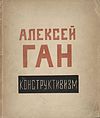

El Lissitzky

El Lissitzky | |

|---|---|

Russian SFSR, Soviet Union | |

| Occupation | Artist |

| Signature | |

| |

Lazar Markovich Lissitzky (Russian: Ла́зарь Ма́ркович Лиси́цкий,

Lissitzky's entire career was laced with the belief that the artist could be an agent for change, later summarized with his edict, "das zielbewußte Schaffen" (goal-oriented creation).

Early years

Lissitzky was born on 23 November 1890 in

Like many other Jews then living in the Russian Empire, Lissitzky went to study in Germany. He left in 1909 to study

Upon his return to Moscow, Lissitzky attended the

His first designs appeared in the 1917 book, Sihas hulin: Eyne fun di geshikhten (An Everyday Conversation), where he incorporated Hebrew letters with a distinctly

Avant-garde

Suprematism

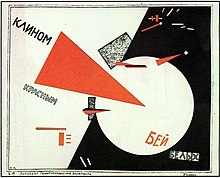

In May 1919,[3] upon receiving an invitation from fellow Jewish artist Marc Chagall, Lissitzky returned to Vitebsk to teach graphic arts, printing, and architecture at the newly formed People's Art School – a school that Chagall created after being appointed Commissioner of Artistic Affairs for Vitebsk in 1918. Lissitzky was engaged in designing and printing propaganda posters; later, he preferred to keep quiet about this period, probably because one of main subjects of these posters was the exile Leon Trotsky.[11] The quantity of these posters is sufficient to regard them as a separate genre in the artist's output.[12]

Chagall also invited other Russian artists, most notably the painter and art theoretician Kazimir Malevich and Lissitzky's former teacher, Yehuda Pen. However, it was not until October 1919 when Lissitzky, then on an errand in Moscow, persuaded Malevich to relocate to Vitebsk.[13] The move coincided with the opening of the first art exhibition in Vitebsk directed by Chagall.[14] Malevich would bring with him a wealth of new ideas, most of which inspired Lissitzky but clashed with local public and professionals who favored figurative art and with Chagall himself.[15] After going through impressionism, primitivism, and cubism, Malevich began developing and advocating his ideas on suprematism aggressively. In development since 1915, suprematism rejected the imitation of natural shapes and focused more on the creation of distinct, geometric forms. He replaced the classic teaching program with his own and disseminated his suprematist theories and techniques school-wide. Chagall advocated more classical ideals and Lissitzky, still loyal to Chagall, became torn between two opposing artistic paths. Lissitzky ultimately favoured Malevich's suprematism and broke away from traditional Jewish art. Chagall left the school shortly thereafter.

At this point Lissitzky subscribed fully to suprematism and, under the guidance of Malevich, helped further develop the movement. In 1919–1920 Lissitzky was a head of Architectural department at the People's Art School where with his students, primarily Lazar Khidekel, he was working on transition from plane to volumetric suprematism.

On 17 January 1920,

The group, which disbanded in 1922, would be pivotal in the dissemination of suprematist ideology in Russia and abroad and launch Lissitzky's status as one of the leading figures in the avant garde. Incidentally, the earliest appearance of the signature Lissitzky (Russian: Эль Лисицкий) emerged in the handmade UNOVIS Miscellany, issued in two copies in March–April 1920,[24] and containing his manifesto on book art: "the book enters the skull through the eye not the ear therefore the pathways the waves move at much greater speed and with more intensity. if i (sic) can only sing through my mouth with a book i (sic) can show myself in various guises."[25]

Proun

During this period Lissitzky proceeded to develop a suprematist style of his own, a series of abstract, geometric paintings which he called Proun (pronounced "pro-oon"). The exact meaning of "Proun" was never fully revealed, with some suggesting that it is a contraction of proekt unovisa (designed by UNOVIS) or proekt utverzhdenya novogo (Russian: проект утверждения нового; 'Design for the confirmation of the new'). Later, Lissitzky defined them ambiguously as "the station where one changes from painting to architecture."[4]

Proun was essentially Lissitzky's exploration of the visual language of suprematism with

Return to Germany

In 1921, roughly concurrent with the demise of UNOVIS, suprematism was beginning to fracture into two ideologically adverse halves, one favoring Utopian, spiritual art and the other a more utilitarian art that served society. Lissitzky was fully aligned with neither and left Vitebsk in 1921. He took a job as a cultural representative of Russia and moved to Berlin where he was to establish contacts between Russian and German artists. There he also took up work as a writer and designer for international magazines and journals while helping to promote the avant-garde through various gallery shows. He started the very short-lived but impressive periodical Veshch-Gegenstand Objekt with Russian-Jewish writer Ilya Ehrenburg. This was intended to display contemporary Russian art to Western Europe. It was a wide-ranging pan-arts publication, mainly focusing on new suprematist and constructivist works, and was published in German, French and Russian.[26] In the first issue, Lissitzky wrote:

