Diabetes

| Diabetes mellitus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Universal blue circle symbol for diabetes[1] | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | |

| Complications | |

| Duration | Remission may occur, but diabetes is often life-long |

| Types |

|

| Causes | Insulin insufficiency or gradual resistance |

| Risk factors | |

| Diagnostic method |

|

| Treatment | |

| Medication | |

| Frequency | 463 million (8.8%)[9] |

| Deaths | 4.2 million (2019)[9] |

Diabetes mellitus, often known simply as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels.[10][11] Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough insulin, or the cells of the body becoming unresponsive to the hormone's effects.[12] Classic symptoms include thirst, polyuria, weight loss, and blurred vision. If left untreated, the disease can lead to various health complications, including disorders of the cardiovascular system, eye, kidney, and nerves.[3] Untreated or poorly treated diabetes accounts for approximately 1.5 million deaths every year.[10]

The major types of diabetes are

As of 2021, an estimated 537 million people had diabetes worldwide accounting for 10.5% of the adult population, with type 2 making up about 90% of all cases. It is estimated that by 2045, approximately 783 million adults, or 1 in 8, will be living with diabetes, representing a 46% increase from the current figures.[13] The prevalence of the disease continues to increase, most dramatically in low- and middle-income nations.[14] Rates are similar in women and men, with diabetes being the seventh leading cause of death globally.[15][16] The global expenditure on diabetes-related healthcare is an estimated US$760 billion a year.[17]

Signs and symptoms

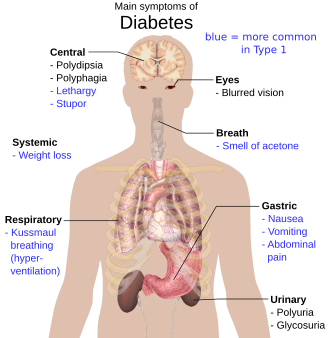

The classic symptoms of untreated diabetes are polyuria, thirst, and weight loss.[18] Several other non-specific signs and symptoms may also occur, including fatigue, blurred vision, and genital itchiness due to Candida infection.[18] About half of affected individuals may also be asymptomatic.[18] Type 1 presents abruptly following a pre-clinical phase, while type 2 has a more insidious onset; patients may remain asymptomatic for many years.[19]

Diabetic ketoacidosis is a medical emergency that occurs most commonly in type 1, but may also occur in type 2 if it has been longstanding or if the individual has significant β-cell dysfunction.[20] Excessive production of ketone bodies leads to signs and symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, the smell of acetone in the breath, deep breathing known as Kussmaul breathing, and in severe cases decreased level of consciousness.[20] Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state is another emergency characterised by dehydration secondary to severe hyperglycaemia, with resultant hypernatremia leading to an altered mental state and possibly coma.[21]

Hypoglycaemia is a recognised complication of insulin treatment used in diabetes.[22] An acute presentation can include mild symptoms such as sweating, trembling, and palpitations, to more serious effects including impaired cognition, confusion, seizures, coma, and rarely death.[22] Recurrent hypoglycaemic episodes may lower the glycaemic threshold at which symptoms occur, meaning mild symptoms may not appear before cognitive deterioration begins to occur.[22]

Long-term complications

The major long-term complications of diabetes relate to damage to

Microvascular disease affects the

Based on extensive data and numerous cases of gallstone disease, it appears that a causal link might exist between type 2 diabetes and gallstones. People with diabetes are at a higher risk of developing gallstones compared to those without diabetes.[29]

There is a link between

Causes

| Feature | Type 1 diabetes | Type 2 diabetes |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Sudden | Gradual |

| Age at onset | Mostly in children | Mostly in adults |

| Body size | Thin or normal[33] | Often obese

|

| Ketoacidosis | Common | Rare |

Autoantibodies

|

Usually present | Absent |

| Endogenous insulin | Low or absent | Normal, decreased or increased |

| Heritability | 0.69 to 0.88[34][35][36] | 0.47 to 0.77[37] |

| Prevalence

(age standardized) |

<2 per 1,000[38] | ~6% (men), ~5% (women)[39] |

Diabetes is classified by the

Type 1

Type 1 accounts for 5 to 10% of diabetes cases and is the most common type diagnosed in patients under 20 years; Type 1 diabetes is partly

Type 1 diabetes can occur at any age, and a significant proportion is diagnosed during adulthood.

