Douglas DC-2

| DC-2 | |

|---|---|

| |

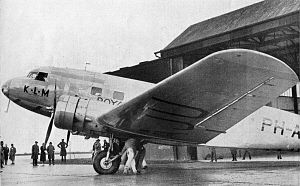

| DC-2 PH-AJU Uiver came second in the MacRobertson Air Race in 1934 | |

| Role | Passenger & military transport |

| Manufacturer | Douglas Aircraft Company |

| First flight | May 11, 1934 |

| Introduction | May 18, 1934, with Trans World Airlines |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | Pan American Airways

|

| Produced | 1934–1939 |

| Number built | 192 |

| Developed from | Douglas DC-1 |

| Developed into | Douglas B-18 Bolo Douglas DC-3 |

The Douglas DC-2 is a 14-passenger, twin-engined airliner that was produced by the American company Douglas Aircraft Company starting in 1934. It competed with the Boeing 247. In 1935, Douglas produced a larger version called the DC-3, which became one of the most successful aircraft in history.

Design and development

In the early 1930s, fears about the safety of wooden aircraft structures drove the US aviation industry to develop all-metal airliners.

The Douglas response was more radical. When it flew on July 1, 1933, the prototype DC-1 had a robust tapered wing, retractable landing gear, and two 690 hp (515 kW) Wright radial engines driving variable-pitch propellers. It seated 12 passengers.

Douglas test pilot Carl Cover flew the first test flight on May 11, 1934, of the DC-2 which was longer than the DC-1, had more powerful engines, and carried 14 passengers in a 66-inch-wide cabin. TWA was the launch customer for the DC-2 ordering twenty. The design impressed American and European airlines and further orders followed. Although Fokker had purchased a production licence from Douglas for $100,000 (about $2,224,000 in 2022) no manufacturing was done in The Netherlands. Those for European customers KLM, LOT, Swissair, CLS and LAPE purchased via Fokker in the Netherlands were built and flown by Douglas in the US, sea-shipped to Europe with wings and propellers detached, then erected at airfields by Fokker near the seaport of arrival (e.g. Cherbourg or Rotterdam).[1] Airspeed Ltd. took a similar licence for DC-2s to be delivered in Britain and assigned the company designation Airspeed AS.23, but although a registration for one aircraft was reserved none were built.[2] Another licence was taken by the Nakajima Aircraft Company in Japan; unlike Fokker and Airspeed, Nakajima built five aircraft as well as assembling at least one Douglas-built aircraft.[2] A total of 130 civil DC-2s were built with another 62 for the United States military. In 1935 Don Douglas stated in an article that the DC-2 cost about $80,000 (about$1,780,000 in 2022) per aircraft if mass-produced.[3]

Operational history

Although overshadowed by its ubiquitous successor, it was the DC-2 that first showed that passenger air travel could be comfortable, safe and reliable. As a token of this, KLM entered its first DC-2 PH-AJU Uiver (Stork) in the October 1934

Variants

Civilian

- DC-2

- 156 civil DC-2s, powered by two Wright R-1820 Cycloneradial piston engines of varying in power from 710 to 875 hp (529 to 652 kW) depending on model

- DC-2A

- Two civil DC-2s, powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-1690 Hornet(SD-G, S1E-G or S2E-G) radial piston engines

- DC-2B

- Two DC-2s sold to Bristol Pegasus VI radial piston engines[5]

- Nakajima-Douglas DC-2 transport

- DC-2 transports license built in Japan by Nakajima

- Airspeed AS.23

- The designation reserved for proposed license-built production by Airspeed Ltd. in Great Britain

Military

Modified DC-2s built for the United States Army Air Corps under several military designations:

- XC-32

- (DC-2-153) One aircraft, powered by two 750 hp (560 kW) Wright R-1820-25 radial piston engines, for evaluation as a 14-seat VIP transport aircraft, one built,[6] later used by General Andrews as a flying command post[7]

- C-32A

- Designation for 24 commercial DC-2s impressed at the start of World War II[6]

- C-33

- (DC-2-145) Cargo transport variant of the C-32 powered by two 750 hp (560 kW) Wright R-1820-25 engines, with larger vertical tail surfaces, a reinforced cabin floor and a large cargo door in the aft fuselage, 18 built[6]

