Excavata

| Excavata Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

Giardia lamblia , a parasitic diplomonad

| |

| Scientific classification (obsolete as paraphyletic) | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| (unranked): | Excavata (Cavalier-Smith), 2002 |

| Phyla and classes | |

|

see text | |

Excavata is an extensive and diverse but

On the basis of phylogenomic analyses, the group was shown to contain three widely separated eukaryote groups, the discobids, metamonads, and malawimonads.[8][9][10][11] A current view of the composition of the excavates is given below, indicating that the group is paraphyletic. Except for some Euglenozoa, all are non-photosynthetic.

Characteristics

Most excavates are unicellular, heterotrophic flagellates. Only some

The

Proposed group

Excavate relationships were always uncertain, suggesting that they are not a

Excavates were thought to include multiple groups:

| Kingdom/Superphylum | Included taxa | Representative genera (examples) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discoba or JEH or Eozoa | Tsukubea |

Tsukubamonas |

|

| Euglenozoa | Euglena, Trypanosoma | Many important parasites, one large group with plastids (chloroplasts) | |

Heterolobosea (Percolozoa) |

Acrasis |

Most alternate between flagellate and amoeboid forms

| |

Jakobea |

Jakoba, Reclinomonas | Free-living, sometimes loricate flagellates, with very gene-rich mitochondrial genomes | |

Metamonada or POD |

Preaxostyla |

Oxymonads, Trimastix |

Amitochondriate flagellates, either free-living (Trimastix , Paratrimastix) or living in the hindguts of insects

|

Fornicata |

Giardia, Carpediemonas | Amitochondriate, mostly symbiotes and parasites of animals. | |

Parabasalia |

Trichomonas | Amitochondriate flagellates, generally intestinal commensals of insects. Some human pathogens. | |

| Anaeramoeba | Anaeramoeba ignava | Anaerobic protists with hydrogenosomes instead of mitochondria. | |

Neolouka

|

Malawimonadida | Malawimonas |

Discoba or JEH clade

Euglenozoa and Heterolobosea (Percolozoa) or Eozoa (as named by Cavalier-Smith

Metamonads

Metamonads are unusual in not having classical mitochondria—instead they have hydrogenosomes, mitosomes or uncharacterised organelles. The oxymonad Monocercomonoides is reported to have completely lost homologous organelles. There are competing explanations.[16][17]

Malawimonads

The malawimonads have been proposed to be members of Excavata owing to their typical excavate morphology, and phylogenetic affinity to other excavate groups in some molecular phylogenies. However, their position among eukaryotes remains elusive.[2]

Ancyromonads

Ancyromonads are small free-living cells with a narrow longitudinal groove down one side of the cell. The ancyromonad groove is not used for "suspension feeding", unlike in "typical excavates" (e.g. malawimonads, jakobids, Trimastix, Carpediemonas, Kiperferlia, etc). Ancyromonads instead capture prokaryotes attached to surfaces. The phylogenetic placement of ancyromonads is poorly understood (in 2020), however some phylogenetic analyses place them as close relatives of malawimonads.[9]

Evolution

Origin of the Eukaryotes

The conventional explanation for the origin of the Eukaryotes is that a

Caesar al Jewari and Sandra Baldauf argue instead that the Eukaryotes possibly started with an endosymbiosis event of a

Phylogeny

In 2023, using molecular phylogenetic analysis of 186 taxa, Al Jewari and Baldauf proposed a phylogenetic tree with the metamonad Parabasalia as basal Eukaryotes. Discoba and the rest of the Eukaryota appear to have emerged as

|

"Excavata" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Anaeramoeba are associated with Parabasalia, but could turn out to be more basal as the root of a tree is often difficult to pinpoint.[20]

See also

Gallery

-

Euglenoida)

-

Trypanosoma brucei (Euglenozoa: Kinetoplastida)

-

Bodosp. (Euglenozoa: Kinetoplastida)

-

Percolomonas sp. (Percolozoa)

-

Stephanopogon sp. (Percolozoa)

-

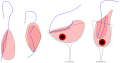

Stages ofHeterolobosea)

-

Acrasis rosea (Percolozoa: Heterolobosea)

-

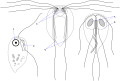

Jakobids (Jakobida)

-

Parabasalia)

-

Retortamonadida)

-

Diplomonadida)

References

- ^ PMID 19237557.

- ^ PMID 16308337.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 14657103.

- ^ ISBN 978-0544859937.

- ^ PMID 11931142.

- PMID 23312067.

- S2CID 204545629.

- ^ PMID 29360967.

- PMID 29765641.

- PMID 31430481.

- Wikidata Q21090155.

- PMID 34358228.

- PMID 20031978.

- PMID 17689961.

- PMID 8790385.

- ^ PMID 37115919.

- PMID 33739376.

- ^ PMID 37316666.

- S2CID 240054026.