Enver Pasha

İsmail Enver Ahmet Izzet Pasha | |

|---|---|

| Chief of the General Staff | |

| In office 8 January 1914 – 13 October 1918 | |

| Preceded by | Mehmed Hâdî Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Ahmed Izzet Pasha |

| Deputy commander-in-chief | |

| In office 8 January 1914 – 10 August 1918 | |

| Monarchs | Mehmed V Mehmed VI |

| Chief of staff of the commander-in-chief | |

| In office 10 August 1918 – 13 October 1918 | |

| Monarch | Mehmed VI |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 23 November 1881 |

| Battles/wars | |

İsmail Enver (

While stationed in Ottoman Macedonia, Enver joined the

As war minister and de facto Commander-in-Chief (despite his role as the de jure Deputy Commander-in-Chief, as the

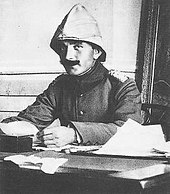

In the course of his career he was known by increasingly elevated titles as he rose through military ranks, including Enver

Early life and career

Enver was born in

Between 1903 and 1908 he was stationed in Ottoman Macedonia during the Macedonian Struggle, where he developed a reputation as an expert counterinsurgent (mostly Bulgarian bands). Fighting no less than 54 engagements, he became convinced of a need for reform of the Ottoman military.[21][22]

Joining the CUP

Enver, through the assistance of his uncle

In the early twentieth century some prominent Young Turk members such as Enver developed a strong interest in the ideas of Gustave Le Bon.[25] For example, Enver saw deputies as mediocre and in reference to Le Bon he thought that as a collective mind they had the potential to become dangerous and be the same as a despotic leader.[26] As the CUP shifted away from the ideas of members who belonged to the old core of the organisation to those of the newer membership, this change assisted individuals like Enver in gaining a larger profile in the Young Turk movement.[27]

In

Young Turk Revolution

On 3 July 1908, Niyazi, protesting the rule of

Enver sent an ultimatum to the Inspector General on 11 July 1908 and demanded that within 48 hours Abdul Hamid II issue a decree for CUP members that had been arrested and sent to Constantinople to be freed.

Aftermath

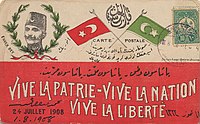

In the aftermath of the revolution Niyazi and Enver remained in the political background due to their youth and junior military ranks with both agreeing that photographs of them would not be distributed to the general public; however, this decision was rarely honoured.[44] Instead Niyazi and Enver as leaders of the revolution elevated their positions into near legendary status, with their images placed on postcards and distributed throughout the Ottoman state.[45][46] Toward the latter part of 1908, photographs of Niyazi and Enver had reached Constantinople and school children of the time played with masks on their faces that depicted the revolutionaries.[47] In other images produced of the time the sultan is presented in the centre flanked by Niyazi and Enver to either side.[30] As the actions of both men carried the appearance of initiating the revolution, Niyazi, an Albanian, and Enver, a Turk, later received popular acclaim as "heroes of freedom" (hürriyet kahramanları) and symbolised Albanian-Turkish cooperation.[48][49]

As a tribute to his role in the Young Turk Revolution that began the

Following the revolution Enver rose within the ranks of the Ottoman military and had an important role within army–committee relations.

Italo-Turkish War

In 1911, Italy launched an invasion of the Ottoman vilayet of Tripolitania (Trablus-i Garb, modern Libya), starting the Italo-Turkish War. Enver decided to join the defense of the province and left Berlin for Libya. There, he assumed the overall command after successfully mobilizing 20,000 troops.[56] Because of the outbreak of the Balkan Wars, however, Enver and other Ottoman generals in Libya were called back to Constantinople. This allowed Italy to take control of Libya. In 1912, thanks to his active role in the war, he was made lieutenant colonel.[57]

However, the loss of Libya cost the CUP in popularity, and it fell from government after rigging the

Balkan Wars and 1913 coup

In October 1912, the

In June 1913, however, the

In 1914, he became

World War I

Being able to communicate in

As soon as the war started, 31 October 1914, Enver ordered that all men of military age report to army recruiting offices. The offices were unable to handle the vast flood of men, and long delays occurred. This had the effect of ruining the crop harvest for that year.[59]

Battle of Sarikamish, 1914

Enver Pasha assumed command of the Ottoman forces arrayed against the Russians in the

Commanding the forces of the capital, 1915–1918

After his defeat at Sarıkamısh, Enver returned to Istanbul (Constantinople) and took command of the Turkish forces around the capital. He was confident that the capital was safe from any Allied attacks.

Yildirim

Enver's plan for

Army of Islam

During 1917, due to the

The Army of Islam, under the control of

However, after the Armistice of Mudros between Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire on 30 October, Ottoman troops were obliged to withdraw and replaced by the Triple Entente. These conquests in the Caucasus counted for very little in the war as a whole but they did however ensure that Baku remained within the boundaries of Azerbaijan while a part of the Soviet Union and later as an independent nation.

