Egypt–Mesopotamia relations

Egypt–Mesopotamia relations were the relations between the civilizations of

Prior to a specific Mesopotamian influence there had already been a longstanding influence from

Mesopotamian influences can be seen in the visual arts of Egypt, in architecture, in technology, weaponry, in imported products, religious imagery, in agriculture and livestock, in genetic input, and also in the likely transfer of writing from Mesopotamia to Egypt[4] and generated "deep-seated" parallels in the early stages of both cultures.[2]

Influences on Egyptian trade and art (3500–3200 BCE)

(3300–3200 BCE)

There was generally a high-level of trade between

Designs and objects

Distinctly foreign objects and art forms entered Egypt during this period, indicating contacts with several parts of

Mesopotamian-style pottery in Egypt (3500 BCE)

Red-slipped spouted pottery items dating to around 3500 BCE (

Spouted jars of Mesopotamian design start to appear in Egypt in the

Adoption of Mesopotamian-style maceheads

Egyptians used traditional disk-shaped

Cylinder seals

It is generally thought that

In Egypt, cylinder seals suddenly appear without any local antecedents from around Naqada II c-d (3500–3300 BCE).

Cylinder seals were made in Egypt as late as the

Other objects and designs

In addition, Egyptian objects were created which clearly mimic Mesopotamian forms, although not slavishly.

Temples and pyramids

Egyptian architecture also was influenced, as it adopted various elements of earlier Mesopotamian temple and civic architecture.[26]

Recessed niches in particular, which are characteristic of Mesopotamian temple architecture, were adopted for the design of false doors in the tombs of the First Dynasty and Second Dynasty, from the time of the Naqada III period (circa 3000 BCE).[26][27] It is unknown if the transfer of this design was the result of Mesopotamian builders and architects in Egypt, or if temple designs on imported Mesopotamian seals may have been a sufficient source of inspiration for Egyptian architects to manage themselves.[26]

The design of the

Transmission

The route of this trade is difficult to determine, but direct Egyptian contact with

The intensity of the exchanges suggest however that the contacts between Egypt and Mesopotamia were often direct, rather than merely through middlemen or through trade.[2] Uruk had known colonial outposts of as far as Habuba Kabira, in modern Syria, insuring their presence in the Levant.[31] Numerous Uruk cylinder seals have also been uncovered there.[31] There have been suggestions that Uruk may have had a colonial outpost and a form of colonial presence in northern Egypt.[31] The site of Buto in particular was suggested, but it has been rejected as a possible candidate.[26]

The fact that so many Gerzean sites are at the mouths of wadis which lead to the Red Sea may indicate some amount of trade via the Red Sea (though Byblian trade potentially could have crossed the Sinai and then be taken to the Red Sea).[32] Also, it is considered unlikely that something as complicated as recessed panel architecture could have worked its way into Egypt by proxy, and a possibly significant contingent of Mesopotamian migrants or settlers is often suspected.[1]

These early contacts probably acted as a sort of catalyst for the development of Egyptian culture, particularly in respect to the inception of writing, the codification of royal and vernacular imagery and architectural innovations.[2]

-

Egyptian palettes, such as the Narmer Palette (3200–3000 BC), borrow elements of Mesopotamian iconography, in particular the sauropod design of Uruk.[33]

-

Beads of lapis lazuli and travertine, circa 3650 –3100 BCE. Naqada II–Naqada III.

Importance of local Egyptian developments

While there is clear evidence the

Although there are many examples of Mesopotamian influence in Egypt in the 4th millennium BCE, the reverse is not true, and there are no traces of Egyptian influence in Mesopotamia at any time, clearly indicating a one way flow of ideas.

Early Egyptologists such as Flinders Petrie were proponents of the Dynastic race theory which hypothesised that the first Egyptian chieftains and rulers were themselves of Mesopotamian origin,[44] but this view has been abandoned among modern scholars.[45][46]

The current position of modern scholarship is that the Egyptian civilization was an indigenous Nile Valley development and that the archaeological evidence "strongly supports an African origin"[47] of the ancient Egyptians.[45][48][49][50]

Development of writing (3500–3200 BCE)

