Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (

The territory of the Romanian region Dobrogea is organised as the counties of Constanța and Tulcea, with a combined area of 15,588 km2 (6,019 sq mi) and a population of slightly less than 900,000. Its main cities are Constanța, Tulcea, Medgidia and Mangalia. Dobrogea is represented by dolphins in the coat of arms of Romania.

The Bulgarian region Dobrudzha is divided among the administrative regions of Dobrich and Silistra; the following villages of Razgrad Province: Konevo, Rainino, Terter and Madrevo; and the village General Kantardzhievo (Varna). This section has a total area of 7,566 km2 (2,921 sq mi), with a combined population of some 310,000 people, the main towns being Dobrich and Silistra (regional seats).

Geography

Except for the

Dobruja lies in the temperate

Dobruja is a windy region once known for its windmills. There is wind during about 85–90% of all days; it usually comes from the north or northeast. The average wind speed is about twice higher than the average in Bulgaria. Due to the limited precipitation and the proximity to the sea, rivers in Dobruja are usually short and with low discharge. The region has several shallow seaside lakes with brackish water.[2]

Etymology

The most widespread opinion among scholars is that the origin of the term Dobruja is to be found in the Turkish rendition of the name of a 14th‑century Bulgarian ruler,

A version matching contemporaneous descriptions was suggested by

One of the earliest documented uses of the name can be found in the

Initially, the name meant just the steppe of the southern region, between the forests around

History

Prehistory

The territory of Dobruja has been inhabited by humans since

Mikra Skythia

Ancient history

During the early

In 657/656 BC

In 514/512 BC King

In 313 BC and again in 310–309 BC, the Greek colonies led by Callatis, supported by

Early Greek scholars such as

Around 100 BC King

Roman rule

In 28/29 BC

In 15 AD the Roman province of

In the winter of 101–102 the Dacian king

In 118

During the reign of

Byzantine rule

After the division of the

First Bulgarian Empire rule

The results of archaeological research indicate that the Byzantine presence on Dobruja's mainland and the banks of the Danube were reduced at the end of the 6th century, under the pressure of the Migration Period. In the coastal fortifications on the southern bank of the Danube, the latest Byzantine coin found dates from the time of the emperors Tiberius II Constantine (574–582) and Heraclius (610–641). After that period, all inland Byzantine cities were demolished by the invaders and abandoned.[30]

Some of the

According to the peace treaty of 681, signed after the Bulgarian victory over Byzantines in the

According to Bulgarian historians, during the 7th–10th centuries, the region was fortified by construction of a large network of earthen and wooden strongholds and ramparts.[37] Around the end of the 8th century, widespread building of new stone fortresses and defensive walls began.[38] Romanian historians dispute attributing these walls to the Bulgarians, based on their interpretation of the construction system and archaeological evidence.[citation needed] The Bulgarians also reconstructed some of the ruined Byzantine fortresses (Kaliakra and Silistra in the 8th century, Madara and Varna in the 9th).[39] According to Barnea, among other historians, during the following three centuries of Bulgarian domination, Byzantines still controlled the Black Sea coast and the mouths of Danube, and for short periods, even some cities.[40] But Bulgarian archaeologists note that the last Byzantine coins found, which are considered a proof of Byzantine presence, date in Kaliakra from the time of Emperor Justin II (565–578),[41] in Varna from the time of Emperor Heraclius (610–641),[42] and in Tomis from Constantine IV's rule (668–685).[43]

At the beginning of the 8th century,

Return of Byzantine rule and late migrations

With financial encouragement from the Byzantine emperor,

According to some historians, soon after 976

To prevent mounted attacks from the north, the Byzantines constructed three ramparts from the Black Sea down to the Danube, in the 10th–11th centuries.[54][55] According to Bulgarian archaeologists and historians, these fortifications may have been built much earlier and were erected by the First Bulgarian Empire in response to the threat of Khazars' raids.[56][57]

