Effects of long-term benzodiazepine use

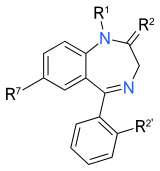

| Benzodiazepines |

|---|

|

The effects of long-term benzodiazepine use include

Some of the symptoms that could possibly occur as a result of a withdrawal from benzodiazepines after long-term use include emotional clouding,

While benzodiazepines are highly effective in the short term, adverse effects associated with long-term use, including impaired cognitive abilities, memory problems, mood swings, and overdoses when combined with other drugs, may make the risk-benefit ratio unfavourable. In addition, benzodiazepines have reinforcing properties in some individuals and thus are considered to be addictive drugs, especially in individuals that have a "drug-seeking" behavior; further, a physical dependence can develop after a few weeks or months of use.[13] Many of these adverse effects associated with long-term use of benzodiazepines begin to show improvements three to six months after withdrawal.[14][15]

Other concerns about the effects associated with long-term benzodiazepine use, in some, include dose escalation, benzodiazepine use disorder, tolerance and benzodiazepine dependence and benzodiazepine withdrawal problems. Both physiological tolerance and dependence can be associated with worsening the adverse effects associated with benzodiazepines. Increased risk of death has been associated with long-term use of benzodiazepines in several studies; however, other studies have not found increased mortality. Due to conflicting findings in studies regarding benzodiazepines and increased risks of death including from cancer, further research in long-term use of benzodiazepines and mortality risk has been recommended; most of the available research has been conducted in prescribed users, even less is known about illicit misusers.[16][17] The long-term use of benzodiazepines is controversial and has generated significant debate within the medical profession. Views on the nature and severity of problems with long-term use of benzodiazepines differ from expert to expert and even from country to country; some experts even question whether there is any problem with the long-term use of benzodiazepines.[18]

Symptoms

Effects of long-term benzodiazepine use may include

Cognitive status

Long-term benzodiazepine use can lead to a generalised impairment of

Effect on sleep

Sleep can be adversely affected by benzodiazepine dependence. Possible adverse effects on sleep include induction or worsening of sleep disordered breathing. Like alcohol,

Mental and physical health

The long-term use of benzodiazepines may have a similar effect on the brain as alcohol, and is also implicated in depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), mania, psychosis, sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, delirium, and neurocognitive disorders.[35][36] However a 2016 study found no association between long-term usage and dementia.[37] As with alcohol, the effects of benzodiazepine on neurochemistry, such as decreased levels of serotonin and norepinephrine, are believed to be responsible for their effects on mood and anxiety.[38][39][40][41][42][43] Additionally, benzodiazepines can indirectly cause or worsen other psychiatric symptoms (e.g., mood, anxiety, psychosis, irritability) by worsening sleep (i.e., benzodiazepine-induced sleep disorder). These effects are paradoxical to the use of benzodiazepines, both clinically and non-medically, in management of mental health conditions.[44][45]

Long-term benzodiazepine use may lead to the creation or exacerbation of physical and mental health conditions, which improve after six or more months of abstinence. After a period of about 3 to 6 months of abstinence after completion of a gradual-reduction regimen, marked improvements in mental and physical wellbeing become apparent. For example, one study of hypnotic users gradually withdrawn from their hypnotic medication reported after six months of abstinence that they had less severe sleep and anxiety problems, were less distressed, and had a general feeling of improved health. Those who remained on hypnotic medication had no improvements in their insomnia, anxiety, or general health ratings.[15] A study found that individuals having withdrawn from benzodiazepines showed a marked reduction in use of medical and mental health services.[46][non-primary source needed]

Approximately half of patients attending mental health services for conditions including

Daily users of benzodiazepines are also at a higher risk of experiencing

A study of 50 patients who attended a benzodiazepine withdrawal clinic found that, after several years of chronic benzodiazepine use, a large portion of patients developed health problems including

Long-term use of benzodiazepines can induce

In addition, chronic use of benzodiazepines is a risk factor for

Immune system

Chronic use of benzodiazepines seemed to cause significant immunological disorders in a study of selected outpatients attending a psychopharmacology department.

