Einkorn wheat

| Einkorn wheat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pooideae |

| Genus: | Triticum |

| Species: | T. monococcum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Triticum monococcum | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Triticum monococcum subsp. monococcum | |

| Wild einkorn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pooideae |

| Genus: | Triticum |

| Species: | T. boeoticum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Triticum boeoticum | |

| Synonyms | |

Einkorn wheat (from German Einkorn, literally "single grain") can refer either to a wild species of

Einkorn wheat was one of the first plants to be

History

Einkorn wheat commonly grows wild in the hill country in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent and Anatolia although it has a wider distribution reaching into the Balkans and south to Jordan near the Dead Sea. It is a short variety of wild wheat, usually less than 70 centimetres (28 in) tall and is not very productive of edible seeds.[citation needed]

The principal difference between wild einkorn and cultivated einkorn is the method of seed dispersal. In the wild variety the seed head usually shatters and drops the kernels (seeds) of wheat onto the ground.[1] This facilitates a new crop of wheat. In the domestic variety, the seed head remains intact. While such a mutation may occasionally occur in the wild, it is not viable there in the long term: the intact seed head will only drop to the ground when the stalk rots, and the kernels will not scatter but form a tight clump which inhibits germination and makes the mutant seedlings susceptible to disease. But harvesting einkorn with intact seed heads was easier for early human harvesters, who could then manually break apart the seed heads and scatter any kernels not eaten. Over time and through selection, conscious or unconscious, the human preference for intact seed heads created the domestic variety, which also has slightly larger kernels than wild einkorn. Domesticated einkorn thus requires human planting and harvesting for its continuing existence.[5] This process of domestication might have taken only 20 to 200 years with the end product a wheat easier for humans to harvest.[6]

Einkorn wheat is one of the

An important characteristic facilitating the domestication of einkorn and other annual grains is that the plants are largely self-pollinating. Thus, the desirable (for human management) traits of einkorn could be perpetuated at less risk of cross-fertilization with wild plants which might have traits – e.g. smaller seeds, shattering seed heads,[1] as less desirable for human management.[13]

From the northern part of the Fertile Crescent, the cultivation of einkorn wheat spread to the

Taxonomy

- Triticum boeoticum

- syn.Triticum monococcum subsp. boeoticum (wild)

- Triticum monococcum

- domesticated)

Einkorn vs. common modern wheat varieties

Einkorn wheat is low-yielding but can survive on poor, dry, marginal soils where other varieties of wheat will not. It is primarily eaten boiled in whole grains or in porridge.[14] As with other ancient varieties of wheat, Einkorn is grouped with "the covered wheats" as its kernels do not break free from its seed coat (glume) with threshing and it is, therefore, difficult to separate the husk from the seed.[15]

Current use

Einkorn is a common food in northern

Nutrition and gluten

Einkorn contains

Genetics

Disease resistance

Einkorn is the source of many potential introgressions for immunity –

Salt-tolerance gene

The salt-tolerance feature of T. monococcum has been bred into durum wheat.[20]

Images

-

MHNT

-

Wild einkorn, Mount Karadağ

-

Associations of wild cereals and other wild grasses in northern Israel

-

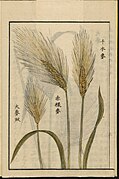

T. monococcum, Japanese agricultural encyclopedia Seikei Zusetsu (1804)

References

- ^ PMID 19100651.

- .

- ^ "5,300 Years Ago, Ötzi t'he Iceman Died. Now We Know His Last Meal". Science & Innovation. National Geographic. 2018-07-12. Archived from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved 2019-07-31.

- ^ Weiss and Zohary, p. S239-S242

- ^ Anderson, Patricia C. (1991). "Harvesting of Wild Cereals During the Natufian as seen from Experimental Cultivation and Harvest of Wild Einkorn Wheat and Microwear Analysis of Stone Tools". In Bar-Yosef, Ofer (ed.). Natufian Culture in the Levant. International Monographs in Prehistory. Ann Arbor, Michigan, US: Berghahn Books. p. 523.

- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi:10.1073/pnas.1801071115

- ^ "Crops evolving ten millennia before experts thought". ScienceDaily. 23 October 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- PMID 29061901.

- ISBN 9780199549061.

- .

- OCLC 896791508.

- ^ Bellwood, Peter (2005). First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 46-49.

- ^ ISBN 0-19-850356-3.

- ^ a b c Stallknecht, G. F., Gilbertson, K. M., and Ranney, J.E. (1996), "Alternative Wheat Cereals as Food Grains: Einkorn, Emmer, Spelt, Kamut, and Triticale" in J. Janick, ed., Progress in New Crops, Alexandria, VA: ASHA Press, pp. 156-170

- ISBN 978-2-84221-283-4.

- S2CID 16551824.

- OCLC 26827677.

- S2CID 252973250.

- ^ "World Breakthrough On Salt-Tolerant Wheat". ScienceDaily. March 11, 2012.