From the 10th century, Byzantines accepted small groups of

In 1064, an invasion by the Oghuz Turks affected the region. During 1072 to 1074, when Nestor (the new strategos of Paristrion) was in Dristra, he found that the Pecheneg ruler, Tatrys, was leading a rebellion. In 1091, three autonomous, probably Pecheneg,[61] rulers were mentioned in the Alexiad: Tatos (Τατοῦ) or Chalis (χαλῆ), in the area of Dristra (probably the same person as Tatrys),[62] and Sesthlav (Σεσθλάβου) and Satza (Σατζά) in the area of Vicina.[63] The Cumans moved into Dobruja in 1094 and were influential in the region until the advent of the Ottoman Empire.[64]

Second Bulgarian Empire and Mongol domination

In 1187 the Byzantines lost control of Dobruja to the restored Bulgarian Empire. In 1241, the first

In the second part of the 13th century, the Turco–Mongolian

The war with the Tatars continued. In 1278, after a new Tatar invasion in Dobruja, Ivailo was forced to retreat to the strong fortress of Silistra, where he withstood a three-month siege.[77] In 1280 the Bulgarian nobility, which feared the growing influence of the peasant emperor, organised a coup. Ivailo had to flee to his enemy the Tatar Nogai Khan, who later killed him.[78] In 1300 Toqta, the new Khan of the Golden Horde, ceded Bessarabia to Emperor Theodore Svetoslav.[79]

Autonomous Dobruja

In 1325, the

Between 1352 and 1359, with the collapse of Golden Horde rule in Northern Dobruja, a new state appeared. It was controlled by

In 1357 Dobrotitsa was mentioned as a

In 1368, after the death of prince Demetrius, Dobrotitsa was recognised as ruler by

Between 1370 and 1375, allied with Venice, Dobritsia challenged Genoese power in the Black Sea. In 1376, he tried to impose his son-in-law, Michael, as Emperor of

In 1386, Dobrotitsa died and was succeeded by

Wallachian rule

In 1388/1389 Dobruja (Terrae Dobrodicii—as mentioned in a document from 1390) and Dristra (Dârstor) came under the control of

The Ottomans recaptured Dobruja in 1397 and ruled it to 1404, although in 1401 Mircea strongly defeated an Ottoman army.

The defeat of Sultan Beyezid I by

After Mircea died in 1418, his son Mihail I fought against the amplified Ottoman attacks, eventually being killed in a battle in 1420. That year, Sultan Mehmed I conducted the definitive conquest of Dobruja by the Turks. Wallachia kept only the mouths of the Danube, but not for a long duration.

In the late 14th century, German traveller Johann Schiltberger described these lands as follows:[88]

I was in three regions, and all three were called Bulgaria. ... The third Bulgaria is there, where the Danube flows into the sea. Its capital is called Kaliakra.

Ottoman rule

Annexed by the Ottoman Empire in 1420, the region remained under Ottoman control until the late 19th century. Initially, it was organised as an udj (border province), included in the

18th-19th century Russo-Turkish Wars

The Russian Empire occupied Dobruja several times during the

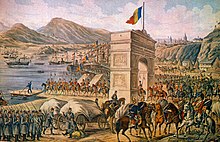

Russo-Turkish War of 1878 and aftermath

After the 1878 war, the Treaty of San Stefano awarded Dobruja to Russia and the newly established Principality of Bulgaria. The northern portion, held by Russia, was ceded to Romania in exchange for Russia obtaining territories in Southern Bessarabia, thereby securing direct access to the mouths of the Danube. The population included a Bulgarian ethnic enclave in the northeast (around Babadag), as well as an important Muslim majority (mostly Turks and Tatars) scattered around the region.

The southern portion, held by Bulgaria, was reduced the same year by the Treaty of Berlin. At the advice of the French envoy, a strip of land extended inland from the port of Mangalia (shown orange on the map) was ceded to Romania, since its southwestern corner contained a compact area of ethnic Romanians. The town of Silistra, located at the area's most southwestern point, remained Bulgarian due to its large Bulgarian population. Romania subsequently tried to occupy the town as well, but in 1879 a new international commission allowed Romania to occupy only the fort Arab Tabia, which overlooked Silistra, but not the town itself.