Suicide and self-harm

Use of prescribed benzodiazepines is associated with an increased rate of suicide or attempted

Carcinogenicity

There has been some controversy around the possible link between benzodiazepine use and development of cancer; early cohort studies in the 1980s suggested a possible link, but follow-up case-control studies have found no link between benzodiazepines and cancer. In the second U.S. national cancer study in 1982, the

Brain damage evidence

In a study in 1980 in a group of 55 consecutively admitted patients having engaged in non-medical use of exclusively sedatives or hypnotics, neuropsychological performance was significantly lower and signs of intellectual impairment significantly more often diagnosed than in a matched control group taken from the general population. These results suggested a relationship between non-medical use of sedatives or hypnotics and cerebral disorder.[68]

A publication asked in 1981 if lorazepam is more toxic than diazepam.[69]

In a study in 1984, 20 patients having taken long-term benzodiazepines were submitted to brain CT scan examinations. Some scans appeared abnormal. The mean ventricular-brain ratio measured by planimetry was increased over mean values in an age- and sex-matched group of control subjects but was less than that in a group of alcoholics. There was no significant relationship between CT scan appearances and the duration of benzodiazepine therapy. The clinical significance of the findings was unclear.[70]

In 1986, it was presumed that permanent brain damage may result from chronic use of benzodiazepines similar to alcohol-related brain damage.[71]

In 1987, 17 inpatient people who used high doses of benzodiazepines non-medically have anecdotally shown enlarged cerebrospinal fluid spaces with associated cerebral atrophy. Cerebral atrophy reportedly appeared to be dose dependent with low-dose users having less atrophy than higher-dose users.[72]

However, a CT study in 1987 found no evidence of cerebral atrophy in prescribed benzodiazepine users.[73]

In 1989, in a 4- to 6-year follow-up study of 30 inpatient people who used benzodiazepines non-medically,

A CT study in 1993 investigated brain damage in benzodiazepine users and found no overall differences to a healthy control group.[75]

A study in 2000 found that long-term benzodiazepine therapy does not result in brain abnormalities.[76]

Withdrawal from high-dose use of

A 2018 review of the research found a likely causative role between the use of benzodiazepines and an increased risk of dementia,[80] but the exact nature of the relationship is still a matter of debate.[81]

History

Benzodiazepines, when introduced in 1961, were widely believed to be safe drugs but as the decades went by increased awareness of

Political controversy

In 1980, the

In 1980, the

Declassified Medical Research Council meeting

The

Controversy resulted in 2010 when the previously secret files came to light over the fact that the Medical Research Council was warned that benzodiazepines prescribed to millions of patients appeared to cause

Professor Lader, who chaired the MRC meeting, declined to speculate as to why the MRC declined to support his request to set up a unit to further research benzodiazepines and why they did not set up a special safety committee to look into these concerns. Professor Lader stated that he regrets not being more proactive on pursuing the issue, stating that he did not want to be labeled as the guy who pushed only issues with benzos. Professor Ashton also submitted proposals for grant-funded research using MRI, EEG, and cognitive testing in a randomized controlled trial to assess whether benzodiazepines cause permanent damage to the brain, but similarly to Professor Lader was turned down by the MRC.[97]

The MRC spokesperson said they accept the conclusions of Professor Lader's research and said that they fund only research that meets required quality standards of scientific research, and stated that they were and continue to remain receptive to applications for research in this area. No explanation was reported for why the documents were sealed by the Public Records Act.[97]

Jim Dobbin, who chaired the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Involuntary Tranquilliser Addiction, stated that:

Many victims have lasting physical, cognitive and psychological problems even after they have withdrawn. We are seeking legal advice because we believe these documents are the bombshell they have been waiting for. The MRC must justify why there was no proper follow-up to Professor Lader's research, no safety committee, no study, nothing to further explore the results. We are talking about a huge scandal here.[97]

The legal director of Action Against Medical Accidents said urgent research must be carried out and said that, if the results of larger studies confirm Professor Lader's research, the government and MRC could be faced with one of the biggest group actions for damages the courts have ever seen, given the large number of people potentially affected. People who report enduring symptoms post-withdrawal such as neurological pain, headaches, cognitive impairment, and memory loss have been left in the dark as to whether these symptoms are drug-induced damage or not due to the MRC's inaction, it was reported. Professor Lader reported that the results of his research did not surprise his research group given that it was already known that alcohol could cause permanent brain changes.[97]

Class-action lawsuit

Benzodiazepines spurred the largest-ever

Special populations

Neonatal effects

Benzodiazepines have been found to cause teratogenic malformations.

