Respiratory droplet

A respiratory droplet is a small aqueous droplet produced by exhalation, consisting of saliva or mucus and other matter derived from respiratory tract surfaces. Respiratory droplets are produced naturally as a result of breathing, speaking, sneezing, coughing, or vomiting, so they are always present in our breath, but speaking and coughing increase their number.[1][2][3]

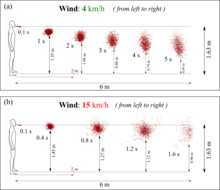

Droplet sizes range from < 1 µm to 1000 µm,[1][2] and in typical breath there are around 100 droplets per litre of breath. So for a breathing rate of 10 litres per minute this means roughly 1000 droplets per minute, the vast majority of which are a few micrometres across or smaller.[1][2] As these droplets are suspended in air, they are all by definition aerosols. However, large droplets (larger than about 100 µm, but depending on conditions) rapidly fall to the ground or another surface and so are only briefly suspended, while droplets much smaller than 100 µm (which is most of them) fall only slowly and so form aerosols with lifetimes of minutes or more, or at intermediate size, may initially travel like aerosols but at a distance fall to the ground like droplets ("jet riders").[4]

These droplets can contain infectious bacterial

Description

Respiratory droplets from humans include various cells types (e.g.

Droplets that dry in the air become

The traditional hard size cutoff of 5

Formation

Respiratory droplets can be produced in many ways. They can be produced naturally as a result of breathing, talking, sneezing, coughing, or singing. They can also be artificially generated in a healthcare setting through aerosol-generating procedures such as intubation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), bronchoscopy, surgery, and autopsy.[6] Similar droplets may be formed through vomiting, flushing toilets, wet-cleaning surfaces, showering or using tap water, or spraying graywater for agricultural purposes.[8]

Depending on the method of formation, respiratory droplets may also contain salts, cells, and virus particles.[6] In the case of naturally produced droplets, they can originate from different locations in the respiratory tract, which may affect their content.[8] There may also be differences between healthy and diseased individuals in their mucus content, quantity, and viscosity that affects droplet formation.[9]

Transport

Different methods of formation create droplets of different size and initial speed, which affect their transport and fate in the air. As described by the Wells curve, the largest droplets fall sufficiently fast that they usually settle to the ground or another surface before drying out, and droplets smaller than 100 μm will rapidly dry out, before settling on a surface.[6][8] Once dry, they become solid droplet nuclei consisting of the non-volatile matter initially in the droplet. Respiratory droplets can also interact with other particles of non-biological origin in the air, which are more numerous than them.[8] When people are in close contact, liquid droplets produced by one person may be inhaled by another person; droplets larger than 10 μm tend to remain trapped in the nose and throat while smaller droplets will penetrate to the lower respiratory system.[9]

Advanced

Role in disease transmission

A common form of

Viruses spread by droplet transmission include

Ambient temperature and humidity affect the survivability of bioaerosols because as the droplet evaporates and becomes smaller, it provides less protection for the infectious agents it may contain. In general, viruses with a lipid envelope are more stable in dry air, while those without an envelope are more stable in moist air. Viruses are also generally more stable at low air temperatures.[8]

Measures taken to reduce transmission

In a healthcare setting, precautions include housing a patient in an individual room, limiting their transport outside the room and using proper personal protective equipment.[17][18] It has been noted that during the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak, use of surgical masks and N95 respirators tended to decrease infections of healthcare workers.[19] However, surgical masks are much less good at filtering out small droplets/particles than N95 and similar respirators, so the respirators offer greater protection.[20][21]

Also, higher ventilation rates can be used as a hazard control to dilute and remove respiratory particles. However, if unfiltered or insufficiently filtered air is exhausted to another location, it can lead to spreading of an infection.[8]

History

German bacteriologist Carl Flügge in 1899 was the first to show that microorganisms in droplets expelled from the respiratory tract are a means of disease transmission. In the early 20th century, the term Flügge droplet was sometimes used for particles that are large enough to not completely dry out, roughly those larger than 100 μm.[22]

Flügge's concept of droplets as primary source and vector for respiratory transmission of diseases prevailed into the 1930s until William F. Wells differentiated between large and small droplets.[11][23] He developed the Wells curve, which describes how the size of respiratory droplets influences their fate and thus their ability to transmit disease.[24]

See also

References

- ^ ISSN 0021-8502.

- ^ S2CID 233353106.

- ^ S2CID 225114407.

- PMID 34642190.

- S2CID 221178291.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-4-154785-7.

- )

- ^ S2CID 36940738.

- ^ PMID 21094184.

- ^ PMID 32574229.

- ^ .

- ^ "Clinical Educators Guide for the prevention and control of infection in healthcare". Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. 2010. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-05. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- ^ PMID 23771256.

- ^ a b c "FAQ: Methods of Disease Transmission". Mount Sinai Hospital (Toronto). Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- S2CID 212752423.

- ^ "Pass the message: Five steps to kicking out coronavirus". World Health Organization. 2020-02-23. Retrieved 2020-03-24.

- ^ "Transmission-Based Precautions". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016-01-07. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ "Prevention of hospital-acquired infections" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). p. 45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2020.

- PMID 15761412.

- ^ "N95 Respirators and Surgical Masks (Face Masks)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2020-03-11. Retrieved 2020-03-28.

- PMID 32329337.

- PMID 14130877.

- PMID 32215590.

- ISBN 978-92-4-154785-7.