] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $16 billion[7] |

• Per capita | $640 |

| Currency | Korean People's won (₩) (KPW) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Pyongyang Time[8]) |

| Date format | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +850[9] |

| ISO 3166 code | KP |

| Internet TLD | .kp[10] |

North Korea,[c] officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK),[d] is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu (Amnok) and Tumen rivers, and South Korea to the south at the Korean Demilitarized Zone.[e] The country's western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its eastern border is defined by the Sea of Japan. North Korea, like its southern counterpart, claims to be the legitimate government of the entire peninsula and adjacent islands. Pyongyang is the capital and largest city.

The Korean Peninsula was first inhabited as early as the

North Korea is a

North Korea follows

Names

The modern spelling of Korea first appeared in the late 17th century in the travel writings of the Dutch East India Company's Hendrick Hamel.[12]

After the division of the country into North and South Korea, the two sides used different terms to refer to Korea: Chosun or Joseon (조선) in North Korea, and Hanguk (한국) in South Korea. In 1948, North Korea adopted Democratic People's Republic of Korea (

History

According to

From 1910 to the end of World War II in 1945, Korea was under Japanese rule. Most Koreans were peasants engaged in subsistence farming.[19] In the 1930s, Japan developed mines, hydro-electric dams, steel mills, and manufacturing plants in northern Korea and neighboring Manchuria.[20] The Korean industrial working class expanded rapidly, and many Koreans went to work in Manchuria.[21] As a result, 65% of Korea's heavy industry was located in the north, but, due to the rugged terrain, only 37% of its agriculture.[22]

Northern Korea had little exposure to modern, Western ideas.[23] One partial exception was the penetration of religion. Since the arrival of missionaries in the late nineteenth century, the northwest of Korea, and Pyongyang in particular, had been a stronghold of Christianity.[24] As a result, Pyongyang was called the "Jerusalem of the East".[25]

A Korean guerrilla movement emerged in the mountainous interior and in Manchuria, harassing the Japanese imperial authorities. One of the most prominent guerrilla leaders was the Communist Kim Il Sung.[26]

Founding

After the

Soviet forces withdrew from the North in 1948, and most American forces withdrew from the South in 1949. Ambassador Shtykov suspected Rhee was planning to invade the North and was sympathetic to Kim's goal of Korean unification under socialism. The two successfully lobbied Soviet leader Joseph Stalin to support a quick war against the South, which culminated in the outbreak of the Korean War.[28][29][30][31]

Korean War

The

A heavily guarded demilitarized zone (DMZ) still divides the peninsula, and an anti-communist and anti-North Korea sentiment remains in South Korea. Since the war, the United States has maintained a strong military presence in the South which is depicted by the North Korean government as an imperialist occupation force.[43] It claims that the Korean War was caused by the United States and South Korea.[44]

Post-war developments

The post-war 1950s and 1960s saw an ideologicial shift in North Korea, as Kim Il Sung sought to consolidate his power. Kim Il Sung was highly critical of Soviet premier

Industry was the favored sector in North Korea. Industrial production returned to pre-war levels by 1957. In 1959, relations with Japan had improved somewhat, and North Korea began allowing the repatriation of Japanese citizens in the country. The same year, North Korea revalued the North Korean won, which held greater value than its South Korean counterpart. Until the 1960s, economic growth was higher than in South Korea, and North Korean GDP per capita was equal to that of its southern neighbor as late as 1976.[52] However, by the 1980s, the economy had begun to stagnate; it started its long decline in 1987 and almost completely collapsed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, when all Soviet aid was suddenly halted.[53]

An internal CIA study acknowledged various achievements of the North Korean government post-war: compassionate care for war orphans and children in general, a radical improvement in the status of women, free housing, free healthcare, and health statistics particularly in life expectancy and infant mortality that were comparable to even the most advanced nations up until the North Korean famine.[54] Life expectancy in the North was 72 before the famine which was only marginally lower than in the South.[55] The country once boasted a comparatively developed healthcare system; pre-famine North Korea had a network of nearly 45,000 family practitioners with some 800 hospitals and 1,000 clinics.[56]

The relative peace between the North and South following the armistice was interrupted by border skirmishes, celebrity abductions, and assassination attempts. The North failed in several assassination attempts on South Korean leaders, such as in 1968, 1974, and the Rangoon bombing in 1983; tunnels were found under the DMZ and tensions flared over the axe murder incident at Panmunjom in 1976.[57] For almost two decades after the war, the two states did not seek to negotiate with one another. In 1971, secret, high-level contacts began to be conducted culminating in the 1972 July 4 South–North Joint Statement that established principles of working toward peaceful reunification. The talks ultimately failed because in 1973, South Korea declared its preference that the two Koreas should seek separate memberships in international organizations.[58]

Leadership of Kim Jong Il

The Soviet Union was dissolved on 26 December 1991, ending its aid and support to North Korea. In 1992, as Kim Il Sung's health began deteriorating, his son Kim Jong Il slowly began taking over various state tasks. Kim Il Sung died of a heart attack in 1994; Kim Jong Il declared a three-year period of national mourning, afterward officially announcing his position as the new leader.[59]

North Korea promised to halt its development of nuclear weapons under the Agreed Framework, negotiated with U.S. president Bill Clinton and signed in 1994. Building on Nordpolitik, South Korea began to engage with the North as part of its Sunshine Policy.[60][61] Kim Jong Il instituted a policy called Songun, or "military first".[62]

Flooding in the mid-1990s exacerbated the economic crisis, severely damaging crops and infrastructure and leading to widespread famine that the government proved incapable of curtailing, resulting in the deaths of between 240,000 and 420,000 people. In 1996, the government accepted UN food aid.[63]

The international environment changed once George W. Bush became U.S. President in 2001. His administration rejected South Korea's Sunshine Policy and the Agreed Framework. Bush included North Korea in his axis of evil in his 2002 State of the Union Address. The U.S. government accordingly treated North Korea as a rogue state, while North Korea redoubled its efforts to acquire nuclear weapons.[64][65][66] On 9 October 2006, North Korea announced it had conducted its first nuclear weapons test.[67][68]

U.S. President

Leadership of Kim Jong Un

- ^

- United States Congress (2016). North Korea: A Country Study. Nova Science Publishers. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-59033-443-0.

- "Han Chinese built four commanderies, or local military units, to rule the peninsula as far south as the Han River, with a core area at Lolang (Nangnang in Korean), near present-day P'yongyang. It is illustrative of the relentlessly different historiography practiced in North Korea and South Korea, as well as both countries' dubious projection backward of Korean nationalism, that North Korean historians denied that the Lolang district was centered in Korea and placed it northwest of the peninsula, possibly near Beijing."

- Connor, Edgar V. (2003). Korea: Current Issues and Historical Background. Nova Science Publishers. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-59033-443-0.

- "They place it northwest of the peninsula, possibly near Beijing, in order to de-emphasize China's influence on ancient Korean history."

- Kim, Jinwung 2012, p. 18

- "Immediately after destroying Wiman Chosŏn, the Han empire established administrative units to rule large territories in the northern Korean peninsula and southern Manchuria."

