Empire Theatre (42nd Street)

Eltinge Theatre, Laff-Movie, Empire Theatre | |

New 42nd Street | |

| Website | |

|---|---|

| www |

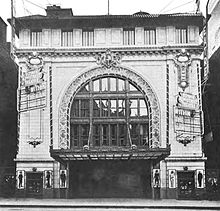

The Empire Theatre (originally the Eltinge Theatre) is a former Broadway theater at 234 West 42nd Street in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City. Opened in 1912, the theater was designed by Thomas W. Lamb for the Hungarian-born impresario A. H. Woods. It was originally named for female impersonator Julian Eltinge, a performer with whom Woods was associated. In 1998, the building was relocated 168 feet (51 m) west of its original location to serve as the entrance to the AMC Empire 25, a multiplex operated by AMC Theatres, which opened in April 2000.

The facade of the Empire Theatre is made of terracotta and is square in shape, with relatively little ornamentation compared to other theaters of the time. The center of the facade contains a three-story arch, which was intended to resemble a Roman triumphal arch; a fourth story was used for offices. The theater had about 900 seats in its auditorium, spread across three levels. It was decorated with ancient Egyptian and Greek details, as well as a sounding board depicting three dancing women. Most of the original detail was restored when the theater building was repurposed in 1998. The former auditorium serves as a lobby and lounge for the AMC Empire 25.

Woods leased the site in August 1911, and the Eltinge Theatre opened on September 11, 1912, with the play

Site

The Empire Theatre is on the south side of

The

The surrounding area is part of Manhattan's Theater District and contains many Broadway theaters.[2][10] In the first two decades of the 20th century, eleven venues for legitimate theatre were built within one block of West 42nd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues.[11][12] The New Amsterdam, Harris, Liberty, Eltinge (now Empire), and Lew Fields theaters occupied the south side of the street. The original Lyric and Apollo theaters (combined into the current Lyric Theatre), as well as the Times Square, Victory, Selwyn (now Todd Haimes), and Victoria theaters, occupied the north side.[12] These venues were mostly converted to movie theaters by the 1930s, and many of them had been relegated to showing pornography by the 1970s.[12][13]

Design

The Empire Theatre, originally the Eltinge 42nd Street Theatre, was designed by

Facade

The square facade of the Empire Theatre is made of terracotta and has little ornamentation compared with other theaters built around the same time. The center of the facade contains a three-story arch, which originally illuminated the rear of the auditorium.[22] The arch was intended to resemble a Roman triumphal arch.[23] It is surrounded by an ornately carved frame.[24] The outermost sections of the facade are slightly projecting piers, which flank the arch.[24][25] According to Christopher Gray of The New York Times, the facade was typical of Lamb's 1910s theater designs, which "emphasized broad swaths of cream- or white-colored glazed terra cotta with a bit of polychromy and deep dramatic piers, window recesses and other large elements".[25]

In the original design, there were four pairs of doors at ground level, underneath a steel-and-glass marquee that protruded onto the sidewalk.[26][3] Both the entrance and the stage door were on 42nd Street, in contrast to other theaters along the same block (including the New Amsterdam and Harris), which had their stage doors on 41st Street.[27] On either side of the main entrance, the lowest section of the ground-level facade contained a granite water table, above which were doorways set within a rusticated stone facade.[24] The original water table was removed when the theater was relocated in 1998.[28][16] The second and third floors are mostly devoid of ornamentation. The center of the arch is topped by a cartouche, and the outer piers also contain cartouches at the third story. A carved cornice runs above the third story.[24]

The fourth story contains six recessed rectangular windows, which overlooked the offices of the theater's manager

Interior

The superstructure of the theater is composed of a steel frame with brick walls measuring 18 inches (460 mm) thick.[28][31] The Eltinge Theatre could not contain interior columns because they would obstruct audience members' sightlines, so the side walls and the ceiling were designed to be stronger and more rigid than in a conventional building.[28] Above the auditorium was Woods's office, which had green carpets and walnut-paneled walls.[32]