Benzodiazepines, like many other sedative hypnotic drugs, cause

Concerns regarding whether benzodiazepines during pregnancy cause major malformations, in particular cleft palate, have been hotly debated in the literature. A

Elderly

Significant toxicity from benzodiazepines can occur in the elderly as a result of long-term use.

A review of the evidence has found that whilst long-term use of benzodiazepines impairs memory, its association with causing dementia is not clear and requires further research.[119] A more recent study found that benzodiazepines are associated with an increased risk of dementia and it is recommended that benzodiazepines be avoided in the elderly.[120] A later study, however, found no increase in dementia associated with long-term usage of benzodiazepine.[37]

See also

- Long-term effects of alcohol consumption

- Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- Benzodiazepine dependence

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-87997-2.

- ^ "Discontinuation of long-term benzodiazepine use: 10-year follow-up". Oxford Academic Journals. 30 December 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ a b Ford C, Law F (July 2014). "Guidance for the use and reduction of misuse of benzodiazepines and other hypnotics and anxiolytics in general practice". smmgp.org.uk. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-07215-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-852748-0.

- ^ PMID 2576073.

- ^ National Drug Strategy; National Drug Law Enforcement Research Fund (2007). "Benzodiazepine and pharmaceutical opioid misuse and their relationship to crime - An examination of illicit prescription drug markets in Melbourne, Hobart and Darwin" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ PMID 3258735.

- ISBN 978-0-8039-7477-7.

- ^ PMID 28257172.

- ^ National Drug Strategy; National Drug Law Enforcement Research Fund (2007). "Benzodiazepine and pharmaceutical opioid misuse and their relationship to crime - An examination of illicit prescription drug markets in Melbourne, Hobart and Darwin" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- |intentional=yes}}.)

- PMID 10211911.

- ^ PMID 18377143.

- PMID 24629629.

- ^ S2CID 20125264.

- PMID 20305598.

- ISBN 978-0-19-852783-1.

- ISBN 978-0-19-852518-9.

- PMID 2889724.

- S2CID 43176363.

- S2CID 45641761.

- ISBN 9781119097655.

- S2CID 15340907.

- S2CID 630714.

- PMID 15762814.

- PMID 15033227.

- S2CID 41395763.

- S2CID 56883960.

- ISBN 9780444510051.

- S2CID 1709063.

- PMID 15003439.

- ISBN 978-0-19-530659-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-852783-1.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- ^ PMID 26837813.

- ISBN 978-0-19-852518-9.

- ^ Professor Heather Ashton (2002). "Benzodiazepines: How They Work and How to Withdraw".

- ^ PMID 3578580.

- PMID 2857068. Archived from the originalon 16 May 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- PMID 10779253.

- ^ Tasman A; Kay J; Lieberman JA, eds. (2008). Psychiatry, third edition. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 2603–2615.

- .

- S2CID 38614605.

- PMID 7712252.

- ^ PMID 7769598.

- PMID 21714826.

- S2CID 40188442.

- PMID 2380692.

- PMID 2857068. Archived from the originalon 16 May 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- PMID 17711589.

- PMID 2886145.

- S2CID 19145509.

- PMID 1675688.

- PMID 14966178.

- PMID 7562864.

- PMID 7908607.

- S2CID 27443374.

- PMID 9408553.

- S2CID 37418398.

- PMID 19223438.

- PMID 6507663.

- PMID 15555813.