- Hyung, Hyung Il (2000). Constructing "Korean" Origins. Harvard University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-674-00244-9.

- "When material evidence from the Han commandery site excavated during the colonial period began to be reinterpreted by Korean nationalist historians as the first full-fledged "foreign" occupation in Korean history, Lelang's location in the heart of the Korean peninsula became particularly irksome because the finds seemed to verify Japanese colonial theories concerning the dependency of Korean civilization on China."

- Hyung, Hyung Il (2000). Constructing "Korean" Origins. Harvard University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-674-00244-9.

- "At present, the site of Lelang and surrounding ancient Han Chinese remains are situated in the North Korean capital of Pyongyang. Although North Korean scholars have continued to excavate Han dynasty tombs in the postwar period, they have interpreted them as manifestations of the Kochoson or the Koguryo kingdom."

- Xu, Stella Yingzi (2007). That glorious ancient history of our nation. University of California, Los Angeles. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-549-44036-9.

- "Lelang Commandery was crucial to understanding the early history of Korea, which lasted from 108 BCE to 313 CE around the Pyongyang area. However, because of its nature as a Han colony and the exceptional attention paid to it by Japanese colonial scholars for making claims of the innate heteronomy of Koreans, post 1945 Korean scholars intentionally avoided the issue of Lelang."

- Lee, Peter H. (1996). Sourcebook of Korean Civilization: Volume 2: From the Seventeenth Century to the Modern. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-231-07912-9.

- "But when Emperor Wu conquered Choson, all the small barbarian tribes in the northeastern region were incorporated into the established Han commanderies because of the overwhelming military might of Han China."

- United States Congress (2016). North Korea: A Country Study. Nova Science Publishers. p. 6.

References

Citations

- ^ "Korea, North". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 6 December 2023.

- ^ a b Demographic Yearbook – Table 3: Population by sex, rate of population increase, surface area and density (PDF). United Nations Statistics Division. 2012. p. 5. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ "North Korea country profile". BBC News. 17 October 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ "Korea North". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ CIA World Factbook.

- ^ CIA World Factbook. Archived from the originalon 25 June 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "UNData app". data.un.org.

- ^ "Decree on Redesignating Pyongyang Time". Naenara. 30 April 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Telephone System Field Listing". CIA The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ a b Hersher, Rebecca (21 September 2016). "North Korea Accidentally Reveals It Only Has 28 Websites". NPR. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ "Chapter I. Politics". . 2019 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Korea原名Corea? 美國改的名 (in Chinese). United Daily News. 5 July 2008. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-415-23749-9.

- ISBN 978-0-393-32702-1.

- ^ Young, Benjamin R (7 February 2014). "Why is North Korea called the DPRK?". NK News. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ "Early Korea". Archived from the original on 25 June 2015.

- ^

- 매국사학의 몸통들아, 공개토론장으로 나와라!. ngonews. 24 December 2015. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016.

- 요서 vs 평양… 한무제가 세운 낙랑군 위치 놓고 열띤 토론. Segye Ilbo. 21 August 2016. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017.

- "갈석산 동쪽 요서도 고조선 땅" vs "고고학 증거와 불일치". The Dong-a Ilbo. 22 August 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-674-61576-2.

- ISBN 978-0-393-32702-1.

- ISBN 978-0-393-32702-1.

- ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ^ Lone, Stewart; McCormack, Gavan (1993). Korea since 1850. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. pp. 184–185.

- ^ Lone, Stewart; McCormack, Gavan (1993). Korea since 1850. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. p. 175.

- ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ^ Lankov, Andrei (16 March 2005). "North Korea's missionary position". Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 18 March 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ^ "Administrative Population and Divisions Figures (#26)" (PDF). DPRK: The Land of the Morning Calm. Permanent Committee on Geographical Names for British Official Use. April 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ^ Lankov, Andrei (25 January 2012). "Terenti Shtykov: the other ruler of nascent N. Korea". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ Dowling, Timothy (2011). "Terentii Shtykov". History and the Headlines. ABC-CLIO. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Lankov, Andrei. "North Korea in 1945–48: The Soviet Occupation and the Birth of the State". From Stalin to Kim Il Sung – The Formation of North Korea, 1945–1960. pp. 2–3.

- The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. Oxford University Press. p. 7.

- ^ "United Nations Security Council – History". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "U.S.: N. Korea Boosting Guerrilla War Capabilities". Fox News Network, LLC. Associated Press. 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ISBN 978-1442226418.in Cambodia (1 to 2 million).

With three of the four major Cold War fault lines—divided Germany, divided Korea, divided China, and divided Vietnam – East Asia acquired the dubious distinction of having engendered the largest number of armed conflicts resulting in higher fatalities between 1945 and 1994 than any other region or sub-region. Even in Asia, while Central and South Asia produced a regional total of 2.8 million in human fatalities, East Asia's regional total is 10.4 million including the Chinese Civil War (1 million), the Korean War (3 million), the Vietnam War (2 million), and the Pol Pot genocide

- ISBN 978-0812978964.

Various encyclopedias state that the countries involved in the three-year conflict suffered a total of more than 4 million casualties, of which at least 2 million were civilians—a higher percentage than in World War II or Vietnam. A total of 36,940 Americans lost their lives in the Korean theater; of these, 33,665 were killed in action, while 3,275 died there of nonhostile causes. Some 92,134 Americans were wounded in action, and decades later, 8,176 were still reported as missing. South Korea sustained 1,312,836 casualties, including 415,004 dead. Casualties among other UN allies totaled 16,532, including 3,094 dead. Estimated North Korean casualties numbered 2 million, including about one million civilians and 520,000 soldiers. An estimated 900,000 Chinese soldiers lost their lives in combat.

- ISBN 978-1139486224.

In Korea, war in the early 1950s cost nearly 3 million lives, including nearly a million civilian dead in South Korea.

- ISBN 978-0415153164.

Before it ended, the Korean War cost over 3 million people their lives, including over 50,000 US servicemen and women and a much higher number of Chinese and Korean lives. The war also set in motion a number of changes that led to the militarization and intensification of the Cold War.

- ISBN 978-0199874231.

For the Korean War the only hard statistic is that of American military deaths, which included 33,629 battle deaths and 20,617 who died of other causes. The North Korean and Chinese Communists never published statistics of their casualties. The number of South Korean military deaths has been given as in excess of 400,000; the South Korean Ministry of Defense puts the number of killed and missing at 281,257. Estimates of communist troops killed are about one-half million. The total number of Korean civilians who died in the fighting, which left almost every major city in North and South Korea in ruins, has been estimated at between 2 and 3 million. This adds up to almost 1 million military deaths and a possible 2.5 million civilians who were killed or died as a result of this extremely destructive conflict. The proportion of civilians killed in the major wars of this century (and not only in the major ones) has thus risen steadily. It reached about 42 percent in World War II and may have gone as high as 70 percent in the Korean War. ... we find that the ratio of civilian to military deaths [in Vietnam] is not substantially different from that of World War II and is well below that of the Korean War.

