Early human migrations

Early human migrations are the earliest migrations and expansions of archaic and modern humans across continents. They are believed to have begun approximately 2 million years ago with the early expansions out of Africa by Homo erectus. This initial migration was followed by other archaic humans including H. heidelbergensis, which lived around 500,000 years ago and was the likely ancestor of Denisovans and Neanderthals as well as modern humans. Early hominids had likely crossed land bridges that have now sunk.

Within Africa,

Early Eurasian Homo sapiens fossils have been found in Israel and Greece, dated to 194,000–177,000 and 210,000 years old respectively. These fossils seem to represent failed dispersal attempts by early Homo sapiens, who were likely replaced by local Neanderthal populations.

The migrating modern human populations are known to have

After the

Early humans (before Homo sapiens)

The

Homo erectus

Between 2 and less than a million years ago,

Key sites for this early migration out of Africa are Riwat in Pakistan (~2 Ma?[7]), Ubeidiya in the Levant (1.5 Ma) and Dmanisi in the Caucasus (1.81 ± 0.03 Ma, p=0.05[8]).

Robert G. Bednarik has suggested that Homo erectus may have built rafts and sailed oceans, a theory that has raised some controversy.[13]

After H. erectus

One million years after its dispersal, H. erectus was diverging into new species. H. erectus is a

H. heidelbergensis, Neanderthals and Denisovans expanded north beyond the

Other archaic human species are assumed to have spread throughout Africa by this time, although the fossil record is sparse. Their presence is assumed based on traces of

Neanderthals spread across the Near East and Europe, while Denisovans appear to have spread across Central and East Asia and to Southeast Asia and Oceania. There is evidence that Denisovans interbred with Neanderthals in Central Asia where their habitats overlapped.[20] Neanderthal evidence has also been found quite late at 33,000 years ago at the 65th latitude of the Byzovaya site in the Ural Mountains. This is far outside of any otherwise known habitat, during a high ice cover period, and perhaps reflects a refugia of near extinction.

Homo sapiens

Dispersal throughout Africa

In September 2019, scientists reported the computerized determination, based on 260

In July 2019, anthropologists reported the discovery of 210,000 year old remains of a H. sapiens and 170,000 year old remains of a H. neanderthalensis in Apidima Cave in southern Greece, more than 150,000 years older than previous H. sapiens finds in Europe.[30][31][32][33]

Early modern humans expanded to Western Eurasia and Central, Western and Southern Africa from the time of their emergence. While

The ancestors of the modern

Expansion to Central Africa by the ancestors of the

The situation in

Early northern Africa dispersal

Populations of Homo sapiens migrated to the Levant and to Europe[dubious ] between 130,000 and 115,000 years ago, and possibly in earlier waves as early as 185,000 years ago.[note 8]

A fragment of a jawbone with eight teeth found at Misliya Cave has been dated to around 185,000 years ago. Layers dating from between 250,000 and 140,000 years ago in the same cave contained tools of the Levallois type which could put the date of the first migration even earlier if the tools can be associated with the modern human jawbone finds.[42][43]

These early migrations do not appear to have led to lasting colonisation and receded by about 80,000 years ago.[20] There is a possibility that this first wave of expansion may have reached China (or even North America[dubious ][44]) as early as 125,000 years ago, but would have died out without leaving a trace in the genome of contemporary humans.[20]

There is some evidence that modern humans left Africa at least 125,000 years ago using two different routes: through the

Since these previous exits from Africa did not leave traces in the results of genetic analyses based on the Y chromosome and on MtDNA, it seems that those modern humans did not survive in large numbers and were assimilated by our major antecessors. An explanation for their extinction (or small genetic imprint) may be the Toba eruption (74,000 years ago), though some argue it scarcely affected human population.[57]

Coastal migration

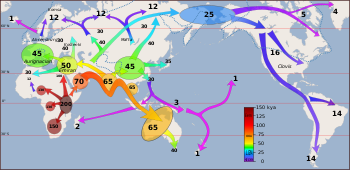

The so-called "recent dispersal" of modern humans took place about 70–50,000 years ago.[58][59][60] It is this migration wave that led to the lasting spread of modern humans throughout the world.