We consider the triumph of the constructive method to be essential for our present. We find it not only in the new economy and in the development of the industry, but also in the psychology of our contemporaries of art. Veshch will champion constructive art, whose mission is not, after all, to embellish life, but to organize it.[2]

During his stay Lissitzky also developed his career as a

Horizontal skyscrapers

In 1923–1925, Lissitzky proposed and developed the idea of horizontal skyscrapers (Wolkenbügel, "cloud-hangers", "sky-hangers" or "sky-hooks"). A series of eight such structures was intended to mark the major intersections of the Boulevard Ring in Moscow. Each Wolkenbügel was a flat three-story, 180-meter-wide L-shaped slab raised 50 meters above street level. It rested on three pylons (10×16×50 meters each), placed on three different street corners. One pylon extended underground, doubling as the staircase into a proposed subway station; two others provided shelter for ground-level tram stations.[28][29]

Lissitzky argued that as long as humans cannot fly, moving horizontally is natural and moving vertically is not. Thus, where there is not sufficient land for construction, a new plane created in the air at medium altitude should be preferred to an American-style tower. These buildings, according to Lissitzky, also provided superior insulation and ventilation for their inhabitants.[30]

Lissitzky, aware of severe mismatch between his ideas and the existing urban landscape, experimented with different configurations of the horizontal surface and height-to-width ratios so that the structure appeared balanced visually ("spatial balance is in the contrast of vertical and horizontal tensions").[30] The raised platform was shaped in a way that each of its four facets looked distinctly different. Each tower faced the Kremlin with the same facet, providing a pointing arrow to pedestrians on the streets. All eight buildings were planned identically, so Lissitzky proposed color-coding them for easier orientation.[31]

After some time of creating "paper architecture" projects such as the Wolkenbügels he was hired to design an actual building in Moscow. Located at 55°46′38″N 37°36′39″E / 55.777277°N 37.610828°E 17, 1st Samotechny Lane, it is Lissitzky's sole tangible work of architecture. It was commissioned in 1932 by

Exhibitions of the 1920s

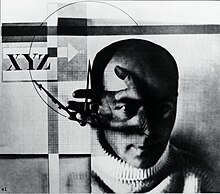

After two years of intensive work Lissitzky was taken ill with acute pneumonia in October 1923. A few weeks later he was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis; in February 1924 he relocated to a Swiss sanatorium near Locarno.[33] He kept very busy during his stay, working on advertisement designs for Pelikan Industries (who in turn paid for his treatment), translating articles written by Malevich into German, and experimenting heavily in typographic design and photography. In 1925, after the Swiss government denied his request to renew his visa, Lissitzky returned to Moscow and began teaching interior design, metalwork, and architecture at Vkhutemas (State Higher Artistic and Technical Workshops), a post he would keep until 1930. He all but stopped his Proun works and became increasingly active in architecture and propaganda designs.

In June 1926, Lissitzky left the country again, this time for a brief stay in Germany and the Netherlands. There he designed an exhibition room for the Internationale Kunstausstellung art show in Dresden and the Raum Konstruktive Kunst ('Room for constructivist art') and Abstraktes Kabinett shows in Hanover, and perfected the 1925 Wolkenbügel concept in collaboration with Mart Stam.[33] In his autobiography (written in June 1941, and later edited and released by his wife), Lissitzky wrote, "1926. My most important work as an artist begins: the creation of exhibitions."[4]

In 1926, Lissitzky joined Nikolai Ladovsky's Association of New Architects (ASNOVA) and designed the only issue of the association's journal Izvestiia ASNOVA (News of ASNOVA) in 1926.

Back in the USSR, Lissitzky designed displays for the official Soviet pavilions at the international exhibitions of the period, up to the 1939 New York World's Fair. One of his most notable exhibits was the All-Union Polygraphic Exhibit in Moscow in August–October 1927, where Lissitzky headed the design team for "photography and photomechanics" (i.e. photomontage) artists and the installation crew.[34] His work was perceived as radically new, especially when juxtaposed with the classicist designs of Vladimir Favorsky (head of the book art section of the same exhibition) and of the foreign exhibits.

