Peptic ulcer disease

| Peptic ulcer disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Peptic ulcer, stomach ulcer, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer |

| Frequency | 87.4 million (2015)[5] |

| Deaths | 267,500 (2015)[6] |

Peptic ulcer disease is a break in the inner

Common causes include the bacteria

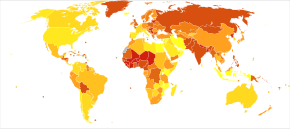

Peptic ulcers are present in around 4% of the population.[1] New ulcers were found in around 87.4 million people worldwide during 2015.[5] About 10% of people develop a peptic ulcer at some point in their life.[10] Peptic ulcers resulted in 267,500 deaths in 2015, down from 327,000 in 1990.[6][11] The first description of a perforated peptic ulcer was in 1670, in Princess Henrietta of England.[2] H. pylori was first identified as causing peptic ulcers by Barry Marshall and Robin Warren in the late 20th century,[4] a discovery for which they received the Nobel Prize in 2005.[12]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of a peptic ulcer can include one or more of the following:[citation needed]

- epigastric, strongly correlated with mealtimes. In case of duodenal ulcers, the pain appears about three hours after taking a meal and wakes the person from sleep;

- bloating and abdominal fullness;

- waterbrash (a rush of saliva after an episode of regurgitation to dilute the acid in esophagus, although this is more associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease);

- nausea and copious vomiting;

- loss of appetite and weight loss, in gastric ulcer;

- weight gain, in duodenal ulcer, as the pain is relieved by eating;

- hematemesis (vomiting of blood); this can occur due to bleeding directly from a gastric ulcer or from damage to the esophagus from severe/continuing vomiting.

- oxidized iron from hemoglobin);

- rarely, an ulcer can lead to a gastric or acute peritonitis and extreme, stabbing pain,[13]and requires immediate surgery.

A history of

In people over the age of 45 with more than two weeks of the above symptoms, the odds for peptic ulceration are high enough to warrant rapid investigation by esophagogastroduodenoscopy.[citation needed]

The timing of symptoms in relation to the meal may differentiate between gastric and duodenal ulcers. A gastric ulcer would give epigastric pain during the meal, associated with nausea and vomiting, as gastric acid production is increased as food enters the stomach. Pain in duodenal ulcers would be aggravated by hunger and relieved by a meal and is associated with night pain.[14]

Also, the symptoms of peptic ulcers may vary with the location of the ulcer and the person's age. Furthermore, typical ulcers tend to heal and recur, and as a result the pain may occur for few days and weeks and then wane or disappear.

A burning or gnawing feeling in the stomach area lasting between 30 minutes and 3 hours commonly accompanies ulcers. This pain can be misinterpreted as

Complications

- Gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common complication. Sudden large bleeding can be life-threatening.[18][19] It is associated with 5% to 10% death rate.[14]

- Perforation (a hole in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract) following a gastric ulcer often leads to catastrophic consequences if left untreated. Erosion of the gastrointestinal wall by the ulcer leads to spillage of the stomach or intestinal contents into the abdominal cavity, leading to an acute chemical peritonitis.[20] The first sign is often sudden intense abdominal pain,[14] as seen in Valentino's syndrome. Posterior gastric wall perforation may lead to bleeding due to the involvement of gastroduodenal artery that lies posterior to the first part of the duodenum.[citation needed] The death rate in this case is 20%.[14]

- Penetration is a form of perforation in which the hole leads to and the ulcer continues into adjacent organs such as the liver and pancreas.[15]

- Gastric outlet obstruction (stenosis) is a narrowing of the pyloric canal by scarring and swelling of the gastric antrum and duodenum due to peptic ulcers. The person often presents with severe vomiting.[14]

- Cancer is included in the differential diagnosis (elucidated by biopsy), Helicobacter pylori as the etiological factor making it 3 to 6 times more likely to develop stomach cancer from the ulcer.[15] The risk for developing gastrointestinal cancer also appears to be slightly higher with gastric ulcers.[21]

Cause

H. pylori

Human immune response toward the bacteria also determines the emergence of peptic ulcer disease. The human IL1B gene encodes for

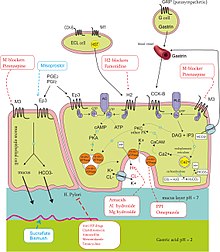

NSAIDs

Taking

Stress

Stress due to serious health problems, such as those requiring treatment in an intensive care unit, is well described as a cause of peptic ulcers, which are also known as stress ulcers.[3]

While chronic life stress was once believed to be the main cause of ulcers, this is no longer the case.[23] It is, however, still occasionally believed to play a role.[23] This may be due to the well-documented effects of stress on gastric physiology, increasing the risk in those with other causes, such as H. pylori or NSAID use.[24]

