English folk music

| Culture of England |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

|

|

Folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

|

Art |

| Literature |

|

|

The folk music of England is a tradition-based music which has existed since the later

There are distinct regional and local variations in content and style, particularly in areas more removed from the most prominent English cities, as in Northumbria, or the West Country. Cultural interchange and processes of migration mean that English folk music, although in many ways distinctive, has significant crossovers with the music of Scotland. When English communities migrated to the United States, Canada and Australia, they brought their folk traditions with them, and many of the songs were preserved by immigrant communities.

English folk music has produced or contributed to several cultural phenomena, including

History

Origins

In the strictest sense, English folk music has existed since the arrival of the

16th century to the 18th century

While there was distinct court music, members of the social elite into the 16th century also seem to have enjoyed, and even to have contributed to the music of the people, as

In the 16th century the changes in the wealth and culture of the upper social orders caused tastes in music to diverge.

Problems playing this file? See media help.

By the mid-17th century, the music of the lower social orders was sufficiently alien to the aristocracy and "middling sort" for a process of rediscovery to be needed in order to understand it, along with other aspects of popular culture such as festivals, folklore and dance.

It was in this period, too, that English folk music traveled across the Atlantic Ocean and became one of the foundations of American traditional music. In the colonies, it mixed with styles of music brought by other immigrant groups to create a host of new genres. For instance, English ballads, along with Irish, Scottish, and German musical traditions when combined with the African banjo, Afro-American rhythmic traditions and the Afro-American jazz and blues aesthetic led in part to the development of bluegrass and country music

Early 19th century

With the

Technological change made new instruments available and led to the development of silver and

Folk revivals 1890–1969

From the late 19th century there were a series of movements that attempted to collect, record, preserve and later to perform, English folk music and dance. These are usually separated into two folk revivals.

The first, in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, involved figures including collectors

There are various databases and collections of English folk songs collected during the first and second folk revivals, such as the Roud Folk Song Index, which contains references to 25,000 English language folk songs, and the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, a multimedia archive of folk-related resources.[30] The British Library Sound Archive contains thousands of recordings of traditional English folk music, including 340 wax cylinder recordings made by Percy Grainger in the early 1900s.[31]

Progressive folk

There was a brief flowering of English progressive folk in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with groups like the

British folk rock

British folk rock developed in Britain during the mid to late 1960s by the bands

Folk punk

In the mid-1980s a new rebirth of English folk began, this time fusing folk with energy and political aggression derived from punk rock. Leaders included

Folk metal

In a process strikingly similar to the origins of British folk rock in the 1960s, the English thrash metal band Skyclad added violins from a session musician on several tracks for their 1990 debut album The Wayward Sons of Mother Earth.[45] When this was well received they adopted a full-time fiddle player and moved towards a signature folk and jig style leading them to be credited as the pioneers of folk metal, which has spread to Ireland, the Baltic and Germany.[45]

Traditional folk resurgence 1990–present

The peak of traditional English folk, like progressive and electric folk, was the mid- to late-1970s, when, for a time it threatened to break through into the mainstream. By the end of the decade, however, it was in decline.[46] The attendance at, and numbers of folk clubs began to decrease, probably as new musical and social trends, including punk rock, new wave and electronic music began to dominate.[47] Although many acts like Martin Carthy and the Watersons continued to perform successfully, there were very few significant new acts pursuing traditional forms in the 1980s. This began to change with a new generation in the 1990s. The arrival and sometimes mainstream success of acts like Kate Rusby, Bellowhead, Nancy Kerr, Kathryn Tickell, Jim Moray, Spiers and Boden, Seth Lakeman, Frank Turner, Laura Marling and Eliza Carthy, all largely concerned with acoustic performance of traditional material, marked a radical turn around in the fortunes of the tradition.[22] This was reflected in the adoption creation of the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards in 2000, which gave the music a much needed status and focus and the profile of folk music is as high in England today as it has been for over thirty years.[48]

Folk clubs

Although there were a handful of clubs that allowed space for the performance of traditional folk music by the early 1950s, its major boost came from the short-lived British

Folk music and the radio

The difficulty of gaining regular appearances on television in England has long meant that radio has remained the major popular medium for increasing awareness of the genre. The EFDSS sponsored the

Folk festivals

Folk festivals began to be organised by the EFDSS from about 1950, usually as local or regional event with an emphasis on dance, like the

Forms of folk music

Ballads

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative story and set to music. Many ballads were written and sold as single sheet

Carols

A carol is a festive song. In modern times, carols are associated primarily with Christmas, but in reality there are carols celebrating all festivals and seasons of the year, and not necessarily Christian festivals. They were derived from a form of

Children's songs

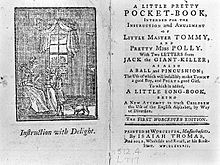

The earliest vernacular children's songs in Europe are

Erotic folk songs

It has been noted by most recent commentators on English folk song even if it was a bit immoral, that love, the erotic and even the pornographic, were major traditional themes and, if more than ballads are considered, may have been the largest groups of printed songs.