A small group from a population in East Africa, bearing

Along the way H. sapiens interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans,[65] with Denisovan DNA making 0.2% of mainland Asian and Native American DNA.[66]

Nearby Oceania

Migrations continued along the Asian coast to Southeast Asia and Oceania, colonising

During this time sea level was much lower and most of

Sequencing of one Aboriginal genome from an old hair sample in Western Australia revealed that the individual was descended from people who migrated into East Asia between 62,000 and 75,000 years ago. This supports the theory of a single migration into Australia and New Guinea before the arrival of Modern Asians (between 25,000 and 38,000 years ago) and their later migration into North America.[77] This migration is believed to have happened around 50,000 years ago, before Australia and New Guinea were separated by rising sea levels approximately 8,000 years ago.[78][79] This is supported by a date of 50,000–60,000 years ago for the oldest evidence of settlement in Australia,[67][80] around 40,000 years ago for the oldest human remains,[67] the earliest humans artifacts which are at least 65,000 years old[81] and the extinction of the Australian megafauna by humans between 46,000 and 15,000 years ago argued by Tim Flannery,[82] which is similar to what happened in the Americas. The continued use of Stone Age tools in Australia has been much debated.[83]

Dispersal throughout Eurasia

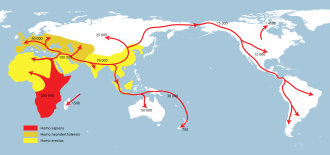

Homo erectus greatest extent (yellow),

Homo neanderthalensis greatest extent (ochre) and

Homo sapiens (red).

The population brought to the

Towards the West, Upper Paleolithic populations associated with mitochondrial haplogroup R and its derivatives, spread throughout Asia and Europe, with a back-migration of M1 to North Africa and the Horn of Africa several millennia ago. [dubious ]

Presence

There is evidence from

Europe

The recent expansion of

An important difference between Europe and other parts of the inhabited world was the northern latitude. Archaeological evidence suggests humans, whether Neanderthal or Cro-Magnon, reached sites in Arctic Russia by 40,000 years ago.[89]

Cro-Magnon are considered the first anatomically modern humans in Europe. They entered Eurasia by the Zagros Mountains (near present-day Iran and eastern Turkey) around 50,000 years ago, with one group rapidly settling coastal areas around the Indian Ocean and another migrating north to the steppes of Central Asia.[90] Modern human remains dating to 43,000–45,000 years ago have been discovered in Italy[91] and Britain,[92] as well as in the European Russian Arctic from 40,000 years ago.[89][93]

Humans colonised the environment west of the Urals, hunting reindeer especially,[94] but were faced with adaptive challenges; winter temperatures averaged from −20 to −30 °C (−4 to −22 °F) with fuel and shelter scarce. They travelled on foot and relied on hunting highly mobile herds for food. These challenges were overcome through technological innovations: tailored clothing from the pelts of fur-bearing animals; construction of shelters with hearths using bones as fuel; and digging "ice cellars" into the permafrost to store meat and bones.[94][95]

However, from recent research it is believed that the ecological crisis resulting from the eruption in c. 38,000 BC of the super-volcano in the

A mitochondrial DNA sequence of two Cro-Magnons from the Paglicci Cave in Italy, dated to 23,000 and 24,000 years old (Paglicci 52 and 12), identified the mtDNA as Haplogroup N, typical of the latter group.[100]

(YBP =

The expansion of modern human population is thought to have begun 45,000 years ago, and it may have taken 15,000–20,000 years for Europe to be colonized.[102][103]

During this time, the Neanderthals were slowly being displaced. Because it took so long for Europe to be occupied, it appears that humans and Neanderthals may have been constantly competing for territory. The Neanderthals had larger brains, and were larger overall, with a more robust or heavily built frame, which suggests that they were physically stronger than modern Homo sapiens. Having lived in Europe for 200,000 years, they would have been better adapted to the cold weather. The anatomically modern humans known as the

From the extent of linkage disequilibrium, it was estimated that the last Neanderthal gene flow into early ancestors of Europeans occurred 47,000–65,000 years BP. In conjunction with archaeological and fossil evidence, interbreeding is thought to have occurred somewhere in Western Eurasia, possibly the Middle East.[85] Studies show a higher Neanderthal admixture in East Asians than in Europeans.[105][106] North African groups share a similar excess of derived alleles with Neanderthals as non-African populations, whereas Sub-Saharan African groups are the only modern human populations with no substantial Neanderthal admixture.[note 10] The Neanderthal-linked haplotype B006 of the dystrophin gene has also been found among nomadic pastoralist groups in the Sahel and Horn of Africa, who are associated with northern populations. Consequently, the presence of this B006 haplotype on the northern and northeastern perimeter of Sub-Saharan Africa is attributed to gene flow from a non-African point of origin.[note 11]