- ^ Armstrong 2010, p. 1: "The number of Korean dead, injured or missing by war's end approached three million, ten percent of the overall population. The majority of those killed were in the North, which had half of the population of the South; although the DPRK does not have official figures, possibly twelve to fifteen percent of the population was killed in the war, a figure close to or surpassing the proportion of Soviet citizens killed in World War II."

- ISBN 978-0-393-31681-0.

- ^ Jager 2013, pp. 237–242.

- ^ Stewart, Richard W., ed. (2005). "The Korean War, 1950–1953". American Military History, Volume 2. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 30-22. Archived from the original on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- ^ Abt 2014, pp. 125–126.

- ISBN 978-0-313-28969-9.

- ^ Armstrong 2010, p. 9.

- ^ a b Chung, Chin O. Pyongyang Between Peking and Moscow: North Korea's Involvement in the Sino-Soviet Dispute, 1958–1975. University of Alabama, 1978, p. 45.

- ^ JSTOR 2643582.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. XV.

- ^ Schaefer, Bernd. "North Korean 'Adventurism' and China's Long Shadow, 1966–1972". Washington, D.C .: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2004.

- ISBN 0-8166-0345-6.

- ^ Armstrong, Charles. Tyranny of the Weak: North Korea and the World, 1950–1992. Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University. Cornell University Press. pp. 99–100.

- ^ Country Study 2009, pp. xxxii, 46.

- ^ French 2007, pp. 97–99.

- ISBN 978-1-59558-739-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-996429-1.

- ^ Demick, Barbara (16 July 2010). "North Korea's giant leap backwards". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Kirkbride, Wayne (1984). DMZ, a story of the Panmunjom axe murder. Hollym International Corp.

- ISBN 978-1-4128-4086-6. Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2016.

- ^ Chinoy, Mike (8 July 1997). "North Korea ends mourning for Kim Il Sung". CNN. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-7546-3653-3.

- ^ DeRouen, Karl; Heo, Uk (2005). Defense and Security: A Compendium of National Armed Forces and Security Policies. ABC-CLIO.

- ^ "North Korea's Military Strategy" Archived 24 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Parameters, U.S. Army War College Quarterly.

- ^ .

- ^ Jager 2013, p. 456.

- ^ Abt 2014, pp. 55, 109, 119.

- ISBN 978-0465031238.

- ^ Burns, Robert; Gearan, Anne (13 October 2006). "U.S.: Test Points to N. Korea Nuke Blast". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Bliss, Jeff (16 October 2006). "North Korea Nuclear Test Confirmed by U.S. Intelligence Agency". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 16 October 2006.

- ^ Lee, Sung-Yoon (26 August 2010). "The Pyongyang Playbook". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Anger at North Korea over sinking". BBC News. 20 May 2010. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Deok-hyun Kim (24 November 2010). "S. Korea to toughen rules of engagement against N. Korean attack". Archived from the original on 1 December 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ Korean Central News Agency. "Lee Myung Bak Group Accused of Scuttling Dialogue and Humanitarian Work". Archived from the original on 28 November 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ "North Korean leader Kim Jong Il, 69, has died". Associated Press. 19 December 2011. Archived from the original on 20 December 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ Albert, Eleanor (3 January 2018). "North Korea's Military Capabilities". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ Bierman, Noah (31 August 2017). "Trump warns North Korea of 'fire and fury'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ "N Korea promises Guam strike plan in days". BBC News. 10 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ a b Ji, Dagyum (12 February 2018). "Delegation visit shows N. Korea can take 'drastic' steps to improve relations: MOU". NK News. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Donald Trump meets Kim Jong Un in DMZ; steps onto North Korean soil. USA Today. 30 June 2019.

- ^ Hyonhee Shin (11 January 2021). "Mixed signals for North Korean leader's sister as Kim seeks to cement power". Reuters. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Seo, Yoonjung; Bae, Gawon; Jozuka, Emiko; Lendon, Brad (24 March 2022). "North Korea fires first suspected ICBM since 2017". CNN. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "North Korea declares itself a nuclear weapons state". BBC News. 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "조선로동당 중앙위원회 제8기 제9차전원회의 확대회의에 관한 보도". www.rodong.rep.kp. 로동신문. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "공화국의 부흥발전과 인민들의 복리증진을 위한 당면과업에 대하여". www.rodong.rep.kp. 로동신문. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "Topography and Drainage". Library of Congress. 1 June 1993. Archived from the original on 17 November 2004. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- ^ Song, Yong-deok (2007). "The recognition of mountain Baekdu in the Koryo dynasty and early times of the Joseon dynasty". History and Reality V.64.

- ^ United Nations Environmental Programme. "DPR Korea: State of the Environment, 2003" (PDF). p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2010.

- PMID 33293507.

- ^ Caraway, Bill (2007). "Korea Geography". The Korean History Project. Archived from the original on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- PMID 28608869.

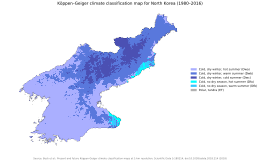

- ^ a b c "North Korea Country Studies. Climate". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ "North Korea country profile". BBC News. 9 April 2018.

- ^ "Kim Jong Un's North Korea: Life inside the totalitarian state". Washington Post.

- ^ "Totalitarianism". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-62513-171-3.

- ^ a b c "DPRK Socialist Constitution". www.naenara.com.kp. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Namgung Min (13 October 2008). "Kim Jong Il's Ten Principles: Restricting the People". Daily NK. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ Audrey Yoo (16 October 2013). "North Korea rewrites rules to legitimise Kim family succession". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ "북한 노동당 규약 주요 개정 내용" [Major revisions to North Korea's Workers' Party rules]. Yonhap News Agency. 1 June 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Na, Hye-yoon (6 January 2021). 北, 당원 대폭 늘었나 ... 당 대회 참석수로 '650만 명' 추정 [Has party membership surged in the north? Estimated attendance of '6.5 million' at party convention]. News1 Korea (in Korean). Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 192.

- ^ Petrov, Leonid (12 October 2009). "DPRK has quietly amended its Constitution". Korea Vision. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ a b "North Korea profile: Leaders". BBC News. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ "North Korea: Kim Jong-un hailed 'supreme commander'". BBC News. 24 December 2011. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (24 December 2007). "Why has the Bush administration lost interest in North Korea?". Slate. Archived from the original on 20 May 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ Article 109 of the Constitution of North Korea

- ^ "DPRK Constitution Text Released Following 2016 Amendments". North Korea Leadership Watch. 4 September 2016. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ a b "Organizational Chart of North Korean Leadership" (PDF). Seoul: Political and Military Analysis Division, Intelligence and Analysis Bureau; Ministry of Unification. January 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "North Korea | Facts, Map, & History | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 7 February 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ISBN 978-9946-0-1099-1. Archived from the original(PDF) on 22 August 2016. Amended and supplemented on 1 April, Juche 102 (2013), at the Seventh Session of the Twelfth Supreme People's Assembly.