Hornpipes

The hornpipe is a style of dance music thought to have taken its name from an English reed instrument by at least the 17th century.

Jigs

Jigs are a style of dance music developed in England to accompany a lively dance with steps, turns and leaps. The term jig was derived from the French 'giguer', meaning 'to jump'.[10] It was known as a dance in the 16th century, often in 2/4 time and the term was used for a dancing entertainment in 16th century plays.[79] The dance began to be associated with music particularly in 6/8 time, and with slip jigs 9/8 time.[78] In the 17th century the dance was adopted in Ireland and Scotland, where they were widely adapted, and with which countries they are now most often associated.[80] In some, usually more northern, parts of England, these dances would be referred to as a "Gallop" – such as the Winster Gallop from Derbyshire (though this owes its origins to the Winster Morris).

Morris dance

A morris dance is a type of English folk dance, usually accompanied by music, and based on rhythmic stepping and the execution of choreographed figures by a group of dancers, often using implements such as sticks, swords, and handkerchiefs. The name is thought to derive from the term 'moorish dance', for Spanish (Muslim) styles of dance and may derive from English court dances of the period.

Protest songs

Perhaps the oldest clear example of an English protest song is the rhyme 'When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?', used in the

Sea shanties

Sea shanties are a type of work song traditionally sung by sailors. Derived from the French word 'chanter', meaning 'to sing', they may date from as early as the 15th century, but most recorded examples derive from the 19th century.[96] Shanties were usually slow rhythmic songs designed to help with collective tasks on labour-intensive sailing and later steam ships. Many were call and response songs, with one voice (the shantyman) singing a lead line and the rest of the sailors giving a response together. They were derived from varied sources, including dances, folk songs, polkas, waltzes and even West African work-songs.[97] Since different songs were useful for different tasks they are traditionally divided into three main categories, short haul shanties, for tasks requiring quick pulls over a relatively short time; halyard shanties, for heavier work requiring more set-up time between pulls; and Capstan shanties, for long, repetitive tasks requiring a sustained rhythm, but not involving working the lines.[97] Famous shanties include, the 'Blow the Man Down and 'Bound for South Australia', some of which have remained in the public consciousness or been revived by popular recordings. There was some interest in sea shanties in the first revival from figures like Percy Grainger,[98] who recorded several traditional versions on phonographs.[99][100][101] In the second revival A. L. Lloyd attempted to popularise them, recording several albums of sea songs from 1965.[21]

War songs

In England songs about military and naval subjects were a major part of the output of

Work songs

Work songs include music sung while conducting a task (often to coordinate timing) or a song linked to a task or trade which might be a connected

Regional traditions

East Anglia

Like many regions of England there are few distinctive local instruments and many songs were shared with the rest of Britain and with Ireland, although the distinct dialects of the regions sometimes lent them a particular stamp and, with one of the longest coastlines of any English region, songs about the sea were also particularly important. Along with the West Country, this was one of the regions that most firmly adopted reed instruments, producing many eminent practitioners of the melodeon from the mid-19th century. Also like the West Country it is one of the few regions where there is still an active tradition of

The Midlands

Due to its lack of clear boundaries and a perceived lack of identity in its folk music, the

The North West

Although relatively neglected in the first folk revival

Northumbria

The South East

Even excluding Sussex and London,

London

Despite being the centre of both folk revivals and the British folk rock movement, the songs of

Sussex

The West Country

Cornwall

The music of

The rest of the West Country

Outside Devon and Cornwall Celtic influence on music in the

Yorkshire

See also

- English country music – term used in 1960s to 1970s to describe a genre of instrumental traditional music

- List of selected, noteworthy folk musicians and bands (with an emphasis on artists from Britain and the U.S.A.) as contained in the Guinness Who's Who of Folk Music (pub. 1993)

Notes

- ^ R. I. Page, Life in Anglo-Saxon England (London: Batsford, 1970), pp. 159–60.