Armistice and exile

Faced with defeat, the Sultan dismissed Enver from his post as War Minister on 4 October 1918, while the rest of

Enver first attempted to link up with Halil and Nuri to reopen the Caucasus campaign, but his boat ran aground and hearing the army was demobilizing he gave up and went to Berlin like the other Unionists émigrés did. He settled in

Accompanying Mehmed Ali Sâmi, Enver's new pseudonym, was his Unionist comrade

Enver finally made it to Moscow in August 1920 (he came by land in the end). There he was well-received, and established contacts with representatives from

At Baku, Enver Pasha put in a sensational appearance. A whole hall full of Orientals broke into shouts, with scimitars and yataghans brandished aloft: 'Death to imperialism" All the same, genuine understanding with the Islamic world...was still difficult.[74]

Relations with Mustafa Kemal

Much has been written about the poor relations between Enver and Mustafa Kemal, two men who played pivotal roles in the Turkish history of the 20th century. Both hailed from the Balkans, and the two served together in North Africa during the wars preceding World War I, Enver being Mustafa Kemal's senior. Enver disliked Mustafa Kemal for his circumspect attitude toward the political agenda pursued by his Committee of Union and Progress, and regarded him as a serious rival.[75] Mustafa Kemal (later known as Atatürk) considered Enver to be a dangerous figure who might lead the country to ruin;[76] he criticized Enver and his colleagues for their policies and their involvement of the Ottoman Empire in World War I.[77][78] In the years of upheaval that followed the Armistice of October 1918, when Mustafa Kemal led the Turkish resistance to occupying and invading forces, Enver sought to return from exile, but his attempts to do so and join the military effort were blocked by the Ankara government under Mustafa Kemal.

Last years

On 30 July 1921, with the

According to David Fromkin:

However Enver's personal weaknesses reasserted themselves. He was a vain, strutting man who loved uniforms, medals and titles. For use in stamping official documents, he ordered a golden seal that described him as 'Commander-in-Chief of all the Armies of Islam, Son-in-Law of the Caliph and Representative of the Prophet.' Soon he was calling himself Emir of Turkestan, a practice not conducive to good relations with the Emir whose cause he served. At some point in the first half of 1922, the Emir of Bukhara broke off relations with him, depriving him of troops and much-needed financial support. The Emir of Afghanistan also failed to march to his aid.[80]

On 4 August 1922, as he allowed his troops to celebrate the

Fromkin writes:

There are several accounts of how Enver died. According to the most persuasive of them, when the Russians attacked he gripped his pocket Koran and, as always, charged straight ahead. Later his decapitated body was found on the field of battle. His Koran was taken from his lifeless fingers and was filed in the archives of the Soviet secret police.[86]

Enver's body was buried near Ab-i-Derya in Tajikistan.[87] In 1996, his remains were brought to Turkey and reburied at Abide-i Hürriyet (Monument of Liberty) cemetery in Şişli, Istanbul. He was re-buried on the 4 August, the anniversary of his death in 1922.[88][89] Enver Pasha's image remains controversial in Turkey, since Enver and Atatürk had a personal rivalry at the end of the Ottoman Empire and his memory was cultivated by the Kemalists.[89] But upon his body's arrival in Turkey, he was rehabilitated by the Turkish President Süleyman Demirel who held a speech acknowledging his contributions to Turkish nationalism.[89] Following renewed hostilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Nagorno Karabakh region in 2020, Enver Pasha's role during World War I was praised by Turkish President Erdoğan during an Azeri victory parade in Baku.[90] In 2023, Azerbaijani officials issued a map of the formerly Armenian Stepanakert, renaming one of the streets after Pasha.[91]

Family

After Enver's death, three of his four siblings,

Enver's sister Hasene Hanım married Nazım Bey. Nazım Bey, an aid-de-camp of Abdul Hamid II, survived an assassination attempt by Talaat during the 1908 Young Turk Revolution of which his brother-in-law Enver was a leader.[92] With Nazım, Hasene gave birth to Faruk Kenç (1910–2000), who would become a famous Turkish film director and producer.