- ^ Choe Sang-Hun (9 March 2014). "North Korea Uses Election To Reshape Parliament". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Hotham, Oliver (3 March 2014). "The weird, weird world of North Korean elections". NK News. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "North Korea election turnout 99.99 percent: State media". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "North Korea elections: What is decided and how?". BBC News. 19 July 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b "North Korea's premier now ranks as top official. Is he Kim Jong Un's successor?". NK PRO. 1 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 198.

- ^ Country Study 2009, pp. 197–198.

- ^ "Pak Opens Account with Conservative Aire". Daily NK. 23 April 2013. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 200.

- ^ 국가법령정보센터 | 법령 > 본문 – 대한민국헌법. www.law.go.kr (in Korean). Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Hallam, Jonny; Magramo, Kathleen; Seo, Yoonjung (20 March 2023). "Kim says North Korea must be ready to launch nuclear counterattack as daughter watches latest missile test". CNN.

North Korea has been ruled as a hereditary dictatorship since its founding in 1948 by Kim Il Sung. His son, Kim Jong Il, took over after his father's death in 1994. And Kim Jong Un took power 17 years later when Kim Jong Il died.

- .

- ^ Flannery, Nathaniel Parish (25 May 2016). "Most Corrupt Countries". Forbes. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ Spencer, Richard (28 August 2007). "North Korea power struggle looms". The Telegraph (online version of United Kingdom's national newspaper). London. Archived from the original on 20 November 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

A power struggle to succeed Kim Jong-il as leader of North Korea's Stalinist dictatorship may be looming after his eldest son was reported to have returned from semi-voluntary exile.

- ^ Parry, Richard Lloyd (5 September 2007). "North Korea's nuclear 'deal' leaves Japan feeling nervous". The Times (online version of United Kingdom's national newspaper of record). London. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

The US Government contradicted earlier North Korean claims that it had agreed to remove the Stalinist dictatorship's designation as a terrorist state and to lift economic sanctions, as part of talks aimed at disarming Pyongyang of its nuclear weapons.

- ^ Brooke, James (2 October 2003). "North Korea Says It Is Using Plutonium to Make A-Bombs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

North Korea, run by a Stalinist dictatorship for almost six decades, is largely closed to foreign reporters and it is impossible to independently check today's claims.

- ^ "A portrait of North Korea's new rich". The Economist. 29 May 2008. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

EVERY developing country worth its salt has a bustling middle class that is transforming the country and thrilling the markets. So does Stalinist North Korea.

- ^ Alton & Chidley 2013.

- ^ a b Country Study 2009, p. 203.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 204.

- ^ Wikisource:Constitution of North Korea (1972)

- ^ Martin 2004, p. 111: "Although it was in that 1955 speech that Kim Il-sung gave full voice to his arguments for juche, he had been talking along similar lines as early as 1948."

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 206.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 186.

- ^ Herskovitz, Jon; Kim, Christine (28 September 2009). "North Korea drops communism, boosts "Dear Leaders"". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ JH Ahn (30 June 2016). "N.Korea updates constitution expanding Kim Jong Un's position". NK News.

- ^ 권, 영전 (1 June 2021). [표] 북한 노동당 규약 주요 개정 내용. Yonhap News Agency (in Korean). Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 207.

- ^ Lankov, Andrei (4 December 2009). "Review of The Cleanest Race". Far Eastern Economic Review. Archived from the original on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (1 February 2010). "Kim Jong-il's regime is even weirder and more despicable than you thought". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Myers, Brian Reynolds (1 October 2009). "The Constitution of Kim Jong Il". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

From its beginnings in 1945 the regime has espoused—to its subjects if not to its Soviet and Chinese aid-providers—a race-based, paranoid nationalism that has nothing to do with Marxism-Leninism. [...] North Korea has always had less in common with the former Soviet Union than with the Japan of the 1930s, another 'national defense state' in which a command economy was pursued not as an end in itself, but as a prerequisite for rapid armament. North Korea is, in other words, a national-socialist country

- ^ "Kim Il-Sung | Biography, Facts, Leadership of North Korea, Significance, & Death | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 17 May 2023.

- ^ The Twisted Logic of the N.Korean Regime Archived 13 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Chosun Ilbo. 13 August 2013. Accessed date: 11 January 2017.

- ^ "We have just witnessed a coup in North Korea". New Focus International. 27 December 2013. Archived from the original on 26 January 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ Myers 2011, p. 100.

- ^ Myers 2011, p. 113.

- ^ Martin 2004, p. 353.

- ^ Myers 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Myers 2011, p. 114, 116.

- ISBN 978-0-465-01101-8.

- ^ Martin 2004, p. 105.

- ^ "DEATH OF A LEADER: THE SCENE; In Pyongyang, Crowds of Mourners Gather at Kim Statue". The New York Times. 10 July 1994. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- ^ McCurry, Justin (19 December 2011). "North Koreans' reaction to Kim Jong-il's death is impossible to gauge". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ "North Korea marks leader's birthday". BBC. 16 February 2002. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Mansourov, Alexandre. "Korean Monarch Kim Jong Il: Technocrat Ruler of the Hermit Kingdom Facing the Challenge of Modernity". The Nautilus Institute. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ LaBouyer, Jason (May/June 2005) "When friends become enemies – Understanding left-wing hostility to the DPRK" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2009., Lodestar, pp. 7–9. Korea-DPR.com. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Lankov, Andrei (10 June 2015). "N Korea: Tuning into the 'hermit kingdom'". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- Yonhap News (in Korean). 2 March 2009. Archived from the originalon 29 April 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- ^ a b Wertz, Daniel; JJ Oh; Kim Insung (August 2015). "Issue Brief: DPRK Diplomatic Relations" (PDF). The National Committee on North Korea. pp. 1–7, n4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "A Single Flag – North And South Korea Join U.N. And The World". The Seattle Times. 17 September 1991. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. 20 February 2014. Archived from the originalon 6 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Commission de la défense nationale et des forces armées (30 March 2010). "Audition de M. Jack Lang, envoyé spécial du Président de la République pour la Corée du Nord" (in French). Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Kennedy, Pamela (14 May 2019). "Taiwan and North Korea: Star-Crossed Business Partners". 38 North. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- OCLC 48536955.

- ^ Seung-Ho Joo, Tae-Hwan Kwak - Korea in the 21st Century

- ^ "North Korea recognises breakaway of Russia's proxies in east Ukraine". Reuters. 13 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- JSTOR 43908855.

- ^ Shih, Gerry; Denyer, Simon (17 June 2019). "China's Xi to visit North Korea as both countries lock horns with United States". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Understanding the China-North Korea Relationship". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ Shi, Jiangtao; Chan, Minnie; Zheng, Sarah (27 March 2018). "Kim's visit evidence China, North Korea remain allies, analysts say". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ "Kim Yong Nam Visits 3 ASEAN Nations To Strengthen Traditional Ties". The People's Korea. 2001. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ "A New U.N. Vote Shows Russia Isn't as Isolated as the West May Like to Think". Time. 13 October 2022.