Original design

The theater had 750 seats on three levels.[4][5] These were proportioned in "slender", "medium", and "stout" widths for patrons of different sizes.[33] The side walls were steeply angled to give the impression that the auditorium was larger than it actually was.[23] The auditorium was decorated with ancient Egyptian and Greek details.[23][4] These included a proscenium arch decorated with sphinxes and winged disks. The proscenium was flanked by smaller arches, each of which contained two levels with two boxes each. The boxes stepped down toward the stage, and the fronts of each box were decorated with sculpted medallions, flanked by sculpted figures.[23] The boxes were removed in the 1930s when the theater was converted into a burlesque venue.[17]

The sounding board above the proscenium arch contained a mural, which depicted three robed women dancing to music[23][34] and was painted by French artist Arthur Brounet.[34] According to The New York Times, the women depicted in the mural may have been based on different outfits Eltinge wore.[34] The auditorium contains a domed ceiling.[23][34] There was originally a chandelier hanging from the center of the ceiling, but it was removed in the 1930s.[17]

Current design

When the theater building was repurposed in 1998, the steeply-raked balcony levels were replaced with mezzanines that contained restaurants.[17][35] Escalators pass through the former proscenium arch to the newer multiplex screens above.[8] There are three levels of lobbies, which lead to the screening rooms.[34] The former auditorium comprises the first two stories, while the concession stand is on the third story.[36] The movie screens are spread across five stories,[4][37] connected by 14 escalators. The multiplex contains an additional six mezzanines, which are connected by elevators.[4] In addition to the proscenium arch, other decorative details remain intact within the multiplex's lobby.[30] A portion of the AMC multiplex is located on a truss above the original Empire Theatre building, which measures 20 feet (6.1 m) deep and is placed 60 feet (18 m) above ground level.[38]

The screening rooms originally had 4,916 seats in total,[21][39] although this had been reduced to 4,764 seats by 2011.[30] Each of the 25 rooms contains a curved screen spanning the width of the room. The rooms contain stadium seating, with each row being 18 inches (460 mm) higher than the one in front of it.[17] The rooms each contain up to 600 seats.[34][40] On the sixth story are seven smaller screens,[21] which are used for independent, foreign-language, and art films.[34][21] Two of the screening rooms include leather seats, which were intended for large gatherings such as business presentations and private parties. In addition, there is a private 60-seat screening room that can be rented out for events.[4] In total, the multiplex had 34 plasma screens and seven projectors when it opened; some of the screens were located within the lobby.[35] When the theater opened, all of its screening rooms contained digital audio systems.[40][41]

History

Legitimate shows

1910s

In August 1911, Woods announced that he had signed a 21-year lease for an 80-by-100-foot (24 by 30 m) plot just west of the Liberty Theatre. Woods planned to build a 1,000-seat theater named in honor of Julian Eltinge.[49][50] It would be the eighth theater to be constructed on 42nd Street, after the New Amsterdam, Liberty, Harris, American, Lyric, Republic, and Victoria theaters.[51] The George A. Just Company received the contract for the theater's structural steel, while the Fleischmann Brothers received the general construction contract.[52] By January 1912, Variety magazine reported that the Eltinge Theatre was nearly completed and was ready to open that April.[53] Woods moved his executive offices from the Putnam Building to the entire upper floor in August 1912.[54][55]

The Eltinge Theatre opened on September 11, 1912, with Bayard Veiller's melodrama Within the Law.[56][57] The drama had previously been successful in Chicago,[58] and it ran at the Eltinge for 541 performances through the end of 1913.[59][60] Many of the Eltinge's early productions were similarly successful.[59][61] The next hit at the Eltinge was the play The Yellow Ticket,[61][62] featuring Florence Reed and John Barrymore, which opened in January 1914[63] and ran for 183 performances.[64][65] Later the same year, Edward Sheldon's play The Song of Songs opened at the Eltinge,[66] running for six months.[67] The theater also hosted Fair and Warmer, which opened in December 1915[68][69] and transferred to the Harris Theatre after seven months.[65] The Max Marcin play Cheating Cheaters opened at the Eltinge in August 1916,[70] with 286 performances over the next several months.[71][72] Within five years of its opening, the Eltinge Theatre was known as a "lucky house", in part because Woods often booked or produced popular comedies and melodramas.[73]