- YC-34

- (1x DC-2-173 & 1x DC-2-346) VIP transport for the secretary of war, basically similar to XC-32, later designated C-34, two built[8]

- C-38

- The first C-33 was modified with a DC-3-style tail section and two Wright R-1820-45 radial piston engines of 975 hp (727 kW) each. Originally designated C-33A but redesignated as prototype for C-39 variant, one built.[9]

- C-39

- (DC-2-243) 16-seat passenger variant, a composite of DC-2 and DC-3 components, with C-33 fuselage and wings and DC-3-type tail, center-section and landing gear. Powered by two 975 hp (727 kW) Wright R-1820-45 radial piston engines; 35 built.[10]

- C-41

- The sole C-41 was a VIP aircraft for Air Corps Chief Oscar Westover (and his successor Douglas C-41A was also a VIP version of the DC-3A)[11]

- C-42

- (DC-2-267) VIP transport variant of the C-39, powered by two 1,000 hp (750 kW) Wright R-1820-53 radial piston engines, of 1,000 hp (746 kW) each, one built in 1939 for the commanding general, GHQ Air Force, plus two similarly-converted C-39s with their cargo doors bolted shut were converted in 1943.[11]

- R2D-1

- (3x DC-2-125 & 2x DC-2-142) 710 hp (530 kW) Wright R-1820-12-powered transport similar to the XC-32, three built for the United States Navy and two for the United States Marine Corps

Operators

♠ = Original operators

Civil operators

- CNAC, jointly owned and operated with Pan American Airlines

- ČLS (Československá Letecká Společnost, Czechoslovak Air Transport Company) ♠

- KNILM (Royal Netherlands Indies Airways) ♠

- Aero O/Y

- Great Northern Airways ♠

- Japan Air Transport

- Imperial Japanese Airways

- Aeronaves de Mexico

- Mexicana

- KLM ♠ ordered 18 aircraft.

- LOT Polish Airlines ♠ operated three DC-2B aircraft between 1935 and 1939

- Líneas Aéreas Postales Españolas♠ received five aircraft.

- Swissair ♠

- American Airlines ♠

- Braniff Airways

- Delta Air Lines operated four aircraft during 1940–1941

- Eastern Air Lines ♠ received 14 aircraft and used them on East Coast routes.

- General Air Lines♠

- Mercer Airlines♠ 1 airplane, sold to Colgate Darden in late 1960s, now in the Netherlands

- Pan American Airways ♠ received 16 aircraft, distributing many to its foreign affiliates; some flew under its own name on Central American routes.[citation needed]

- Pan American-Grace Airways (Panagra) ♠ used its DC-2s on routes within South America.

- Transcontinental & Western Air (TWA) was the first DC-2 operator, receiving 30 aircraft. ♠

- PLUNA operated two DC-2s acquired from Panair do Brasil.[citation needed]

Military and government operators

- Argentine Naval Aviation - 5 (+1) DC-2 ex civilian Venezuelan [13]

- Royal Australian Air Force - Ten aircraft were in service with the RAAF from 1940 to 1946.

- No. 8 Squadron RAAF

- No. 36 Squadron RAAF

- Parachute Training School RAAF

- Wireless Air Gunners School RAAF

- Austrian Government

- Finnish Air Force Donated by the Carl Gustaf von Rosen and KLM during the Winter War (1939-1940) which flew a bombing mission based on Tampere on 22 February 1940

- French government

- Regia Aeronautica 2 aircraft[14]

- Imperial Japanese Army Air Service - A single example of the DC-2 was impressed by the Imperial Japanese Army.[15]

- Spanish Republican Air Force took over the DC-2s from LAPE inventory.[16]

- United States Army Air Corps ♠

- United States Army Air Forces

- United States Marine Corps ♠

- United States Navy ♠

Incidents and accidents

- December 20, 1934: A Rutbah Wells in Iraq, killing all seven on board. The aircraft was operating a flight from Schiphol to Batavia.[17][18] This was the first loss of a DC-2 and the first fatal accident involving the DC-2.[citation needed]

