Edwin Henderson

Edwin Henderson | |

|---|---|

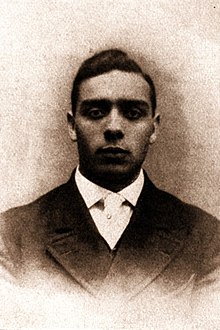

Henderson in 1912 | |

| Born | Edwin Bancroft Henderson November 24, 1883 Washington, D.C., US |

| Died | February 3, 1977 (aged 93) |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse | Mary Ellen Henderson |

Edwin Bancroft Henderson (November 24, 1883 – February 3, 1977), was an American educator and

Early and family life

Henderson was born in southwest Washington, D.C., on November 24, 1883. His father, William Henderson, was a day laborer and his mother Louisa taught him to read at an early age.

He earned a bachelor's degree from Howard University, a master's degree from Columbia University, and a PhD in athletic training from Central Chiropractic College in Kansas City, Missouri.[1] Henderson became the first black man to receive a National Honor Fellowship in the American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation. Shortly before his retirement from the D.C. Schools at age 70, Henderson also received an Alumni Achievement Award from his alma mater, Howard University.[2]

He married Mary Ellen (Nellie) Meriwether Henderson (1886–1976), also a teacher and civil rights advocate, as well as active with the Girl Scouts and League of Women Voters. They moved to Falls Church, Virginia in 1910 shortly after their marriage, and both helped at the Henderson family store. They lived at 307 South Maple Street (originally 307 W. Fairfax Street) for decades; Edwin Henderson also took the colored streetcar line across the Potomac River to his job with the D.C. Public Schools. They also had a summer home at Highland Beach on Chesapeake Bay near Annapolis, Maryland. The Hendersons remained married for 63 years until her death (almost a year before his demise), and were survived by both their sons: Dr. James H. M. Henderson (who became director of Tuskegee's Carver Research Foundation), Dr. Edwin M. Henderson (who became a dentist in the District of Columbia).[5]

Career

Upon graduating as a teacher in 1904, Henderson taught (and later directed) physical education in the D.C. public schools for five decades. During his first three summer breaks, he attended summer sessions at Harvard University to study medicine or health and physical education. There, Henderson also learned the then-new game of basketball, which he introduced to other young black men at the 12th Street (Colored) YMCA upon returning to Washington, D.C.[6] Soon, they were playing teams from Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York. His D.C. teams (Howard University adopted the 12th street team as its first varsity basketball team) won the national basketball championships in 1909 and 1910.[2][7]

From those early years through the 1950s, Henderson also played and coached basketball, as well as refereed football and baseball contests and occasionally sparred in the boxing ring. He helped organize the first all-black amateur athletic association, the Interscholastic Athletic Association (1906), the Washington, D.C., Public School Athletic League (1906) and the Eastern Board of Officials (1905) (a training center that, for decades was the go-to pool for highly qualified African American referees). Henderson taught and influenced perhaps hundreds of thousands of Washington area schoolchildren in basketball, including Duke Ellington and Charles Drew.

From 1926 until 1954, Henderson directed physical education for African American children in the segregated Washington, D.C., school system. He used sports to combat truancy, as well as instill character, forming teams in each fifth and sixth grade classroom. In 1943 his contributions were recognized by his being named to the National Council on Physical Fitness and the subcommittee on colleges and schools of the National Committee on Physical Fitness. Henderson retired shortly after the Brown v. Board of Education decision made segregated schooling obsolete, so the position evaporated, but he was made a fellow of the American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation.

During World War II, Henderson helped train Army recruits. In the 1940s, Henderson also advocated for civil rights, including for interracial athletic competitions. Among the battles he fought in the 1940s was picketing the Uline Arena (originally a hockey venue and later called the "Washington Coliseum"), because the Uline would not allow African Americans and Whites to compete against each other. After hearing the AAU Golden Gloves Boxing competitions were to be held at the Uline, Henderson encouraged picketing until Eugene Meyer, publisher of The Washington Post, withdraw his support for holding the event there. Efforts by Henderson and Meyer ultimately led to the AAU allowing integrated boxing in the District of Columbia.[8]

Henderson wrote several seminal books about African American participation in sports, including his landmark work, The Negro In Sports (Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, Inc., 1939). In 1910–1913, Henderson co-authored an annual handbook published by the

Beyond athletics, Henderson and his wife, Nellie Henderson, also an educator, fought against segregation discrimination in housing and education. Five years after they moved to Virginia, in 1915, the Falls Church town council passed an ordinance to create segregated districts within the town. Dr. Henderson, Joseph Tinner and seven other community members, formed the Colored Citizens Protective League, and started a letter writing campaign to address the council and this ordinance. Dr. Henderson and his wife, Mary Ellen, were members of the NAACP, in Washington, D.C., so, they also wrote a letter to W. E. B. Du Bois asking permission to start a NAACP chapter in Falls Church, Virginia. The NAACP headquarters advised that the organization had no rural branches. However, they were given permission to operate as a standing committee under the authority of the NAACP; thus formed the Fairfax County branch in 1918.[9] Ironically, although the Hendersons won that initial town council ordinance spat, the council then ceded the Seven Corners area back to Fairfax County (because, Henderson said, "in those days Negroes were Republican"), but decades later unsuccessfully tried to annex it back, after it had become Fairfax County's largest single source of revenue.[10]