Type 2

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by

Type 2 diabetes is primarily due to lifestyle factors and genetics.[53] A number of lifestyle factors are known to be important to the development of type 2 diabetes, including obesity (defined by a body mass index of greater than 30), lack of physical activity, poor diet, stress, and urbanization.[32][54] Excess body fat is associated with 30% of cases in people of Chinese and Japanese descent, 60–80% of cases in those of European and African descent, and 100% of Pima Indians and Pacific Islanders.[12] Even those who are not obese may have a high waist–hip ratio.[12]

Dietary factors such as sugar-sweetened drinks are associated with an increased risk.[55][56] The type of fats in the diet is also important, with saturated fat and trans fats increasing the risk and polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fat decreasing the risk.[53] Eating white rice excessively may increase the risk of diabetes, especially in Chinese and Japanese people.[57] Lack of physical activity may increase the risk of diabetes in some people.[58]

Antipsychotic medication side effects (specifically metabolic abnormalities, dyslipidemia and weight gain) and unhealthy lifestyles (including poor diet and decreased physical activity), are potential risk factors.[60]

Gestational diabetes

Gestational diabetes resembles type 2 diabetes in several respects, involving a combination of relatively inadequate insulin secretion and responsiveness. It occurs in about 2–10% of all pregnancies and may improve or disappear after delivery.[61] It is recommended that all pregnant women get tested starting around 24–28 weeks gestation.[62] It is most often diagnosed in the second or third trimester because of the increase in insulin-antagonist hormone levels that occurs at this time.[62] However, after pregnancy approximately 5–10% of women with gestational diabetes are found to have another form of diabetes, most commonly type 2.[61] Gestational diabetes is fully treatable, but requires careful medical supervision throughout the pregnancy. Management may include dietary changes, blood glucose monitoring, and in some cases, insulin may be required.[63]

Though it may be transient, untreated gestational diabetes can damage the health of the fetus or mother. Risks to the baby include

Other types

Some cases of diabetes are caused by the body's tissue receptors not responding to insulin (even when insulin levels are normal, which is what separates it from type 2 diabetes); this form is very uncommon. Genetic mutations (autosomal or mitochondrial) can lead to defects in beta cell function. Abnormal insulin action may also have been genetically determined in some cases. Any disease that causes extensive damage to the pancreas may lead to diabetes (for example, chronic pancreatitis and cystic fibrosis). Diseases associated with excessive secretion of insulin-antagonistic hormones can cause diabetes (which is typically resolved once the hormone excess is removed). Many drugs impair insulin secretion and some toxins damage pancreatic beta cells, whereas others increase insulin resistance (especially glucocorticoids which can provoke "steroid diabetes"). The ICD-10 (1992) diagnostic entity, malnutrition-related diabetes mellitus (ICD-10 code E12), was deprecated by the World Health Organization (WHO) when the current taxonomy was introduced in 1999.[68] Yet another form of diabetes that people may develop is double diabetes. This is when a type 1 diabetic becomes insulin resistant, the hallmark for type 2 diabetes or has a family history for type 2 diabetes.[69] It was first discovered in 1990 or 1991.

The following is a list of disorders that may increase the risk of diabetes:[70]

- Genetic defects of β-cell function

- Maturity onset diabetes of the young

- Mitochondrial DNA mutations

- Genetic defects in insulin processing or insulin action

- Defects in proinsulin conversion

- Insulin gene mutations

- Insulin receptor mutations

- Exocrine pancreatic defects (see Type 3c diabetes, i.e. pancreatogenic diabetes)

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Pancreatectomy

- Pancreatic neoplasia

- Cystic fibrosis

- Hemochromatosis

- Fibrocalculous pancreatopathy

- Endocrinopathies

- Growth hormone excess (acromegaly)

