Effects of hormones on sexual motivation

Sexual motivation is influenced by hormones such as testosterone, estrogen, progesterone, oxytocin, and vasopressin. In most mammalian species, sex hormones control the ability and motivation to engage in sexual behaviours.

Measuring sexual motivation

Sexual motivation can be measured using a variety of different techniques. Self-report measures, such as the Sexual Desire Inventory, are commonly used to detect levels of sexual motivation in humans. Self-report techniques such as the bogus pipeline can be used to ensure individuals do not falsify their answers to represent socially desirable results. Sexual motivation can also be implicitly examined through frequency of sexual behaviour, including masturbation.

Hormones

Testosterone

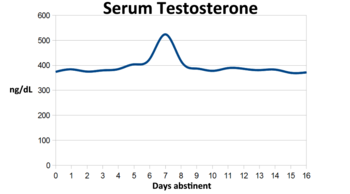

Testosterone levels in males have been shown to vary according to the ovulating state of females. Males who were exposed to scents of ovulating women recorded higher testosterone levels than males who were exposed to scents of nonovulating women.[3] Being exposed to female ovulating cues may increase testosterone, which in turn may increase males' motivation to engage in, and initiate, sexual behaviour. Ultimately, these higher levels of testosterone may increase the reproductive success of males exposed to female ovulation cues.

The relationship between testosterone and female sexual motivation is somewhat ambiguous. Research suggests

It is also suggested that levels of testosterone are related to the type of relationship in which one is involved. Men involved in

Estrogens and progesterone

Females at different stages of their menstrual cycle have been shown to display differences in

Following natural or surgically induced menopause, many women experience declines in sexual motivation.[11] Menopause is associated with a rapid decline of estrogen, as well as a steady rate of decline of androgens.[12] The decline of estrogen and androgen levels is believed to account for the lowered levels of sexual desire and motivation in postmenopausal women, although the direct relationship is not well understood.

Oxytocin and vasopressin

The hormones oxytocin and vasopressin are implicated in regulating both male and female sexual motivation. Oxytocin is released at orgasm and is associated with both sexual pleasure and the formation of emotional bonds.[13] Based on the pleasure model of sexual motivation, the increased sexual pleasure that occurs following oxytocin release may encourage motivation to engage in future sexual activities. Emotional closeness can be an especially strong predictor of sexual motivation in females and insufficient oxytocin release may subsequently diminish sexual arousal and motivation in females.

High levels of vasopressin can lead to decreases in sexual motivation for females.

Nonprimate species

The hormonal influences of sexual motivation are much more clearly understood for nonprimate females. Suppression of estrogen receptors in the

An increase in vasopressin has been observed in female rats which have just given birth. Vasopressin is associated with aggressive and hostile behaviours, and is postulated to decrease sexual motivation in females. Vasopressin administered in the female rat brain has been observed to result in an immediate decrease in sexual motivation.[13]

Sexual orientation

Little research has been conducted on the effect of hormones on sexual motivation for same-sex sexual contact. One study observed the relationship between sexual motivation in

Both lesbian and bisexual women showed decreases in sexual motivation for other-sex sexual contact at peak estrogen levels, with greater changes in the bisexual group than the lesbian group.[citation needed]

Clinical research

Men

- Testosterone is critical for sexual desire, function, and arousal in men.

- Men experience medical castration causes profound sexual dysfunction in men.[29][30] Combined marked suppression of testicular testosterone production resulting in testosterone levels of just above the castrate/female range (70 to 80% decrease, to 100 ng/dL on average) and marked androgen receptor antagonism with high-dosage cyproterone acetate monotherapy causes profound sexual dysfunction in men.[29][31] Treatment of men with medical castration and add-back of multiple dosages of testosterone to restore testosterone levels (to a range of about 200 to 900 ng/dL) showed that testosterone dose-dependently restored sexual desire and erectile function in men.[32] High-dosage monotherapy with an androgen receptor antagonist such as bicalutamide or enzalutamide, which preserves testosterone and estradiol levels, has a minimal to moderate negative effect on sexual desire and erectile function in men in spite of strong blockade of the androgen receptor.[29][33][34][35]