The Eltinge screened films in early 1917, such as the documentary Birth[74] and the educational movie Trip Through China.[75] The same year, the Eltinge's stage was enlarged in advance of the 1917–1918 theatrical season.[76] The theater's next hit was Business Before Pleasure, starring Barney Bernard and Alexander Carr,[73] which ran from August 1917 to June 1918.[77] This was followed by the play Under Orders, which opened in September 1918;[78][79] it ran for several months despite having only two performers, in contrast to many contemporary productions that enjoyed large casts.[73] The Eltinge also hosted Wilson Collison's Up in Mabel's Room, which opened in January 1919,[80][81] and Collison and Avery Hopwood's The Girl in the Limousine, which opened the same October.[82][83]

1920s

The Eltinge did not host many long-lasting productions during the 1920s, likely because of the growing popularity of larger theaters and because Woods was busy producing other shows.[73] With only 829 seats in 1919, the Eltinge was smaller than most of the area's other theaters.[84] The play Ladies' Night, which opened in 1920, was the theater's first hit of that decade, running for nearly a year.[73][85] In July 1921, Samuel Augenblick and Louis B. Brodsky bought the Liberty and Eltinge theaters from the heirs of Charlotte M. Goodridge, although this had no effect on Woods's lease.[86][87] Later the same year, the theater hosted The Demi-Virgin, which transferred from the Times Square Theatre to finish its 268-performance run.[88] The Demi-Virgin was the subject of a lengthy legal dispute regarding whether it was an "indecent" show, which Woods ultimately won.[89] After The Demi-Virgin closed, most of the Eltinge's productions ran for fewer than 200 performances,[90] including East of Suez in 1922[91][92] and The Woman on the Jury in 1923.[93][94] One of the exceptions was Archibald and Edgar Selwyn's comedy Spring Cleaning, which opened in November 1923[90][95] and ran for seven months.[96]

The firm of Mandelbaum & Lewine, along with Max N. Natanson, bought the Liberty and Eltinge theaters in November 1923

Woods leased the Eltinge in March 1927 to Lester Bryant, who was sponsored by a group of wealthy men.[109][110] By then, Woods was producing multiple large shows, which the theater's small capacity could not accommodate.[110] The Lambert Theatre Corporation, a venture in which Bryant was a partner,[111] leased the Eltinge during the 1927–1928 theatrical season, hosting seven shows in eight months.[32] Louis I. Isquith leased the theater during mid-1928, presenting a series of plays with low ticket prices.[112][113] Woods subsequently took back the theater's lease and produced the revue Blackbirds of 1928,[32] which transferred from the Liberty and ran until June 1929.[114] Following the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Woods produced several plays, which all had short runs.[32] The play Murder on the Second Floor, featuring Laurence Olivier, opened in late 1929.[115][116] This was followed the next year by Love Honor and Betray with Clark Gable;[117][118] the Theatre Guild's production of A Month in the Country;[119] and the play The Ninth Guest.[120][121] The theater's last-ever legitimate show was First Night, produced by Richard G. Herndon, which closed in February 1931.[32] By then, there were rumors that the Eltinge could be converted to a movie theater or burlesque house.[122]

Burlesque

Woods subleased the Eltinge Theatre to Max Rudnick in February 1931. (Woods continued to occupy the fourth-floor offices, as his lease did not expire for another two years.) Rudnick converted the Eltinge into a stock burlesque theater,[123] and launched his first burlesque shows there on March 6.[124][125] The Eltinge was the second theater on 42nd Street to feature stock burlesque, following Minsky's Republic Theater (now the New Victory) which opened a month earlier.[126][127] The Eltinge's conversion to burlesque was due in part to the Depression and in part to a general decline in the Broadway theater industry in the mid-20th century; from 1931 to 1950, the number of legitimate theaters decreased from 68 to 30.[128][129]

The Eltinge and the Republic were financially successful by mid-1931,[127] but local business owners opposed burlesque, claiming that the shows encouraged loitering, crime and decreased property values.[130][131] In New York, theater licenses were subject to yearly renewal,[132] and opponents of burlesque tried to have the licenses revoked.[126][133] The nearby Republic and other theaters had been raided by police, but these actions only boosted the theaters' popularity.[134] The Eltinge's operating license was temporarily revoked in September 1932,[135][136] only to reopen the next month.[137][138] The Eltinge toned down its shows whenever it was raided, but reverted to form soon after.[139] By 1933, Rudnick had taken over the theater building, and Woods relocated his office to the New Amsterdam.[32]