In the beginning of 1928, Lissitzky visited Cologne in preparation for the 1928 Pressa Show scheduled for April–May 1928. The state delegated Lissitzky to supervise the Soviet program; instead of building their own pavilion, the Soviets rented the existing central pavilion, the largest building on the fairground. To make full use of it, the Soviet program designed by Lissitsky revolved around the theme of a film show, with nearly continuous presentation of the new feature films, propagandist newsreels and early animation, on multiple screens inside the pavilion and on the open-air screens.[35] His work was praised for near absence of paper exhibits; "everything moves, rotates, everything is energized" (Russian: всё движется, заводится, электрифицируется).[36] Lissitzky also designed and managed on site less demanding exhibitions like the 1930 Hygiene show in Dresden.[37]

Along with pavilion design, Lissitzky began experimenting with print media again. His work with book and periodical design was perhaps some of his most accomplished and influential. He launched radical innovations in typography and photomontage, two fields in which he was particularly adept. He even designed a photomontage birth announcement in 1930 for his recently born son, Jen. The image itself is seen as being another personal endorsement of the Soviet Union,[8] as it superimposed an image of the infant Jen over a factory chimney, linking Jen's future with his country's industrial progress. Around this time, Lissitzky's interest in book design escalated. In his remaining years, some of his most challenging and innovative works in this field would develop. In discussing his vision of the book, he wrote:

In contrast to the old monumental art [the book] itself goes to the people, and does not stand like a cathedral in one place waiting for someone to approach ... [The book is the] monument of the future.[2]

He perceived books as permanent objects that were invested with power. This power was unique in that it could transmit ideas to people of different times, cultures, and interests, and do so in ways other art forms could not. This ambition laced all of his work, particularly in his later years. Lissitzky was devoted to the idea of creating art with power and purpose, art that could invoke change.

Later years

In 1932, Stalin closed down independent artists' unions; former avant-garde artists had to adapt to the new climate or risk being officially criticised or even blacklisted. Lissitzky retained his reputation as the master of exhibition art and management into the late 1930s. His tuberculosis gradually reduced his physical abilities, and he was becoming more and more dependent on his wife in actual completion of his work.[38]

In 1937, Lissitzky served as the lead decorator for the upcoming

In June 1938, he was only one of seventeen professionals and managers responsible for the Central Pavilion;[40] in October 1938, he shared the responsibility for its Main Hall decoration with Vladimir Akhmetyev.[41] He simultaneously worked on the decoration of the Soviet pavilion for the 1939 New York World's Fair; the June 1938 commission considered Lissitzky's work along with nineteen other proposals and eventually rejected it.[42]

Lissitzky's work on the USSR in Construction magazine took his experimentation and innovation with book design to an extreme. In issue #2 he included multiple fold-out pages, presented in concert with other folded pages that together produced design combinations and a narrative structure that was completely original. Each issue focused on a particular issue of the time – a new dam being built, constitutional reforms, Red Army progress and so on. In 1941, his tuberculosis worsened, but he continued to produce works, one of his last being a propaganda poster for Russia's efforts in World War II, titled "Davaite pobolshe tankov!" (Give us more tanks!). He died on 30 December 1941, in Moscow.[43]

Notes

- ^ a b c Curl

- ^ a b c d Glazova

- ^ a b Shatskikh, 57

- ^ a b c Lissitzky-Kuppers

- ^ Schatskikh, p.58

- ^ a b Spencer, Poynor, 2004:69

- ^ Margolin (1997), p.24

- ^ a b c d Perloff 2005

- ^ Margolin (2000)

- ^ Self-Portrait: Constructor. Victoria & Albert Museum, 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Shatskikh, 62

- ^ Shatskikh, 63

- ^ Shatskikh, 66

- ^ Shatskikh, 70

- ^ Shatskikh, 71

- ^ S. Khan-Magomedov. Lazar Khidekel. The Russian Avant-garde Foundation, 2011

- ^ Shatskikh, 78–79

- ^ Tupitsyn, 9

- ^ Shatskikh, 92

- ^ a b Shatskikh, 93

- ^ Malgrave, 239

- ^ The opera was produced without original orchestral music – Shatskikh, 98

- ^ Shatskikh, 111

- ^ Shatskikh, 125

- ^ Shatskikh, 122

- ^ a b Malgrave, 250

- ^ Malgrave, 243

- ^ Khan-Magomedov, 213

- ^ Balandin

- ^ a b Khan-Magomedov, 215

- ^ Khan-Magomedov, 216

- ^ Ilyicheva

- ^ a b Spencer, Poynor, 70

- ^ Tolstoy, 57–58 provides verbatim copies of relevant government decrees dated June 1927.