- Estradiol supplementation maintains greater sexual desire in men with surgical or medical castration.estrogen deficiency, appear to have normal sexual desire, function, and activity.[22][21] However, estradiol supplementation in some men with aromatase deficiency increased sexual desire and activity but not in other men with aromatase deficiency.[22][21][40] Treatment with the antiestrogenic selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) tamoxifen has been found to decrease sexual desire in men treated with it for male breast cancer.[41] However, other studies have not found or reported decreased sexual function in men treated with SERMs including tamoxifen, clomifene, raloxifene, and toremifene.[22][42]

- 5α-Reductase inhibitors, which block the conversion of testosterone into DHT, result in a slightly increased risk of sexual dysfunction with an incidence of decreased libido and erectile dysfunction of about 3 to 16%.[43][44][24] Treatment of healthy men with multiple dosages of testosterone enanthate, with or without the 5α-reductase inhibitor dutasteride, showed that dutasteride did not significantly influence changes in sexual desire and function.[45][24] Treatment of men with high-dosage bicalutamide therapy, with or without the 5α-reductase inhibitor dutasteride, showed that dutasteride did not significantly influence sexual function.[46] Combined high-dosage bicalutamide therapy plus dutasteride showed less sexual dysfunction than medical castration similarly to high-dosage bicalutamide monotherapy.[47]

- Treatment of men with very high-dosage DHT (a non-aromatizable androgen), which resulted in an increase in DHT levels by approximately 10-fold and complete suppression of testosterone and estradiol levels, showed that none of the measures of sexual function were significantly changed with the exception of a mild but significant decrease in sexual desire.[42][48][24] Treatment of hypogonadal men with the aromatizable testosterone undecanoate and the non-aromatizable mesterolone showed that testosterone undecanoate produced better improvements in mood, libido, erection, and ejaculation than did mesterolone.[21][42] However, the dosage of mesterolone could have been suboptimal.[42]

Women

- Estradiol seems to be the most important hormone for sexual desire in women.Periovulatory levels of estradiol increase sexual desire in postmenopausal women.[49] Based on animal research, progesterone may also be involved in sexual function in women.[52][53][54] Very limited clinical research suggests that progesterone does not increase sexual desire and may decrease it.[55]

- There is little support for the notion that physiological levels of testosterone are important for sexual desire in women, although supraphysiological levels of testosterone can increase sexual desire in women similarly to the high levels in men.[49][28] There is little to no correlation between total testosterone levels within the normal physiological range and sexual desire in premenopausal women.[28]

- Sexual desire is not increased in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in spite of high testosterone levels.[28] Women with PCOS actually experience an improvement in sexual desire following treatment of their condition, likely due improved psychological functioning (e.g., body image).[28] Sexual desire is not decreased in women with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) relative to unaffected women in spite of a completely non-functional androgen receptor.[28]

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of research on variation during the menstrual cycle of women's sexual activity with partners and the effects of the use of the combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) by women on their sexual desire show that sexual desire is self-reported to be unchanged in most women taking COCPs, but also conclude that the effects of COCPs on women's sexual desire is not well-studied and that women experience increased sexual activity with partners in the last third of the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle and at ovulation (when levels of endogenous estradiol and luteinizing hormones are heightened) as compared with the luteal phase and during menstruation.[28][56][57][51] Almost all combined birth control pills contain the potently liver-active estrogen ethinylestradiol, and the typical doses of ethinylestradiol present in combined birth control pills increase sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) levels by 2- to 4-fold and consequently decrease free testosterone levels by 40 to 80%.[58] Cross-sectional research has shown that SHBG is inversely correlated with sexual desire in premenopausal women.[59]

- There are conflicting reports on the effects of combined birth control pills on sexual function in women.

