Dur-Sharrukin

ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ (in Syriac) دور شروكين (in Arabic) | |

Khorsabad, Nineveh Governorate, Iraq | |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°30′34″N 43°13′46″E / 36.50944°N 43.22944°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Length | 1,760 m (5,770 ft) |

| Width | 1,635 m (5,364 ft) |

| Area | 2.88 km2 (1.11 sq mi) |

| History | |

| Founded | In the decade preceding 706 BC |

| Abandoned | Approximately 605 BC |

| Periods | Neo-Assyrian Empire |

| Cultures | Assyrian |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1842–1844, 1852–1855 1928–1935, 1957 |

| Archaeologists | Paul-Émile Botta, Eugène Flandin, Victor Place, Edward Chiera, Gordon Loud, Hamilton Darby, Fuad Safar |

| Condition | Severely Damaged |

| Public access | Inaccessible |

Dur-Sharrukin ("Fortress of Sargon";

History

Sargon II ruled from 722 to 705 BC. The demands for timber and other materials and craftsmen, who came from as far as coastal Phoenicia, are documented in contemporary Assyrian letters. The debts of construction workers were nullified in order to attract a sufficient labour force. The land in the environs of the town was taken under cultivation, and olive groves were planted to increase Assyria's deficient oil-production. The great city was entirely built in the decade preceding 706 BC, when the court moved to Dur-Sharrukin, although it was not completely finished yet. Sargon was killed during a battle in 705. After his unexpected death his son and successor Sennacherib abandoned the project, and relocated the capital with its administration to the city of Nineveh, 20 km south. The city was never completed and it was finally abandoned a century later when the Assyrian empire fell.[1]

Destruction by ISIL

On 8 March 2015 the

Description

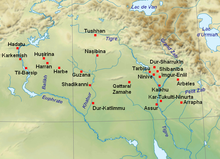

The town was of rectangular layout and measured 1758.6 by 1635 metres. The enclosed area comprised 3 square kilometres, or 288 hectares. The length of the walls was 16280 Assyrian units, which according to Sargon himself corresponded to the numerical value of his name.

In the south-west corner of the city was located a secondary citadel, used as a control point against internal riots and foreign invasions.

On the central canal of Sargon's garden stood a pillared pleasure-pavilion which looked up to a great topographic creation: a man-made Garden Mound. This Mound was planted with cedars and cypresses and was modelled after a foreign landscape, the Amanus mountains in north Syria, which had so amazed the Assyrian kings. In their flat palace-gardens they built a replica of what they had encountered.[9]

Archaeology

Dur-Sharrukin is roughly a square with a border marked by a city wall 24 meters thick with a stone foundation pierced by seven massive gates. A mound in the north-east section marks the location of the palace of Sargon II. At the time of its construction, the village on the site was named Maganuba. [10]

Early Excavations

While Dur-Sharrukin was abandoned in antiquity and thus did not attract the same level of attention as other ancient Assyrian sites, there was some awareness of the origins of the mound well before European excavation. For instance, the medieval Arab geographer

"The small party employed by M. Botta were at work on Kouyunjik, when a peasant from a distant village chanced to visit the spot. Seeing that every fragment of brick and alabaster uncovered by the workmen was carefully preserved, he asked the reason of this, to him, strange proceeding. On being informed that they were in search of sculptured stones, he advised them to try the mound on which his village was built, and in which, he declared, many such things as they wanted had been exposed on digging for the foundations of new houses. M. Botta, having been frequently deceived by similar stories, was not at first inclined to follow the peasant's advice, but subsequently sent an agent and one or two workmen to the place. After a little opposition from the inhabitants, they were permitted to sink a well in the mound; and at a small distance from the surface they came to the top of a wall which, on digging deeper, they found to be built of sculptured slabs of gypsum. M. Botta, on receiving information of this discovery, went at once to the village, which was called Khorsabad. He directed a wider trench to be formed, and to be carried in the direction of the wall. He soon found that he had entered a chamber, connected with others, and surrounded by slabs of gypsum covered with sculptured representations of battles, sieges, and similar events. His wonder may easily be imagined. A new history had been suddenly opened to him-the records of an unknown people were before him." [14]

The interplay between local mediators and European archaeologists in Layard's account effectively captures the necessary cooperation which enabled these early discoveries. With this initial excavation, the archaeological investigation of ancient Mesopotamia began in earnest. Unlike

The Qurnah Disaster

By 1852, excavations of the site had been resumed by the new French consul, Victor Place, and in 1855 another shipment of antiquities was ready to be sent back to Paris.[23][24] A cargo ship and four rafts were prepared to carry the artifacts, but even this substantial effort was over-whelmed by the sheer number of items to be transported. Additionally, shortly after the convoy reached Baghdad, Place was summoned to his new consular post in Moldavia due to the ongoing Crimean War, and had to leave the shipment in the hands of a French schoolteacher, M. Clement to finalise its return to Paris.[25][26]