- Cushing syndrome

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hypothyroidism

- Pheochromocytoma

- Glucagonoma

- Infections

- Cytomegalovirus infection

- Coxsackievirus B

- Drugs

- Glucocorticoids

- Thyroid hormone

- β-adrenergic agonists

- Statins[71]

Pathophysiology

The body obtains glucose from three main sources: the intestinal absorption of food; the breakdown of glycogen (glycogenolysis), the storage form of glucose found in the liver; and gluconeogenesis, the generation of glucose from non-carbohydrate substrates in the body.[73] Insulin plays a critical role in regulating glucose levels in the body. Insulin can inhibit the breakdown of glycogen or the process of gluconeogenesis, it can stimulate the transport of glucose into fat and muscle cells, and it can stimulate the storage of glucose in the form of glycogen.[73]

Insulin is released into the blood by beta cells (β-cells), found in the

If the amount of insulin available is insufficient, or if cells respond poorly to the effects of insulin (insulin resistance), or if the insulin itself is defective, then glucose is not absorbed properly by the body cells that require it, and is not stored appropriately in the liver and muscles. The net effect is persistently high levels of blood glucose, poor protein synthesis, and other metabolic derangements, such as metabolic acidosis in cases of complete insulin deficiency.[73]

When there is too much glucose in the blood for a long time, the

Diagnosis

Diabetes mellitus is diagnosed with a test for the glucose content in the blood, and is diagnosed by demonstrating any one of the following:[68]

- Fasting plasma glucose level≥ 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL). For this test, blood is taken after a period of fasting, i.e. in the morning before breakfast, after the patient had sufficient time to fast overnight or at least 8 hours before the test.

- Plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) two hours after a 75 gram oral glucose load as in a glucose tolerance test(OGTT)

- Symptoms of high blood sugar and plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) either while fasting or not fasting

- DCCT %).[77]

| Condition | 2-hour glucose | Fasting glucose | HbA1c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | mmol/L | mg/dL | mmol/L | mg/dL | mmol/mol | DCCT % |

| Normal | < 7.8 | < 140 | < 6.1 | < 110 | < 42 | < 6.0 |

Impaired fasting glycaemia |

< 7.8 | < 140 | 6.1–7.0 | 110–125 | 42–46 | 6.0–6.4 |

Impaired glucose tolerance |

≥ 7.8 | ≥ 140 | < 7.0 | < 126 | 42–46 | 6.0–6.4 |

Diabetes mellitus |

≥ 11.1 | ≥ 200 | ≥ 7.0 | ≥ 126 | ≥ 48 | ≥ 6.5 |

A positive result, in the absence of unequivocal high blood sugar, should be confirmed by a repeat of any of the above methods on a different day. It is preferable to measure a fasting glucose level because of the ease of measurement and the considerable time commitment of formal glucose tolerance testing, which takes two hours to complete and offers no prognostic advantage over the fasting test.[80] According to the current definition, two fasting glucose measurements at or above 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) is considered diagnostic for diabetes mellitus.

Per the WHO, people with fasting glucose levels from 6.1 to 6.9 mmol/L (110 to 125 mg/dL) are considered to have

Prevention

There is no known

The relationship between type 2 diabetes and the main modifiable risk factors (excess weight, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and tobacco use) is similar in all regions of the world. There is growing evidence that the underlying determinants of diabetes are a reflection of the major forces driving social, economic and cultural change: globalization, urbanization, population aging, and the general health policy environment.[90]

Management

Diabetes management concentrates on keeping blood sugar levels close to normal, without causing low blood sugar.[91] This can usually be accomplished with dietary changes,[92] exercise, weight loss, and use of appropriate medications (insulin, oral medications).[91]

Learning about the disease and actively participating in the treatment is important, since complications are far less common and less severe in people who have well-managed blood sugar levels.[91][93] The goal of treatment is an A1C level below 7%.[94][95] Attention is also paid to other health problems that may accelerate the negative effects of diabetes. These include smoking, high blood pressure, metabolic syndrome obesity, and lack of regular exercise.[91][96] Specialized footwear is widely used to reduce the risk of diabetic foot ulcers by relieving the pressure on the foot.[97][98][99] Foot examination for patients living with diabetes should be done annually which includes sensation testing, foot biomechanics, vascular integrity and foot structure.[100]