- ^ C. Parrish, The Notation of Medieval Music (Maesteg: Pendragon Press, 1978).

- ^ a b J. Forrest, The History of Morris Dancing, 1458–1750 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g h B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 45–9.

- ^ D. Starkey, Henry VIII: A European Court in England (London: Collins & Brown in association with the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, 1991), p. 154.

- ^ a b c Peter Burke, Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe (London: Billing, 1978), pp. 3, 17–19 and 28.

- ^ D. C. Price, Patrons and Musicians of the English Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 5.

- ^ J. Wainwright, P. Holman, From Renaissance to Baroque: Change in Instruments and Instrumental Music in the Seventeenth Century (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005).

- ^ M. Chanan, Musica Practica: The Social Practice of Western Music from Gregorian Chant to Postmodernism (London: Verso, 1994), p. 179.

- ^ a b c J. Ling, L. Schenck and R. Schenck, A History of European Folk Music (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1997), pp. 123, 160 and 194.

- ^ "Never heard of Barbara Allen? The world's most collected ballad has been around for 450 years..." www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g G. Boyes, The Imagined Village: Culture, Ideology, and the English Folk Revival (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993), p. 214.

- ^ W. B. Sandys, Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern (London, 1833); W. Chappell, A Collection of National English Airs (London, 1838) and R. Bell, Ancient Poems, Ballads and Songs of the Peasantry of England (London, 1846).

- ^ D. Russell, Popular Music in England, 1840–1914: A Social History (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1987), pp. 160–90.

- ^ D. Kift, The Victorian Music Hall: Culture, Class, and Conflict (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 17.

- ^ W. Boosey, Fifty Years of Music (1931, Read Books, 2007), p. 161.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j M. Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 1944–2002 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), pp. 6, 8, 32, 38, 53–63, 68–70, 74–8, 97, 99, 103, 112–4 and 132.

- ^ S. Sadie and A. Latham, The Cambridge Music Guide (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 472.

- ^ "Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders – World and traditional music | British Library – Sounds". sounds.bl.uk. Archived from the original on 2020-10-18. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ a b J. Connell and C. Gibson, Sound Tracks: Popular Music, Identity, and Place (Routledge, 2003), pp. 34–6.

- ^ a b c B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 32–6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i S. Broughton, M. Ellingham, R. Trillo, O. Duane, V. Dowell, World Music: The Rough Guide (London: Rough Guides, 1999), pp. 66–8 and 79–80.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 184–9.

- required.)

- required.)

- ^ "Fred Jordan - A Shropshire Lad CD review - The Living Tradition Magazine". www.folkmusic.net. Archived from the original on 2021-09-23. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- required.)

- ^ david. "Frank Hinchliffe - In Sheffield Park". Topic Records. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ Sansom, Ian (2011-08-05). "Great dynasties of the world: The Copper Family". The Guardian. Retrieved 2021-10-05.

- ^ "Archive collections". www.vwml.org. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders - World and traditional music | British Library - Sounds". sounds.bl.uk. Archived from the original on 2021-10-29. Retrieved 2021-10-05.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 203.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 40.

- Milwaukie MI, Hal Leonard, 2003), p. 120.

- ^ P. Buckley, The Rough Guide to Rock: the definitive guide to more than 1200 artists and bands (London: Rough Guides, 2003), pp. 145, 211–12, 643–4.

- ^ "Sold on Song", BBC Radio 2, retrieved 19/02/09.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 21–5.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 84, 97 and 103–5.

- ^ J. S. Sawyers, Celtic Music: A Complete Guide (Cambridge MA: Da Capo Press, 2001), pp. 1–12.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 240–57.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 266–70.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 197–8.

- ^ S. Broughton and M. Ellingham, World Music: Latin and North America, Caribbean, India, Asia and Pacific Volume 2 of World Music: The Rough Guide (Rough Guides, 1999), p. 75.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 136.

- ^ Allmusic. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All music guide to rock: the definitive guide to rock, pop, and soul (Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), pp. 1354–5.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 94.

- ^ D. Else, J. Attwooll, C. Beech, L. Clapton, O. Berry, and F. Davenport, Great Britain (London, Lonely Planet, 2007), p. 75.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 37.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 113.

- ^ R. H. Finnegan, The Hidden Musicians: Music-Making in an English Town (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2007), pp. 57–61.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 45.

