Dicynodont

| Dicynodonts Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of Diictodon | |

| |

| Skeleton of Placerias | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Anomodontia |

| Clade: | †Chainosauria |

| Clade: | †Dicynodontia Owen, 1859 |

| Clades & genera | |

|

see "Taxonomy" | |

Dicynodontia is an extinct

Characteristics

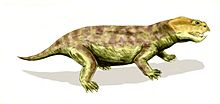

The dicynodont

The body is short, strong and barrel-shaped, with strong limbs. In large genera (such as

Pentasauropus dicynodont tracks suggest that dicynodonts had fleshy pads on their feet.[7] Mummified skin from specimens of Lystrosaurus in South Africa have numerous raised bumps.[8]

Endothermy and soft tissue anatomy

Dicynodonts have long been suspected of being warm-blooded animals. Their bones are highly vascularised and possess Haversian canals, and their bodily proportions are conducive to heat preservation.[9] In young specimens, the bones are so highly vascularised that they exhibit higher channel densities than most other therapsids.[10] Yet, studies on Late Triassic dicynodont coprolites paradoxically showcase digestive patterns more typical of animals with slow metabolisms.[11]

More recently, the discovery of hair remnants in Permian coprolites possibly vindicates the status of dicynodonts as endothermic animals. As these coprolites come from carnivorous species and digested dicynodont bones are abundant, it has been suggested that at least some of these hair remnants come from dicynodont prey.[12] A new study using chemical analysis seemed to suggest that cynodonts and dicynodonts both developed warm blood independently before the Permian extinction.[13]

History

Dicynodonts have been known since the mid-1800s. The South African geologist

Evolutionary history

Dicynodonts first appeared during the Middle Permian in the Southern Hemisphere, with South Africa being the centre of their known diversity, and underwent a rapid evolutionary radiation, becoming globally distributed and amongst the most successful and abundant land vertebrates during the Late Permian.[18][19] During this time, they included a large variety of ecotypes, including large, medium-sized, and small herbivores and short-limbed mole-like burrowers.[20]

Only four lineages are known to have survived the Great Dying; the first three represented with a single genus each: Myosaurus, Kombuisia, and Lystrosaurus, the latter being the most common and widespread herbivores of the Induan (earliest Triassic). None of these survived long into the Triassic. The fourth group was the Kannemeyeriiformes, the only dicynodonts who diversified during the Triassic.[21] These stocky, pig- to ox-sized animals were the most abundant herbivores worldwide from the Olenekian to the Ladinian age. By the Carnian they had been supplanted by traversodont cynodonts and rhynchosaur reptiles. During the Norian (middle of the Late Triassic), perhaps due to increasing aridity, they drastically declined, and the role of large herbivores was taken over by sauropodomorph dinosaurs.[citation needed]

Fossils of an Asian elephant-sized dicynodont Lisowicia bojani discovered in Poland indicate that dicynodonts survived at least until the late Norian or earliest Rhaetian (latest Triassic); this animal was also the largest known dicynodont species.[22][23]

Six fragments of fossil bone discovered in Queensland, Australia, were interpreted as remains of a skull in 2003. This suggested to indicate that dicynodonts survived into the Cretaceous in southern Gondwana.[24] The dicynodont affinity of these specimens was questioned (including a proposal that they belonged to a baurusuchian crocodyliform by Agnolin et al. in 2010),[25] and in 2019 Knutsen and Oerlemans considered this fossil to be of Plio-Pleistocene age, and reinterpreted it as a fossil of a large mammal, probably a diprotodontid.[26]

With the decline and extinction of the kannemeyerids, there were to be no more dominant large synapsid herbivores until the middle Paleocene epoch (60 Ma) when mammals, distant descendants of cynodonts, began to diversify after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs.

Systematics

Taxonomy

Dicynodontia was originally named by the English paleontologist

Many higher taxa, including infraorders and families, have been erected as a means of classifying the large number of dicynodont species. Cluver and King (1983) recognised several main groups within Dicynodontia, including Eodicynodontia (containing only

Current classification

- Dicynodontia

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram modified from Angielczyk et al. (2021):[30]

| Dicynodontia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- S2CID 91926999.

- ^ Crompton, A. W.; Hotton, N. (1967). "Functional morphology of the masticatory apparatus of two dicynodonts (Reptilia, Therapsida)". Postilla. 109: 1–51.

- S2CID 239890042.

- S2CID 210304700.

- S2CID 233565963.

- ^ Colbert, E. H., (1969), Evolution of the Vertebrates, John Wiley & Sons Inc (2nd ed.)

- PMID 30123702.

- S2CID 251781291.

- .

- .

- .

- .

- PMID 28716184.

- S2CID 128602890.

- ^ a b Owen, R. (1876). Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the Collection of the British Museum. London: British Museum. p. 88.

- ^ Owen, R. (1860). "On the orders of fossil and recent Reptilia, and their distribution in time". Report of the Twenty-Ninth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. 1859: 153–166.

- ^ a b Kammerer, C.F.; Angielczyk, K.D. (2009). "A proposed higher taxonomy of anomodont therapsids" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2018: 1–24.

- S2CID 129331000.

- ISSN 0012-8252.

- S2CID 92370138.

- PMID 23741307.

- PMID 30467179.

- ^ St. Fleur, Nicholas (4 January 2019). "An Elephant-Size Relative of Mammals That Grazed Alongside Dinosaurs". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- PMID 12803915.

- S2CID 130568551.

- S2CID 202908716.

- S2CID 84492986.

- S2CID 131459807.

- ^ Cluver, M.A.; King, G.M. (1983). "A reassessment of the relationships of Permian Dicynodontia (Reptilia, Therapsida) and a new classification of dicynodont". Annals of the South African Museum. 91: 195–273.

- S2CID 236406006.

Further reading

- Carroll, R. L. (1988), Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, WH Freeman & Co.

- Cox, B., Savage, R.J.G., Gardiner, B., Harrison, C. and Palmer, D. (1988) The Marshall illustrated encyclopedia of dinosaurs & prehistoric animals, 2nd Edition, Marshall Publishing

- King, Gillian M., "Anomodontia" Part 17 C, Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology, Gutsav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart and New York, 1988

- King, Gillian M., 1990, The Dicynodonts: A Study in Palaeobiology, Chapman and Hall, London and New York