Concerning those with severe mental illness, the efficacy of type 2 diabetes self-management interventions is still poorly explored, with insufficient scientific evidence to show whether these interventions have similar results to those observed in the general population.[101]

Lifestyle

People with diabetes can benefit from education about the disease and treatment, dietary changes, and exercise, with the goal of keeping both short-term and long-term blood glucose levels within acceptable bounds. In addition, given the associated higher risks of cardiovascular disease, lifestyle modifications are recommended to control blood pressure.[102][103]

A 2020 Cochrane systematic review compared several non-nutritive sweeteners to sugar, placebo and a nutritive low-calorie sweetener (tagatose), but the results were unclear for effects on HbA1c, body weight and adverse events.[108] The studies included were mainly of very low-certainty and did not report on health-related quality of life, diabetes complications, all-cause mortality or socioeconomic effects.[108]

Medications

Glucose control

Most medications used to treat diabetes act by lowering

There are a number of different classes of anti-diabetic medications. Type 1 diabetes requires treatment with

Metformin is generally recommended as a first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes, as there is good evidence that it decreases mortality.[7] It works by decreasing the liver's production of glucose, and increasing the amount of glucose stored in peripheral tissue.[114] Several other groups of drugs, mainly oral medication, may also decrease blood sugar in type 2 diabetes. These include agents that increase insulin release (sulfonylureas), agents that decrease absorption of sugar from the intestines (acarbose), agents that inhibit the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) that inactivates incretins such as GLP-1 and GIP (sitagliptin), agents that make the body more sensitive to insulin (thiazolidinedione) and agents that increase the excretion of glucose in the urine (SGLT2 inhibitors).[114] When insulin is used in type 2 diabetes, a long-acting formulation is usually added initially, while continuing oral medications.[7]

Some severe cases of type 2 diabetes may also be treated with insulin, which is increased gradually until glucose targets are reached.[7][115]

Blood pressure lowering

Cardiovascular disease is a serious complication associated with diabetes, and many international guidelines recommend blood pressure treatment targets that are lower than 140/90 mmHg for people with diabetes.[116] However, there is only limited evidence regarding what the lower targets should be. A 2016 systematic review found potential harm to treating to targets lower than 140 mmHg,[117] and a subsequent systematic review in 2019 found no evidence of additional benefit from blood pressure lowering to between 130 – 140mmHg, although there was an increased risk of adverse events.[118]

2015 American Diabetes Association recommendations are that people with diabetes and albuminuria should receive an inhibitor of the renin-angiotensin system to reduce the risks of progression to end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular events, and death.

Aspirin

The use of aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease in diabetes is controversial.[119] Aspirin is recommended by some in people at high risk of cardiovascular disease, however routine use of aspirin has not been found to improve outcomes in uncomplicated diabetes.[123] 2015 American Diabetes Association recommendations for aspirin use (based on expert consensus or clinical experience) are that low-dose aspirin use is reasonable in adults with diabetes who are at intermediate risk of cardiovascular disease (10-year cardiovascular disease risk, 5–10%).[119] National guidelines for England and Wales by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend against the use of aspirin in people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who do not have confirmed cardiovascular disease.[112][113]

Surgery

Weight loss surgery in those with obesity and type 2 diabetes is often an effective measure.[124] Many are able to maintain normal blood sugar levels with little or no medications following surgery[125] and long-term mortality is decreased.[126] There is, however, a short-term mortality risk of less than 1% from the surgery.[127] The body mass index cutoffs for when surgery is appropriate are not yet clear.[126] It is recommended that this option be considered in those who are unable to get both their weight and blood sugar under control.[128]

A

Self-management and support

In countries using a general practitioner system, such as the United Kingdom, care may take place mainly outside hospitals, with hospital-based specialist care used only in case of complications, difficult blood sugar control, or research projects. In other circumstances, general practitioners and specialists share care in a team approach. Evidence has shown that social prescribing led to slight improvements in blood sugar control for people with type 2 diabetes.[130] Home telehealth support can be an effective management technique.[131]