Diet

Dietary factors, such as spice consumption, were hypothesized to cause ulcers until the late 20th century, but have been shown to be of relatively minor importance.[25] Caffeine and coffee, also commonly thought to cause or exacerbate ulcers, appear to have little effect.[26][27] Similarly, while studies have found that alcohol consumption increases risk when associated with H. pylori infection, it does not seem to independently increase risk. Even when coupled with H. pylori infection, the increase is modest in comparison to the primary risk factor.[28][29][nb 1]

Other

Other causes of peptic ulcer disease include gastric

It is still unclear whether smoking increases the risk of getting peptic ulcers.[14]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is mainly established based on the characteristic symptoms. Stomach pain is usually the first signal of a peptic ulcer. In some cases, doctors may treat ulcers without diagnosing them with specific tests and observe whether the symptoms resolve, thus indicating that their primary diagnosis was accurate.[citation needed]

More specifically, peptic ulcers erode the muscularis mucosae, at minimum reaching to the level of the submucosa (contrast with erosions, which do not involve the muscularis mucosae).[31]

Confirmation of the diagnosis is made with the help of tests such as endoscopies or barium contrast x-rays. The tests are typically ordered if the symptoms do not resolve after a few weeks of treatment, or when they first appear in a person who is over age 45 or who has other symptoms such as weight loss, because stomach cancer can cause similar symptoms. Also, when severe ulcers resist treatment, particularly if a person has several ulcers or the ulcers are in unusual places, a doctor may suspect an underlying condition that causes the stomach to overproduce acid.[15]

An

One of the reasons that

The diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori can be made by:

- Urea breath test (noninvasive and does not require EGD);

- Direct culture from an EGD biopsy specimen; this is difficult and can be expensive. Most labs are not set up to perform H. pylori cultures;

- Direct detection of urease activity in a biopsy specimen by rapid urease test;[14]

- Measurement of antibody levels in the blood (does not require EGD). It is still somewhat controversial whether a positive antibody without EGD is enough to warrant eradication therapy;

- Stool antigen test;[33]

- Histological examination and staining of an EGD biopsy.

The breath test uses radioactive carbon to detect H. pylori.[34] To perform this exam, the person is asked to drink a tasteless liquid that contains the carbon as part of the substance that the bacteria breaks down. After an hour, the person is asked to blow into a sealed bag. If the person is infected with H. pylori, the breath sample will contain radioactive carbon dioxide. This test provides the advantage of being able to monitor the response to treatment used to kill the bacteria.

The possibility of other causes of ulcers, notably

If a peptic ulcer perforates, air will leak from inside the gastrointestinal tract (which always contains some air) to the peritoneal cavity (which normally never contains air). This leads to "free gas" within the peritoneal cavity. If the person stands, as when having a chest X-ray, the gas will float to a position underneath the diaphragm. Therefore, gas in the peritoneal cavity, shown on an erect chest X-ray or supine lateral abdominal X-ray, is an omen of perforated peptic ulcer disease.

Classification

- Esophagus

- Stomach

- Ulcers

- Duodenum

- Mucosa

- Submucosa

- Muscle

Peptic ulcers are a form of acid–peptic disorder. Peptic ulcers can be classified according to their location and other factors.

By location

- Duodenum (called duodenal ulcer)

- Esophagus (called esophageal ulcer)

- Stomach (called gastric ulcer)

- Meckel's diverticulum (called Meckel's diverticulum ulcer; is very tender with palpation)

Modified Johnson

- Type I: Ulcer along the body of the stomach, most often along the lesser curve at incisura angularis along the locus minoris resistantiae. Not associated with acid hypersecretion.

- Type II: Ulcer in the body in combination with duodenal ulcers. Associated with acid oversecretion.

- Type III: In the pyloric channel within 3 cm of pylorus. Associated with acid oversecretion.

- Type IV: Proximal gastroesophageal ulcer.

- Type V: Can occur throughout the stomach. Associated with the chronic use of NSAIDs (such as ibuprofen).

Macroscopic appearance

Gastric ulcers are most often localized on the lesser curvature of the stomach. The ulcer is a round to oval parietal defect ("hole"), 2–4 cm diameter, with a smooth base and perpendicular borders. These borders are not elevated or irregular in the acute form of peptic ulcer, and regular but with elevated borders and inflammatory surrounding in the chronic form. In the ulcerative form of gastric cancer, the borders are irregular. Surrounding mucosa may present radial folds, as a consequence of the parietal scarring.[citation needed]

Microscopic appearance

A gastric peptic ulcer is a mucosal perforation that penetrates the muscularis mucosae and lamina propria, usually produced by acid-pepsin aggression. Ulcer margins are perpendicular and present chronic gastritis. During the active phase, the base of the ulcer shows four zones: fibrinoid necrosis, inflammatory exudate, granulation tissue and fibrous tissue. The fibrous base of the ulcer may contain vessels with thickened wall or with thrombosis.[35]

Differential diagnosis

Conditions that may appear similar include:

Prevention

Prevention of peptic ulcer disease for those who are taking NSAIDs (with low cardiovascular risk) can be achieved by adding a