- ^ Folk and Roots, http://www.folkandroots.co.uk/Venues_North_East.html Archived 2009-05-30 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 24/02/09.

- ^ a b c B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 119.

- ^ Lifton, Sarah (1983) The Listener's Guide to Folk Music. Poole: Blandford Press; p. 9

- ^ S. Street, A Concise History of British Radio, 1922–2002 (Tiverton: Kelly Publications, 2002), p. 129.

- ^ BBC Press release http://www.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/latestnews/2012/mark-radcliffe-adds-folk-to-radio-2-roster.html, retrieved 18/10/2012.

- ^ fRoots radio, http://www.frootsmag.com/radio/ Archived 2007-12-25 at the Wayback Machine fRoots radio, retrieved 17/02/09.

- ^ a b B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 116–7.

- ^ F. Redwood and M. Woodward, The Woodworm Era, the Story of Today's Fairport Convention (Thatcham: Jeneva, 1995), p. 76.

- ^ a b Folk and Roots, "Folk and Roots - 2009 Folk Festivals - Britain". Archived from the original on 2009-02-24. Retrieved 2009-02-25., retrieved 16/02/09.

- ^ a b c J. E. Housman, British Popular Ballads (London: Ayer, 1969), pp. 15 and 29.

- ^ J. J. Walsh, Were They Wise Men Or Kings?: The Book of Christmas Questions (Westminster: John Knox Press, 2001), p. 60.

- ^ W. J. Phillips, Carols; Their Origin, Music, and Connection with Mystery-Plays (Routledge, 1921, Read Books, 2008), p. 24.

- ^ W. E. Studwell, The Christmas Carol Reader (Philadelphia, PA: Haworth Press, 1995), p. 3.

- ^ S. Lerer, Children's Literature: a Reader's History, from Aesop to Harry Potter (Chicago Il: University of Chicago Press, 2008), pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b c I. Opie and P. Opie, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1951, 2nd edn., 1997), pp. 30–1, 47–8, 128–9 and 299.

- ^ a b c d H. Carpenter and M. Prichard, The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), pp. 363–4, 383.

- ^ R. M. Dorson, The British Folklorists: a History (London, Taylor & Francis, 1999), p. 67.

- ^ J. Wardroper, Lovers, Rakes and Rogues, Amatory, Merry and Bawdy Verse from 1580 to 1830 (London: Shelfmark, 1995), p. 9.

- ^ M. Shiach, Discourse on Popular Culture: Class, Gender, and History in Cultural Analysis, 1730 to the Present, (Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 1989), p. 122 and 129.

- ^ E. Cray, The Erotic Muse: American Bawdy Songs (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1968) and G. Legman, The Horn Book: Studies in Erotic Folklore and Bibliography (New York: University Books, 1964).

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 216.

- ^ R. Pegg, Folk (Wildwood House: London, 1976), p. 76.

- ^ G. Legman, 'Erotic folk songs and international bibliography' Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of American Folklore (1990), 16/02/09.

- ^ G. Larsen, The Essential Guide to Irish Flute and Tin Whistle (Pacific, MO: Mel Bay Publications, 2003), p. 31.

- ^ E. Aldrich, S. N. Hammond, A. Russell. The Extraordinary Dance Book T B. 1826: An Anonymous Manuscript in Facsimile (Maesteg: Pendragon Press, 2000), p. 10.

- ^ a b J. Lee and M. R. Casey, Making the Irish American: History and Heritage of the Irish in the United States (New York University Press, 2006), p. 418.

- ^ C. R. Wilson and M. Calore, Music in Shakespeare: A Dictionary (London: Continuum International, 2005), p. 233.

- ^ M. Raven, ed., One Thousand English Country Dance Tunes (Michael Raven, 1999), p. 106.

- Oxford Companion to Music, vol. 2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 1203; M. Esses, Dance and Instrumental Diferencias in Spain During the 17th and Early 18th Centuries (Maesteg: Pendragon Press, 1992), p. 467.

- ^ R. Hutton, The Rise and Fall of Merry England, The Ritual Year 1400–1700 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), pp. 200–26.

- ^ T. Buckland, Dancing from Past to Present: Nation, Culture, Identities (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006), p. 199.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 232.

- ^ B. R. Smith, The Acoustic World of Early Modern England: Attending to the O-factor (Chicago Il: University of Chicago Press, 1999), p. 143.

- ^ P. H. Freedman, Images of the Medieval Peasant (Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 1999), p. 60.