The use of technology to deliver educational programs for adults with type 2 diabetes includes computer-based self-management interventions to collect for tailored responses to facilitate self-management.[132] There is no adequate evidence to support effects on cholesterol, blood pressure, behavioral change (such as physical activity levels and dietary), depression, weight and health-related quality of life, nor in other biological, cognitive or emotional outcomes.[132][133]

Epidemiology

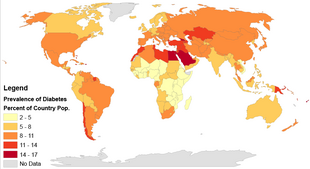

In 2017, 425 million people had diabetes worldwide,[134] up from an estimated 382 million people in 2013[135] and from 108 million in 1980.[136] Accounting for the shifting age structure of the global population, the prevalence of diabetes is 8.8% among adults, nearly double the rate of 4.7% in 1980.[134][136] Type 2 makes up about 90% of the cases.[15][32] Some data indicate rates are roughly equal in women and men,[15] but male excess in diabetes has been found in many populations with higher type 2 incidence, possibly due to sex-related differences in insulin sensitivity, consequences of obesity and regional body fat deposition, and other contributing factors such as high blood pressure, tobacco smoking, and alcohol intake.[137][138]

The WHO estimates that diabetes resulted in 1.5 million deaths in 2012, making it the 8th leading cause of death.[139][136] However another 2.2 million deaths worldwide were attributable to high blood glucose and the increased risks of cardiovascular disease and other associated complications (e.g. kidney failure), which often lead to premature death and are often listed as the underlying cause on death certificates rather than diabetes.[136][140] For example, in 2017, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimated that diabetes resulted in 4.0 million deaths worldwide,[134] using modeling to estimate the total number of deaths that could be directly or indirectly attributed to diabetes.[134]

Diabetes occurs throughout the world but is more common (especially type 2) in more developed countries. The greatest increase in rates has however been seen in low- and middle-income countries,[136] where more than 80% of diabetic deaths occur.[141] The fastest prevalence increase is expected to occur in Asia and Africa, where most people with diabetes will probably live in 2030.[142] The increase in rates in developing countries follows the trend of urbanization and lifestyle changes, including increasingly sedentary lifestyles, less physically demanding work and the global nutrition transition, marked by increased intake of foods that are high energy-dense but nutrient-poor (often high in sugar and saturated fats, sometimes referred to as the "Western-style" diet).[136][142] The global number of diabetes cases might increase by 48% between 2017 and 2045.[134]

As of 2020, 38% of all US adults had prediabetes.[143] Prediabetes is an early stage of diabetes.

History

Diabetes was one of the first diseases described,

The term "diabetes" or "to pass through" was first used in 230 BCE by the Greek

The earliest surviving work with a detailed reference to diabetes is that of

Two types of diabetes were identified as separate conditions for the first time by the Indian physicians Sushruta and Charaka in 400–500 CE with one type being associated with youth and another type with being overweight.[145] Effective treatment was not developed until the early part of the 20th century when Canadians Frederick Banting and Charles Best isolated and purified insulin in 1921 and 1922.[145] This was followed by the development of the long-acting insulin NPH in the 1940s.[145]

Etymology

The word diabetes (/ˌdaɪ.əˈbiːtiːz/ or /ˌdaɪ.əˈbiːtɪs/) comes from Latin diabētēs, which in turn comes from Ancient Greek διαβήτης (diabētēs), which literally means "a passer through; a siphon".[148] Ancient Greek physician Aretaeus of Cappadocia (fl. 1st century CE) used that word, with the intended meaning "excessive discharge of urine", as the name for the disease.[149][150] Ultimately, the word comes from Greek διαβαίνειν (diabainein), meaning "to pass through",[148] which is composed of δια- (dia-), meaning "through" and βαίνειν (bainein), meaning "to go".[149] The word "diabetes" is first recorded in English, in the form diabete, in a medical text written around 1425.

The word

Society and culture

The 1989 "St. Vincent Declaration"[154][155] was the result of international efforts to improve the care accorded to those with diabetes. Doing so is important not only in terms of quality of life and life expectancy but also economically – expenses due to diabetes have been shown to be a major drain on health – and productivity-related resources for healthcare systems and governments.

