Emphysema

| Emphysema | |

|---|---|

lung volume reduction[4] | |

| Medication | Inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids[4] |

Emphysema is any air-filled enlargement in the body's tissues. and is also known as pulmonary emphysema.

Emphysema is a

When associated with significant airflow limitation, emphysema is a

There are four types of emphysema, three of which are related to the anatomy of the

Signs and symptoms

Emphysema is a respiratory disease of the

Early symptoms of emphysema may vary from person to person. Symptoms can include a cough (with or without sputum), wheezing, a fast breathing rate, breathlessness on exertion, and a feeling of tightness in the chest. There may be frequent cold or flu infections.[1] Other symptoms may include anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep problems and weight loss. These symptoms could also relate to other lung conditions or other health problems;[20] therefore, emphysema is often underdiagnosed.[citation needed] The shortness of breath caused by emphysema can increase over time and develop into chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

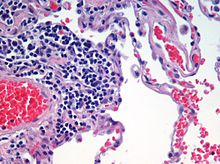

A sign of emphysema in smokers is the finding of a higher number of alveolar macrophages sampled from the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in the lungs. The number can be four to six times greater in those who smoke than in non-smokers.[21]

Emphysema is also associated with barrel chest.

Types

There are four main types of emphysema, three of which are related to the anatomy of the

Only the first two types of emphysema – centrilobular and panlobular – are associated with significant airflow obstruction, with that of centrilobular emphysema around 20 times more common than panlobular.[16] The subtypes can be seen on imaging but are not well-defined clinically.[17] There are also a number of associated conditions including bullous emphysema, focal emphysema, and Ritalin lung.

Centrilobular

Centrilobular emphysema, also called centriacinar emphysema, affects the centre of a

Panlobular

Panlobular emphysema, also called panacinar emphysema, affects all of the alveoli in a lobule, and can involve the whole lung or mainly the lower lobes.

Complications

Likely complications of centrilobular and panlobular emphysema, some of which are life-threatening, include: respiratory failure, pneumonia, respiratory infections, pneumothorax, interstitial emphysema, pulmonary heart disease, and respiratory acidosis.[24]

Paraseptal

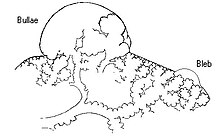

Paraseptal emphysema, also called distal acinar emphysema, relates to emphysematous change next to a

Bullous

When the subpleural bullae are significant, the emphysema is called bullous emphysema. Bullae can become extensive and combine to form giant bullae. These can be large enough to take up a third of a hemithorax, compress the lung parenchyma, and cause displacement. The emphysema is now termed giant bullous emphysema, more commonly called vanishing lung syndrome due to the compressed parenchyma.[27] A bleb or bulla may sometimes rupture and cause a pneumothorax.[16]

Paracicatricial

Paracicatricial emphysema, also known as irregular emphysema, is seen next to areas of

HIV associated

Classic lung diseases are a complication of HIV/AIDS with emphysema being a source of disease. HIV is cited as a risk factor for the development of emphysema and COPD regardless of smoking status.[29] Around 20 percent of those with HIV have increased emphysematous changes. This has suggested that an underlying mechanism related to HIV is a contributory factor in the development of emphysema. HIV associated emphysema occurs over a much shorter time than that associated with smoking; an earlier presentation is also seen in emphysema caused by alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Both of these conditions predominantly show damage in the lower lungs, which suggests a similarity between the two mechanisms.[30]

Emphysema may develop in some people with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, the only genotype of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This usually occurs a lot earlier (as does HIV associated emphysema) than other types.[31]

Ritalin lung

The intravenous use of

CPFE

Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE) is a rare syndrome that shows upper-lobe emphysema, together with lower-lobe interstitial fibrosis. This is diagnosed by CT scan.[33] This syndrome presents a marked susceptibility for the development of pulmonary hypertension.[34]

SRIF

Smoking-related interstitial fibrosis (SRIF) is another type of fibrosis that occurs in emphysematous lungs and can be identified by pathologists. Unlike CPFE, this type of fibrosis is usually clinically occult (i.e., does not cause symptoms or imaging abnormalities). Occasionally, however, some patients with SRIF present with symptoms and radiologic findings of interstitial lung disease.[35]

Congenital lobar

Congenital lobar emphysema (CLE), also known as congenital lobar overinflation and infantile lobar emphysema,

Focal

Focal emphysema is a localized region of emphysema in the lung that is larger than alveoli, and often associated with

Occupational

A number of occupations are associated with the development of emphysema due to the inhalation of varied gases and particles. In the US

The inhalation of

Ozone-induced emphysema

Ozone is another pollutant that can affect the respiratory system. Long-term exposure to ozone can result in emphysema.[45]

Osteoporosis

Other terms

Compensatory emphysema is overinflation of part of a lung in response to either removal by surgery of another part of the lung or decreased size of another part of the lung.[47]

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) is a collection of air inside the lungs but outside the normal air space of the alveoli, found as pneumatoses inside the connective tissue of the peribronchovascular sheaths, interlobular septa, and visceral pleura.

Lung volume reduction

Lung volume reduction may be offered to those with advanced emphysema. When other treatments fail, and the emphysema is located in the upper lobes, a surgical option may be possible.