- ^ "Putin thanks North Korea for supporting Ukraine war as Pyongyang displays its nukes in parade". CNN. 28 July 2023.

- ^ Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism (30 April 2008). "Country Reports on Terrorism: Chapter 3 – State Sponsors of Terrorism Overview". Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ "Country Guide". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ "U.S. takes North Korea off terror list". CNN. 11 October 2008. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ "Trump declares North Korea 'sponsor of terror'". BBC News. 20 November 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "N Korea to face Japan sanctions". BBC News. 13 June 2006. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Everett (12 June 2018). "Read the full text of the Trump-Kim agreement here". CNBC. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Everett (28 February 2019). "Trump-Kim summit was cut short after North Korea demanded an end to all sanctions". CNBC. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ "Donald Trump meets Kim Jong Un in DMZ; steps onto North Korean soil". USA Today. 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Koreas agree to military hotline". CNN. 4 June 2004. Archived from the original on 30 November 2009. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 218.

- ^ Kim, Il Sung (10 October 1980). "REPORT TO THE SIXTH CONGRESS OF THE WORKERS' PARTY OF KOREA ON THE WORK OF THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE". Songun Politics Study Group (USA). Archived from the original on 29 August 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ "North Korea (11/05)". U.S. Department of State.

- ^ Koreans disagree on aid by North Archived 18 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine – NY Times

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 220.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 222.

- ^ "North-South Joint Declaration". Naenara. 15 June 2000. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ "Factbox – North, South Korea pledge peace, prosperity". Reuters. 4 October 2007. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "North Korea tears up agreements". BBC News. 30 January 2009. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- ^ "North Korea deploying more missiles". BBC News. 23 February 2009. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010.

- ^ "North Korea warning over satellite". BBC News. 3 March 2009. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- ^ Text from North Korea statement Archived 5 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine, by Jonathan Thatcher, Reuters, 25 May 2010

- ^ Branigan, Tania; MacAskill, Ewen (23 November 2010). "North Korea: a deadly attack, a counter-strike – now Koreans hold their breath". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen (29 March 2013). "US warns North Korea of increased isolation if threats escalate further". The Guardian. Washington, DC. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ "South Korea's likely next president warns the U.S. not to meddle in its democracy". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2 May 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ "Koreas make nuclear pledge after summit". BBC News. 27 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "North Korea's Kim says to scrap missile sites, visit Seoul". Reuters. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ "North Korea's Kim Jong Un abandons unification goal with South". BBC News. 16 January 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ "North Korea's Kim shuts agencies working for reunification with South Korea". Al Jazeera English. 16 January 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ "Legal System field listing". CIA The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ a b Country Study 2009, p. 274.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 201.

- ^ "Outside World Turns Blind Eye to N. Korea's Hard-Labor Camps". The Washington Post. 20 July 2009. Archived from the original on 19 September 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 276.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 277.

- ^ Country Study 2009, pp. 277–278.

- ^ "North Korea: A case to answer – a call to act" (PDF). Christian Solidarity Worldwide. 20 June 2007. pp. 25–26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Subcommittee on International Human Rights, 40th Parliament, 3rd session, February 1, 2011: Testimony of Ms. Hye Sook Kim". Parliament of Canada. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ "The Hidden Gulag – Exposing Crimes against Humanity in North Korea's Vast Prison System" (PDF). The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ a b Country Study 2009, p. 272.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 273.

- ^ Kim Yonho (2014). Cell Phones in North Korea (PDF). pp. 35–38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ "Report: Torture, starvation rife in North Korea political prisons". CNN. 4 May 2011. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014.

- ^ Kirby, Darusman & Biserko 2014, p. 346.

- ^ Amnesty International (2007). "Our Issues, North Korea". Human Rights Concerns. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ a b Kay Seok (15 May 2007). "Grotesque indifference". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ a b "Human Rights in North Korea". hrw.org. Human Rights Watch. 17 February 2009. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- ^ Country Study 2009, pp. 272–273.

- ^ U.S. Department of State(17 June 2020).

- ^ "Annual Report 2011: North Korea". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ a b "North Korea: Freedom of Movement, Opinion and Expression". Amnesty International. 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "North Korea". www.amnesty.org. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 278.

- ^ a b "North Korea: Political Prison Camps". Amnesty International. 4 May 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Concentrations of Inhumanity (p. 40–44)" (PDF). Freedom House, May 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Survey Report on Political Prisoners' Camps in North Korea (p. 58–73)" (PDF). National Human Rights Commission of Korea, December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "North Korea: Catastrophic human rights record overshadows 'Day of the Sun'". Amnesty International. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Images reveal scale of North Korean political prison camps". Amnesty International. 3 May 2011. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Report on political prisoners in North soon"[usurped] article by Han Yeong-ik in Korea Joongang Daily 30 April 2012

- ^ "North Korea: UN Commission documents wide-ranging and ongoing crimes against humanity, urges referral to ICC". United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 17 February 2014. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ Kirby, Darusman & Biserko 2014.

- ^ Walker, Peter (17 February 2014). North Korean human rights abuses recall Nazis, says UN inquiry chair Archived 18 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ "Human Rights Groups Call on UN Over N.Korea Gulag". The Chosunilbo. 4 April 2012. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Maps | Global Slavery Index". www.globalslaveryindex.org.

- ^ "North Korea". The Global Slavery Index. Walk Free Foundation. 2016. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ "Asia-Pacific". Global Slavery Index 2016. The Minderoo Foundation. 2016. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ "UN uncovers torture, rape and slavery in North Korea". The Times. 15 February 2014.

- ^ North Korean 'worker brigades' in Russia, BBC, 15 July 2015, retrieved 31 October 2023

- Dw.com. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ Tycho A. van der Hoog (2018). "Uncovering North Korean Forced Labour in Africa: Towards a Research Framework". Leiden University.

- AP Archive, 2 August 2017, retrieved 31 October 2023

- ^ John Sifton; Tom Lantos (29 April 2015). "North Korea's Forced Labor Enterprise: A State-Sponsored Marketplace in Human Trafficking". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ a b "North Korea defends human rights record in report to UN". BBC News. 8 October 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ a b Taylor, Adam (22 April 2014). "North Korea slams U.N. human rights report because it was led by gay man". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ a b "KCNA Commentary Slams Artifice by Political Swindlers". kcna.co.jp. Korean Central News Agency. 22 April 2014. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ KCNA Assails Role Played by Japan for UN Passage of "Human Rights" Resolution against DPRK Archived 1 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, KCNA, 22 December 2005.

- ^ KCNA Refutes U.S. Anti-DPRK Human Rights Campaign Archived 1 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, KCNA, 8 November 2005.

- ^ a b "February 2012 DPRK (North Korea)". United Nations Security Council. February 2012.

- ^ a b "The State of the North Korean Military". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 2020.

- ^ a b Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs (April 2007). "Background Note: North Korea". United States Department of State. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ a b "Armed forces: Armied to the hilt". The Economist. 19 July 2011. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ "Army personnel (per capita) by country". NationMaster. 2007. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 239.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 247.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 248.