Dr. Henderson also twice served as President of the NAACP's Virginia Council, from 1955 to 1958, the height of

E. B. Henderson also wrote many letters to the editor, especially after his retirement, to local newspapers in Washington, D.C., and Virginia. He claimed to have had more than 3,000 letters published in over a dozen newspapers.[8] The majority of the letters concerned race relations and sought equality for African Americans in the United States as well as the local Washington, D.C., metropolitan area. Today, the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation and The Washington Post co-sponsor a "Dear Editor" contest to secondary school aged students in Northern Virginia in his honor.

Death and legacy

Henderson died of cancer in 1977, at age 93, at his son's home in Tuskegee, Alabama. He survived his beloved wife of 63 years by one year. They were both cremated and their ashes interred in Woodlawn Cemetery. They were survived by their sons, five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, as well as by his sister, Mrs. Annie H. Briggs of Falls Church, Virginia.[5] His papers are held at Howard University's Moorland-Spingarn Research Center.[11]

During his lifetime, Henderson received some recognition, apart from an elaborate sendoff from his Second Baptist Church of Falls Church when he left for Alabama in 1965.[12] The Fairfax County Council on Human Relations, where he had served as program chairman, gave him a testimonial in 1960.[2] His Falls Church/Fairfax County NAACP branch also celebrated its 50th anniversary shortly before his departure.[13] In 1972, Black Sports magazine cited Henderson as "one of the foremost black Americans of all time."[2] In 1973, Henderson was elected Honorary President of the North American Society for Sport History.[2] In 1974, along with Joe Louis, Jackie Robinson, Jesse Owens, Bill Russell and Althea Gibson, he became an inaugural member of the Black Athletes Hall of Fame.

The honors continued posthumously. In 1982, Fairfax County dedicated its Providence Recreation Center in Edwin Henderson's honor. In 1985, the

In 1999, the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation erected a pink granite (trondhjemite) archway memorializing the founders of the Colored Citizens Protective League (CCPL) which eventually became the NAACP's first rural branch.

Since 1993, the Annual Tinner Blues Festival has taken place on the second Saturday of June in Falls Church's Cherry Hill Park. Many national and area blues musicians play at the event, which also recognizes the late Piedmont Blues guitarist/singer John Jackson, who made his home in Northern Virginia.

In 2013, Henderson was inducted posthumously into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.[16]

In 2018, the Library of Virginia honored Henderson as one of its Strong Men and Women.[17]

In 2022 the University of the District of Columbia renamed building 47 on their campus after Henderson.[18]

References

- ^ a b c "Edwin Bancroft Henderson (1883–1977) •". 5 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Hailey, Jean R. (February 5, 1977). "Edwin Henderson, Educator, 93, Dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Northern Virginia Sun, "Local Black Leader Dies," February 3, 1977

- ^ see note on talk page

- ^ a b c Northern Virginia Sun obituary

- ^ Mary Ellen Perry, "Never Too Old to Dream: NAACP Pioneer Recalls, at 92, the Milestones" Washington Star March 26, 1976 p. E-1, E-5

- ^ "Edwin B. Henderson | the Black Fives Foundation". 16 April 2009.

- ^ a b Ungrady, Dave (6 September 2013). "E.B. Henderson brought basketball to the District". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Historical Marker C-91 at http://dhr.virginia.gov/HistoricMarkers/ Archived 2016-10-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ H.C. Burchard Jr. "Old Warrior Against Segregation Leaving Field at 82", Washington Star (undated in Arlingtonlibrary clippings file, possibly November 1965)

- ^ Washington Star 1976

- ^ Mary Ellen Perry, "Never Too Old to Dream", Washington Star (March 26, 1976 p. E-1

- ^ H.C. Burchard Jr, "old Warrior Against Segregation Leaving Field at 82" Washington Star (undated clipping, probably November 1965)

- ^ dedicatory leaflet in Arlington library clippings file

- ^ "Edwin Bancroft and Mary Ellen Henderson House National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). www.dhr.virginia.gov. Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ "Five Direct-Elect Members Announced for the Class of 2013 By the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame" (Press release). Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. February 15, 2013. Archived from the original on February 18, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Strong Men & Women in Virginia History – Library of Virginia Education".

- ^ "UDC renames sports complex after Dr. Edwin Bancroft Henderson, the 'grandfather of Black basketball'".

Further reading

- James H.N. Henderson and Betty F. Henderson, Molder of Men: Portrait of a "Grand Old Man" Edwin Bancroft Henderson