At the beginning of the

According to Bulgarian historians, after 1878 the Romanian church authorities took control over all local churches, with the exception of two in the towns of Tulcea and Constanţa, which managed to retain use of their Bulgarian Slavonic liturgy.[94] Between 1879 and 1900, Bulgarians built 15 new churches in Northern Dobruja.[95] After 1880, Italians from Friuli and Veneto settled in Greci, Cataloi and Măcin in Northern Dobruja. Most of them worked in the granite quarries in the Măcin Mountains, while some became farmers.[96] The Bulgarian authorities encouraged the settling of ethnic Bulgarians in the territory of Southern Dobruja.[97]

Balkan Wars and World War I

In May 1913, the

In 1923 the

World War II and aftermath

During

In 1948 and again in 1961–1962, Bulgaria proposed a border rectification in the area of Silistra, consisting mainly of the transfer of a Romanian territory containing the water source of that city. Romania made an alternative proposal that did not involve a territorial change and, ultimately, no rectification took place.[99]

In Romania, 14 November is a holiday observed as Dobruja Day.[100]

Demographic history

Ottoman era

On account of the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774), one of the greatest migration events of the region occurred where an estimated 200,000 Tatars emigrated to the Dobruja region between 1770 and 1784. Whereas, a large group of Christians (likely Greeks and Slavs) moved the other direction into the Tatar's recently-loss region of Azov in 1778.[101]

During Ottoman rule, groups of

In the second part of the nineteenth century, Ruthenians from the Austrian Empire also settled in the Danube Delta. After the Crimean War, a large number of Tatars were forcibly driven away from Crimea, immigrating to then-Ottoman Dobruja and settling mainly in the Karasu Valley in the centre of the region and around Bābā Dāgh. In 1864, Circassians fleeing from the Russian invasion and genocide of the Caucasus were settled in the wooded region near Babadag, forming a community there. Germans from Bessarabia also founded colonies in Dobruja between 1840 and 1892.

According to Bulgarian historian Lyubomir Miletich, most Bulgarians living in Dobruja in 1900 were nineteenth-century settlers or their descendants.[102][103] In 1850, the scholar Ion Ionescu de la Brad, wrote in a study on Dobruja, ordered by the Ottoman government, that Bulgarians came to the region "in the last twenty years or so".[104] According to his study, there were 2,285 Bulgarian families (out of 8,194 Christian families) in the region,[105] 1,194 of them in Northern Dobruja.[106] Lyubomir Miletich puts the number of Bulgarian families in Northern Dobruja in the same year at 2,097.[107] According to the statistics of the Bulgarian Exarchate, before 1877 there were 9,324 Bulgarian families out of a total 12,364 Christian families in the Northern Dobruja.[108][verification needed] According to Russian knyaz Vladimir Cherkassky, chief of the Provisional Russian government in Bulgaria in 1877–1878, the Bulgarian population in Dobruja was larger than the Romanian one.[108] However, count Shuvalov, the Russian representative to the Congress of Berlin, stated that Romania deserved Dobruja "more than anybody else, because of its population".[109] In 1878, the statistics of the Russian governor of Dobruja, Bieloserkovitsch, showed a number of 4,750 Bulgarian "family chiefs" (out of 14,612 Christian family chiefs) in the northern half of the region.[106]

The Christian religious organisation of the region was put under the authority of the

20th century

In 1913, Dobruja was all made part of Romania in the aftermath of the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest which ended the Second Balkan War. Romania acquired Southern Dobruja from Bulgaria, a territory with a population of 300,000 from which only 6,000 (2%) were Romanians.[113] In 1913, Romanian-held Northern Dobruja had a population of 380,430, from which 216,425 (56.8%) were Romanians.[114] Thus, when Dobruja was unified within Romania in 1913, there were over 222,000 Romanians in the region out of a total population of 680,000, or nearly 33% of the population. By 1930, the Romanian population within Dobruja had increased to 44.2%.[115]

Northern Dobruja

| Ethnicity | 1878[116] | 1880[117] | 1899[117] | 1913[114] | 19301[118] | 1956[119] | 1966[119] | 1977[119] | 1992[119] | 2002[119] | 2011[120] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 225,692 | 139,671 | 258,242 | 380,430 | 437,131 | 593,659 | 702,461 | 863,348 | 1,019,766 | 971,643 | 897,165 |

| Romanian | 46,504 (21%) | 43,671 (31%) | 118,919 (46%) | 216,425 (56.8%) | 282,844 (64.7%) | 514,331 (86.6%) | 622,996 (88.7%) | 784,934 (90.9%) | 926,608 (90.8%) | 883,620 (90.9%) | 751,250 (83.7%) |