East, Southeast and North Asia

"

A 2016 study presented an analysis of the population genetics of the

Mitochondrial haplogroups

A review paper by Melinda A. Yang (in 2022) summarized and concluded that a distinctive "Basal-East Asian population" referred to as 'East- and Southeast Asian lineage' (ESEA); which is ancestral to modern East Asians,

Last Glacial Maximum

Eurasia

Around 20,000 years ago, approximately 5,000 years after the Neanderthal extinction, the

Americas

Conventional estimates have it that humans reached North America at some point between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago.

Holocene migrations

The

This period sees the transition from the

Large-scale migrations of the Mesolithic to Neolithic era are thought to have given rise to the pre-modern distribution of the world's major

Eurasia

Evidence published in 2014 from genome analysis of ancient human remains suggests that the modern native populations of Europe largely descend from three distinct lineages: "

Sub-Saharan Africa

West-Eurasian back-migrations started in the early

The

Some evidence (including a 2016 study by Busby et al.) suggests admixture from ancient and recent migrations from Eurasia into parts of Sub-Saharan Africa.[139] Another study (Ramsay et al. 2018) also shows evidence that ancient Eurasians migrated into Africa and that Eurasian admixture in modern Sub-Saharan Africans ranges from 0% to 50%, varying by region and generally higher in the Horn of Africa and parts of the Sahel zone, and found to a lesser degree in certain parts of Western Africa, and Southern Africa (excluding recent immigrants).[140]

Indo-Pacific

The first seaborne human migrations were by the

A branch of the Austronesians reached

In the

Caribbean

The Caribbean was one of the last places in the Americas that were settled by humans. The oldest remains are known from the Greater Antilles (Cuba and Hispaniola) dating between 4000 and 3500 BCE, and comparisons between tool-technologies suggest that these peoples moved across the Yucatán Channel from Central America. All evidence suggests that later migrants from 2000 BCE and onwards originated from South America, via the Orinoco region.[146] The descendants of these migrants include the ancestors of the Taíno and Kalinago (Island Carib) peoples.[147]

Arctic

The earliest inhabitants of North America's central and eastern Arctic are referred to as the Arctic small tool tradition (AST) and existed c. 2500 BCE. AST consisted of several Paleo-Eskimo cultures, including the Independence cultures and Pre-Dorset culture.[148][149]

The

See also

- List of first human settlements

- Middle Paleolithic

- Quaternary extinction event

- Timeline of human evolution

- Timeline of maritime migration and exploration

Notes

- ^ Based on Schlebusch et al., "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago",[1] Fig. 3 (H. sapiens divergence times) and Stringer (2012),[2] (archaic admixture).

- ^ Archaic admixture from various sources is known from Europe and Asia (Neanderthals), Southeast Asia and Melanesia (Denisovans) as well as from Western and Southern Africa. The proportion of admixture varies by region, but in all cases has been reported below 10%: In Eurasian mostly estimated at 1–4% (with a high estimate of 3.4–7.3% by Lohse (2014)[3]) in Melanesians estimated at 4–6% (Reich et al. (2010)).[4] Admixture of an unknown archaic hominin in Sub-Saharan African hunter-gatherer populations was estimated at 2% (Hammer et al. (2011)).[5]

- Java, is considered the latest known specimen of H. erectus. Formerly dated to as late as 50,000 to 40,000 years ago, a 2011 study pushed back the date of the extinction of H. e. soloensis to 143,000 years ago at the latest, more likely before 550,000 years ago.[14]

- ^ "Here we report the ages, determined by thermoluminescence dating, of fire-heated flint artefacts obtained from new excavations at the Middle Stone Age site of Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, which are directly associated with newly discovered remains of H. sapiens. A weighted average age places these Middle Stone Age artefacts and fossils at 315±34 thousand years ago. Support is obtained through the recalculated uranium series with electron spin resonance date of 286±32 thousand years ago for a tooth from the Irhoud 3 hominin mandible."[21]

- ^ Estimated split times given in the source cited (in kya): Human-Neanderthal: 530–690, Deep Human [H. sapiens]: 250–360, NKSP-SKSP: 150–190, Out of Africa (OOA): 70–120.[1]