- ^ Daniel F. Kripke (2013). "Risks of Chronic Hypnotic Use". Mortality Associated with Prescription Hypnotics. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- ^ Kripke, Daniel F (2008). "Evidence That New Hypnotics Cause Cancer" (PDF). Department of Psychiatry, UCSD.

the likelihood of cancer causation is sufficiently strong now that physicians and patients should be warned that hypnotics possibly place patients at higher risk for cancer.

- PMID 27667780.

- PMID 7352578.

- PMID 6111030.

- S2CID 33183574.

- S2CID 44304601.

- S2CID 7536198.

- S2CID 33179124.

- PMID 2743035.

- S2CID 46278124.

- PMID 10653201.

- S2CID 32008006.

- ^ Ashton CH. "Long-Term Effects of Benzodiazepine Usage: Research Proposals, 1995–96". University of Newcastle – School of Neurosciences: benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ^ Ashton CH (29 August 2002). "NO EVIDENCE THAT BENZODIAZEPINES ARE "LOCKED UP" IN TISSUES FOR YEARS". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- S2CID 49351844.

- PMID 30098211.

- PMID 19524858.

- PMID 6605211.

- PMID 6109269.

- PMID 16860264.

- S2CID 46966796.

- ^ National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse (2007). "Drug misuse and dependence – UK guidelines on clinical management" (PDF). United Kingdom: Department of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-6998-3.

- PMID 19900604.

- ^ a b Lader; Morgan; Shepherd; Williams, Paul; Skegg; Parish; Tyrer, Peter; Inman; Marks, John; Harris, Peter; Hurry, Tom (1980). "Benzodiazepine dependence : papers, notes and correspondence; report of an ad-hoc meeting held on 23rd September 1981 submitted to Neuro Board in January 1982 and subsequent correspondence". England: The National Archives.

- ^ DrugScope; Gemma Reay; Dr Brian Iddon MP. "All-Party Parliamentary Drugs Misuse Group – An Inquiry into Physical Dependence and Addiction to Prescription and Over-the-Counter Medication" (PDF). UK: DrugScope.org.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2009.

2007–2008

- ^ Dawn Primarolo; David Mellor (18 July 1989). "Benzodiazepines". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom.

- ^ Audrey Wise; Alan Milburn (6 May 1998). "Benzodiazepines". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom.

- ^ Yvette Cooper; Phil Woolas (11 November 1999). "Benzodiazepine". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom.

- Mr. John Hutton (7 December 1999). "Benzodiazepines". England: www.parliament.uk. Archived from the originalon 3 March 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

The story of benzodiazepines is of awesome proportions and has been described as a national scandal. The impact is so large that it is too big for Governments, regulatory authorities, and the pharmaceutical industry to address head on, so the scandal has been swept under the carpet. My reasons for bringing the debate to the Chamber are numerous and reflect the many strands that weave through the issue.

- ^ Michael Behan; Jim Dobbin (20 July 2009). "ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUP ON INVOLUNTARY TRANQUILLISER ADDICTION, SUBMISSION TO EQUALITIES AND HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION" (PDF). AddictionToday.org.

The discrimination is large scale, long-standing and deliberate. Government Departments are aware that they are discriminating but reject the available solutions. The discrimination has disastrous effects on the lives of those affected.

- ^ a b c d e Nina Lakhani (7 November 2010). "Drugs linked to brain damage 30 years ago". The Independent on Sunday. United Kingdom.

- PMID 1389432.

- ^ Peart R (1 June 1999). "Memorandum by Dr Reg Peart". Minutes of Evidence. Select Committee on Health, House of Commons, UK Parliament. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- PMID 15785787.

- S2CID 36855278.

- S2CID 170761.

- S2CID 24278061.

- PMID 1983095.

- ^ S2CID 141169096.

- PMID 11448448.

- PMID 11483023.

- PMID 14741749.

- PMID 3887421.

- S2CID 11592187.

- PMID 7881198.

- PMID 9748174.

- S2CID 13121885.

- S2CID 36105472.

- PMID 15011406.

- PMID 8843497.

- PMID 17485699.

- S2CID 5631182.

- S2CID 28244901.

- PMID 19546656.