| Bulgarian | 30,177 (13.3%) | 24,915 (17%) | 38,439 (14%) | 51,149 (13.4%) | 42,070 (9.6%) | 749 (0.13%) | 524 (0.07%) | 415 (0.05%) | 311 (0.03%) | 135 (0.01%) | 58 (0.01%) |

| Turkish | 48,783 (21.6%) | 18,624 (13%) | 12,146 (4%) | 20,092 (5.3%) | 21,748 (5%) | 11,994 (2%) | 16,209 (2.3%) | 21,666 (2.5%) | 27,685 (2.7%) | 27,580 (2.8%) | 22,500 (2.5%) |

| Tatar | 71,146 (31.5%) | 29,476 (21%) | 28,670 (11%) | 21,350 (5.6%) | 15,546 (3.6%) | 20,239 (3.4%) | 21,939 (3.1%) | 22,875 (2.65%) | 24,185 (2.4%) | 23,409 (2.4%) | 19,720 (2.2%) |

| Russian-Lipovan | 12,748 (5.6%) | 8,250 (6%) | 12,801 (5%) | 35,859 (9.4%) | 26,210 (6%)2 | 29,944 (5%) | 30,509 (4.35%) | 24,098 (2.8%) | 26,154 (2.6%) | 21,623 (2.2%) | 13,910 (1.6%) |

| Ruthenian (Ukrainian from 1956) |

455 (0.3%) | 13,680 (5%) | 33 (0.01%) | 7,025 (1.18%) | 5,154 (0.73%) | 2,639 (0.3%) | 4,101 (0.4%) | 1,465 (0.1%) | 1,177 (0.1%) | ||

| Dobrujan Germans | 1,134 (0,5%) | 2,461 (1.7%) | 8,566 (3%) | 7,697 (2%) | 12,023 (2.75%) | 735 (0.12%) | 599 (0.09%) | 648 (0.08%) | 677 (0.07%) | 398 (0.04%) | 166 (0.02%) |

| Greek | 3,480 (1.6%) | 4,015 (2.8%) | 8,445 (3%) | 9,999 (2.6%) | 7,743 (1.8%) | 1,399 (0.24%) | 908 (0.13%) | 635 (0.07%) | 1,230 (0.12%) | 2,270 (0.23%) | 1,447 (0.16%) |

| Roma | 702 (0.5%) | 2,252 (0.87%) | 3,263 (0.9%) | 3,831 (0.88%) | 1,176 (0.2%) | 378 (0.05%) | 2,565 (0.3%) | 5,983 (0.59%) | 8,295 (0.85%) | 11,977 (1.3%) |

- 1According to the 1926–1938 Romanian administrative division (counties of Constanța and Tulcea), which excluded a part of today's Romania (chiefly the communes of Ostrov and Lipnița, now part of Constanța County) and included a part of today's Bulgaria (parts of General Toshevo and Krushari municipalities)

- 2Only Russians. (Russians and Lipovans counted separately)

Southern Dobruja

| Ethnicity | 1910 | 19301[118] | 2001[121] | 2011[122] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 282,007 | 378,344 | 357,217 | 283,3953 |

| Bulgarian | 134,355 (47.6%) | 143,209 (37.9%) | 248,382 (69.5%) | 192,698 (68%) |

| Turkish | 106,568 (37.8%) | 129,025 (34.1%) | 76,992 (21.6%) | 72,963 (25.75%) |

| Roma | 12,192 (4.3%) | 7,615 (2%) | 25,127 (7%) | 12,163 (4.29%) |

| Tatar | 11,718 (4.2%) | 6,546 (1.7%) | 4,515 (1.3%) | 808 (0.29%) |

| Romanian | 6,348 (2.3%)2 | 77,728 (20.5%) | 591 (0.2%)2 | 947 (0.33%) |

- 1According to the 1926–1938 Romanian administrative division (counties of Durostor and Caliacra), which included a part of today's Romania (chiefly the communes of Ostrov and Lipnița, now part of Constanța County) and excluded a part of today's Bulgaria (parts of General Toshevo and Krushari municipalities)

- 2Including persons counted as Vlachs in Bulgarian Census

- 3Only includes persons who answered the optional question on ethnic identity. The total population was 309,151.