Management

Eradication therapy

Once the diagnosis of H. pylori is confirmed, the first-line treatment would be a triple regimen in which pantoprazole and clarithromycin are combined with either amoxicillin or metronidazole. This treatment regimen can be given for 7–14 days. However, its effectiveness in eradicating H. pylori has been reducing from 90% to 70%. However, the rate of eradication can be increased by doubling the dosage of pantoprazole or increasing the duration of treatment to 14 days. Quadruple therapy (pantoprazole, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and metronidazole) can also be used. The quadruple therapy can achieve an eradication rate of 90%. If the clarithromycin resistance rate is higher than 15% in an area, the usage of clarithromycin should be abandoned. Instead, bismuth-containing quadruple therapy can be used (pantoprazole, bismuth citrate, tetracycline, and metronidazole) for 14 days. The bismuth therapy can also achieve an eradication rate of 90% and can be used as second-line therapy when the first-line triple-regimen therapy has failed.

NSAIDs-induced ulcers

NSAID-associated ulcers heal in six to eight weeks provided the NSAIDs are withdrawn with the introduction of

Bleeding

For those with bleeding peptic ulcers,

Early endoscopic therapy can help to stop bleeding by using

For those with

Anticoagulants

According to expert opinion, for those who are already on anticoagulants, the

Epidemiology

The lifetime risk for developing a peptic ulcer is approximately 5% to 10%[10][14] with the rate of 0.1% to 0.3% per year.[14] Peptic ulcers resulted in 301,000 deaths in 2013, down from 327,000 in 1990.[11]

In Western countries, the percentage of people with H. pylori infections roughly matches age (i.e., 20% at age 20, 30% at age 30, 80% at age 80, etc.). Prevalence is higher in third world countries, where it is estimated at 70% of the population, whereas developed countries show a maximum of a 40% ratio. Overall, H. pylori infections show a worldwide decrease, more so in developed countries. Transmission occurs via food, contaminated groundwater, or human saliva (such as from kissing or sharing food utensils).[37]

Peptic ulcer disease had a tremendous effect on morbidity and mortality until the last decades of the 20th century when epidemiological trends started to point to an impressive fall in its incidence. The reason that the rates of peptic ulcer disease decreased is thought to be the development of new effective medication and acid suppressants and the rational use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[14]

History

The H. pylori hypothesis was still poorly received,

In 1997, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with other government agencies, academic institutions, and industry, launched a national education campaign to inform health care providers and consumers about the link between H. pylori and ulcers. This campaign reinforced the news that ulcers are a curable infection and that health can be greatly improved and money saved by disseminating information about H. pylori.[43]

In 2005, the

Some believed that

Notes

- ^ Sonnenberg in his study cautiously concludes that, among other potential factors that were found to correlate to ulcer healing, "moderate alcohol intake might [also] favor ulcer healing." (p. 1066)

References

- ^ PMID 21872087.

- ^ S2CID 25464311.

- ^ PMID 12072662.

- ^ PMID 21944414.

- ^ PMID 27733282.)

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 27733281.

- ^ "Definition and Facts for Peptic Ulcer Disease". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ISBN 9788131238714.

- ^ "Eating, Diet, and Nutrition for Peptic Ulcer Disease". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ PMID 18837773.

- ^ PMID 25530442.)

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2005". nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ISBN 9789350259443.

- ^ S2CID 4547048.

- ^ a b c d "Peptic Ulcer". Home Health Handbook for Patients & Caregivers. Merck Manuals. October 2006. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011.

- ^ "Peptic ulcer". Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "Ulcer Disease Facts and Myths". Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- PMID 9391242.

- .

- PMID 30137838.

- PMID 26923747.

- S2CID 24654342. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ S2CID 30231594.

- S2CID 42592868.

- ^ For nearly 100 years, scientists and doctors thought that ulcers were caused by stress, spicy food, and alcohol. Treatment involved bed rest and a bland diet. Later, researchers added stomach acid to the list of causes and began treating ulcers with antacids. National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse Archived 5 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- PMID 15171675.

- ISBN 978-1-60547-968-2.

- PMID 17589905.

- PMID 7026344.

- PMID 25905301.

- ^ "Peptic Ulcer Disease". Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ "Peptic ulcer". Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- PMID 18704207.

- ^ "Tests and diagnosis". Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "ATLAS OF PATHOLOGY". Archived from the original on 9 February 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- PMID 11218379.

- ISBN 978-0-86793-035-1. Archivedfrom the original on 21 May 2016.

- S2CID 1641856.

- S2CID 10066001.

- ^ Schulz K (9 September 2010). "Stress Doesn't Cause Ulcers! Or, How To Win a Nobel Prize in One Easy Lesson: Barry Marshall on Being ... Right". The Wrong Stuff. Slate. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- from the original on 27 June 2009.

- ^ "Ulcer, Diagnosis and Treatment - CDC Bacterial, Mycotic Diseases". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- PMID 9874617. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. See also their corrections in the next volume Archived 5 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- PMID 12562704.

- PMID 12888582.

External links

- Gastric ulcer images

- "Peptic Ulcer". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.