- ^ Tolstoy, 123–125

- ^ Tolstoy, 127

- ^ Tolstoy, 144

- ^ Tupitsyn

- ^ a b Tolsoy, 172–174, cites verbatim a report signed by Lissitzky 20 October 1937

- ^ Tolstoy, 185

- ^ Tolstoy, 189

- ^ Tolstoy, 400–403

- ^ "El Lissitzky". Guggenheim. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

References

- ISBN 978-3-933713-63-6

- Balandin, S. N. (1968). "Arkhitekturnaya teoriya El Lisitskogo (Архитектурная теория Эль Лисицкого)" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- Burgos, Francisco; Garrido, Gines (2004). El Lissitzky. Wolkenbugel 1924–1925. Absent Architecture (Rueda, Spain). ISBN 978-84-7207-158-2.

- Curl, James Stevens (2006). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Paperback) (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860678-8.

- Glazova, Anna (2003). "El Lissitzky in Weimar Germany". Speaking in Tongues. The Magazine of Literary Tran slation. Archived from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- Khan-Magomedov, S. O. (2005). Sto shedevrov sovetskogo arkhitekturnogo avangarda (Сто шедевров советского архитектурного авангарда) (in Russian and Spanish). URSS, Moscow. ISBN 5-354-00892-1.

- Lissizky, El; Schwitters, Kurt (1924). "Merz (magazine) no. 8-9". Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- Lissitzky-Kuppers, Sophie (1980). El Lissitzky, life, letters, texts. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-23090-0.

- Mallgrave, Harry Francis (2005). Modern Architectural Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673-1968. Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-79306-8.

- Margolin, Victor (1997). The struggle for utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy: 1917–1946. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-50516-2.

- Margolin, Victor (2000). "El Lissitzky's Had Gadya, 1919" (PDF). Yeshiva University, New York. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir; El Lissitzky (2000). For the Voice (Dlia golosa). The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-13377-6.

- Perloff, Nancy; et al. (2005). "Design by El Lissitzky". Getty Research Institute. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- Perloff, Nancy; Reed, Brian (2003). Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, Moscow. Getty Research Institute. ISBN 0-89236-677-X.

- Spencer, Herbert; Poynor, Rick (2004). Pioneers of ISBN 978-0-262-69303-5.

- Shatskikh, Alexandra (2007). Vitebsk: The Life of Art. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10108-9.

- Shishanov V.A. Vitebsk Museum of Modern Art: a history of creation and a collection. 1918-1941. - Minsk: Medisont, 2007. - 144 p.[1] [2]

- Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum; El Lissitzy (1990). El Lissitzky, 1890–1941: Architect Painter Photographer Typographer. Municipal Van Abbemuseum. ISBN 90-70149-28-1.

- Tolstoy, V. P., ed. (2006). Vystavochnye ansambli SSSR 1920-1930-e gody (Выставочные ансамбли СССР в 1920-1930 годы, Exhibition ensembles of the USSR in the 1920s-1930s) (in Russian). Galart, Moscow. ISBN 978-5-269-01050-2.

- Tupitsyn, Margarita (1999). El Lissitzky: Beyond the Abstract Cabinet. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08170-1.

- El Lissitzky. Wolkenbügel 1924-1925. Publisher= Editorial Rueda, Madrid, 2005 ISBN 84-7207-158-8

External links

- Works by or about El Lissitzky at Internet Archive

- Ibiblio.org – Image collection of some of his most famous works

- MoMA – Flash-navigable exploration of USSR im bau and Dlia Golossa (click on "Reading Room" link)

- The Roland Collection of Films & Videos on Art – Free streaming download of an entire 88-minute documentary, El Lissitzky, by Leo Lorez

- A Factory Discography – Factory Records catalog by Dennis Remmer.

- Factory Benelux Discography – Factory Benelux section of the above website (scroll to FBN 24 to see The Wake).

- FAC 101 to FAC 150 – Portion of Remmer's Factory catalog that contains FACT 130.

- The full text of NASCI (Merz No. 8/9, Hanover, April–July 1924).

- Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven image collection of El Lissizky

- MT Abraham Foundation El Lissizky at the MT Abraham Collection

- Valeri Shishanov. VITEBSK' BUDETLANE

- Catalogue listing for Swann Galleries auction of record-setting poster by Lissitzky.

- El Lissitzky. Suprematic tale about two squares Archived 31 January 2015 at archive.today

- El Lissitzky at IMDb