After he was elected mayor in 1934, Fiorello La Guardia began a crackdown on burlesque and appointed Paul Moss as license commissioner.[126][140] Rudnick, his assistant manager, and several performers were arrested on indecency charges in November 1934,[141] but were ultimately exonerated.[142] The Eltinge continued to operate as a burlesque house for several more years.[143] However, after a series of sex crimes in early 1937,[140] the La Guardia administration ordered all burlesque houses to remove the word "burlesque" from their marquees that June.[144] The Eltinge continued to host burlesque performances, which were billed as variety shows.[145][146] The theater operated without a permit for several weeks in late 1937 before its license was renewed at the end of that year.[147] Even without burlesque on its marquee, the Eltinge remained popular,[148] although it was only one of three remaining burlesque theaters in the city by 1940.[149] Moss again refused to renew the Eltinge's operating license in early 1942,[150][151] marking the permanent end of burlesque at the Eltinge.[139]

Movie theater and decline

After the Eltinge's burlesque license expired, J. J. Mage leased the theater from the Brandts.[152][153] Mage reopened the Eltinge as the Laff-Movie in July 1942,[152] with 759 seats.[39] The new name reflected the fact that it showed only comedic shorts and feature films.[152][154] The Brandt family took over the Laff-Movie, along with the neighboring Liberty Theatre, in December 1944.[155] By the mid-1940s, the ten theaters along 42nd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues were all showing movies; this led Variety to call the block the "biggest movie center of the world".[153] The Brandt family operated seven of these theaters, while the Cinema circuit operated the other three.[153][155] The Brandt theaters included the Selwyn, Apollo, Times Square, Lyric, and Victory theaters on the north side of 42nd Street,[156][157] as well as the Laff-Movie and the Liberty Theatre on the south side.[155] Several producers offered to stage legitimate productions in the Brandt theaters, but none of the offers were successful.[158]

William Brandt said in 1953 that any of his 42nd Street theaters could be converted into a legitimate house within 24 hours' notice, but producers did not take up his offer.[159] Brandt announced in August 1953 that he would renovate the Laff-Movie, showing feature films exclusively.[160] The theater was renamed the Empire in 1954;[4][61][139] the name had previously been used by a theater on 41st Street that had just been demolished.[5][39] By the late 1950s, the Empire was classified as a "reissue house", displaying reruns of films and changing its offerings twice a week. Tickets cost 25 to 65 cents apiece, the cheapest admission scale for any theater on 42nd Street. The Empire and the other 42nd Street theaters operated from 8 a.m. to 3 a.m., with three shifts of workers. The ten theaters on the block attracted about five million visitors a year between them.[161]

The 42nd Street Company was established in 1961 to operate the Brandts' seven theaters on 42nd Street.[162][163] By the early 1960s, the surrounding block had decayed, but many of the old theater buildings from the block's heyday remained, including the Empire.[164] Martin Levine and Richard Brandt took over the 42nd Street Company in 1972.[162][163] At the time, the Empire was presenting "showcase films".[165] The other six theaters showed a variety of genres, though Levine said none of the company's 42nd Street theaters showed hardcore porn. The Brandts' theaters had a combined annual gross of about $2 million and operated nearly the entire day.[165] However, the area was in decline; the Brandts' theaters only had three million visitors in 1977, about half of the number in 1963.[166] The Brandts' movie theaters on 42nd Street continued to operate through the mid-1980s, at which point the Empire was showing kung-fu and horror films.[167]

Restoration

Preservation attempts

The 42nd Street Development Corporation had been formed in 1976 to discuss plans for redeveloping Times Square.