More antiquities from Rawlinson's expedition to Kuyunjik and Fresnel's to Babylon were also added to the shipment.[27] The troubles began once the convoy left Baghdad in May 1855, as the banks of the river Tigris were controlled by local sheikhs who were hostile to the Ottoman authorities and frequently raided shipping sailing by.[28] During the journey, the convoy was boarded several times, forcing the crew to relinquish most of their money and supplies in order to be allowed further passage on the river.[25][27]

Once the convoy reached Al-Qurnah (Kurnah) it was assaulted by local pirates led by Sheikh Abu Saad, whose actions sank the main cargo ship and forced the four rafts aground shortly afterwards.[27] The entire shipment was almost completely lost with only 28 of over 200 crates eventually making it to the Louvre in Paris.[29][30] Subsequent efforts to recover the lost antiquities, including a Japanese expedition in 1971-2, have largely been unsuccessful.[27][31]

20th Century Excavations

The site of Khorsabad was excavated between 1928–1935 by American archaeologists from the

In 1957, archaeologists from the Iraqi Department Antiquities, led by Fuad Safar excavated at the site, uncovering the temple of Sibitti.[33]

Gallery

-

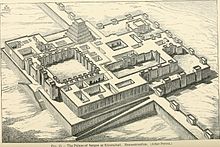

Plan of Dur-Sharrukin, 1867

-

The Timber Transportation relief at the Louvre

-

Khorsabad brick, Assyria. Babylonian; Louvre Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection

-

Palace of Dur-Sharrukin

-

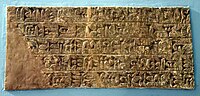

Dur-Sharrukin foundation cylinder

-

Sargon II (left) faces a high-ranking official, possibly Sennacherib his son and crown prince. 710-705 BCE. From Khorsabad, Iraq. The British Museum, London

-

Part of a door-sill from Khorsabad, describing the construction of Sargon II's palace, the British Museum

-

Tributary scene from the Royal Palace at Khorsabad, Iraq. The Iraq Museum

-

Assyrian attendants carrying the throne of Sargon II, part of a tributary scene from Khorsabad, Iraq. Iraq Museum

-

Sargon II in his royal chariot, tramping a dead or dying enemy, part of a war scene from Khorsabad, Iraq. The Iraq Museum

-

Assyrian human-headed protective spirit from Khorsabad, Iraq. The Iraq Museum

-

A horse and an Assyrian groom, from Khorsabad, Iraq. Iraq Museum

-

Assyrian archers attacking a city. From Khorsabad, Iraq. The Iraq Museum

-

1853 excavation of the gate of Sargon's palace

See also

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- Destruction of cultural heritage by ISIL

- Short chronology timeline

- List of megalithic sites

Notes

- ISBN 1-4051-4911-6

- ^ a b "Ancient site Khorsabad attacked by Islamic State: reports". Toronto Star. 8 March 2015. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives مبادرات التراث الثقافي". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- ^ Fuchs, Die Inschriften Sargons II. aus Khorsabad, 42:65; 294f. See the discussion by Eckart Frahm, "Observations on the Name and Age of Sargon II and on Some Patterns of Assyrian Royal Onomastics," NABU 2005-2.44 Archived 2016-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ISBN 978-1146066846.

- Neo-Hittitekingdoms.

- ^ D.D. Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, vol II:242, quoted in Robin Lane Fox, Travelling Heroes in the Epic Age of Homer 2008, pp26f.

- ^ Lane Fox 2008:27; texts are in Luckenbill 1927:II.

- ^ Lane Fox 2008:27, noting D. Stronach, "The Garden as a political statement: some case-studies from the Near East in the first millennium BC", Bulletin of the Asia Institute 4 (1990:171-80). The garden mount first documented at Dur-Sharrukin was to have a long career in the history of gardening.

- ^ Cultraro M., Gabellone F., Scardozzi G, Integrated Methodologies and Technologies for the Reconstructive Study of Dur-Sharrukin (Iraq), XXI International CIPA Symposium, 2007

- ^ Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains, Vol. I, 2nd ed. (London: John Murray, 1849), 149.

- ^ Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains, 149.

- ^ Mogens Trolle Larsen, The Conquest of Assyria: Excavations in an Antique Land (New York: Routledge, 1996), pp. 12-3.

- ^ Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains, pp. 10-1.

- ^ Larsen, Conquest of Assyria, 23-4.

- ^ Zainab Bahrani, Zeynep Çelik, and Edhem Eldem, Scramble for the Past: A Story of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire, 1753-1914, (Istanbul: SALT, 2011), 132-4.

- ^ Paul Emile Botta and Eugene Flandin, Monument de Ninive, in 5 volumes, Imprimerie nationale, 1946-50

- ^ E. Guralnick, New drawings of Khorsabad sculptures by Paul Émile Botta, Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale, vol. 95, pp. 23-56, 2002

- ^ Larsen, Conquest of Assyria, 26-30

- ^ During his visit several years later, Layard reports that "the place is consequently very unhealthy, and the few squalid inhabitants who appeared, were almost speechless from ague. During M. Botta's excavations, the workmen suffered greatly from fever, and many fell victims to it." See Layard, Nineveh and its Remains, 148.