- ^ Country Profile 2007, p. 19 – Major Military Equipment.

- ^ "Worls militaries: K". soldiering.ru. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ a b Country Study 2009, pp. 288–293.

- ISBN 978-0-89206-632-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2011.weapons.

The DPRK has implosion fission

- ^ "How the Nuclear Missile Threat from North Korea Keeps Growing". Bloomberg.com. 1 August 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Hipwell, Deirdre (24 April 2009). "North Korea is fully fledged nuclear power, experts agree". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ Ryall, Julian (9 August 2017). "How far can North Korean missiles travel? Everything you need to know". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 260.

- ^ "New Threat from N. Korea's 'Asymmetrical' Warfare". The Chosun Ilbo. 29 April 2010. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- ^ "UN Documents for DPRK (North Korea): Security Council Resolutions [View All Security Council Resolutions]". securitycouncilreport.org. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ "North Korea's military aging but sizable". CNN. 25 November 2010. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "N.Korea Developing High-Powered GPS Jammer". The Chosun Ilbo. 7 September 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ "North Korea's Human Torpedoes". Daily NK. 6 May 2010. Archived from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "North Korea 'develops stealth paint to camouflage fighter jets'". The Daily Telegraph. 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 16 September 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "N.Korea Boosting Cyber Warfare Capabilities". The Chosun Ilbo. 5 November 2013. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ a b Kwek, Dave Lee and Nick (29 May 2015). "North Korean hackers 'could kill'". BBC News.

- ^ "Satellite in Alleged NK Jamming Attack". Daily NK. 15 November 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ "Defense". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ "Report on Implementation of 2009 Budget and 2010 Budget". Korean Central News Agency. 9 April 2010. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011.

- ^ "N. Korea ranks No. 1 for military spending relative to GDP: State Department report". Yonhap News Agency. 23 December 2016.

- ^ "North Korea Confirms Test of New Type of Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missile – October 20, 2021". Daily News Brief. 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ "World Population Prospects – Population Division – United Nations". population.un.org. Archived from the original on 6 May 2011.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- CIA World Factbook. Archived from the originalon 25 June 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Country Study 2009, p. 69.

- ^ "Foreign Assistance to North Korea: Congressional Research Service Report for Congress" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. 26 April 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ Solomon, Jay (20 May 2005). "US Has Put Food Aid for North Korea on Hold". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 16 February 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d Country Study 2009, p. xxii.

- ^ "Asia-Pacific : North Korea". Amnesty International. 2007. Archived from the original on 29 May 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ "National Nutrition Survey final report". The United Nations Office in DPR Korea. 19 March 2013. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "The State of North Korean Farming: New Information from the UN Crop Assessment Report". 38 North. 18 December 2013. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "Korea, Democratic People's Republic (DPRK) | WFP | United Nations World Food Programme – Fighting Hunger Worldwide". WFP. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ISSN 1551-2789.

- CIA World Factbook. Archived from the originalon 25 June 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- CIA World Factbook. Archived from the originalon 4 August 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ a b c "North Korea Census Reveals Poor Demographic and Health Conditions". Population Reference Bureau. December 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "UN HDR 2020 PDF" (PDF).

- ^ PMID 23766868.

- ^ "Cause of death, by non-communicable diseases (% of total) – Korea, Dem. People's Rep. | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Cause of death, by communicable diseases and maternal, prenatal and nutrition conditions (% of total) – Korea, Dem. People's Rep., Korea, Rep., Low income, High income | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b "North Korea". Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 9 September 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Maternal mortality ratio (modeled estimate, per 100,000 live births) – Korea, Dem. People's Rep., Low income, Middle income | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Healthcare Access and Quality Index". Our World in Data. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Life Inside North Korea". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- ^ "Democratic People's Republic of Korea: WHO statistical profile" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- ^ "Physicians (per 1,000 people) – Low income, Korea, Dem. People's Rep., Korea, Rep. | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "Aid agencies row over North Korea health care system". BBC News. 16 July 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ a b Country Profile 2007, pp. 7–8.

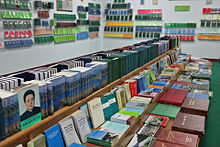

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Cha, Victor (2012). The Impossible State. Ecco.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 126.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 122.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 123.

- ^ "Educational themes and methods". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 124.

- ^ a b "The Korean Language". Library of Congress Country Studies. June 1993. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ]

- ^ Alton & Chidley 2013, p. 89.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 18.

- ISBN 9780761476313. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

North Korea is officially an atheist state in which almost the entire population is nonreligious.

- ISBN 9780671793760. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

Atheism continues to be the official position of the governments of China, North Korea and Cuba.

- ^ a b Boer 2019, p. 216.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 115.

- ^ "Human Rights in North Korea". Human Rights Watch. July 2004. Archived from the original on 1 December 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ "Constitution of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea" (PDF).

- ^ a b Boer 2019, p. 233.

- ^ "Open Doors International : WWL: Focus on the Top Ten". Open Doors International. Open Doors (International). Archived from the original on 22 June 2007. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ "2020 Report on International Religious Freedom: Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK)". Office of International Religious Freedom. U.S. Department of State.

- ^ "Freedom of Ideas and Religious Belief in DPRK". Paektu Solidarity Alliance. 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Inside North Korea's only Mosque During Eid al-Fitr". 18 May 2021.

- ^ United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (21 September 2004). "Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom". Nautilus Institute. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ "N Korea stages Mass for Pope". BBC News. 10 April 2005. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 14.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 120.

- ^ a b c Collins, Robert (6 June 2012). Marked for Life: Songbun, North Korea's Social Classification System (PDF). Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ a b McGrath, Matthew (7 June 2012). "Marked for Life: Songbun, North Korea's Social Classification System". NK News. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ Winzig, Jerry. "A Look at North Korean Society" (book review of 'Kim Il-song's North Korea' by Helen-Louise Hunter). winzigconsultingservices.com. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

In North Korea, one's songbun, or socio-economic and class background, is extremely important and is primarily determined at birth. People with the best songbun are descendants of the anti-Japanese guerrillas who fought with Kim Il-sung, followed by people whose parents or grandparents were factory workers, laborers, or poor, small farmers in 1950. "Ranked below them in descending order are forty-seven distinct groups in what must be the most class-differentiated society in the world today." Anyone with a father, uncle, or grandfather who owned land or was a doctor, Christian minister, merchant, or lawyer has low songbun.

- The Huffington Post. Archived from the originalon 28 January 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ^ KINU White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2011, pp. 216, 225. Kinu.or.kr (30 August 2011). Retrieved on 6 April 2013.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 135.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 138.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 142.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 140.

- ^ a b c d e "Economy". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Country Study 2009, pp. 143, 145.

- ^ Country Profile 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 145.

- ^ "GDP Composition by sectory field listing". CIA The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "Filling Gaps in the Human Development Index" (PDF). United Nations ESCAP. February 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2011.

- ^ "North Korean Economy Records Positive Growth for Two Consecutive Years". The Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 17 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ North Korea Handbook 2003, p. 931.