The LPC started to consider protecting theaters, including the Empire Theatre,[179] with discussions continuing over the next several years.[180] While the LPC granted landmark status to many Broadway theaters starting in 1987, it deferred decisions on the exterior and interior of the Empire Theatre.[181] Further discussion of the landmark designations was delayed for several decades.[182] In late 2015, the LPC hosted public hearings on whether to designate the Empire and six other theaters as landmarks.[183] The LPC rejected the designations in February 2016 because the theaters were already subject to historic-preservation regulations set by the state government.[184]

Initial plans

The

The New York Mart plan consisted of a garment merchandise mart on Eighth Avenue between 40th and 42nd Streets, opposite Port Authority Bus Terminal.[193][194] The project was to be completed by the Times Square Redevelopment Corporation, comprising members of the New York state and city governments.[195] Under this plan, the Empire and Liberty theaters would be renovated, although the extent of the renovations was unclear.[195][196] David Morse and Richard Reinis were selected in April 1982 to develop the mart,[194][195] but they were removed from the project that November due to funding issues.[195][197] Subsequently, the state and city disputed over the replacement development team, leading the city to withdraw from the partnership in August 1983.[198][186] The state and city reached a compromise on the development team that October, wherein the mart would be developed by Tishman Speyer, operated by Trammell Crow, and funded by Equitable Life Assurance.[186][199]

The Brandts leased all their movie theaters on 42nd Street, including the Empire, to the Cine 42nd Street Corporation in 1986.[200] Cine 42nd Street subleased the theater to Sweetheart Theatres Inc., which screened pornographic movies.[139] The Empire Theatre was still part of the mart project in 1987.[201][202] Though the theater was tentatively slated to be used for fashion shows and other events,[202] the city and state governments had not reached an agreement with private developers regarding the mart.[201] The merchandise mart was ultimately never built; the northern part of the site became 11 Times Square, while the southern part became the New York Times Building.[186]

In 1989,

Relocation and restoration

By 1995, real-estate development firm

Engineers were preparing to raze several buildings along the south side of 42nd Street by mid-1997,[219] including the Lew Fields Theatre, whose site would be occupied by the relocated Empire.[6] The rear of the theater was braced because workers had to remove the stage and the fly systems, and the removal would undermine the building's structural integrity.[219] Workers installed piles on the adjacent lots to the west, which had previously contained residences with basements.[47] The basements were demolished,[28] allowing the theater building to rest directly on Manhattan's bedrock instead of atop an unstable layer of dirt.[47] There were 430 piles in total,[16] which supported a set of eight parallel tracks.[16][4][215] Workers also poured 70 concrete caps inside the theater building.[16] After the tracks had been installed, workers placed a dolly of steel beams above the tracks, which in turn traveled above a series of 250 rollers.[215] The perimeter of the dolly contained load-bearing beams that supported the weight of the theater.[16] The lowest portions of the walls were removed, detaching the theater from the original foundations. The theater was then lifted about 1⁄8 inch (3.2 mm) so it could be hoisted onto the dolly.[28][16] Workers used hydraulic jacks to lift the theater.[47][215]

The theater's relocation required several months of preparation.[16][220] The entire relocation was supposed to have occurred on February 17, 1998, but this was postponed because New York City officials wanted to perform the relocation on a weekend.[47] As such, the structure was initially moved 30 feet (9.1 m) on February 22,[16][5] while the rest of the relocation occurred during a five-hour period on March 1.[16][215][221] Hydraulic jacks moved the theater in five-minute bursts, moving the theater about 5 feet (1.5 m) during each burst.[47] Two large balloons representing Abbott and Costello, who first performed together at the theater in 1935, were rigged to appear as if they were dragging the theater westward.[5][221][222] Large construction markers, referencing Abbott and Costello's "Who's on First?" comedy routine, were placed along the construction fence to mark the move's progress.[222] Two portable heaters continued to heat the empty auditorium as it was being relocated.[4][28] The event attracted several hundred spectators.[222] Until 2022,[b] the 3,700-short-ton (3,300-long-ton; 3,400 t) structure was the heaviest building in New York City to have been relocated.[16][19]

After the theater was relocated, Forest City Ratner planned to recreate stonework on the facade, which at several places had been stripped to a layer of brick.[28] At the time of the relocation, its interior was in poor condition, with peeling paint and missing boxes, but the auditorium retained most of its plasterwork.[28][139] The theater's facade was cleaned, while the interior was adapted to become the lobby of the AMC multiplex.[8] Midway through the project, Forest City Ratner decided to add a 455-room hotel above the new entertainment and retail spaces to the east. The hotel was built atop a large truss, which in turn was supported by reinforced-concrete walls and eight large steel columns, since the hotel was structurally separate from the rest of the development. The large size of the steel columns required the architects to slightly reduce the size of the AMC multiplex.[224]