Surgical

Where there is severe emphysema with significant hyperinflation that has proved unresponsive to other therapies,

Bronchoscopic

Minimally invasive bronchoscopic procedures may be carried out to reduce lung volume. These include the use of valves, coils, or thermal ablation.[53][54] Endobronchial valves are one-way valves that may be used in those with severe hyperinflation resulting from advanced emphysema; a suitable target lobe and no collateral ventilation are required for this procedure. The placement of one or more valves in the lobe induces a partial collapse of the lobe that ensures a reduction in residual volume that improves lung function, the capacity for exercise, and quality of life.[55]

The placement of endobronchial coils made of

Both of these techniques are associated with adverse effects, including persistent air leaks and cardiovascular complications. Bronchoscopic thermal vapor ablation has an improved profile. Heated water vapor is used to target affected lobe regions, which leads to permanent fibrosis and volume reduction. The procedure is able to target individual lobe segments, can be carried out regardless of collateral ventilation, and can be repeated with the natural advance of emphysema.[58]

Other surgeries

Lung transplantation – the replacement of either a single lung or both (bilateral) – may be considered in end-stage disease. A bilateral transplant is the preferred choice as complications can arise in a remaining single native lung; complications can include hyperinflation, pneumonia, and the development of lung cancer.[59] Careful selection as recommended by the National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) for transplant surgeries is needed as in some cases there will be an increased risk of mortality.[48] Several factors including age, and poor exercise tolerance, using the BODE index need to be taken into account.[59] A transplant is only considered where there are no serious comorbidites.[49] A CT scan or a ventilation/perfusion scan may be useful in surgery considerations to evaluate cases for surgical interventions, and also to evaluate post-surgery responses.[60] A bullectomy may be carried out when a giant bulla occupies more than a third of a hemithorax.[49]

In other tissues

Trapped air can also develop in other tissues such as under the skin, known as

History

The terms emphysema and chronic bronchitis were formally defined in 1959 at the CIBA guest symposium, and in 1962 at the American Thoracic Society Committee meeting on Diagnostic Standards.[63] The word emphysema is derived from Ancient Greek ἐμφύσημα 'inflation, swelling'[64] (referring to a lung inflated by air-filled spaces), itself from ἐμφυσάω emphysao 'to blow in, to inflate',[65] composed of ἐν en, meaning "in", and φυσᾶ physa,[66] meaning "wind, blast".[67][68]

References

- ^ a b c d e "Emphysema". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- ^ Gold Report 2021, pp. 20–23, Chapter 2: Diagnosis and initial assessment.

- ^ Gold Report 2021, pp. 33–35, Chapter 2: Diagnosis and initial assessment.

- ^ a b c Gold Report 2021, pp. 40–46, Chapter 3: Evidence supporting prevention and maintenance therapy.

- ^ a b "Definition of Emphysema". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ a b "ICD-11 – ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ISBN 9780071222075.

- ^ Murphy A, Danaher L. "Pulmonary emphysema". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Algusti AG, et al. (2017). "Definition and Overview". Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). pp. 6–17.

- .

- ^ Diedtra Henderson (2014-12-16). "Emphysema on CT Without COPD Predicts Higher Mortality Risk". Medscape.

- ^ "FastStats – Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease". www.cdc.gov. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ PMID 33313212.

- S2CID 59233744.

- ^ Coffey D (15 November 2022). "Buzz Kill: Lung Damage Looks Worse in Pot Smokers". Medscape.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kumar 2018, pp. 498–501.

- ^ PMID 24384106.

- ^ a b "COPD and comorbidities" (PDF). p. 133. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Global Strategy for Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of COPD: 2021 Report (PDF). 25 November 2020. p. 123. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Pulmonary Emphysema". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- PMID 30020685. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- PMID 18686729.

- ^ S2CID 239605521. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- PMID 29489292. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Chest". Radiology assistant. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Mosenifar Z (April 2019). "Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)". emedicine.medscape. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- S2CID 882767.

- ^ Weerakkody Y. "Paracicatricial emphysema | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- PMID 34285903.

- PMID 29351445.

- ^ "Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Sharma R. "Ritalin lung". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- PMID 29374870.

- PMID 24355635.

- PMID 36495281.

- ^ "UpToDate: Congenital lobar emphysema". Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ PMID 22595712.

- ^ PMID 31118601.

- ISBN 9780323523714.

- ^ Weerakkody Y. "Localised pulmonary emphysema | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ Gaillard F. "Pulmonary bullae | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ "Worker Health Study Summaries – Uranium Miners | NIOSH | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 15 June 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Pathology Basis of Occupational Lung Disease, Pneumoconiosis | NIOSH | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 5 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ "Pathology Basis of Occupational Lung Disease, Silicosis | NIOSH | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 5 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- PMID 31354743.

- PMID 22793940.

- ISBN 9789811316197.

- ^ S2CID 12014757.

- ^ S2CID 221145423.

- ^ Gold Report 2021, p. 96, Chapter 4: Management of stable COPD.

- S2CID 73428098.

- PMID 27739074.

- ^ Gold Report 2021, pp. 60–65, Chapter 3: Evidence supporting prevention and maintenance therapy.

- ^ "1 Recommendations | Endobronchial valve insertion to reduce lung volume in emphysema | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 20 December 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- PMID 33345947.

- PMID 29991060.

- PMID 30210833.

- S2CID 78181696. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ PMID 33313218.

- S2CID 56486118.

- PMID 8309261. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- PMID 31334970. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ PMID 18046898.

- ^ "Greek Word Study Tool – ἐμφύσημα". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ "Greek Word Study Tool". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ "Greek Word Study Tool". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ & Klein 1971, p. 245.

- ^ "Emphysema". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ a b Wright & Churg 2008, pp. 693–705.

Bibliography

- Klein E (1971). A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Elsevier Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-444-40930-0.

- Kumar V (2018). Robbins Basic Pathology. Elsevier. ISBN 9780323353175.

- Wright JL, Churg A (2008). "Pathologic Features of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Diagnostic Criteria and Differential Diagnosis" (PDF). In Fishman A, Elias J, Fishman J, Grippi M, Senior R, Pack A (eds.). Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-164109-8. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- "Gold report 2021" (PDF). Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2021.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. VIII (9th ed.). 1878. pp. 180–181.