Area, population and cities

The entire region of Dobruja has an area of around 23,100 km2 (8,919 sq mi) and a population of around 1.2 million, of which just over two-thirds of the former and nearly three-quarters of the latter lie in the Romanian part.

| Ethnicity | Dobruja | Romanian Dobruja[120] | Bulgarian Dobruja[122] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |

| All | 1,180,560 | 100.00% | 897,165 | 100.00% | 283,395 | 100.00% |

| Romanian | 752,197 | 63.72% | 751,250 | 83.74% | 947 | 0.33% |

| Bulgarian | 192,756 | 16.33% | 58 | 0.01% | 192,698 | 68% |

| Turkish | 95,463 | 8.09% | 22,500 | 2.51% | 72,963 | 25.75% |

| Tatar | 20,528 | 1.74% | 19,720 | 2.20% | 808 | 0.29% |

| Roma | 24,140 | 2.04% | 11,977 | 1.33% | 12,163 | 4.29% |

| Russian | 14,608 | 1.24% | 13,910 | 1.55% | 698 | 0.25% |

| Ukrainian | 1,250 | 0.11% | 1,177 | 0.13% | 73 | 0.03% |

| Greek | 1,467 | 0.12% | 1,447 | 0.16% | 20 | 0.01% |

Major cities are Constanța, Tulcea, Medgidia and Mangalia in Romania, and Dobrich and Silistra in Bulgaria.

See also

- Bulgaria during World War I

- Romania during World War I

Notes

- ^ "Dobruja". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- OCLC 165781151.

- ^ A. Ischirkoff, Les Bulgares en Dobroudja, p. 4, attributes this opinion, among others, to Johann Christian von Engel, Felix Philipp Kanitz, Marin Drinov, Josef Jireček, Grigore Tocilescu

- ^ Paul Wittek, Yazijioghlu 'Ali on the Christian Turks of the Dobruja, p. 639

- OCLC 11916334.

- ^ A. Ischirkoff, Les Bulgares en Dobroudja, p. 4, attributes this opinion to Camille Allard, Ami Boué, Heinrich Brunn

- ^ G. Dănescu, Dobrogea (La Dobroudja). Étude de Géographie physique et ethnographique, pp. 35–36

- ^ Paul Wittek, Yazijioghlu 'Ali on the Christian Turks of the Dobruja, p. 653

- ISBN 978-90-04-07026-4.

- ^ A. Ischirkoff, Les Bulgares en Dobroudja, p. 4

- ^ A. Ischirkoff, Les Bulgares en Dobroudja, pp. 5–7

- )

- ^ Stănciugel, Robert; Bălaşa, Liliana Monica (2005). Dobrogea în Secolele VII–XIX. Evoluţie istorică (in Romanian). București. pp. 68–70.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - OCLC 26010612.

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, p. 13

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, p. 30

- ^ Eusebios–Hieronymos (2005). Ibarez, Josh Miguel Blasco (ed.). Hieronymi Chronicon (in Latin). p. 167. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ Aristotle (2000). ""Politics", Book V, 6". In Jowett, Benjamin (ed.). Aristotle's Politics. Adelaide: University of Adelaide. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ C. Müller, Fragmenta historicorum Graecorum, Paris, 1841, I, pp. 170–173

- OCLC 1610641. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- OCLC 7727833. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, Book VII, Ch. 98

- OCLC 11259464. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- OCLC 688941.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book LI, Ch. 26, Vol VI, pp. 75–77

- OCLC 24312572. Archived from the originalon 2006-04-24. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ Iordanes, The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, Ch. XVIII Archived 2006-04-24 at the Wayback Machine, sect. 101–102

- OCLC 56628978.

- OCLC 54878095. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ^ S. Vaklinov, "Формиране на старобългарската култура VI–XI век", p. 65

- ^ S. Vaklinov, "Формиране на старобългарската култура VI–XI век", pp. 48-50

- ^ S. Vaklinov, "Формиране на старобългарската култура VI–XI век", p. 64

- ^ I. Barnea, Şt.Ştefănescu, Bizantini, romani și bulgari la Dunărea de Jos, p. 28

- ^ Petar Mutafchiev, Добруджа. Сборник от Студии, Sofia,

- ^ Веселин Бешевлиев, "Формиране на старобългарската култура VI-XI век", София, 1977, стр. 97–103.