- ^ "By ~130 ka two distinct groups of anatomically modern humans co-existed in Africa: broadly, the ancestors of many modern-day Khoe and San populations in the south and a second central/eastern African group that includes the ancestors of most extant worldwide populations. Early modern human dispersals correlate with climate changes, particularly the tropical African "megadroughts" of MIS 5 (marine isotope stage 5, 135–75 ka) which paradoxically may have facilitated expansions in central and eastern Africa, ultimately triggering the dispersal out of Africa of people carrying haplogroup L3 ~60 ka. Two south to east migrations are discernible within haplogroup L0. One, between 120 and 75 ka, represents the first unambiguous long-range modern human dispersal detected by mtDNA and might have allowed the dispersal of several markers of modernity. A second one, within the last 20 ka signalled by L0d, may have been responsible for the spread of southern click-consonant languages to eastern Africa, contrary to the view that these eastern examples constitute relicts of an ancient, much wider distribution."[36]

- ^ "We studied the branching history of Pygmy hunter–gatherers and agricultural populations from Africa and estimated separation times and gene flow between these populations. The model identified included the early divergence of the ancestors of Pygmy hunter–gatherers and farming populations ~60,000 years ago, followed by a split of the Pygmies' ancestors into the Western and Eastern Pygmy groups – 20,000 years ago."[41]

- ^ Early modern human presence outside of Africa has been proposed to date back to as early as 177,000 years ago.[34]

- ^ The authors of Liu (2010) seem to accept that the individual has African recent ascentry, but with Asian archaic human admixture.[50] See also Dennell (2010).[51] Brief comments at [52] and [53]

- ^ "We found that North African populations have a significant excess of derived alleles shared with Neandertals, when compared to sub-Saharan Africans. This excess is similar to that found in non-African humans, a fact that can be interpreted as a sign of Neandertal admixture. Furthermore, the Neandertal's genetic signal is higher in populations with a local, pre-Neolithic North African ancestry. Therefore, the detected ancient admixture is not due to recent Near Eastern or European migrations. Sub-Saharan populations are the only ones not affected by the admixture event with Neandertals."[107]

- ^ "Of 1,420 sub-Saharan chromosomes, only one copy of B006 was observed in Ethiopia, and five in Burkina Faso, one among the Rimaibe and four among the Fulani and Tuareg, nomad-pastoralists known for having contacts with northern populations (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). B006 only occurrence at the northern and northeastern outskirts of sub-Saharan Africa is thus likely to be a result of gene flow from a non-African source."[108]

- ^ Traits affected by the mutation are sweat glands, teeth, hair shaft thickness and breast tissue.[113][114]

- EDAR, ADH1B, ABCC1, and ALDH2 in particular. The East Asian types of ADH1B are associated with rice domestication and would thus have arisen after the c. 11,000 years ago.[115]

References

- ^ PMID 28971970.

- S2CID 4420496.

- PMID 24532731.

- PMID 21179161.

- ^ PMID 21896735.

- S2CID 49670311.

- ISBN 978-9048190355.

- .

- ^ .

- ^ R. Zhu et al. (2004), New evidence on the earliest human presence at high northern latitudes in northeast Asia.

- doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00110-1. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 July 2011.

- .

- PMID 21738710.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (12 May 2011). "An Arctic refuge for Neanderthals?". nature.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- PMID 28957509.

- S2CID 87081207.

- PMID 22840920.

- PMID 28483040.

- ^ PMID 27127403.

- S2CID 205255853.

- PMID 17372199.

- PMID 27298468.

- ^ Sample, Ian (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens bones ever found shake foundations of the human story". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- S2CID 256771372.

- PMID 30007846.

- S2CID 1454595.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (10 September 2019). "Scientists Find the Skull of Humanity's Ancestor, on a Computer – By comparing fossils and CT scans, researchers say they have reconstructed the skull of the last common forebear of modern humans". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- PMID 31506422.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (10 July 2019). "A Skull Bone Discovered in Greece May Alter the Story of Human Prehistory". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Staff (10 July 2019). "'Oldest remains' outside Africa reset human migration clock". Phys.org. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- PMID 31337897.

- S2CID 195873640.

- ^ PMID 29371468.

- ^ ISBN 978-0190277734.

- PMID 24236171.

- PMID 22570615.

- PMID 19924308.