- May 6, 1935: TWA Flight 6, a DC-2-115 (NC13785), hit terrain and crashed near Atlanta, Missouri, while flying low in poor visibility to reach a landing field before running out of fuel; this killed five of thirteen on board, including New Mexico Senator Bronson M. Cutting.[19]

- July 20, 1935: 1935 San Giacomo Douglas DC-2 crash: A KLM DC-2-115E (PH-AKG, Gaai) crashed on landing at Pian San Giacomo in bad weather, killing all 13 on board.[20]

- October 6, 1935: A Standard Oil Company DC-2A-127 (NC14285) crashed into Great Salt Lake, Utah; the three crew survived the crash, but drowned while trying to swim to safety.[21]

- January 14, 1936: American Airlines Flight 1, a DC-2-120 (NC14274), crashed into a swamp near Goodwin, Arkansas, for reasons unknown, killing all 17 on board.

- April 7, 1936: TWA Flight 1, a DC-2-112 (NC13721), crashed into Chestnut Ridge near Uniontown, Pennsylvania, in fog due to pilot error, killing 12 of 14 on board.

- October 10, 1936: A Pan American-Grace Airways DC-2-118B (NC14273) struck the side of a mountain near San Jose Pinula while being ferried from San Salvador to Guatemala City, killing the three crew.[22]

- December 9, 1936: A KLM DC-2-115E (PH-AKL, Lijster) autogiro, was among the dead.

- March 25, 1937: TWA Flight 15A, a DC-2-112 (NC13730), crashed into a small gully near Clifton, Pennsylvania, due to icing, killing all 13 on board.[23]

- July 28, 1937: A KLM DC-2-115L (PH-ALF, Flamingo) crashed into a field near Belligen, Belgium, after takeoff due to an in-flight fire, killing all 15 on board.[24]

- August 6, 1937: An Aeroflot DC-2-152 (URSS-M25) exploded in mid-air and crashed near Bistrita, Romania, killing all five on board.[25]

- August 10, 1937: Eastern Air Lines Flight 7, a DC-2-112 (NC13739), crashed on takeoff at Daytona Beach Airport after striking a power pole, killing four of nine on board.[26]

- August 23, 1937: A Pan American-Grace Airways DC-2-118A (NC14298) crashed and burned 20 mi north of San Luis, Argentina in dense fog, killing all three on board.[27]

- November 23, 1937: A LOT DC-2-115D (SP-ASJ) crashed in the Pirin mountains, killing all six occupants. The aircraft was operating a flight from Thessaloniki to Bucharest.[28]

- March 1, 1938: TWA Flight 8, a DC-2-112, crashed in Yosemite National Parkdue to severe weather, killing all nine on board; the wreckage was found three months later.

- July 19, 1938: A Pan American-Grace Airways DC-2-118A (NC14272, Santa Lucia) crashed into Mount Mercedario, killing all four on board; the wreckage was found in early 1941.[29]

- August 24, 1938: Kweilin Incident in China. The first commercial airplane in history to be shot down.[30]

- October 25, 1938: An Australian National Airways DC-2-210 (VH-UYC, Kyeema) crashed into Mount Dandenong due to weather and navigation errors, killing all 18 on board.

- December 8, 1938: An Imperial Japanese Airways Nakajima/Douglas DC-2 (J-BBOH, Fuji) crashed in the East China Sea off the Kerama Islands due to engine failure, killing 10 of 12 on board; the survivors were rescued by a steamship.[31]

- January 7, 1939: A

- March 26, 1939: Braniff Airways Flight 1, a DC-2-112 (NC13237), lost control and crashed on takeoff at Oklahoma City after an engine cylinder blew, killing eight of 12 on board.[33]

- May 10, 1940: Five KLM DC-2-115s (PH-ALD, PH-AKN, PH-AKO, PH-AKP, PH-AKK) were destroyed on the ground at Schiphol Airport by aircraft from Luftwaffe's Battle of the Netherlands.