- Low dosages of testosterone that result in physiological levels of testosterone (< 50 ng/dL) do not increase sexual desire in women.voice changes) with long-term therapy in women.[49][28] High dosages of testosterone but not low dosages of testosterone enhance the effects of low dosages of estrogens on sexual desire.[49][28] Tibolone, a combined estrogen, progestin, and androgen, may increase sex drive to a greater extent than standard estrogen–progestogen therapy in postmenopausal women.[65][66][67][68]

Transgender individuals

- Testosterone therapy increases sexual desire and arousal in transgender women after a temporary decrease.[71]

See also

References

- S2CID 2214664.

- ^ S2CID 2214664.

- S2CID 18170407.

- PMID 977822.

- S2CID 21548908.

- ^ S2CID 10492318.

- S2CID 10545604.

- ^ S2CID 37260925.

- PMID 9633114.

- S2CID 53074076.

- .

- PMID 20444881.

- ^ a b c d Hiller, J. (2005). Gender differences in sexual motivation. The journal of men's health & gender, 2(3), 339-345.

- S2CID 2106719.

- S2CID 36207185.

- PMID 19887773.

- PMID 22120688.

- S2CID 13989776.

- PMID 27436075.

- S2CID 14012244.

- ^ PMID 21074215.

- ^ PMID 22512993.

- ^ PMID 23484454.

- ^ PMID 28472278.

- PMID 7803627.

- PMID 18093638.

- PMID 22231829.

- ^ PMID 27785108.

- ^ S2CID 28215804.

- PMID 29289377.

- PMID 1838080.

- ^ PMID 24024838.

- S2CID 8639102.

- S2CID 46966712.

- PMID 24739897.

- S2CID 14949511.

- S2CID 262018256.

A favourable feature of flutamide therapy has been its lesser effect on libido and sexual potency; fewer than 20% of patients treated with flutamide alone reported such changes. In contrast, nearly all patients treated with oestrogens or estramustine phosphate reported loss of sexual potency. [...] In comparative therapeutic trials, loss of potency has occurred in all patients treated with stilboestrol or estramustine phosphate compared with 0 to 20% of those given flutamide alone (Johansson et al. 1987; Lund & Rasmussen 1988).

- PMID 19243704.

- ISBN 978-0-443-02613-3.

Treatment of sexual offenders. Hormone therapy. [...] Oestrogens may cause breast hypertrophy, testicular atrophy, osteoporosis (oral ethinyl oestradiol 0.01-0.05 mg/day causes least nausea). Depot preparation: oestradiol [undecyleate] 50-100mg once every 3–4 weeks. Benperidol or butyrophenone and the antiandrogen cyproterone acetate also used.

- )

- S2CID 45482984.

- ^ S2CID 29435946.

- PMID 27672412.

- S2CID 11624116.

- PMID 22396515.

- PMID 27330919.

- PMID 26702991.

Dutasteride and Bicalutamide is a regimen of non-inferior efficacy to LHRH agonist based regimens for prostate volume reduction prior to permanent implant prostate brachytherapy. D + B has less sexual toxicity compared to LHRH agonists prior to implant and for the first 6 months after implant. D + B is therefore an option to be considered for prostate volume reduction prior to PIPB.

- PMID 24751323.

- ^ PMID 26589379.

- S2CID 7140458.

- ^ PMID 31513819.

- PMID 17431228.

- PMID 18374402.

- PMID 26944462.

- ^ PMID 26944460.

- S2CID 34748865.

- PMID 22788250.

- ISBN 978-92-832-1291-1.

- S2CID 225473332.

- PMID 27622561.

- PMID 20827250.

- PMID 29211888.

- S2CID 20250916.

Among the slight and temporary adverse events [of flutamide], most frequently reported and not requesting treatment discontinuation were headache (7.8%), respiratory tract disorders (7.0%), nausea and/or vomiting (4.0%), diarrhea (4.0%), dry skin (9.5%), and reduction of libido (4.5%).

- S2CID 46782286.

[...] changes in serum levels of the aminotransferases [11] or side effects (stomach pain, headache, dry skin, nausea, increased appetite, decrease of libido) are only occasionally seen [with flutamide] [10, 11].

- PMID 7752950.

- PMID 9881330.

- S2CID 11724490.

- PMID 18488873.

- PMID 28945902.

- PMID 27084565.

- S2CID 211014269.