- ^ G. Seal, The Outlaw Legend: A Cultural Tradition in Britain, America and Australia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 19–31.

- H. J. Stenning(London: Routledge, 1963), pp. 111–12.

- ^ a b c d V. de Sola Pinto and A. E. Rodway, The Common Muse: An Anthology of Popular British Ballad Poetry, XVth-XXth Century (Chatto & Windus, 1957), pp. 39–51, 145, 148–50, 159–60 and 250.

- ^ K. Binfield, ed., The Writings of the Luddites (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), pp. 98–100.

- ^ V. Gammon, 'The Grand Conversation: Napoleon and British Popular Balladry' Musical Traditions, retrieved 19/02/09.

- ^ J. Raven, The Urban & Industrial Songs of the Black Country and Birmingham (Michael Raven, 1977), pp. 52 and 61 and M. Vicinus, The Industrial Muse: A Study of Nineteenth Century British Working-class Literature (London: Taylor & Francis, 1974), p. 46.

- ^ 'Reviews' BBC Radio 2, http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio2/r2music/folk/reviews/englishrebelsongs.shtml, retrieved 19/02/09.

- ^ C. Irwin,'Power to the people; Aldermaston: The birth of the British protest song", 2008-08-10, 'The Guardian' https://www.theguardian.com/music/2008/aug/10/folk.politicsandthearts, retrieved on 19/02/09.

- ^ M. Willhardt, 'Available rebels and folk authenticities: Michelle Shocked and Billy Bragg' in I. Peddie, ed., The Resisting Muse: Popular Music and Social Protest (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), pp. 30–48.

- ^ R. A. Reuss and A. Green, Songs about Work: Essays in Occupational Culture (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1993), p. 335.

- ^ a b S. Hugill, Shanties from the Seven Seas: Shipboard Work-songs and Songs Used as Work-songs from the Great Days of Sail (Routledge, 1980). pp. 10–11 and 26.

- ^ a b J. Bird, Percy Grainger (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 125.

- ^ "What shall we do with a drunken sailor – Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders – World and traditional music | British Library – Sounds". sounds.bl.uk. Archived from the original on 2021-02-03. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "Shenandoah – Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders – World and traditional music | British Library – Sounds". sounds.bl.uk. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "All away Joe – Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders – World and traditional music | British Library – Sounds". sounds.bl.uk. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ A. Goodman and A. Tuck, eds, War and Border Societies in the Middle Ages (London: Routledge, 1992), pp. 6–7.

- ^ C. Mackay, ed., The Cavalier Songs and Ballads of England, from 1642 to 1684 (London: R. Griffin, 1863).

- ^ C. Mackay, ed., The Jacobite Songs and Ballads of Scotland from 1688 to 1746: With an Appendix of Modern Jacobite Songs (London: R. Griffin, 1861).

- ^ W. E. Studwell, The National and Religious Song Reader: Patriotic, Traditional, and Sacred Songs from Around the World (Philadelphia, PA: Haworth Press, 1996), p. 55.

- ^ J. S. Bratton, Acts of Supremacy: The British Empire and the Stage, 1790–1930 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1991), pp. 33–5.

- ^ S. Baring-Gould, An Old English Home and Its Dependencies (1898, Read books, 2008), p. 205.

- ^ P. M. Peek and K. Yankah, African Folklore: An Encyclopedia (London: Taylor & Francis, 2004), p. 520.

- ^ a b A. L. Lloyd, Folk song in England (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1967), pp. 323–8.

- ^ J. Shepherd, Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music, vol. 1: Media, Industry and Society (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003), p. 251.

- ^ 'Step Dancing', East Anglian Traditional Music Trust, http://www.eatmt.org.uk/stepdancing.htm, retrieved 16/02/09.

- ^ R. Vaughan Williams, Folk Songs from the Eastern Counties (London, 1908) and E. J. Moeran, Six Folk Songs from Norfolk (London, 1924) and E. J. Moeran, Six Suffolk Folk-Songs (London, 1932).

- ^ East Anglian Traditional Music Trust, http://www.eatmt.org.uk/profiles.htm, retrieved 16/02/09.

- ^ 'Peter Bellamy', Daily Telegraph, 26/9/08.

- ^ "Review of Tony Hall, Mr Universe", Living Tradition, http://www.folkmusic.net/htmfiles/webrevs/osmocd003.htm, retrieved 03/11/09.

