Don Merton

Don Merton CF | |

|---|---|

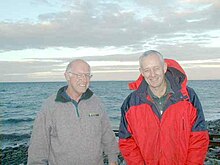

Merton (left) with Dave Barker on Hauturu (Little Barrier Island) | |

| Born | Donald Vincent Merton 22 February 1939 Auckland, New Zealand |

| Died | 10 April 2011 (aged 72) Tauranga, New Zealand |

| Occupation | Conservationist |

| Employer | Department of Conservation |

| Relatives | Jan Tinetti (daughter-in-law) |

Donald Vincent Merton

When Merton began his work as a conservationist, kākāpō were believed to be extinct, but about 20 years into his career a small population was found in a semi-remote national park in mainland New Zealand. However, it was several months before they finally found a female, and soon after they found the first female they discovered a surprise, well-fed chick a few weeks old. Merton and his crew initially wanted to relocate all of the rediscovered kākāpō they found to Codfish Island, but the New Zealand Department of Conservation only gave permission to relocate 20. Despite the limited relocation, the kākāpō population has steadily recovered (as of 2019 there are 147 mature adult kākāpō, and the 2019 season produced 181 eggs and 34 chicks so far, though not all are likely to survive due to problems with in breeding- lack of genetic diversity). With technological advances in genome mapping tools like CRISPR, scientists have successfully mapped all of the 147 kākāpō genomes, and in the near future it may be possible to edit the genomes of an egg to allow for a higher survival rate among newly hatched chicks.[citation needed]

Until his retirement in April 2005, Merton was a senior member of the New Zealand Department of Conservation's Threatened Species Section, within the Research, Development & Improvement Division, Terrestrial Conservation Unit, and of the Kakapo Management Group. He had a long involvement in wildlife conservation, specialized in the management of endangered species since he completed a traineeship with the New Zealand Wildlife Service (NZWS) in 1960.[1]

Early life

Merton was born in Devonport, Auckland in February 1939 and with his family moved to Gisborne later that year when his father, Glaisher (Major) Merton was appointed the first New Zealand Automobile Association representative in the Poverty Bay region. Initially, the family settled at Wainui Beach near Gisborne, but in 1945 moved to a farmette in Mangapapa Road, Gisborne.

Together with his two older brothers, Merton had early success

Merton attended schools at Kaiti, Mangapapa, Gisborne Intermediate and Gisborne High School. On leaving school he secured a traineeship with the fledgeling New Zealand Wildlife Service. In 1987 the Wildlife Service merged with other Government conservation agencies to form the Department of Conservation. In the early 1960s, Merton became one of only two field officers working nationally on threatened species, roles now filled by more than 80 staff.

Professional achievements

Together with NZWS colleagues and volunteers, his contributions include:

- pioneered capture and New Zealand birds – including establishment of a second population of the North Island saddleback, and averting extinction of the South Island saddleback. Techniques pioneered then are now an everyday part of threatened species management within NZ and beyond;

- pioneered "close order management" (COM) as a means of averting extinction; sustaining in the wild; and/or facilitating recovery of critically endangered species. COM involves intensive management of free-living animals at the individual rather than population level. The concept and techniques were developed and applied with outstanding success during the rescue and recovery of the black robin which Merton led in the 1980s. Refined and adapted over the years, close order management techniques pioneered then are now an integral part of threatened species recovery programmes internationally.[5]

- helped pioneer island biodiversity conservation and restoration techniques. For instance, in the early 1960s, he and Royal Forest & Bird Protection Society of New Zealand volunteers eradicated Norway rats from four small islands in the Noises group, Hauraki Gulf. This was the first time that rats had been deliberately eradicated from a New Zealand island and opened the way for ecological restoration of these – and many other islands both within New Zealand and beyond;

- led the NZWS field teams that re-discovered the kākāpō parrot (in Fiordland) in 1974, and females of this species (on Stewart Island) in 1980. Females had not been seen since the early 1900s and it was feared they may have been extinct – and thus the species "functionally extinct";

- discovered and documented the significance of the ritualised, nocturnal booming display of the kākāpō – it is, in fact, an unusual form of courtship display known as "lekking";