Several countries established more and less successful national diabetes programmes to improve treatment of the disease.[156]

Diabetes stigma

Diabetes stigma describes the negative attitudes, judgment, discrimination, or prejudice against people with diabetes. Often, the stigma stems from the idea that diabetes (particularly Type 2 diabetes) resulted from poor lifestyle and unhealthy food choices rather than other causal factors like genetics and social determinants of health.[157] Manifestation of stigma can be seen throughout different cultures and contexts. Scenarios include diabetes statuses affecting marriage proposals, workplace-employment, and social standing in communities.[158]

Stigma is also seen internally, as people with diabetes can also have negative beliefs about themselves. Often these cases of self-stigma are associated with higher diabetes-specific distress, lower self-efficacy, and poorer provider-patient interactions during diabetes care.[159]

Racial and economic inequalities

Racial and ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected with higher prevalence of diabetes compared to non-minority individuals.[160] While US adults overall have a 40% chance of developing type 2 diabetes, Hispanic/Latino adults chance is more than 50%.[161] African Americans also are much more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes compared to White Americans. Asians have increased risk of diabetes as diabetes can develop at lower BMI due to differences in visceral fat compared to other races. For Asians, diabetes can develop at a younger age and lower body fat compared to other groups. Additionally, diabetes is highly underreported in Asian American people, as 1 in 3 cases are diagnosed compared to the average 1 in 5 for the nation.[162]

People with diabetes who have neuropathic symptoms such as numbness or tingling in feet or hands are twice as likely to be

In 2010, diabetes-related emergency room (ER) visit rates in the United States were higher among people from the lowest income communities (526 per 10,000 population) than from the highest income communities (236 per 10,000 population). Approximately 9.4% of diabetes-related ER visits were for the uninsured.[164]

Naming

The term "type 1 diabetes" has replaced several former terms, including childhood-onset diabetes, juvenile diabetes, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Likewise, the term "type 2 diabetes" has replaced several former terms, including adult-onset diabetes, obesity-related diabetes, and noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Beyond these two types, there is no agreed-upon standard nomenclature.[165]

Diabetes mellitus is also occasionally known as "sugar diabetes" to differentiate it from diabetes insipidus.[166]

Other animals

Diabetes can occur in mammals or reptiles.[167][168] Birds do not develop diabetes because of their unusually high tolerance for elevated blood glucose levels.[169]

In animals, diabetes is most commonly encountered in dogs and cats. Middle-aged animals are most commonly affected. Female dogs are twice as likely to be affected as males, while according to some sources, male cats are more prone than females. In both species, all breeds may be affected, but some small dog breeds are particularly likely to develop diabetes, such as Miniature Poodles.[170]

Feline diabetes is strikingly similar to human type 2 diabetes. The Burmese, Russian Blue, Abyssinian, and Norwegian Forest cat breeds are at higher risk than other breeds. Overweight cats are also at higher risk.[171]

The symptoms may relate to fluid loss and polyuria, but the course may also be insidious. Diabetic animals are more prone to infections. The long-term complications recognized in humans are much rarer in animals. The principles of treatment (weight loss, oral antidiabetics, subcutaneous insulin) and management of emergencies (e.g. ketoacidosis) are similar to those in humans.[170]

See also

References

- ^ "Diabetes Blue Circle Symbol". International Diabetes Federation. 17 March 2006. Archived from the original on 5 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Diabetes". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ from the original on 2016-06-25.

- PMID 29934758.

- PMID 27660698.

- ^ a b "Causes of Diabetes - NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. June 2014. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2013-05-05.

- ^ Brutsaert EF (February 2017). "Drug Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus". MSDManuals.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b "IDF DIABETES ATLAS Ninth Edition 2019" (PDF). www.diabetesatlas.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Diabetes". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ "Diabetes Mellitus (DM) - Hormonal and Metabolic Disorders". MSD Manual Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-162243-1.

- ^ "Facts & figures". International Diabetes Federation. Archived from the original on 2023-08-10. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- PMID 29665834.