- August 9, 1940: A Deutsche Luft Hansa DC-2-115E (D-AIAV) crashed near Lämershagen, Germany, due to pilot error, killing two of 13 on board.[34]

- October 29, 1940: Shootdown of the Chungking (previously the Kweilin).[35]

- January 4, 1941: US Navy R2D-1 9622 struck Mother Grundy Peak, 27 mi E of North Island NAS, killing all 11 on board.[36]

- February 12, 1941: A China National Aviation Corporation DC-2-190 (40, Kangting) struck a mountain near Taohsien, Hunan in a thunderstorm, killing the three crew.[37]

- July 1941: A Soviet Air Force DC-2-115F (ex. LOT SP-ASK) was destroyed on the ground at Spilve Airport by German fighters.[38]

- August 2, 1941: A US Treasury DC-2-120 (NC14729) was being delivered to the RAF when it crashed at Bathurst (now Banjul), Gambia, killing the three crew.[39]

- December 8, 1941: RAF DC-2-120 DG475 was shot down by three Luftwaffe Bf 110s and crashed 10 mi northeast of RAF LG-138 (Landing Ground 138) near Habata, Egypt, killing one.[40]

- March 5, 1942:USAAF C-39 38-525 crashed in the St. Lucie River off Port Sewall, Florida, due to wing separation after flying into a storm, killing all seven on board.[41]

- March 14, 1942: A China National Aviation Corporation DC-2-221 (31, Chungshan) crashed near Kunming, killing 13 of 17 on board.[42]

- May 25, 1942: USAAF C-39 38-505 crashed on takeoff from Alice Springs Airport in Australia due to overloading, killing all 10 on board.[43]

- September 14, 1942: RAAF DC-2-112 A30-5, of RAAF 36 Squadron, crashed while on approach to Seven Mile Strip, killing the five crew.[44]

- October 1, 1942: USAAF C-39 38-524 struck a hill at high speed 15 mi northwest of Coamo, Puerto Rico, due to an unexplained malfunction and low visibility, killing all 22 on board in the worst-ever accident involving the DC-2.[45]

- January 31, 1944: USAAF C-39 38-501 crashed near Sioux City AAB due to a possible engine fire, killing the three crew.[46]

- August 11, 1945

- A Mexicana DC-2-243 (XA-DOT) struck Iztaccihuatl Volcano in bad weather, killing all 15 on board.[47]

- February 7, 1951: Malmi Airport due to engine failure; the fuselage is preserved at the Suomen ilmailumuseo (Finnish Aviation Museum) in Helsinki.[48]

Surviving aircraft

Several DC-2s have survived and been preserved in the 21st century in the following museums in the following places:

- c/n 1286 - Ex-Eastern Airlines and RAAF, preserved (dressed as the historic "Uiver", PH-AJU) at Albury, New South Wales as centerpiece of Uiver Memorial at Albury Airport. This is the oldest DC-2 left in the world. It was removed from its prominent position on poles in front of the Albury Airport terminal building in late 2002, but unfortunately kept out in the open air without preservation. In 2014 after much debate and delays, Albury City Council transferred ownership of the plane to the Uiver Memorial Community Trust (UMCT). In January 2016 UMCT began work on removing the major assemblies of the aircraft, and on 12 May 2016 the airframe was transferred to a restoration hangar. Restoration of this aircraft to static display standard is now under way.[49]

- c/n 1288 - An Ex-Eastern Airlines and RAAF DC-2, it was exported and located for many years at the Aviodrome in the Netherlands though owned by the Dutch Dakota Association.[50] It was transferred to the Netherlands Transport Museum in 2018 and has been externally restored for static display as KNILM DC-2 PK-AFK.[51]

- c/n 1292 - There are three DC-2s surviving in Australia as of 2006; this aircraft, c/n 1292, is one of ten ex-Eastern Airlines DC-2s purchased and operated by the RAAF during World War II as A30-9. It is under restoration by the Victoria, Australia

- c/n 1354 - One DC-2-115E (reg. DO-1 (Hanssin-Jukka), ex. PH-AKH (Aviation Museum of Central Finland (Finnish Air Force Museum) and is on display in a hangar in Tuulos, Finland.[53] The plane was restored to display condition in 2011, in war-time colors. It performed one bombing raid in February 1940. Another wingless fuselage (c/n 1562, reg. DO-3, ex. OH-LDB "Sisu") was on display at the Finnish Aviation Museum in Vantaa.[54][55]The fuselage was transported to the Aviation Museum of Central Finland in 2011, where it was used in the DO-1 restoration project.