- ^ 'History', Stone Angel, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-08-28. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), retrieved 04/02/09 and 'Spriguns of Tolgus', NME Artists, http://www.nme.com/artists/spriguns Archived 2012-01-11 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 02/02/09. - ^ Billy Bragg, official website, http://www.billybragg.co.uk/, retrieved 17/02/09 and Beth Orton, official website, "Beth Orton". Archived from the original on 2009-03-05. Retrieved 2009-02-25., retrieved 17/02/09.

- ^ East Anglian Traditional Music Trust, http://www.eatmt.org.uk/index.html, retrieved 16/02/09.

- ^ The Pipers' Gathering, http://www.pipersgathering.org/PB2004.shtml, retrieved 16/02/09.

- ^ R. B. Dobson and J. Taylor, Rymes of Robyn Hood, An Introduction to the English Outlaw (London: Book Club Associates, 1976), p. 14.

- ^ L. Jewitt, The Ballads & Songs of Derbyshire, with Illustrative Notes, and Examples of the Original Music, etc. (London, 1867); C. S. Burne, ed., Shropshire Folk-Lore: A Sheaf of Gleanings, from the Collections of Georgina F. Jackson, rpt. in 2 parts (Wakefield: EP Publishing, 1973–4).

- ^ P. O'Shaughnessy, ed. Twenty-One Lincolnshire Folk-Songs from the Manuscript Collection of Percy Grainger (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968).

- ^ R. Palmer, ed., Songs of the Midlands (Wakefield: EP Publishing, 1972); M. Raven, ed., The Jolly Machine: Songs of Industrial Protest and Social Discontent from the West Midlands (Stafford Spanish Guitar Centre, 1974); R. Palmer, ed., Birmingham Ballads: Facsimile Street Ballads (City of Birmingham Education Department, 1979).

- ^ Salut Live! http://www.salutlive.com/2007/07/martin-simpson-.html, retrieved 16/02/09.

- ^ Birmingham Conservatoire Folk Ensemble, Official website http://www.folkensemble.co.uk/, retrieved 16/02/09.

- ^ Folk and Roots, "Folk and Roots - 2009 Folk Festivals - Britain". Archived from the original on 2009-02-24. Retrieved 2009-02-25., retrieved 17/02/09.

- ^ a b c D. Gregory, The Songs of the People for Me: The Victorian Rediscovery of Lancashire Vernacular Song, Canadian Folk Music/Musique folklorique canadienne, 40 (2006), pp. 12–21.

- ^ Lancashire Folk, http://www.lancashirefolk.co.uk/Morris_Information.htm Archived 2016-03-26 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 16/02/09.

- ^ J. O. Halliwell, ed., Palatine Anthology: A Collection of Ancient Poems and Ballads Relating to Lancashire and Cheshire (London: Halliwell,1850) and his Palatine Garland, being a Selection of Ballads and Fragments Supplementary to the Palatine Anthology (London: Halliwell. 1850); J. Harland, ed., Ballads and Songs of Lancashire, Chiefly Older than the Nineteenth Century (London: Whittaker & Co., 1865. 2nd edn: London: 1875); William E. A. Axon, Folk Song and Folk-Speech of Lancashire: On the Ballads and Songs of the County Palatine, With Notes on the Dialect in which Many of them are Written, and an Appendix on Lancashire Folk-Lore (Manchester: Tubbs & Brook, 1887); John Harland & Thomas Turner Wilkinson, Lancashire Folk-lore (London: F. Warne, 1867); S. Gilpin, The Songs and Ballads of Cumberland and the Lake Country, with Biographical Sketches, Notes, and Glossary (2nd ed. 3 vols. London, 1874).

- ^ Folk North West, "Harry Boardman". Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2009-02-25., retrieved 16/02/09.

- ^ J, C. Falstaff, 'Roy Harper Longest Running Underground Act', Dirty Linen, 50 (Feb/Mar '94), http://www.dirtylinen.com/feature/50harper.html Archived 2007-10-21 at the Wayback Machine, 16/02/09 and Mike Harding, official website, http://www.mikeharding.co.uk/, retrieved 16/02/09.

- ^ WhileandMatthews official website "Biog". Archived from the original on 2008-12-04. Retrieved 2009-02-25., retrieved 08/01/09.

- ^ a b 'Festivals', Folk and Roots, "Folk and Roots - 2009 Folk Festivals - Britain". Archived from the original on 2009-02-24. Retrieved 2009-02-25., retrieved 08/01/09.