Multiplex

The AMC Empire 25 opened in April 2000, being the second multiplex to open on the block, after the E-Walk complex.[18][225] Theatrical insiders claimed that the Empire 25 had cost $70 million, which might have made it the most expensive movie theater ever built, but AMC refused to disclose the construction cost.[226] In its first year of operation, the Empire 25 struggled to compete with the E-Walk;[226] it had not screened many major films in part because of a lack of successful feature films.[225] By 2001, the Empire 25 had become one of the most popular in the world, grossing over $500,000 a week.[226] The Times Square Cafe opened on the multiplex's balcony level in 2001[227] and later closed.[39] The Hollywood Reporter, in 2005, quoted a Focus Features executive as saying that the Empire 25 was "one of the best art houses in the country".[228] A digital IMAX screen, the first in New York City, opened at the Empire 25 in September 2008.[39]

The multiplex remained one of the United States' most profitable movie theaters in the mid-2000s.[229] It was especially popular on holiday weekends; for instance, it hosted 131 screenings of 14 separate films on Christmas Day in 2009.[230] The Hollywood Reporter reported in 2011 that the Empire 25 had two million guests per year or an average of 40,000 guests per week. By contrast, the average multiplex in the United States had a third as many visitors.[231] The Empire 25's success was attributed not only to its central location near Times Square but also because it offered independent and art films in addition to major features.[33] Because of varying patronage throughout the week, the number of employees varied widely, from 20 workers on a typical weekday to nearly 140 during the summer.[36] AMC also rented out the Empire 25's space for various events, such as a showcase of 3D films[232] and an experimental-music festival.[233]

The Empire 25, along with other movie theaters in New York state, was temporarily closed during much of 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[234] The theater reopened in March 2021 after being dark for nearly a year.[235][236] The Empire 25 remains AMC's flagship multiplex in the 2020s.[237]

Notable productions

Productions are listed by the year of their first performance. This list only includes Broadway shows; it does not include burlesque shows or films.[46][238]

- 1912: Within the Law[60][56]

- 1914: The Yellow Ticket[64][62]

- 1914: The Song of Songs[67]

- 1915: See My Lawyer[239]

- 1915: Fair and Warmer[68][69]

- 1916: Cheating Cheaters[71][72]

- 1919: Up in Mabel's Room[80][81]

- 1919: The Girl in the Limousine[82][83]

- 1920: Ladies' Night[85][73]

- 1921: Back Pay[240]

- 1921: The Demi-Virgin[73][88]

- 1921: Blood and Sand[241][242]

- 1922: East of Suez[91][92]

- 1923: The Woman on the Jury[93][94]

- 1923: Spring Cleaning[96][243]

- 1925: The Fall Guy[244]

- 1926: The Ghost Train[106]

- 1927: The Love Thief[245]

- 1929: Murder on the Second Floor[115][116]

- 1930: A Month in the Country[119]

- 1930: The Ninth Guest[120][121]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ The sites were:[188]

- Northwest corner of 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue: now 3 Times Square

- Northeast corner of 42nd Street and Broadway: now 4 Times Square

- Southwest corner of 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue: now 5 Times Square

- South side of 42nd Street between Seventh Avenue and Broadway: now 7 Times Square (Times Square Tower)

- ^ The Palace Theatre, which weighed 7,000 short tons (6,200 long tons; 6,400 t), was raised by about 30 feet (9.1 m) from January to April 2022.[223]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e "234 West 42 Street, 10036". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b Morrison 1999, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fuchs 2000, p. 218.

- ^ a b c d e Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 712.

- ^ a b Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 139.

- New 42nd Street. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 7, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Times Sq-42 St (S)". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ New York City, Proposed Times Square Hotel UDAG: Environmental Impact Statement (Report). United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1981. p. 4.15. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ProQuest 1505606157.

- ^ a b c Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 675.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ISSN 0042-2738.

- ^ a b Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 143.

- ^ ProQuest 235695132.

- ^ from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ProQuest 219191443.

- ^ ProQuest 227783089.

- from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Fuchs 2000, p. 216.

- ^ Henderson & Greene 2008, pp. 143, 147.

- ^ a b c d e f g Morrison 1999, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d Morrison 1999, p. 78.

- ^ from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ a b Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 147.

- ProQuest 1113135958.