- OCLC 177289940.

- ^ A. Kuzev, V. Gyuzelev (eds.) Градове и крепости но Дунава и Черно море, pp. 16–44.

- ^ A. Kuzev, V. Gyuzelev (eds.), Градове и крепости но Дунава и Черно море, pp. 45-91.

- ^ A. Kuzev, V. Gyuzelev (eds.), Градове и крепости но Дунава и Черно море, pp. 179, 257, 294.

- ^ I. Barnea, Şt.Ştefănescu, Bizantini, romani și bulgari la Dunărea de Jos, p. 11

- ^ A. Kuzev, V. Gyuzelev (eds.), Градове и крепости но Дунава и Черно море, p. 257.

- ^ A. Kuzev, V. Gyuzelev (eds.), Градове и крепости но Дунава и Черно море, p. 293.

- ^ S. Vaklinov, "Формиране на старобългарската култура VI-XI век", p. 65.

- OCLC 5310246.

- ^ V Beshevliev, "Първобългарски надписи"

- ^ A. Kuzev, V. Gyuzelev (eds.), Градове и крепости но Дунава и Черно море, p. 186.

- ^ I. Barnea, Şt.Ştefănescu, Bizantini, romani şi bulgari la Dunărea de Jos, p. 71

- ISBN 978-5-02-008918-1. Archived from the originalon 2006-09-07.

- OCLC 15533292.

- ^ V. Mărculeţ, Asupra organizării teritoriilor bizantine de la Dunărea de Jos în secolele X-XII

- ISBN 978-973-8179-38-7. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2009-10-27. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ISSN 0132-3776.

- OCLC 64824669. Archived from the original(PDF) on March 9, 2008. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- ^ I. Barnea, Şt.Ştefănescu, Bizantini, romani și bulgari la Dunărea de Jos, pp. 112–115

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, pp. 184–185

- Candidate Dissertation. Typewritten (in Bulgarian). Sofia: 79–81.)

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help - ^ S. Vaklinov, "Формиране на старобългарската култура VI-XI век", pp. 79–81.

- ^ I. Barnea, Şt.Ştefănescu, Bizantini, romani și bulgari la Dunărea de Jos, pp. 122–123

- ^ Cedrenus, Historiarum compendium, II, s. 514–515 Archived April 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cedrenus, Historiarum compendium, II, s. 582–584 Archived April 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- OCLC 38636706. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-10. Retrieved 2007-05-16.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)). This opinion is supported by modern historians (Madgearu, Alexandru (1999). "Dunărea în epoca bizantină (secolele X-XII): o frontieră permeabilă" (PDF). Revista istorică (in Romanian). 10 (1–2): 48–49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-09. Retrieved 2007-04-16.). They were considered to be Vlach or Russian by some authors. For a survey of these opinions see I. Barnea, Şt.Ştefănescu, Bizantini, romani şi bulgari la Dunărea de Jos, pp. 139–147 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-16.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link - ^ I. Barnea, Şt.Ştefănescu, Bizantini, romani şi bulgari la Dunărea de Jos, pp. 136, 141

- OCLC 67891792. Archived from the originalon 2020-04-13. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, pp. 192–193

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, p. 194

- ^ P. Wittek, Yazijioghlu 'Ali on the Christian Turks of the Dobruja, pp. 640, 648

- ^ P. Wittek, Yazijioghlu 'Ali on the Christian Turks of the Dobruja, pp. 648, 658

- OCLC 50096285. Archived from the originalon January 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- ^ Ив. К. Димитровъ, Прѣселение на селджукски турци въ Добруджа около срѣдата на XIII вѣкъ, стр. 32—33

- ^ Dimitri Korobeinikov, "A broken mirror: the Kipçak world in the thirteenth century", In: The Other Europe from the Middle Ages, Edited by Florin Curta, Brill 2008, p. 396

- ISBN 978-954-427-216-6.