- ^ J. Bell, ed., Rhymes of Northern Bards: Being a Curious Collection of Old and New Songs and Poems Peculiar to the Counties of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Northumberland and Durham (1812), rpt. with an introduction by David Harker (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Frank Graham, 1971); B. J. Collingwood, and J. Stokoe, eds, Northumbrian Minstrelsy: A Collection of the Ballads, Melodies, and Small-Pipe Tunes of Northumbria (Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1882); and F. Kidson, English Folk-Song and Dance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1915, Read Books, 2008), p. 42.

- ^ A. Baines, Woodwind Instruments and Their History (Mineola, NY: Courier Dover, 1991), p. 328.

- ^ J. Reed, Border Ballads: A Selection (London: Routledge, 2004), p. 10.

- ^ Folk and Roots, http://www.folkandroots.co.uk/Venues_North_East.html Archived 2009-05-30 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 15/02/09.

- ^ R. Denselow, "Rachel Unthank and the Winterset, The Bairns", Guardian 24 August 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2007/aug/24/folk.shopping, retrieved 5/07/09.

- ^ J. Broadwood, Old English Songs, As Now Sung by the Peasantry of the Weald of Surrey and Sussex, and Collected by One Who Has Learnt Them by Hearing Them Sung Every Christmas from Early Childhood, by the Country People, Who Go About to the Neighbouring Houses, Singing, or 'Wassailing' as It Is Called, at that Season. The Airs Are Set to Music Exactly as They Are Now Sung, to Rescue Them from Oblivion, and to Afford a Specimen of Genuine Old English Melody: and the Words Are Given in Their Original Rough State, with an Occasional Slight Alteration To Render the Sense Intelligible (London, 1843).

- ^ G. B. Gardiner, Folk Songs from Hampshire (London: Novello, 1909) and A. E. Gillington, Eight Hampshire Folk Songs Taken from the Mouths of the Peasantry (London: Curwen, 1907); A. Williams, Folk songs of the Upper Thames (London, 1923) and C. Sharp, Cecil Sharp's Collection of English Folk Song, ed., Maud Karpeles, 2 vols (London: Oxford University Press, 1974).

- ^ Marcellus Laroon (artist) and Sean Shesgreen (editor), The Criers and Hawkers of London: Engravings and Drawings (Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 1990), p. 100.

- ^ A. White, Old London street cries ; and, The cries of to-day: with heaps of quaint cuts including hand-coloured frontispiece / Cries of to-day (London: Field & Tuer, The Leadenhall Press, 1885).

- ^ P. Humphries, Meet on the Ledge, a History of Fairport Convention (London: Virgin Publishing Ltd, 2nd edn., 1997), pp. 7–9.

- ^ 'Folk music in the City', Independent, 06/02/09, retrieved 03/12/15.

- ^ folkandhoney.co.uk. "Anna Tam | Folk Band | Gig Listings - Artist Listed on Folk and Honey". www.folkandhoney.co.uk. Retrieved 2021-01-21.

- ^ W. P. Merrick, Folk Songs from Sussex (English Folk Dance and Song Society, 1953).

- ^ J. R. Watson, T. Dudley-Smith, An Annotated Anthology of Hymns (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 108.

- ^ Copper Family Website, http://www.thecopperfamily.com/index.html, retrieved 13/02/09.

- Canadian Journal for Traditional Music(1997).

- ^ Obituaries, 'Bob Copper', 1 April 2004, The Independent, [1][dead link].

- ^ Folk and Roots, http://www.folkandroots.co.uk/Venues_Sussex.html Archived 2009-02-14 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 13/02/09; Folk in Sussex, "Folk in Sussex". Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2009-02-25., retrieved 13/02/09.

- ^ K. Mathieson, ed., Celtic music (San Francisco CA: Backbeat Books, 2001) pp. 88–95.

- ^ H. Woodhouse, Cornish Bagpipes: Fact or Fiction? (Truro: Truran, 1994).

- ^ R. Hays, C. McGee, S. Joyce & E. Newlyn, eds., Records of Early English Drama, Dorset & Cornwall (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999).

- ^ M. J. O'Connor, Ilow Kernow 3 (St. Ervan, Lyngham House, 2005).

- ^ M. J. O'Connor, An Overview of Recent Discoveries in Cornish Music, Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall (2007).

- ^ "Helston, Home of the Furry Dance". Borough of Helston.