- ^ "Report: North Korea economy developing dramatically despite sanctions". UPI. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. xxiii.

- ^ Country Study 2007, p. 152.

- ^ "Pyongyang glitters but most of North Korea still dark". AP through MSN News. 28 April 2013. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ Jangmadang Will Prevent "Second Food Crisis" from Developing Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, DailyNK, 26 October 2007

- ^ 2008 Top Items in the Jangmadang Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The DailyNK, 1 January 2009

- ^ Kim Jong Eun's Long-lasting Pain in the Neck Archived 3 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, TheDailyNK, 30 November 2010

- ^ "NK is no Stalinist country". The Korea Times. 9 October 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ "Labor Force by occupation field listing". CIA The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ "Labor Force field listing". CIA The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ "Major Industries field listing". CIA The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ In limited N.Korean market, furor for S.Korean products Archived 9 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Hankyoreh, 6 January 2011

- ^ Bermudez, Joseph S. Jr. (14 December 2015). North Korea's Exploration for Oil and Gas (Report). 38 North. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 154.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 143.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 47.

- ^ French 2007, p. 155.

- ^ Paris, Natalie (20 February 2013). "North Korea welcomes increase in tourism". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ "Skiing in North Korea: Mounting Problems". The Economist. 14 February 2014. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ "North Korea temporarily closes border until further notice – Coronavirus precaution". Young Pioneer Tours. January 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 173.

- ^ Boydston, Kent (1 August 2017). "North Korea's Trade and the KOTRA Report". Peterson Institute for International Economics. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 165.

- ^ "North Korea's crusade for more special economic zones". NK News. 1 December 2013. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ "North Korea Plans To Expand Special Economic Zones". The Huffington Post. 16 November 2013. Archived from the original on 12 April 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ "Cumulative output of Kaesong park reaches US$2.3 bln". Yonhap News Agency. 12 June 2014. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ "India is North Korea's second biggest trading partner after China". Moneycontrol. 16 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ "Russia, North Korea Agree to Settle Payments in Rubles in Trade Pact". RIA Novosti. 28 March 2014. Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ "North Korean Foreign Trade Volume Posts Record High of USD 7.3 Billion in 2013". The Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 28 May 2014. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ "South Korea has lost the North to China". Financial Times. 20 February 2014. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ Schielke, Thomas (17 April 2018). "How Satellite Images of the Earth at Night Help Us Understand Our World and Make Better Cities". ArchDaily. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 146.

- ^ Wee, Heesun (11 April 2019). "Kim Jong Un is skirting sanctions and pursuing this energy strategy to keep North Korea afloat". CNBC. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d Country Study 2009, p. 147.

- ^ a b "North Korea to Utilize Science and Technology to Overcome Its Energy Crisis". The Institute of Far Eastern Studies. 3 April 2014. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ "North Korea Adopts Renewable Energy Law". The Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 17 September 2013. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ "Progress in North Korea's Renewable Energy Production". NK Briefs. The Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 2 March 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ "Activity Seen at North Korean Nuclear Plant". The New York Times. 24 December 2013. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ "High Speed Rail and Road Connecting Kaesong-Pyongyang-Sinuiju to be Built". The Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 20 December 2013. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ "Roadways field listing". CIA The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 150.

- ^ "Merchant marine field listing". CIA The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "Airports field listing". CIA The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "Helipads field listing". CIA The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "Cars on Pyongyang streets can tell us a lot about the country". EJ Insight. 23 May 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "70% of Households Use Bikes". Daily NK. 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "North Korea's bike path". NK News. 21 March 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Lankov, Andrei (1 April 2007). "Academies". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ a b "North Korea to Become Strong in Science and Technology by Year 2022". The International Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 21 December 2012. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ N. Korea moves to develop cutting-edge nanotech industry Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine Yonhap News – 2 August 2013 (access date: 17 June 2014)

- ^ "Two Koreas can cooperate in chemistry, biotech and nano science: report". Yonhap News Agency. 6 January 2010. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ "High-Tech Development Zones: The Core of Building a Powerful Knowledge Economy Nation". The International Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 5 June 2014. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ ". 'Miraewon' Electronic Libraries to be Constructed Across North Korea". The International Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 22 May 2014. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Pearlman, Robert (2 April 2014). "North Korea's 'NADA' Space Agency, Logo Are Anything But 'Nothing'". Space.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-322-0732-0.

- ^ Talmadge, Eric (18 December 2012). "Crippled NKorean probe could orbit for years". AP. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Japan to launch spy satellite to keep an eye on North Korea". Wired. 23 January 2013. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ "High five: Messages from North Korea". The Asia Times. 19 March 2009. Archived from the original on 23 March 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Walker, Peter (1 April 2014). "North Korea appears to ape Nasa with space agency logo". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ "UN Security Council vows new sanctions after N Korea's rocket launch". BBC News. 7 February 2016. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "Country Comparison: Telephones – main lines in use". The World Factbook. CIA. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016.

- ^ French 2007, p. 22.

- ^ a b c "North Korea embraces 3G service". BBC. 26 April 2013. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ MacKinnon, Rebecca (17 January 2005). "Chinese Cell Phone Breaches North Korean Hermit Kingdom". Yale Global Online. Archived from the original on 9 October 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ a b "North Korea: On the net in world's most secretive nation". BBC. 10 December 2012. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Lintner, Bertil (24 April 2007). "North Korea's IT revolution". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 27 April 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b "North Korea has 'Bright' idea for internet". News.com.au. 4 February 2014. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Bryant, Matthew (19 September 2016). "North Korea DNS Leak". Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-395-25812-5.

- ^ Bruce G. Cumings. "The Rise of Korean Nationalism and Communism". A Country Study: North Korea. Library of Congress. Call number DS932 .N662 1994. Archived from the original on 10 April 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Contemporary Cultural Expression". Library of Congress Country Studies. 1993. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ North Korea Handbook 2003, pp. 496–497.

- ^ "Democratic People's Republic of Korea". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ a b Lankov, Andrei (13 February 2011). "Socialist realism". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Rank, Michael (16 June 2012). "A window into North Korea's art world". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 26 March 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b "Mansudae Art Studio, North Korea's Colossal Monument Factory". Bloomberg Business Week. 6 June 2013. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "Senegal President Wade apologises for Christ comments". BBC News. London. 31 December 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "Heroes' monument losing battle". The Namibian. 5 June 2005. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "Complex of Koguryo Tombs". unesco.org. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ a b c "Literature, Music, and Film". Library of Congress Country Studies. 1993. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ a b Melvin, Sheila (28 July 2010). "North Korean Opera Draws Acclaim in China". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "Revolutionary opera 'Sea of Blood' 30 years old". KCNA. August 2001. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "North Korea: Bringing modern music to Pyongyang". BBC News. 3 January 2013. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "Meet North Korea's new girl band: five girls who just wanna have state-sanctioned fun". The Telegraph. 29 May 2013. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ North Korea Handbook 2003, p. 478.

- ^ "Moranbong: Kim Jong-un's favourite band stage a comeback". The Guardian. 24 April 2014. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Hoban, Alex (1 February 2011). "Pyongyang goes pop: How North Korea discovered Michael Jackson". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-351-10410-4.

