Elizabethan literature

| Reformation-era literature |

|---|

Elizabethan literature refers to bodies of work produced during the reign of

Historical context

Elizabeth I presided over a vigorous culture that saw notable accomplishments in the arts, voyages of discovery, the "

During her reign, a London-centred culture, both

Prose

Two of the most important Elizabethan prose writers were

George Puttenham (1529–1590) was a 16th-century English writer and literary critic. He is generally considered to be the author of the influential handbook on poetry and rhetoric, The Arte of English Poesie (1589).

Poetry

Italian literature was an important influence on the poetry of

In the later 16th century, English poetry was characterised by elaboration of language and extensive allusion to classical myths. The most important poets of this era include

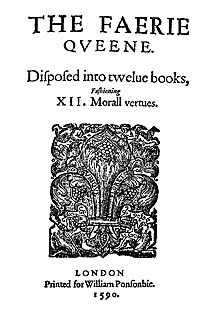

Edmund Spenser (c. 1552–99) was one of the most important poets of this period, author of

Shakespeare also popularised the English sonnet, which made significant changes to Petrarch's model.

Changes to the canon

While the canon of Renaissance English poetry of the 16th century has always been in some form of flux, it is only towards the late 20th century that concerted efforts were made to challenge the canon. Questions that once did not even have to be made, such as where to put the limitations of periods, what geographical areas to include, what genres to include, what writers and what kinds of writers to include, are now central.

The central figures of the Elizabethan canon are Spenser, Sidney, Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare, and Ben Jonson. There have been few attempts to change this long established list because the cultural importance of these five is so great that even re-evaluations on grounds of literary merit have not dared to dislodge them from the curriculum. Spenser, for example, had a significant influence on 17th-century poetry and was the primary English influence on John Milton.[citation needed]

In the 18th century, interest in Elizabethan poetry was rekindled through the scholarship of Thomas Warton and others.

The

In the 20th century

In 1939, American critic

Both Eliot and Winters[clarification needed] were much in favour of the established canon. Towards the end of the 20th century, however, the established canon was criticised, especially by those who wished to expand it to include, for example, more women writers.[16]

Theatre

The

During the reign of

Shakespeare's career continued into the

Other important figures in the

Marlowe's (1564–1593) subject matter is different from Shakespeare's as it focuses more on the moral drama of the Renaissance man than any other thing. Drawing on German folklore, Marlowe introduced the story of Faust to England in his play Doctor Faustus (c. 1592), about a scientist and magician who, obsessed by the thirst of knowledge and the desire to push man's technological power to its limits, sells his soul to the Devil. Faustus makes use of "the dramatic framework of the morality plays in its presentation of a story of temptation, fall, and damnation, and its free use of morality figures such as the good angel and the bad angel and the seven deadly sins, along with the devils Lucifer and Mephistopheles."[24]

Thomas Dekker (c. 1570–1632) was, between 1598 and 1602, involved in about forty plays, usually in collaboration. He is particularly remembered for The Shoemaker's Holiday (1599), a work where he appears to be the sole author. Dekker is noted for his "realistic portrayal of daily London life" and for "his sympathy for the poor and oppressed".[25]

List of other writers

List of other of the writers born in this period:

- John Donne (1572–1631)

- Ben Jonson (1572–1637)

- Thomas Middleton (1580–1627)

- John Webster (c. 1580–c. 1634)

See also

- English Renaissance theatre

- Jacobean literature

- Pamphlet wars

- Renaissance literature

References

- ^ "The Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I". Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "Elizabethan Literature". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Elizabeth I, Queen of England 1533–1603", Anthology of the British Literature, vol. A (concise ed.), Petersborough: Broadview, 2009, p. 683.

- ^ Frances Amelia Yates (1934). John Florio: The Life of an Italian in Shakespeare's England. United Kingdom: University Press. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ISBN 0-14-070738-7;

- ^ "John Lilly and Shakespeare", by C. C. Hense in the Jahrbuch der deutschen Shakesp. Gesellschaft, vols. vii and viii (1872, 1873).

- ^ Nicholl, Charles (8 March 1990). "'Faustus' and the Politics of Magic". London Review of Books. pp. 18–19. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ John O'Connell (28 February 2008). "Sex and books: London's most erotic writers". Time Out. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ a b Tillyard 1929.

- ^ Burrow 2004.

- ^ Ward et al. 1907–21, p. 3.

- ^ The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Sixteenth/Early Seventeenth Century, Volume B, 2012, p. 647

- ^ Poetry, LII (1939, pp. 258–72, excerpted in Paul. J. Alpers (ed): Elizabethan Poetry. Modern Essays in Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

- ^ Poetry, LII (1939, pp. 258–72, excerpted in Paul. J. Alpers (ed): Elizabethan Poetry. Modern Essays in Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967: 98

- ^ Poetry, LII (1939, pp. 258–72, excerpted in Paul. J. Alpers (ed): Elizabethan Poetry. Modern Essays in Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967: 95

- ISBN 978-0582090965. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Buck, Claire, ed. "Lumley, Joanna Fitzalan (c. 1537–1576/77)." The Bloomsbury Guide to Women's Literature. New York: Prentice Hall, 1992. 764.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 235.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, pp. 353, 358; Shapiro 2005, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Bradley 1991, p. 85; Muir 2005, pp. 12–16.

- ^ Bradley 1991, pp. 40, 48.

- ^ Dowden 1881, p. 57.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, pp. 1247, 1279

- ^ Clifford, Leech. "Christopher Marlowe". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ The Oxford Companion to English Literature (1996), pp. 266–7.

Works cited

- ISBN 978-0-7493-8655-9.

- ISBN 978-0-14-053019-3.

- Burrow, Colin (2004). "Wyatt, Sir Thomas (c.1503–1542)". doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30111. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- OL 6461529M.

- ISBN 978-0-415-35325-0.

- ISBN 978-0-571-21480-8.

- Tillyard, E M W (1929), The Poetry of Sir Thomas Wyatt, A Selection and a Study, London: The Scholartis Press, ISBN 978-0-403-08614-6

- Ward, AW; Waller, AR; Trent, WP; Erskine, J; Sherman, SP; Van Doren, C, eds. (1907–21), History of English and American literature, New York: GP Putnam’s Sons University Press.

- ISBN 978-0-19-926717-0.