- ^ from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d McClintock 2011, p. 62.

- ^ ProQuest 211007920.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 153.

- ^ a b McClintock 2011, p. 61.

- ^ from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Fuchs 2000, p. 220.

- ^ a b McClintock 2011, p. 63.

- ^ McClintock 2011, p. 60.

- ProQuest 227883027.

- ^ a b c d e Melnick, Ross. "AMC Empire 25". Cinema Treasures. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ ProQuest 209650618.

- ProQuest 1286225873.

- ^ Swift, Christopher (2018). "The City Performs: An Architectural History of NYC Theater". New York City College of Technology, City University of New York. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Theater District –". New York Preservation Archive Project. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 2.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 4.

- ^ a b "Empire Theatre-IBDB: The Internet Broadway Database". ibdb.com. The Broadway League. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-415-93853-2. Archivedfrom the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ProQuest 1031424825.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ "Contracts Awarded". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 88, no. 2274. October 14, 1911. p. 558. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ProQuest 1528966460.

- ISSN 0042-2738. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ProQuest 1031433159.

- ^ from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ProQuest 574992515.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Henderson & Greene 2008, pp. 147–148.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (September 11, 1912). "Within the Law – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "Within the Law (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1912)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c Bloom 2007, p. 67.

- ^ a b Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 148.

- ProQuest 575213090.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (January 20, 1914). "The Yellow Ticket – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "The Yellow Ticket (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1914)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 150.

- from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (December 22, 1914). "The Song of Songs – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "The Song of Songs (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1914)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (November 6, 1915). "Fair and Warmer – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "Fair and Warmer (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1915)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (August 9, 1916). "Cheating Cheaters – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "Cheating Cheaters (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1916)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on March 9, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Henderson & Greene 2008, pp. 150–151.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 151.

- ProQuest 575719466.

- ProQuest 1529024878.

- ProQuest 1031539124.

- ^ The Broadway League (August 15, 1917). "Business Before Pleasure – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 3, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022."Business Before Pleasure (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1917)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ProQuest 1031562315.

- ^ The Broadway League (August 20, 1918). "Under Orders – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022."Under Orders (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1918)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (January 15, 1919). "Up in Mabel's Room – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "Up in Mabel's Room (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1919)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (October 6, 1919). "The Girl in the Limousine – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 26, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "The Girl in the Limousine (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1919)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ProQuest 1505624845.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (August 9, 1920). "Ladies' Night – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "Ladies' Night (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1920)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ProQuest 576438379.

- from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (October 18, 1921). "The Demi-Virgin – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved April 12, 2022."The Demi-Virgin (Broadway, Times Square Theatre, 1921)". Playbill. Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ a b Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 152.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (September 21, 1922). "East of Suez – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "East of Suez (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1922)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (August 15, 1923). "The Woman on the Jury – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "The Woman on the Jury (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1923)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (November 9, 1923). "Spring Cleaning – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "Spring Cleaning (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1923)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on June 18, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ProQuest 1237308941.

- ProQuest 103149218.

- ProQuest 1505527262.

- ^ a b Henderson & Greene 2008, pp. 152–153.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ProQuest 1031769207.

- ^ ProQuest 1031778513.

- ^ The Broadway League (October 7, 1925). "Stolen Fruit – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on June 17, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022."Stolen Fruit (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1925)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (August 25, 1926). "The Ghost Train – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "The Ghost Train (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1926)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (February 22, 1927). "Crime – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on April 16, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022."Crime (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1927)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ProQuest 1031823687.

- ^ ProQuest 1130545593.

- ProQuest 1528986282.

- from the original on March 14, 2018. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ProQuest 1113364604.

- from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (September 11, 1929). "Murder on the Second Floor – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "Murder on the Second Floor (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1929)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (March 12, 1930). "Love, Honor and Betray – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022."Love, Honor and Betray (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1930)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (March 17, 1930). "A Month in the Country – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "A Month in the Country (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1930)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (August 25, 1930). "The Ninth Guest – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "The Ninth Guest (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1930)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ProQuest 1114070490.

- ProQuest 99448316.

- ^ a b c Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 27.

- ^ from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ProQuest 1505767801.

- ProQuest 1291337111.

- from the original on June 13, 2022. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ProQuest 1221273082.