- PMID 19407144. (Supplementary Data)

- .

- PMID 19360089.

- ^ "Scientists discover oldest known modern human fossil outside of Africa: Analysis of fossil suggests Homo sapiens left Africa at least 50,000 years earlier than previously thought". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (2018). "Modern humans left Africa much earlier". BBC News. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- S2CID 205255425.

- ^ "Human footprints dating back 120,000 years found in Saudi Arabia". phys.org. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- PMID 32948582.

- PMID 21273459.

- ^ "Trail of 'Stone Breadcrumbs' Reveals the Identity of One of the First Human Groups to Leave Africa". ScienceDaily. 1 December 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ Bower, Bruce (27 January 2011). "Hints of earlier human exit from Africa". Science News. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- PMID 20974952.

- S2CID 205060486.

- ^ Modern Humans Emerged Far Earlier Than Previously Thought, Fossils from China Suggest, ScienceDaily (25 October 2010) https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/10/101025172924.htm

- ^ Oldest Modern Human Outside of Africa Found

- PMID 12473485.

- ^ "Lunadong fossils support theory of earlier dispersal of modern man". University of Hawaii at Mānoa. 18 September 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- S2CID 181399291. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- PMID 20203021.

- ^ S2CID 140098861.

- PMID 25770088.

- ^ PMID 31196864.

- PMID 12690579.

- ^ Stix, Gary (2008). "The Migration History of Humans: DNA Study Traces Human Origins Across the Continents". Scientific American. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- S2CID 20296624. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- PMID 30837540.

- .

- PMID 24352235.

- ^ S2CID 4365526.

- S2CID 148777016.

- PMID 30082377.

- PMID 21944045

- LiveScience.

- S2CID 206551893.

- ^ Salleh, Anna (18 October 2013). "Humans dated ancient Denisovan relatives beyond the Wallace Line". ABC Science.

- ^ First Mariners – Archaeology Magazine Archive. Archive.archaeology.org. Retrieved on 2013-11-16.

- ^ "Pleistocene Sea Level Maps". Fieldmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- PMID 21940856.

- PMID 17496137.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (8 May 2007). "From DNA Analysis, Clues to a Single Australian Migration". The New York Times. Australia. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- S2CID 19824757.

- S2CID 205257212.

- ^ Flannery, Tim (2002), "The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People" (Grove Press)

- S2CID 24631308.

- ^ "Fossil Teeth Put Humans in Europe Earlier Than Thought". The New York Times. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ PMID 23055938.

- ISBN 978-0465002214. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- S2CID 33122717.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Stephen "Out of Eden: Peopling of the World" (Robinson; New Ed edition (1 March 2012))

- ^ S2CID 1986562.

- ^ "Atlas of human journey: 45–40,000". The genographic project. National Geographic Society. 1996–2010. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- S2CID 205226924.

- S2CID 4374023.

- ^ "Mamontovaya Kurya:an enigmatic, nearly 40000 years old Paleolithic site in the Russian Arctic" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ a b Hoffecker, J. (2006). A Prehistory of the North: Human Settlements of the Higher Latitudes. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 101.

- ^ Hoffecker, John F. (2002). Desolate landscapes: Ice-Age settlement in Eastern Europe. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. pp. 158–162, 217–233.

- ^ Kathryn E. Fitzsimmons et al., The Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption: New Data on Volcanic Ash Dispersal and Its Potential Impact on Human Evolution, 2013 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065839

- ^ Giaccio, B. et al., High-precision 14C and 40Ar/39Ar dating of the Campanian Ignimbrite (Y-5) reconciles the time-scales of climatic-cultural processes at 40 ka. Sci Rep 7, 45940 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45940

- ^ Hajdinjak, M. et al., Initial Upper Palaeolithic humans in Europe had recent Neanderthal ancestry. Nature 592, 253–257 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03335-3

- ^ Bennett, E.A. et al., Genome sequences of 36,000- to 37,000-year-old modern humans at Buran-Kaya III in Crimea. Nat Ecol Evol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02211-9

- PMID 12743370.

- PMID 15562317.

- PMID 11553319.

- PMID 15562317.

- ^ Hajdinjak et al. Initial Upper Palaeolithic humans in Europe had recent Neanderthal ancestry. Nature 592, 253–257 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03335-3

- PMID 22936568.

- PMID 23410836.

- PMID 23082212.

- PMID 21266489.

- PMID 24159019.