It is generally thought that

Standard reconstructions of the

There is however a lack of direct evidence that Mesopotamian writing influenced Egyptian form, and "no definitive determination has been made as to the origin of hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt".[57] Some scholars point out that "a very credible argument can also be made for the independent development of writing in Egypt..."[58] Since the 1990s, the discovery of glyphs on clay tags at Abydos, dated to between 3400 and 3200 BCE, may challenge the classical notion according to which the Mesopotamian symbol system predates the Egyptian one,[59][60][61] although perhaps tellingly, Egyptian writing does make a 'sudden' appearance at that time with no antecedents or precursors, while on the contrary Mesopotamia already had a long evolutionary history of sign usage in tokens dating back to circa 8000 BCE, followed by Proto-Cuneiform.[62][15] Pittman proposes that the Abydos clay tags are almost identical to contemporary clay tags from Uruk, Mesopotamia.[63]

Egyptian scholar Gamal Mokhtar argued that the inventory of hieroglyphic symbols derived from "fauna and flora used in the signs [which] are essentially African" and in "regards to writing, we have seen that a purely Nilotic, hence African origin not only is not excluded, but probably reflects the reality" although he acknowledged the geographical location of Egypt made it a receptacle for many influences.

-

Tablet with Mesopotamian proto-cuneiform pictographic characters (end of 4th millennium BC), Uruk III.

-

Mesopotamian pierced label, with symbol "EN" meaning "Master", the reverse of the plaque has the symbol for Goddess Inanna. Uruk circa 3000 BC. Louvre Museum AO 7702

-

Labels with some of the earliest Egyptian hieroglyphs from the tomb of Egyptian king Menes (3200–3000 BC)

-

Ivory plaque of Menes (3200–3000 BC)

2017 DNA Genome Study

A 2017 study of the

Overall the mummies studied were closer genetically to near easterners than the modern Egyptian or indeed nearby

The data suggest a very high level of genetic input from

The study stated that "our genetic time transect suggests genetic continuity between the Pre-Ptolemaic, Ptolemaic and Roman populations of Abusir el-Meleq, indicating that foreign rule impacted the [native] population only to a very limited degree at the genetic level."

The study's authors cautioned that the mummies may be unrepresentative of the Ancient Egyptian population as a whole.[72]

Gourdine, Anselin and Keita criticised the methodology of the Scheunemann et al. study and argued that the Sub-Saharan "genetic affinities" may be attributed to "early settlers" and "the relevant Sub-Saharan genetic markers" do not correspond with the geography of known trade routes".[73]

In 2022, Danielle Candelora noted several limitations with the 2017 Scheunemann et al. study such as its “untested sampling methods, small sample size and problematic comparative data” which she argued had been misused to legitimise racist conceptions of Ancient Egypt with “scientific evidence”[74]

Because the 2017 study only sampled from a single site at Abusir el-Meleq, Scheunemann et al.(2022) carried out a follow-up study by collecting samples from six different excavation sites along the entire length of the Nile Valley, spanning 4000 years of Egyptian history. 81 samples were collected from 17 mummies and 14 skeletal remains, and 18 high quality mitochondrial genomes were reconstructed from 10 individuals. The authors argued the analyzed mitochondrial genomes supported the results from the earlier study at Abusir el-Meleq.[75]

In 2023,

Egyptian influence on Mesopotamian art

After this early period of exchange, and the direct introduction of Mesopotamian components into Egyptian culture, Egypt soon started to assert its own style from the

Egypt seems to have provided some artistic feedback to Mesopotamia at the time of the

There is also a possibility that the depictions of the Mesopotamian king with a muscular, naked, upper body fighting his enemies in a quadrangular posture, as seen in the

Later periods

Trade of Indus goods through Mesopotamia

Etched carnelian beads

Rare

Hyksos period

Egypt records various exchanges with Semitic West Asian foreigners from around 1900 BCE, as in the paintings of the tomb of

From circa 1650 BCE, the

Exchanges would again flourish between the two cultures from the period of the

Neo-Assyrian Empire

In the last phase of historic exchanges during the

The Egyptian 26th Dynasty had been installed in 663 BC as native puppet rulers by the Assyrians after the destruction and deportation of the foreign Nubians of the 25th Dynasty by king Esarhaddon and then came under the dominion of his successors Ashurbanipal. However, during the fall of the Neo Assyrian Empire between 612 and 599 BC, Egypt attempted to aid its former masters probably due to the fear that without a strong Assyrian buffer they too would be overrun, having already been raided by marauding Scythians. As a result, Egypt came into conflict with Assyria's fellow Mesopotamian state of Babylonia, which along with the Medes, Persians, Chaldeans, Cimmerians and Scythians, amongst others, were fighting to throw off Assyrian rule, and Pharaoh Necho II fought alongside the last Assyrian emperor Ashur-uballit II (612-c.605 BC) against Nabopolassar, Cyaxares and their allies for a time. After the Assyrian Empire fell, Egypt engaged in a number of conflicts with Babylonia during the late 7th and early 6th century BC in the Levant, before being driven from the region by Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylonia.