- c/n 1368 - A former TWA "The Lindbergh Line" livery and interior trim.[56]

- c/n 1376 - Owned by Steve Ferris in Sydney, Australia, and has been under restoration to flying status for many years.[citation needed] It was originally delivered to KNILM in 1935. At the outbreak of World War II it was flown to Australia and was conscripted into use with the Allied Directorate of Air Transport. In 1944 it joined Australian National Airways and finished its flying career in the 1950s with Marshall Airways. It is registered as VH-CDZ. It is the most complete of all the Australian DC-2s as of 2008.

- c/n 1404 - The General Air Linescolors and moved it to his private airport in South Carolina.

- c/n 2702 - C-39A (

Notable appearances in media

The DC-2 was the "Good Ship Lollipop" that Shirley Temple sang about in the film Bright Eyes (1934).[59] A DC-2 appears in the 1937 film Lost Horizon; the footage includes taxiing, takeoff, and landing, as well as views in flight.[60]

In the 1956 film Back from Eternity, the action centers on the passengers and crew of a DC-2, registry number N39165, which makes an emergency landing in headhunter territory in the remote South American jungle.[61] The plane, Construction Number (C/N) 1404, survives today (see #Surviving aircraft) in the color scheme of the one operated by KLM when it came second in the MacRobertson Air Race in 1934, flying a DC-2 registered in the Netherlands as PH-AJU Uiver.[62] The real PH-AJU was lost in a crash a few months after the MacRobertson Air Race.

Author Ernest K. Gann recounts his early days as a commercial pilot flying DC-2s in his memoir Fate Is the Hunter. This includes a particularly harrowing account of flying a DC-2 with heavy ice.

Specifications (DC-2)

Data from McDonnell Douglas aircraft since 1920 : Volume I[63]

General characteristics

- Crew: two-three

- Capacity: 14 passengers

- Length: 61 ft 11.75 in (18.8913 m)

- Wingspan: 85 ft 0 in (25.91 m)

- Height: 16 ft 3.75 in (4.9721 m)

- Wing area: 939 sq ft (87.2 m2)

- Airfoil: root: NACA 2215; tip: NACA 2209[64]

- Empty weight: 12,408 lb (5,628 kg)

- Gross weight: 18,560 lb (8,419 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Wright GR-1820-F52 Cyclone9-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engine, 775 hp (578 kW) each

- Propellers: 3-bladed variable-pitch metal propellers

Performance

- Maximum speed: 210 mph (340 km/h, 180 kn) at 8,000 ft (2,400 m)

- Cruise speed: 190 mph (310 km/h, 170 kn) at 8,000 ft (2,400 m)

- Range: 1,000 mi (1,600 km, 870 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 22,450 ft (6,840 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,000 ft/min (5.1 m/s)

- Wing loading: 19.8 lb/sq ft (97 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 0.082 hp/lb (0.135 kW/kg)

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

- List of aircraft of World War II

- List of civil aircraft

- List of military aircraft of the United States

- List of United States Navy aircraft designations (pre-1962)

References

Notes

- ISBN 9780954311568.

- ^ a b O'Leary, Michael. "Douglas Commercial Two." Air Classics magazine, May 2003.

- ^ "Douglas tells secrets of speed." Popular Mechanics, February 1935.

- ^ "DC-2 Commercial History." Archived November 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Boeing. Retrieved: November 26, 2010. Boeing.com

- ^ Francillon 1979, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Francillon 1979, p. 181.

- ^ "Air Corps flagship is flying headquarters." Popular Mechanics, January 1936.

- ^ Francillon 1979, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Francillon 1979, p. 182.

- ^ Francillon 1979, pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b Francillon 1979, p. 239.

- ^ "Phoenix Airlines". Aviation Safety. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Transportes Navales." histarmar.com. Retrieved: August 5, 2010.