- ^ H. F. Tucker, Epic: Britain's Heroic Muse 1790–1910 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 452.

- ^ a b c P. B. Ellis, The Cornish Language and Its Literature: A History (Routledge, 1974), pp. 92–4, 186 and 212.

- ^ D. Harvey, Celtic Geographies: Old Culture, New Times (London: Routledge, 2002), pp. 223–4.

- ^ Cornwall folk festival, http://www.cornwallfolkfestival.com/, retrieved 16/02/09.

- ^ C. Hole and Val Biro, British Folk Customs (London: Hutchinson, 1976), p. 133.

- ^ J. Shepherd, Media, Industry and Society (London: Continuum International, 2003), p. 44.

- ^ D. Manning, Vaughan Williams on Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 284.

- ^ Civil Tawney, http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/cyriltawney/enter.htm, retrieved 14/02/09.

- ^ 'Tony Rose' Independent on Sunday 12 June 2002, [2], retrieved 14/02/09.

- ^ Scrumpy and Western, http://www.scrumpyandwestern.co.uk/, retrieved 14/02/09.

- ^ L. Joint, 'Devon stars up for folk awards', BBC Devon, 01/06/09, http://www.bbc.co.uk/devon/content/articles/2009/01/06/folk_awards_2009_feature.shtml, retrieved 14/02/09.

- ^ Folk and Roots, "Folk and Roots - 2009 Folk Festivals - Britain". Archived from the original on 2009-02-24. Retrieved 2009-02-25., retrieved 14/02/09.

- ^ C. J. Sharp, Sword Dances of Northern England Together with the Horn Dance of Abbots Bromley, (Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2003).

- ^ C. J. D. Ingledew, Ballads and Songs of Yorkshire (London, 1860); C. Forshaw, Holyrod's Collection of Yorkshire Ballads (London, 1892).

- ^ N. Hudleston and M. Hudleston, Songs of the Ridings: The Yorkshire Musical Museum, ed., M. Gordon and R. Adams (Scarborough: G. A. Pindar and Son, 2001) and P. Davenport, ed., The South Riding Songbook: Songs from South Yorkshire and the North Midlands (South Riding Folk Network, 1998).

- ^ A. Kellett, On Ilkla Mooar baht 'at: the Story of the Song(Smith Settle, 1988).

- ^ F. J. Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads Dover Publications (New York, 1965), vol 1, p. 8.

- ^ a b R. Nidel, World Music: The Basics (London: Routledge, 2005), pp. 90–1.

- ^ Folk Roots, "Folk and Roots - the Guide to Yorkshire Folk Venues, Clubs, Resources and Artists". Archived from the original on 2013-02-09. Retrieved 2012-12-15., retrieved 12/02/09.

- ^ 'Folk songs of traditional Yorkshire to be celebrated on group's heritage website,' Yorkshire Post, http://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/video/Folk-songs-of-traditional-Yorkshire.3166419.jp, retrieved 12/02/09.

External links

- English Folk and Traditional Music

- Historical Notes on British Melodies

- Folk Music of England

- East Anglian Music Trust

- Pepys Ballad Archive

- Yorkshire Garland Group

- Field recordings by various collectors from the British Library (See under Europe)

- Hidden English: A Celebration of English Traditional Music Various Artists Topic Records TSCD600 (CD, UK, 1996)

| Folk music by era | |

|---|---|

| Subgenres and fusions | |

| Dance forms |

|

| Song forms | |

| Instruments | |

| Regional traditions | |

| Related articles |

|

| Art music | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of popular music | |||||||||||

| Traditional genres | |||||||||||

| Contemporary popular genres | |||||||||||

| Ethnic music | |||||||||||

| Media and performance |

| ||||||||||

| Regional music |

| ||||||||||

| Types and subgenres |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional traditions |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related articles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Folk song | |

|---|---|

| Folk dances |

|

| Instruments | |

| Tune types |

|

| Scales | |

| Relations | |

| General | |

|---|---|

| Folk song | |

| Instruments | |

| Tune types |

|

| Scales | |

| Relations | |

| Competitions |

|

| Music Awards | |

| Folk song | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folk dances | |||||||||||||

| Instruments | |||||||||||||

Common forms (by metre) |

| ||||||||||||

| Modes | |||||||||||||

| Characteristics | |||||||||||||

| Related music |

| ||||||||||||

| General | |

|---|---|

| Folk song | |

| Instruments | |

| Dance & Tune Types | |

| Scales | |

| Relations | |