- ^ PMID 23245607.

- ^ "The top 10 causes of death". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- S2CID 3538441.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7020-7868-2.

- ISBN 978-0-323-53266-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7020-8348-8.

- from the original on 2023-08-10. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ PMID 33550443.

- ^ a b "Diabetes - long-term effects". Better Health Channel. Victoria: Department of Health. Archived from the original on 2023-10-29. Retrieved 2023-08-12.

- PMID 20609967.

- PMID 23247304.

- PMID 29713648.

- ^ "Diabetes eye care". MedlinePlus. Maryland: National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2018-03-28. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-72271-1.

- PMID 33418132.

- PMID 16283246.

- PMID 27515679.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4377-0324-5.

- .

- PMID 32229696.

- PMID 12663480.

- (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-01. Retrieved 2021-12-27.

- S2CID 17854531.

- PMID 32901098.

- PMID 34399949.

- ISBN 978-92-4-151570-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-03-06. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- S2CID 12679248.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-60992-0.

- PMID 17429082.

- ^ Brutsaert, EF (September 2022). "Diabetes Mellitus (DM)". MSD Manual Professional Version. Merck Publishing. Archived from the original on 2023-08-15. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- ^ PMID 26280364.

So far, none of the hypotheses accounting for virus-induced beta cell autoimmunity has been supported by stringent evidence in humans, and the involvement of several mechanisms rather than just one is also plausible.

- PMID 27545597.

- PMID 25601320.

- ^ "What Is Diabetes?". Diabetes Daily. Archived from the original on 2023-10-04. Retrieved 2023-09-10.

- PMID 37120620.

- from the original on 2024-02-07, retrieved 2024-02-13

- PMID 27979889.

- PMID 30528418.

- ^ PMID 19032965.

- from the original on 2023-10-20. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- PMID 20308626.

- PMID 20693348.

- PMID 22422870.

- PMID 22818936.

- PMID 26404480.

- PMID 29162032.

- ^ a b "National Diabetes Clearinghouse (NDIC): National Diabetes Statistics 2011". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ S2CID 209272489.

- ^ "Managing & Treating Gestational Diabetes | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 2019-05-06. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- S2CID 235487220.

- ^ National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health (February 2015). "Intrapartum care". Diabetes in Pregnancy: Management of diabetes and its complications from preconception to the postnatal period. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

- ^ "Monogenic Forms of Diabetes". National institute of diabetes and digestive and kidney diseases. US NIH. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- S2CID 44891167.

- ^ a b "Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications" (PDF). World Health Organization. 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2003-03-08.

- PMID 23613085.

- ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- S2CID 11544414.

- ^ "Insulin Basics". American Diabetes Association. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-162243-1.

- ISBN 978-0-07-178003-2.

- ISBN 978-0-07-176576-3.

- ^ Mogotlane S (2013). Juta's Complete Textbook of Medical Surgical Nursing. Cape Town: Juta. p. 839.

- from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ISBN 978-92-4-159493-6.

- PMID 20194231.

- PMID 11473076.

- ISBN 978-92-4-159493-6. Archived(PDF) from the original on 11 May 2012.

- from the original on 16 September 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- PMID 21238885.

- PMID 20200384.

- PMID 29559955.

- PMID 33388268.

- PMID 27510511.

- ^ a b "Simple Steps to Preventing Diabetes". The Nutrition Source. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. 18 September 2012. Archived from the original on 25 April 2014.

- S2CID 30550981.

- ^ "Chronic diseases and their common risk factors" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-17. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Managing diabetes". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, US National Institutes of Health. 1 December 2016. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- PMID 30487971.

- S2CID 24754081.

- ^ "The A1C test and diabetes". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, US National Institutes of Health. 1 April 2018. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- PMID 29507945.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 66: Type 2 diabetes. London, 2008.

- S2CID 24862853.

- S2CID 12012686.

- (PDF) from the original on 2023-02-09. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

- PMID 14693928.

- PMID 27120555.

- PMID 29114778.

- PMID 28836234.

- ^ PMID 30559231.

- ^ PMID 31000505.

- ^ PMID 26411958.