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire, though Iranic and not Mesopotamian, was heavily influenced by Mesopotamia in its art, architecture, written script and civil administration, the Persians having previously been subjects of Assyria for centuries, invaded Egypt and established satrapies, founding the Achaemenid Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt (525–404 BCE) and Thirty-first Dynasty of Egypt (343–332 BCE).

-

Egyptian statue ofDarius I

-

Darius as Pharaoh of Egypt at the Temple of Hibis

-

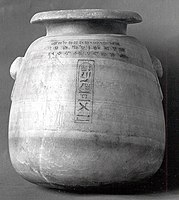

Jar of Xerxes I, with his name in hieroglyphs and cuneiform

See also

- Indus–Mesopotamia relations

- Ancient Egypt

- Fertile Crescent

- Mesopotamia

- Neolithic Revolution

- Sumer

- Assyria

- Babylonia

- Archaeogenetics of the Near East

References

- ^ a b c d Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 22.

- ^ ISBN 9781444333503.

- ^ a b Shaw, Ian. & Nicholson, Paul, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, (London: British Museum Press, 1995), p. 109.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Larkin. "Earliest Egyptian Glyphs". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ISBN 9780931464966.

- ^ ISBN 9781444333503.

- ^ ISBN 9780931464966.

- ^ ISBN 9780931464966.

- ISBN 9781444342345.

- ISBN 9780520203075.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 16.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- ^ ISBN 9780521251037.

- ^ ISBN 9781317296089.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8061-3342-3.

- ^ S2CID 161166931.

- ISBN 978-0-8061-3342-3.

- ^ a b c Honoré, Emmanuelle (January 2007). "Earliest Cylinder-Seal Glyptic in Egypt: From Greater Mesopotamia to Naqada". H. Hanna Ed., Preprints of the International Conference on Heritage of Naqada and Qus Region, Volume I.

- ^ ISBN 9781444342345.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 18.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 17.

- ISBN 9780931464966.

- ISBN 9780931464966.

- ISBN 978-0-292-75242-9.

- ^ ISBN 9781444342345.

- ISBN 978-0-19-973578-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-429-96199-1.

- ISBN 978-1-60606-444-3.

- ISBN 9780931464966.

- ^ ISBN 9780931464966.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 20.

- ISBN 0-203-20421-2.

- ^ "British Museum notice". 23 January 2020.

- ^ "Necklace British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ "Pendant British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ Miroschedji, Pierre de. Une palette égyptienne prédynastique du sud de la plaine côtière d'Israël.

- ^ Early Dynastic Egypt (Routledge, 1999), p.15

- ^ Redford, Donald B., Egypt, Israel, and Canaan in Ancient Times (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 13.

- ^ Gardiner, Alan. Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1961), p. 392.

- ^ Shaw, Ian. and Nicholson, Paul, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (London: British Museum Press, 1995), p. 228.

- ^ "Because the reverse is not true, namely there is no trace of an Egyptian presence in Mesopotamia at that time, all seems to point to a flow of ideas from Mesopotamia to Egypt." "Earliest Egyptian Glyphs – Archaeology Magazine Archive". archive.archaeology.org.

- ^ Louvre Museum AO 5359 Miroschedji, Pierre de. Une palette égyptienne prédynastique du sud de la plaine côtière d'Israël.

- S2CID 194596267.

- ^ ISBN 0415186331.

- ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ Smith, Stuart Tyson (2001). Redford, Donald (ed.). The Oxford encyclopedia of ancient Egypt. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. pp. 27–28.

- ISBN 0807845558.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (2003). Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state. Highfield, Southampton: Department of Archaeology, University of Southampton.

- ISBN 0936260645.

- ^ ISBN 9780723003045.

- ISBN 9780803291676.

- ISBN 9780521838610.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-1756-4. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-8028-3784-4. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards, et al., The Cambridge Ancient History (3d ed. 1970) pp. 43–44.

- ISBN 978-0-313-31342-4. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Simson Najovits, Egypt, Trunk of the Tree: A Modern Survey of an Ancient Land, Algora Publishing, 2004, pp. 55–56.

