Emydidae

| Emydidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Black-knobbed map turtle | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae (Rafinesque, 1815)[2] |

| Subfamilies and genera | |

| Synonyms [2] | |

| |

Emydidae (

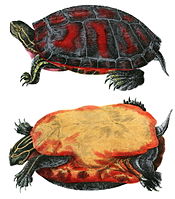

Description

The upper shell (

The limbs of these turtles are adapted for swimming, with every member having some level of toe webbing.[1]

Most species exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination, as is typical of turtles; however, one species (the wood turtle) is known to have genetic sex determination.[5]

Behavior

Food habits range from strictly

Knowledge of reproductive behavior ranges from some of the most detailed, long-term study of any taxon (Chrysemys picta in Michigan) to a total lack of information. In many species, dimorphisms include elongated foreclaws or a concave plastron in the male. The longer claws are used in a courtship routine in which the male faces the female and fans her face. The concave plastron allows the male to mount females in species with more domed carapaces (e.g., Terrapene). Reproduction is on an annual cycle, and multiple clutches may be produced in a single season. Clutch size is quite variable, ranging from as few as two to more than 30 eggs.

Threats

Emydids are the turtles most commonly sold through the pet trade. The pond slider (Trachemys scripta) has expanded its range through the careless release of pets into the wild. Many Asian species are threatened by over-collection of animals for sale in markets and into the pet trade. The North American species Clemmys muhlenbergii is listed as an Appendix II species by CITES and is considered threatened or endangered in many states. This status is the result of habitat degradation and over-collection.

Systematics and evolution

The Emydidae are most closely related to the

The enigmatic big-headed turtle (Platysternon megacephalum) was for some time considered a specialized, but still very primitive early offshoot of the Emydidae. With the Geoemydidae being split off, though, it is better reinstated as its own family, the Platysternidae, though it seems very close to the emydid-geoemydid group.

Fossil record

Presumed emydids are well represented in the

Classification

The two subfamilies and genera are arranged as follows:[3]

- Subfamily Emydinae

- Clemmys

- Emys

- Actinemys

- Emydoidea

- Glyptemys

- Terrapene

- † Wilburemys

- Subfamily Deirochelyinae

- Chrysemys

- Deirochelys

- Graptemys

- Malaclemys

- Pseudemys

- Trachemys

- Subfamily incertae sedis

- †Acherontemys

- †Acherontemys heckmani[7]

- †

- †Psilosemys

- †Acherontemys

References

- ^ a b c d Ernst 1994, p. 203

- ^ a b Rhodin 2010, p. 000.99

- ^ a b Rhodin 2010, pp. 000.99–000.107

- ^ EMYSystem Family Page: Emydidae (Pond Turtles)

- S2CID 14434440.

- ^ James E. Martin; V. Standish Mallory (2011). "Vertebrate paleontology of the late Miocene (Hemphillian) Wilbur Locality of central Washington". Paludicola. 8 (3): 155–185.

- S2CID 214641639.

- ISBN 978-94-007-4308-3.

- Bibliography

- Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger William; Lovich, Jeffery E. (1994). Dutro, Nancy P. (ed.). Turtles of the United States and Canada. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 203–204. ISBN 1-56098-346-9.

- Rhodin, Anders G.J.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Iverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (2010-12-14). "Turtles of the World 2010 Update: Annotated Checklist of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution and Conservation Status" (PDF). pp. 000.89–000.138. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2010-12-15.

External links