- ProQuest 224261269.

- from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ^ Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 73.

- from the original on March 14, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ProQuest 1114532418.

- from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ProQuest 1114537540.

- ^ a b c d e Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 154.

- ^ from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 74.

- ProQuest 1248506377.

- ProQuest 1032132714.

- from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ProQuest 1243091655.

- ProQuest 1256851037.

- ProQuest 1284469087.

- from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 2297928054.

- ^ ProQuest 1285899443.

- from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ProQuest 106913088.

- ProQuest 1283104921.

- from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ProQuest 2338378743.

- ProQuest 1014785728.

- ^ ProQuest 1476041465.

- ^ ProQuest 1014665133.

- ProQuest 1325840251.

- ^ ProQuest 963281987.

- from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved April 10, 2022.

- ProQuest 1438444052.

- ProQuest 511943242.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 679.

- from the original on January 17, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 681.

- from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 691.

- from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- from the original on September 21, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Rajamani, Maya (February 23, 2016). "7 Theaters Among Midtown and Hell's Kitchen Sites Up for Landmarking". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Bindelglass, Evan (November 9, 2015). "42nd Street Theaters, Osborne Interior, More Round Out First Manhattan Landmarks Backlog Hearing". New York YIMBY. Archived from the original on September 30, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "7 Theaters on 42nd Street Fail to Make Cut for Landmark Consideration". DNAinfo New York. February 23, 2016. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 683.

- ^ Stephens, Suzanne (March 2000). "Four Times Square" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 188. p. 92. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 29, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved April 10, 2022.

- ProQuest 1438352463.

- from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ProQuest 1445519202.

- ^ from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 682.

- from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 205.

- ^ from the original on November 1, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 962838257.

- from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 962907555.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 693.

- from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ProQuest 1286158079.

- from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved April 10, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved April 10, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1286158079.

- ^ "42nd Street: No beat of dancing feet- yet" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 177. June 1989. p. 85. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "42nd Street Project Advances with Move of Historic Theater" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 186, no. 4. April 1998. p. 38. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on September 23, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ from the original on September 18, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved September 23, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ProQuest 408348740.

- from the original on September 23, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 236260490. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ProQuest 235327615.

- ProQuest 200338285.

- ProQuest 306282850.

- ^ McClintock 2011, pp. 60–61.

- ProQuest 811315089.

- from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Goldsmith, Jill (March 6, 2021). "New York City Cinemas Reopen Today After A Year; What To Expect As Tickets On Sale From 'Raya' To 'Tenet'- Update". Deadline. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "New York cinemas reopen after a year on pause – but will film fans return?". the Guardian. March 6, 2021. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Eltinge 42nd Street Theatre (1912) New York, NY". Playbill. December 12, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ The Broadway League (September 2, 1915). "See My Lawyer – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "See My Lawyer (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1915)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (August 30, 1921). "Back Pay – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "Back Pay (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1921)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (September 20, 1921). "Blood and Sand – Broadway Show – Play". IBDB. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

"Blood and Sand (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1921)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2024. - ISBN 9780786453092.

- ProQuest 1665846582.

- ^ The Broadway League (March 10, 1925). "The Fall Guy – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "The Fall Guy (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1925)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on June 15, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (January 24, 1927). "The Love Thief – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2022; "The Love Thief (Broadway, Empire Theatre, 1927)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

Sources

- Bloom, Ken (2007). The Routledge Guide to Broadway (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97380-9.

- Cort Theater (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 17, 1987.

- Fuchs, Andreas (March 1, 2000). "Rebuilding the Empire". Film Journal International. Vol. 103, no. 3. pp. 216, 218, 220. ProQuest 1286216544.

- Henderson, Mary C.; Greene, Alexis (2008). The Story of 42nd Street: The Theatres, Shows, Characters, and Scandals of the World's Most Notorious Street. New York: Back Stage Books. OCLC 190860159.

- McClintock, Pamela (May 6, 2011). "The Busiest Movie Theatre in America". The Hollywood Reporter. Vol. 417. pp. 60–63. ProQuest 865330895.

- Morrison, William (1999). Broadway Theatres: History and Architecture. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-40244-4.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2006). New York 2000: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Bicentennial and the Millennium. New York: Monacelli Press. OL 22741487M.