- ^ Pachymeres, ib., pp. 230-231

- ^ Ив. К. Димитровъ, каз. стат., стр. 33–34

- ^ Васил Н. Златарски, История на българската държава през срeднитe вeкове. Том III. Второ българско царство. България при Асeневци (1187–1280), стр. 517

- ^ П. Ников, каз. съч., стр. 143

- ^ Васил Н. Златарски, История на българската държава през срeднитe вeкове. Том III. Второ българско царство. България при Асeневци (1187–1280), стр. 545-549

- ^ Y. Andreev, M. Lalkov, Българските ханове и царе, p. 226

- ^ Васил Н. Златарски, История на българската държава през срeднитe вeкове. Том III. Второ българско царство. България при Асeневци (1187—1280), стр. 554

- ^ Y. Andreev, M. Lalkov, Българските ханове и царе, p. 247

- ^ Miklosich, Franz; Müller, eds. (1860). "LXIII. 6883—1325 maio-iunio ind. VIII. Synodus dirimit sex controversias". Acta et diplomata Graeca medii aevi sacra et profana, vol. I. Vien: Carolus Gerold. p. 135.

- ^ Names of the rulers of the Principality of Karvuna are given here as spelled in modern Bulgarian and Romanian, respectively.

- OCLC 17356688. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ^ Miller, Timothy S. (1975). "The War of Galata, according to the History of John Cantacuzenus (1348)". The History of John Cantacuzenus (Book IV): Text, Translation and Commentary. Catholic University of America. Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-04-28 – via De Re Militari.

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, p. 197

- ^ I. Barnea, Şt.Ştefănescu, Bizantini, romani și bulgari la Dunărea de Jos, p. 351

- ^ Miklosich, Franz; Müller, eds. (1860). "CLXVI. (6865—1357) iunio ind. X. Synodus metropolitae Mesembriae restituit duo castella". Acta et diplomata Graeca medii aevi sacra et profana, vol. I. Vien: Carolus Gerold. p. 367.

- ISBN 978-90-04-07026-4.

- ^ Delev, Petǎr; Valeri Kacunov; Plamen Mitev; Evgenija Kalinova; Iskra Baeva; Bojan Dobrev (2006). "19. Bǎlgarija pri Car Ivan Aleksandǎr". Istorija i civilizacija za 11. klas (in Bulgarian). Trud, Sirma.

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, p. 205

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, p. 249

- ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7.

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, p. 333

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, pp. 358–360

- ^ Kosev et al., Възстановяване и утвърждаване на българската държава p. 416

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, p. 365

- România Liberă (in Romanian). Archived from the originalon June 7, 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, pp. 363-364, 381

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, p. 430

- ^ Cojoc, Mariana; Tiță, Magdalena (2006-09-06). "Proiecții teritoriale bulgare". Ziua de Constanţa (in Romanian). Retrieved 2007-02-15.

- ^ "Ziua Dobrogei". Agerpres (in Romanian). 14 November 2019. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-521-57456-3.

- OCLC 67304814.

- OCLC 65828513.

- OCLC 251025693.

- ^ Lampato, Francesco, ed. (1851). Annali universali di statistica, economia, pubblica, geografia, storia, viaggi e commercio (in Italian). Milano: Presso la Societa' degli Editori degli Annali Universali delle Scienze e dell'Industria. p. 211.

- ^ a b Seişanu, Romulus (1928). Dobrogea. Gurile Dunării şi Insula Şerpilor. Schiţă monografică (in Romanian). București: Tipografia ziarului "Universul". p. 177.

- ^ L. Miletich, Старото българско население в северо-източна България, pp. 169–170

- ^ OCLC 63809870.

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, p. 337

- ^ Kosev et al., Възстановяване и утвърждаване на българската държава, pp. 460–461

- ^ Baron d'Hogguer (February 1879). Informaţiuni asupra Dobrogei. Starea eĭ de astăḍi. Resursele şi viitorul ei (in Romanian). Bucureşci: Editura Librăriei SOCEC.

- ^ A. Rădulescu, I. Bitoleanu, Istoria Dobrogei, pp. 322–323

- ^ U.S. Government Printing Office, 1957, Documents on German foreign policy, 1918–1945, from the archives of the German Foreign Ministry, p. 336

- ^ )

- ^ Lucian Boia, Central European University Press, 2001, History and Myth in Romanian Consciousness, p. 182

- ^ K. Karpat, : Correspondance Politique des Consuls. Turguie (Tulqa). 1 (1878) 280-82

- ^ a b G. Dănescu, Dobrogea (La Dobroudja). Étude de Géographie physique et ethnographique

- ^ OCLC 1983592.