- ^ R. Stocchetti. "Douglas DC2 - DC3, Aerei militari, Schede tecniche aerei militari italiani e storia degli aviatori". Archived from the original on 2015-07-13. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

- ^ Francillon 1970, p. 499.

- ^ "11-III-1935." Archived 2013-12-19 at the Wayback Machine Llega a Barajas el primer Douglas DC-2 para las Líneas Aéreas Postales Españolas (LAPE). Retrieved: February 11, 2014.

- ^ "De Uiver verongelukt bij Rutbah Wells (Irak)" (in Dutch). aviacrash.nl. Retrieved: December 6, 2011.

- ^ "Major Airline Disasters: Involving Commercial Passenger Airlines 1920-2011". airdisasters.co.uk. Retrieved: February 22, 2013.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- ^ "Major Airline Disasters: Involving Commercial Passenger Airlines." airdisasters.co.uk. Retrieved: February 22, 2013.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2017-01-21.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2017-01-21.

- ^ "The Pittsburgh Press - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2017-01-21.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- ^ Gregory Crouch (2012). "Chapter 13: The Kweilin Incident". China's Wings: War, Intrigue, Romance and Adventure in the Middle Kingdom during the Golden Age of Flight. Bantam Books. pp. 155–170 (In EPub version 3.1: pp. 172–189).

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2017-01-21.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2012-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- ^ Gregory Crouch (2012). "Chapter 17: Ventricular Tachycardia". China's Wings: War, Intrigue, Romance and Adventure in the Middle Kingdom during the Golden Age of Flight. Bantam Books. pp. 217–220. (In EPub version 3.1: pp. 240–242)

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2017-01-23.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2017-01-23.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2017-01-23.

- ^ "Major Airline Disasters: Involving Commercial Passenger Airlines 1920-2011." airdisasters.co.uk. Retrieved: February 22, 2013.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2017-01-23.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2017-01-23.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2014-09-11.

- ^ "Douglas DC-2." adf-serials.com. Retrieved: November 27, 2010.

- ^ a b "Collectieoverzicht:A–F." Aviodrome. Retrieved: November 23, 2010.

- ^ "Aerial Visuals - Airframe Photo Viewer".

- ^ "DC-2." The Australian National Aviation Museum. Retrieved: August 5, 2010.

- ^ "Hanssin-Jukka". www.hanssinjukka.fi.

- ^ "DC-2." Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine Finnish Aviation Museum. Retrieved: August 5, 2010.

- ^ "Accident description, February 7, 1951." aviation-safety.net. Retrieved: August 5, 2010.

- ^ "Douglas DC-2-118B." airliners.net. Retrieved: December 6, 2011.

- ^ "Factsheet: Douglas C-39." Archived September 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, November 30, 2007. Retrieved: October 19, 2011.

- ^ "Aircraft 38-0515 Data". Airport-Data.com. Airport-Data.com. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Boyes, Laura. "Bright Eyes (1934)". Moviediva. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Photo Documentary section of the Special Features on the 1998 Columbia/Sony DVD release of the restored version.

- ^ "Aircraft N39165 Data". Airport-Data.com. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ISBN 0870214284.

- ^ Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

- Francillon, René J. Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War. London: Putnam, 1970. ISBN 0-370-00033-1.

- Francillon, René J. McDonnell Douglas Aircraft since 1920. London: Putnam, 1979. ISBN 0-370-00050-1.

- Serrano, José Luis González (March–April 1999). "Fifty Years of DC Service: Douglas Transports Used by the Spanish Air Force". Air Enthusiast (80): 61–71. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Slieker, Hans (1984). "Talkback". ISSN 0143-5450.

- United States Air Force Museum Guidebook. Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio: Air Force Museum Foundation, 1975.

External links

- Boeing: Historical Snapshot: DC-2 Commercial Transport

- nationalmuseum.af.mil

- DC-2 Article

- Centennial of Flight Commission on DC-1 and -2

- DC-2 (cigarette cards)

- Dc-2 Images

- Dc-2 Text and Images (Russian)

- "Flying Office Saves Time of Busy Executives," Popular Mechanics, April 1935, private business version of DC-2

- Handbook of Instructions for the Maintenance of the Model DC2-120 Douglas Transport