- S2CID 207474124.

- ^ PMID 32449201.

- PMID 24286948.

- PMID 29580578.

- PMID 24843750.

- ^ a b "Type 1 diabetes in adults: diagnosis and management". www.nice.org.uk. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Type 2 diabetes in adults: management". www.nice.org.uk. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2 December 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ S2CID 29670619.

- ^ Consumer Reports; American College of Physicians (April 2012), "Choosing a type 2 diabetes drug – Why the best first choice is often the oldest drug" (PDF), High Value Care, Consumer Reports, archived (PDF) from the original on July 2, 2014, retrieved August 14, 2012

- PMID 31451236.

- PMID 26920333.

- PMID 31575567.

- ^ PMID 26246459.

- PMID 24687000.

- PMID 28844155.

- ^ PMID 26954482.

- PMID 20508233.

- PMID 19726018.

- S2CID 31797748.

- ^ PMID 19625245.

- S2CID 207551737.

- S2CID 5198462.

- ^ "Pancreas Transplantation". American Diabetes Association. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- S2CID 44260857.

- ^ PMID 23543567.

- PMID 22161430.

- ^ a b c d e Elflein J (10 December 2019). Estimated number diabetics worldwide. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- S2CID 7496891.

- ^ a b c d e f "Global Report on Diabetes" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- PMID 11206408.

- PMID 11784224.

- ^ "The top 10 causes of death Fact sheet N°310". World Health Organization. October 2013. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017.

- ^ Public Health Agency of Canada, Diabetes in Canada: Facts and figures from a public health perspective. Ottawa, 2011.

- PMID 17132052.

- ^ PMID 15111519.

- ^ "Prevalence of Prediabetes Among Adults - Diabetes". CDC. 2018-03-13. Archived from the original on 2023-03-06. Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- ISBN 978-1-4398-2759-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-03.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-387-09840-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-04.

- ^ a b Roberts J (2015). "Sickening sweet". Distillations. Vol. 1, no. 4. pp. 12–15. Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2017-01-04.

- ^ a b Oxford English Dictionary. diabetes. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ a b Harper D (2001–2010). "Online Etymology Dictionary. diabetes.". Archived from the original on 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ Aretaeus, De causis et signis acutorum morborum (lib. 2), Κεφ. β. περὶ Διαβήτεω (Chapter 2, On Diabetes, Greek original) Archived 2014-07-02 at the Wayback Machine, on Perseus

- ^ a b c d Oxford English Dictionary. mellite. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ a b c d "MyEtimology. mellitus.". Archived from the original on 2011-03-16. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Oxford English Dictionary. -ite. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ISBN 978-0-12-370890-8.

- S2CID 9931183.

- ^ Dubois H, Bankauskaite V (2005). "Type 2 diabetes programmes in Europe" (PDF). Euro Observer. 7 (2): 5–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-24.

- ^ CDC (2022-11-03). "Diabetes Stigma: Learn About It, Recognize It, Reduce It". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2023-10-31. Retrieved 2023-10-31.

- S2CID 207490680.

- S2CID 221366068.

- PMID 24037313.

- ^ CDC (2022-04-04). "Hispanic/Latino Americans and Type 2 Diabetes". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2023-10-31. Retrieved 2023-10-31.

- ^ CDC (2022-11-21). "Diabetes and Asian American People". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2023-10-31. Retrieved 2023-10-31.

- S2CID 21487348.

- from the original on 2013-12-03.

- ^ "Type 1 vs. Type 2 Diabetes Differences: Which One Is Worse?". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2021-03-21.

- ISBN 978-1-4381-2108-6.

- PMID 29805204.

- ISBN 978-0-7216-9327-9.

- S2CID 250404382.

- ^ a b "Diabetes mellitus". Merck Veterinary Manual (9th ed.). 2005. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ISBN 978-91-7760-067-1. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2021-04-13. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

External links

- American Diabetes Association

- IDF Diabetes Atlas

- National Diabetes Education Program

- ADA's Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2019

- Polonsky KS (October 2012). "The past 200 years in diabetes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (14): 1332–1340. S2CID 9456681.

- "Diabetes". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.