- ^ North Korea Handbook 2003, pp. 423–424.

- ^ North Korea Handbook 2003, p. 424.

- ^ Park, Han-na (24 June 2020). "North Korea lauds Harry Potter". The Korea Herald.

- ^ North Korea Handbook 2003, p. 475.

- ^ "Benoit Symposium: From Pyongyang to Mars: Sci-fi, Genre, and Literary Value in North Korea". SinoNK. 25 September 2013. Archived from the original on 13 June 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ a b Country Study 2009, p. 114.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 94.

- ^ Hoban, Alex (22 February 2011). "Pyongyang goes pop: Inside North Korea's first indie disco". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Kretchun, Nat; Kim, Jane (10 May 2012). "A Quiet Opening: North Koreans in a Changing Media Environment" (PDF). InterMedia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

The primary focus of the study was on the ability of North Koreans to access outside information from foreign sources through a variety of media, communication technologies and personal sources. The relationship between information exposure on North Koreans' perceptions of the outside world and their own country was also analyzed.

- ^ Harvard International Review. Winter 2016, Vol. 37 Issue 2, pp. 46–50.

- ^ Crocker, L. (22 December 2014). North Korea's Secret Movie Bootleggers: How Western Films Make It Into the Hermit Kingdom.

- ^ a b Journalists, C. T. (25 April 2017). "North Korean censorship".

- ^ "North Korea". Reporters Without Borders. 2017. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ "Freedom of the Press: North Korea". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-60021-655-8.

- ^ "Meagre media for North Koreans". BBC News. 10 October 2006. Archived from the original on 20 August 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "North Korea Uses Twitter, YouTube For Propaganda Offensive". The Huffington post. 17 August 2010. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Calderone, Michael (14 July 2014). "Associated Press North Korea Bureau Opens As First All-Format News Office In Pyongyang". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ a b O'Carroll, Chad (6 January 2014). "North Korea's invisible phone, killer dogs and other such stories – why the world is transfixed". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (29 August 2013). "Why You Shouldn't Necessarily Trust Those Reports Of Kim Jong-un Executing His Ex-Girlfriend". businessinsider.com. Business Insider. Archived from the original on 19 January 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Fisher, Max (3 January 2014). "No, Kim Jong Un probably didn't feed his uncle to 120 hungry dogs". Washington Post. Washington, DC. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014.

- ^ Korean Cuisine (한국요리 韓國料理) (in Korean). Naver / Doosan Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 July 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Food". Korean Culture and Information Service. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7864-2839-7.

- ^ "Okryu Restaurant Becomes More Popular for Terrapin Dishes". Korean Central News Agency. 26 May 2010. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Okryu restaurant". Korean Central News Agency. 31 August 1998. Archived from the original on 8 January 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "The mystery of North Korea's virtuoso waitresses". BBC News. 8 June 2014. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Fifa investigates North Korea World Cup abuse claims". BBC News. 11 August 2010. Archived from the original on 29 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "When Middlesbrough hosted the 1966 World Cup Koreans". BBC News. 15 June 2010. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Rodman returns to North Korea amid political unrest". Fox News. 19 December 2013. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ "Democratic People's Republic of Korea". International Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "North Korea's Kim Un Guk wins 62kg weightlifting Olympic gold". BBC News. 30 July 2012. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "North Korea rewards athletes with luxury apartments". Reuters. 4 October 2013. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ a b "North Korea halts showcase mass games due to flood". Reuters. 27 August 2007. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009.

- ^ a b Watts, Jonathan (17 May 2002). "Despair, hunger and defiance at the heart of the greatest show on earth". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Ryall, Julian (26 September 2013). "Kim Jong-un orders spruce up of world's biggest stadium as 'millions starve'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 June 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Demetriou, Danielle (3 April 2014). "North Korea allows tourists to run in Pyongyang marathon for the first time". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

General and cited sources

- "Country Profile: North Korea" (PDF). Library of Congress – Federal Research Division. July 2007. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- Abt, Felix (2014). A Capitalist in North Korea: My Seven Years in the Hermit Kingdom. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9780804844390.

- Alton, David; Chidley, Rob (2013). Building Bridges: Is There Hope for North Korea?. Oxford: Lion Books. ISBN 978-0-7459-5598-8.

- Armstrong, Charles K. (20 December 2010). "The Destruction and Reconstruction of North Korea, 1950–1960" (PDF). The Asia-Pacific Journal. 8 (51). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Armstrong, Charles K. "North Korea in 2016." Asian Survey 57.1 (2017): 119–27. abstract

- Boer, Roland (2019). Red theology : on the Christian Communist tradition. Boston: OCLC 1078879745.

- French, Paul (2007). North Korea: The Paranoid Peninsula: A Modern History (Second ed.). London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-905-7.

- Hayes, Peter, and Roger Cavazos. "North Korea in 2015." Asian Survey 56.1 (2016): 68–77. abstract

- Hayes, Peter, and Roger Cavazos. "North Korea in 2014." Asian Survey 55.1 (2015): 119–31. abstract; also full text online

- Jackson, Van (2016). Rival Reputations: Coercion and Credibility in US–North Korea Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-13331-0., covers 1960s to 2010.

- Jackson, Van. "Deterring a Nuclear-Armed Adversary in a Contested Regional Order: The 'Trilemma' of US–North Korea Relations." Asia Policy 23.1 (2017): 97–103. online

- ISBN 978-1-84668-067-0.

- Lee, Hong Yung. "North Korea in 2013: Economy, Executions, and Nuclear Brinksmanship." Asian Survey 54.1 (2014): 89–100. Online.

- Kirby, Michael; Darusman, Marzuki; Biserko, Sonja (17 February 2014). "Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea". United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Archived from the original on 17 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- Martin, Bradley K. (2004). Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-32322-6.

- ISBN 978-1933633916.

- "North Korea – A Country Study" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies. 2009.

- Ryang, Sonia (2013). "The North Korean Homeland of Koreans in Japan". In Ryang, Sonia (ed.). Koreans in Japan: Critical Voices from the Margin. London: Routledge. pp. 32–54. ISBN 978-1-136-35305-5.

- Yonhap News Agency, ed. (2003). North Korea Handbook. Yonhap T'ongsin. ISBN 978-0-7656-1004-1.

External links

Government websites

- KCNA Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – website of the Korean Central News Agency

- Naenara Archived 18 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine – the official North Korean governmental portal Naenara

- DPRK Foreign Ministry Archived 24 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine – official North Korean foreign ministry website

- The Pyongyang Times – official foreign language newspaper of the DPRK

General websites

- North Korea at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- North Korea at Curlie

- Official website of the DPR of Korea – Administered by the Korean Friendship Association

- 38North

- North Korea profile at BBC News

- North Korea – link collection (University of Colorado at BoulderLibraries GovPubs)

- NKnews – a news agency covering North Korean topics.

- Friend.com.kp Archived 6 November 2015 at archive.today – website of the Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries

- Korea Education Fund