- PMID 29033327.

- PMID 24336922..

- PMID 26500257.

- PMID 23415220.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (14 February 2013). "East Asian Physical Traits Linked to 35,000-Year-Old Mutation". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- PMID 20089146.

- ISSN 2770-5005.

...In contrast, mainland East and Southeast Asians and other Pacific islanders (e.g., Austronesian speakers) are closely related to each other [9,15,16] and here denoted as belonging to an East and Southeast Asian (ESEA) lineage (Box 2). …the ESEA lineage differentiated into at least three distinct ancestries: Tianyuan ancestry which can be found 40,000–33,000 years ago in northern East Asia, ancestry found today across present-day populations of East Asia, Southeast Asia, and Siberia, but whose origins are unknown, and Hòabìnhian ancestry found 8,000-4,000 years ago in Southeast Asia, but whose origins in the Upper Paleolithic are unknown.

- S2CID 206507352.

- ^ ISBN 978-0812971460.

- ^ a b Fitzhugh, Drs. William; Goddard, Ives; Ousley, Steve; Owsley, Doug; Stanford, Dennis. "Paleoamerican". Smithsonian Institution Anthropology Outreach Office. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ "A DNA Search for the First Americans Links Amazon Groups to Indigenous Australians". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- PMID 9050871.

- ^ a b "Atlas of the Human Journey-The Genographic Project". National Geographic Society. 1996–2008. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- OCLC 1031966951.

- OCLC 1238190784.

- OCLC 1102541304.

- ISBN 978-1315509877.

- ^ "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- S2CID 162243347.

- ^ "68 Responses to "Sea will rise 'to levels of last Ice Age'"". Center for Climate Systems Research, Columbia University. 26 January 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ Geggel, Laura (2 April 2021). "1st Americans had Indigenous Australian genes". livescience.com. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- PMID 23840409.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (4 September 2014). "Three-part ancestry for Europeans". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ Curry, Andrew (August 2019). "The first Europeans weren't who you might think". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021.

- PMID 29315301.

- ^ S2CID 219974966.

- ^ John Desmond Clark, From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa, University of California Press, 1984, p. 31

- ^ Igor Kopytoff, The African Frontier: The Reproduction of Traditional African Societies (1989), 9–10 (cited after Igbo Language Roots and (Pre)-History Archived 2019-07-17 at the Wayback Machine, A Mighty Tree, 2011).

- S2CID 162117464.

- PMID 27324836.

- PMID 29741686.

- ^ a b c Meacham, William (1984–1985). "On the improbability of Austronesian origins in South China" (PDF). Asian Perspective. 26: 89–106. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ JSTOR 24936983.

- ISBN 978-1760460952.

- S2CID 128641903.

- ^ Lansing, Steve. "Did a butterfly effect change the history of the Pacific?". Stockholm Resilience Centre. Stockholm University. Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Lawler, Andrew (23 December 2020). "Invaders nearly wiped out Caribbean's first people long before Spanish came, DNA reveals". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020.

- ^ Fagan, B.M. (2007). People of the earth: An introduction to world prehistory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall

- ISBN 978-0813534695.

- ^ Gibbon, pp. 28–31

- ^ Rigby, Bruce. "101. Qaummaarviit Historic Park, Nunavut Handbook" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2006. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Wood, Shannon Raye (April 1992). "Tooth Wear and the Sexual Division of Labour in an Inuit Population" (PDF). Department of Archaeology University of Saskatchewan. Simon Fraser University. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

Further reading

- Demeter F, Shackelford LL, Bacon AM, Duringer P, Westaway K, Sayavongkhamdy T, Braga J, Sichanthongtip P, Khamdalavong P, Ponche JL, et al. (2012). "Anatomically modern human in Southeast Asia (Laos)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (36): 14375–14380. PMID 22908291.

- Litt, Thomas; Richter, Jürgen; Schäbitz, Frank (2021). The Journey of Modern Humans from Africa to Europe. Stuttgart, Germany: Schweizerbart Science Publishers. ISBN 978-3510655342. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ISBN 978-1101870327.; Diamond, Jared (20 April 2018). "A Brand-New Version of Our Origin Story". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- Veeramah, Krishna R.; Hammer, Michael F. (4 February 2014). "The impact of whole-genome sequencing on the reconstruction of human population history". Nature Reviews Genetics. 15 (3): 149–162. S2CID 19375407.