- ^ Carine Harmand, "Sparking the imagination: the rediscovery of Assyria's great lost city," (February 1, 2019), https://blog.britishmuseum.org/sparking-the-imagination-the-rediscovery-of-assyrias-great-lost-city/ Archived 2021-01-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Larsen, Conquest of Assyria, 32.

- ^ Victor Place, Nineve et l'Assyie, in 3 volumes, Imprimerie impériale, 1867–1879

- ISBN 1-59333-067-7)

- ^ pp. 344-9

- ^ Potts, D. T. "Potts 2020. 'Un coup terrible de la fortune:' A. Clément and the Qurna disaster of 1855. Pp. 235-244 in Finkel, I.L. and Simpson, St J., eds. In Context: The Reade Festschrift. Oxford: Archaeopress". Archived from the original on 2021-04-11. Retrieved 2021-04-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d [1]Namio Egami, "The Report of The Japan Mission For The Survey of Under-Water Antiquities At Qurnah: The First Season," (1971-72), 1-45

- ^ Pillet, Maurice (1881-1964) Auteur du texte (1922). L'expédition scientifique et artistique de Mésopotamie et de Médie, 1851-1855 / Maurice Pillet,... Archived from the original on 2021-04-11. Retrieved 2021-04-11.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Samuel D. Pfister, "The Qurnah Disaster: Archaeology & Piracy in Mesopotamia," Bible History Daily, (January 20, 2021), https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/the-qurnah-disaster/ Archived 2021-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Robert William Rogers, A history of Babylonia and Assyria: Volume 1, Abingdon Press, 1915

- ISSN 1356-1863.

- ^ [2] Archived 2010-06-18 at the Wayback Machine OIC 16. Tell Asmar, Khafaje and Khorsabad: Second Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition, Henri Frankfort, 1933; [3] Archived 2010-06-18 at the Wayback Machine OIC 17. Iraq Excavations of the Oriental Institute 1932/33: Third Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition, Henri Frankfort, 1934; [4] Archived 2010-06-18 at the Wayback Machine Gordon Loud, Khorsabad, Part 1: Excavations in the Palace and at a City Gate, Oriental Institute Publications 38, University of Chicago Press, 1936; [5] Archived 2010-06-18 at the Wayback Machine Gordon Loud and Charles B. Altman, Khorsabad, Part 2: The Citadel and the Town, Oriental Institute Publications 40, University of Chicago Press, 1938

- ^ F. Safar, "The Temple of Sibitti at Khorsabad", Sumer 13 (1957:219-21).

References

- Bahrani, Zainab, Zeynep Çelik, and Edhem Eldem. Scramble for the Past: A Story of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire, 1753-1914. Istanbul: SALT, 2011.

- [6] Buckingham, James Silk, The buried city of the East, Nineveh: a narrative of the discoveries of Mr. Layard and M. Botta at Nimroud and Khorsabad, National Illustrated Library, 1851

- A. Fuchs, Die Inschriften Sargons II. aus Khorsabad, Cuvillier, 1994, ISBN 3-930340-42-9

- A. Caubet, Khorsabad: le palais de Sargon II, roi d'Assyrie: Actes du colloque organisé au musée du Louvre par le Services culturel les 21 et 22 janvier 1994, La Documentation française, 1996, ISBN 2-11-003416-5

- Guralnick, Eleanor, "The Palace at Khorsabad: A Storeroom Excavation Project." In D. Kertai and P. A. Miglus (eds.) New Research on Late Assyrian Palaces. Conference at Heidelberg January 22, 2011, 5–10. Heidelberger Studien zum Alten Orient 15. Heidelberg: Heidelberger Orientverlag, 2013

- Harmand, Carine, "Sparking the Imagination: The Rediscovery of Assyria's Great Lost City." British Museum Blog. (February 1, 2019). https://blog.britishmuseum.org/sparking-the-imagination-the-rediscovery-of-assyrias-great-lost-city/.

- Larsen, Mogens Trolle. The Conquest of Assyria: Excavations in an Antique Land, 1840-1860. New York: Routledge, 1996.

- Layard, Austen Henry. Nineveh and Its Remains. Vol. I. 2nd ed. London: John Murray, 1849.

- Pfister, Samuel D. "The Qurnah Disaster: Archaeology & Piracy in Mesopotamia." Bible History Daily. (January 20, 2021). https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/the-qurnah-disaster/.

- Arno Poebel, The Assyrian King-List from Khorsabad, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 247–306, 1942

- Arno Poebel, The Assyrian King List from Khorsabad (Continued), Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 460–492, 1942

- Pauline Albenda, The palace of Sargon, King of Assyria: Monumental wall reliefs at Dur-Sharrukin, from original drawings made at the time of their discovery in 1843–1844 by Botta and Flandin, Editions Recherche sur les civilisations, 1986, ISBN 2-86538-152-8