- ^ a b c d e Calculated from statistics for the counties of Tulcea and Constanța from "Populația după etnie la recensămintele din perioada 1930–2002, pe judete" (PDF) (in Romanian). Guvernul României — Agenţia Națională pentru Romi. pp. 5–6, 13–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- ^ a b 2011 census results per county, cities and towns "Populaţia stabilă pe sexe, după etnie – categorii de localităţi, macroregiuni, regiuni de dezvoltare şi judeţe" (in Romanian). Institutul Național de Statistică. Archived from the original (XLS) on 2019-08-15. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ^ Calculated from the results of the 2001 Bulgarian census for the administrative regions of Dobrich and Silistra, from "Население към 01.03.2001 г. по области и етническа група" (in Bulgarian). Националния статистически институт. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- ^ a b Calculated from the results of the 2011 Bulgarian census for the administrative regions of Dobrich and Silistra, from "Население по етническа група и майчин език" (in Bulgarian). Националния статистически институт. Archived from the original on 2015-12-19. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

References

- Dănescu, Grigore (1903). Dobrogea (La Dobroudja). Étude de Géographie physique et ethnographique (in French). Bucarest: Imprimerie de l'Indépendance Roumaine. OCLC 10596414.

- OCLC 4061330.

- Wittek, Paul (1952). "Yazijioghlu 'Ali on the Christian Turks of the Dobruja". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 14 (3). Cambridge University Press on behalf of S2CID 140172969.. Subscription needed for online access.

- Barnea, Ion; Ștefănescu, Ștefan (1971). Bizantini, romani și bulgari la Dunărea de Jos. Din Istoria Dobrogei (in Romanian). Vol. 3. București: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România. OCLC 1113905.

- Vaklinov, Stancho (1977). Формиране на старобългарската култура VI-XI век (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Издателство Наука и Изкуство. OCLC 71440284.

- Kuzev, Aleksandar; Gyuzelev, Vasil, eds. (1981). Градове и крепости но Дунава и Черно море. Български средновековни градове и крепости (in Bulgarian). Vol. 1. Varna: Книгоиздателство "Георги Бакалов". OCLC 10020724.

- Rădulescu, Adrian; Bitoleanu, Ion (1998). Istoria Dobrogei (in Romanian). Constanţa: Editura Ex Ponto. ISBN 978-973-9385-32-9.

- Mărculeţ, Vasile (2003). "Asupra organizării teritoriilor bizantine de la Dunărea de Jos în secolele X-XII: thema Mesopotamia Apusului, strategatul Dristrei, thema Paristrion – Paradunavon". In Dobre, Manuela (ed.). Istorie şi ideologie (in Romanian). București: Editura Universității din București. ISBN 978-973-575-658-1. Archived from the originalon 2018-04-18. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- ISBN 978-973-50-0551-1.

Further reading

- OCLC 250411. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- Rădulescu, Adrian; Bitoleanu, Ion (1979). Istoria românilor dintre Dunăre şi Mare: Dobrogea (in Romanian). București: Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică. OCLC 5832576.

- Iordachi, Constantin (2001), "The California of the Romanians": The Integration of Northern Dobrogea into Romania, 1878-1913, in Nation-Building and Contested Identities Romanian & Hungarian Case Studies

- Sallanz, Josef, ed. (2005). Die Dobrudscha. Ethnische Minderheiten, Kulturlandschaft, Transformation; Ergebnisse eines Geländekurses des Instituts für Geographie der Universität Potsdam im Südosten Rumäniens. (= Praxis Kultur- und Sozialgeographie; 35) (in German) (II ed.). Potsdam: Universitätsverlag Potsdam. ISBN 978-3-937786-76-6.

- Sallanz, Josef (2007). Bedeutungswandel von Ethnizität unter dem Einfluss von Globalisierung. Die rumänische Dobrudscha als Beispiel. (= Potsdamer Geographische Forschungen; 26) (in German). Potsdam: Universitätsverlag Potsdam. ISBN 978-3-939469-81-0.