- instrumental in averting imminent extinction of kākāpō (an endemic, monotypic sub-family): In the early 1980s; (i) determined that the newly re-discovered kākāpō population of southern Stewart Island was in steep decline due to predation by feral cats (~53% mortality per annum of marked adults); (ii) alerted NZWS, drafted submissions and obtained agreement from the various government and other agencies to relocate (and thus effectively destroy) the last natural population; and, (iii) as NZWS's Principal Wildlife Officer (Endangered Species), assumed responsibility for planning and leading the capture and relocation of all remaining (61) birds to Little Barrier, Maud and Codfish Islands. This action proved very successful – the steep decline in kākāpō numbers was halted and adult mortality since (~30 years) has averaged a remarkably low ~1.3% per annum;

- led the field project and devised the techniques necessary to capture, hold in captivity, transport and establish a second population of the endangered and highly localised noisy scrubbird of Western Australia. The second population is now by far the larger of the two;

- during the 1980s helped devise and implement a recovery strategy for the critically endangered Mauritius parakeet of Mauritius(Indian Ocean). Only around eight birds including three females were known to exist at that time. There are now more than 300 in the wild;

- also during the 1980s, devised and led the successful eradication of rabbits from Round Island, Mauritius(Indian Ocean) – Round Island was said to support more threatened animal and plant forms than any comparable area on Earth, but survival of these was seriously threatened by the rabbits;

- instrumental in the designation of a national park within the Australian Territory of island ecosystem– while seconded for two years to the Australian National Parks & Wildlife Service as its first Conservator on Christmas Island;

- played a key role in the rescue and recovery of the magpie robin and other animals endemic to the Norway rats reached Fregate Island, (final refuge of the last natural population of Seychelles magpie robin and a number of other vulnerable endemic life-forms), alerted the island's owner, and local and international conservation agencies to the fact that without intervention ecological collapse and extinctions were inevitable. Worked with stakeholders and by 1999 convinced all that eradication was both necessary and practicable. At their request planned, and in 2000 led a successful rodent (Norway rat and house mouse) eradication – thus averting extinctions and facilitating ecological recovery.

- authored or co-authored ~150 publications, including books, peer-reviewed scientific papers, popular articles and technical reports.

In New Zealand Merton is also known for his role in the rescue of the South Island saddleback when in the early 1960s rats

Later life and death

Merton retired from the Department of Conservation in 2005.[6] He lived in Tauranga where he remained active in conservation issues, and died there from pancreatic cancer on 10 April 2011.[7]

Honours and awards

Merton was awarded a

As well as being the recipient of numerous awards the Don Merton Conservation Pioneer Award is named after him.[10]

See also

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7900-1159-2.

- ISBN 0-19-558260-8.

- .

- ^ DOC, Media release (13 January 2011). "Kākāpō males 'boom' on as legendary bird dies". NZ Department of Conservation. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Merton, Don (1992). "Guest Editorial: The Legacy of "Old Blue"" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 16 (2): 65–68.

- ^ "Don Merton, 1939–2011: internationally acclaimed conservation pioneer". Department of Conservation. 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ "New Zealand conservationist Don Merton dies". Stuff.co.nz. 10 April 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ "No. 51774". The London Gazette (3rd supplement). 17 June 1989. p. 33.

- ^ Listener, NZ (3–9 July 1999). "100 Great New Zealanders of the 20th Century". 60th Anniversary Issue of the New Zealand Listener. 169 (3086): 16–21.

- ^ "Dr Don Merton immortalised in new award". New Zealand Government (Beehive). 29 October 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

Further reading

- Butler, David; Merton, Don. The Black Robin. 1992. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-558260-8

- Jim Kidson: "Don Merton on the side of the Underdog" (page 15–17) in: Forest&Bird Magazine, February 1989. Forest&Bird Protection Society of New Zealand, P.O.Box 631, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Ballance, Alison [text] & Don Merton [photos] 2007: "Don Merton, the man who saved the Black Robin", Reed Publishing (NZ) Ltd., Auckland. ISBN 0-7900-1159-X; 367pp.

External links

- "Winging it" – an interview with Don Merton at New Zealand Listener

- Don Merton's biography – Kakapo Recovery Team