- ^ "And recent finds at Abydos that have pushed back the date of writing in Egypt, making it contemporaneous with the Mesopotamian invention, further undermine the old assumption that writing arose in Egypt under Sumerian influence."Woods, Christopher (2010). Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond. Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. p. 16.

- ^ "“The world’s earliest known writing systems emerged at more or less the same time, around 3300 bc, in Egypt and Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq).”"Teeter, Emily (2011). Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization. Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. p. 99.

- ISBN 9781139486354.

- ^ a b "The seal impressions, from various tombs, date even further back, to 3400 B.C. These dates challenge the commonly held belief that early logographs, pictographic symbols representing a specific place, object, or quantity, first evolved into more complex phonetic symbols in Mesopotamia." Mitchell, Larkin. "Earliest Egyptian Glyphs". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ISBN 9780931464966.

- ISBN 0852550928.

- ISBN 0-936260-64-5.

- ISBN 9780931464966.

- PMID 28556824.

- ^ a b Page, Thomas (22 June 2017). "DNA discovery unlocks secrets of ancient Egyptians". CNN.

- ^ PMID 28556824.

- ^ PMID 28556824.

- PMID 28556824.

- PMID 28556824.

- ISBN 978-0-521-84067-5.

- ISBN 9780367434632.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ "Human mitochondrial haplogroups and ancient DNA preservation across Egyptian history (Urban et al. 2021)" (PDF). ISBA9, 9th International Symposium on Biomolecular Archaeology, p.126. 2021.

In a previous study, we assessed the genetic history of a single site: Abusir el-Meleq from 1388 BCE to 426 CE. We now focus on widening the geographic scope to give a general overview of the population genetic background, focusing on mitochondrial haplogroups present among the whole Egyptian Nile River Valley. We collected 81 tooth, hair, bone, and soft tissue samples from 14 mummies and 17 skeletal remains. The samples span approximately 4000 years of Egyptian history and originate from six different excavation sites covering the whole length of the Egyptian Nile River Valley. NGS 127 based ancient DNA 8 were applied to reconstruct 18 high-quality mitochondrial genomes from 10 different individuals. The determined mitochondrial haplogroups match the results from our Abusir el-Meleq study.

- ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9. Archivedfrom the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-691-24410-5.

- ^ ISBN 9781444333503.

- ISBN 9781444333503.

- ISBN 9781444333503.

- JSTOR 43553796.

- ISBN 9781910634042.

- ISBN 9781405160704.

- ^ Bard 2015, p. 188.

- S2CID 199601200.

- ISBN 978-1-4051-6070-4.

- ISBN 978-1-118-89611-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4070-1092-2.

- ISBN 978-1-108-08291-4.

- ^ "Statue British Museum". The British Museum.

- ISBN 978-0-14-012523-8.

- ^ "The Late period (664–332 BCE)".

![Egyptian palettes, such as the Narmer Palette (3200–3000 BC), borrow elements of Mesopotamian iconography, in particular the sauropod design of Uruk.[33]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/be/Narmer_Palette.jpg/200px-Narmer_Palette.jpg)

![Egyptian statuette, 3300–3000 BC. The lapis lazuli material is thought to have been imported through Mesopotamia from Afghanistan. Ashmolean.[20][14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8a/Egypt_Lapis_lazuli_woman_%28detail%29.jpg/101px-Egypt_Lapis_lazuli_woman_%28detail%29.jpg)

![Egyptian necklace and pendant, using lapis lazuli imported from Afghanistan, possibly by Mesopotamian traders, Naqada II circa 3500 BCE, British Museum EA57765 EA57586.[34][35][36]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f1/Egyptian_necklace_and_piece_of_jewelry_with_lapis_lazuri_imported_from_Afghanistan%2C_possibly_by_Mesopotamian_traders%2C_Naqada_II_circa_3500_BCE%2C_British_Museum_EA57765_EA57586.jpg/133px-thumbnail.jpg)

![Designs on some of the labels or token from Abydos, Egypt, carbon-dated to circa 3400–3200 BC.[15][62] They are virtually identical with contemporary clay tags from Uruk, Mesopotamia.[66]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Design_of_the_Abydos_token_glyphs_dated_to_3400-3200_BCE.jpg/150px-Design_of_the_Abydos_token_glyphs_dated_to_3400-3200_BCE.jpg)