Enver's other sister, Mediha Hanım (later Mediha Orbay; 1895–1983), married

Djevdet Bey who was the Vali of Van in 1915, was also a brother-in-law of his.[93]

Marriage

Around 1908, Enver Pasha became the subject of gossip about an alleged romance between him and Princess Iffet of Egypt. When this story reached Istanbul, the grand vizier, Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha decided to exploit Enver's marital eligibility by arranging a rapprochement between the Committee for Union and Progress and the imperial family.[94] After a careful search, the grand vizier chose the twelve old Naciye Sultan, a granddaughter of Sultan Abdulmejid I, as Enver's future bride. Both the grand vizier and Enver's mother then notified him of this decision. Enver had never seen Naciye, and he did not trust his mother's letters, since he suspected her of being enamored with the idea of having a princess as her daughter-in-law.[94]

Therefore, he asked a reliable friend, Ahmed Rıza Bey, who was a member of the Turkish Parliament to investigate. When the latter reported favorably on the prospective bride's education and beauty, as well as on the prospective dowry, Enver took a practical view of this marriage and accepted the arrangement.[95] Naciye had been previously engaged to Şehzade Abdurrahim Hayri.[96] However, Sultan Mehmed V broke off the engagement,[97] and in April 1909,[98] when Naciye was just twelve years old, engaged her to Enver, fifteen years older than her. Following the old Ottoman pattern of life and tradition, the engagement ceremony was celebrated in Enver's absence as he remained in Berlin.[99]

The marriage took place on 15 May 1911 in the Dolmabahçe Palace, and was performed by Şeyhülislam Musa Kazım Efendi. Head clerk of the sultan Halid Ziya Bey served as Naciye's deputy, and her witnesses were director of the imperial kitchen Galib Bey, and the personal physician of the sultan Hacı Ahmed Bey. Minister of war Mahmud Şevket Pasha served as Enver's deputy, and his witnesses were aide-de-camp of the sultan Binbaşı Re'fet Bey and chamberlain of the imperial gates Ahsan Bey.[100] The wedding took place about three years later on 5 March 1914[101] in the Nişantaşı Palace.[102][103] The couple were given one of the palaces of Kuruçeşme. The marriage was very happy.[104]

On 17 May 1917, Naciye gave birth to the couple's eldest child, a daughter,

After his death Naciye remarried with his brother Mehmed Kamil Killigil (1900–1962) in 1923, and had one other daughter, Rana Hanımsultan.[105]

Issue

By his wife, Enver had two daughters and a son:[105]

- Mahpeyker Hanımsultan (17 May 1917 – 3 April 2000). Married once, had a son.

- Türkan Hanımsultan (4 July 1919 – 25 December 1989). Married once, had a son.

- Sultanzade Ali Bey (29 September 1921 – 2 December 1971). Married twice, had a daughter.

In arts and culture

Enver Pasha plays an important role in The Golden House of Samarkand, a comic book by Hugo Pratt, from the Italian series Corto Maltese.

Works

- Enver authored a book in German, Enver Pascha «um Tripolis», which is his diaries during the war in Libya (1911–12).[107]

See also

- Young Turks

- Committee of Union and Progress

- Basmachi Revolt

- Armenian genocide

References

- ^ Komutanlığı, Harp Akademileri (1968), Harp Akademilerinin 120 Yılı (in Turkish), İstanbul, p. 46

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ISSN 2687-6515.

- ISBN 0203004930.

- ISBN 0812216164.

- OCLC 46785141.

- OCLC 1088605265.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - OCLC 935658756.

- ISBN 978-1-40949591-8.

The guilty main architects of the genocide Talaat Pasaha [...] and Enver Pasha...

- ISBN 978-1-40421825-3.

Enver Pasha, Mehmet Talat, and Ahmed Djemal were the three men who headed the CUP. They ran the Ottoman administration during World War I and planned the Armenian genocide.

- ISBN 978-0-41535385-4.

The new ruling triumvirate – Minister of Internal Affairs Talat Pasha; Minister of War Enver Pasha; and Minister of Navy Jemal Pasha – quickly established a de facto dictatorship. Under the rubric of the so-called Special Organization of the CUP, they directed, this trio would plan and oversee the Armenian genocide...

- ISBN 978-0-19-933420-9.

- ISBN 978-0-7658-0881-3.

- ISBN 978-0-19-533402-9.

- ISBN 978-0-300-04446-1.

- ^ JSTOR 4284039.

- ^ Kaylan, Muammer (2005), The Kemalists: Islamic Revival and the Fate of Secular Turkey, Prometheus Books, p. 75.

- ^ Akmese, Handan Nezir (2005), The Birth of Modern Turkey: The Ottoman Military and the March to WWI, IB Tauris, p. 44.

- ISBN 9780857718075.

- ^ a b c d Hanioğlu 2001, p. 266.

- ^ JSTOR 4282792.

- ^ Swanson, Glen W. (1980).pp.196–197

- S2CID 144491725.

- ^ a b c d e Zürcher 2014, p. 35.

- ^ Kansu 1997, p. 90.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, pp. 308, 311.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, p. 311.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, p. 291.

- ^ a b Hanioğlu 2001, p. 225.

- ^ a b Hanioğlu 2001, pp. 226.

- ^ ISBN 9781786720214.

- ^ ISBN 9781317802044.

- ^ Hale 2013, p. 35.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, p. 262.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d Hanioğlu 2001, p. 268.

- ISBN 9780198716020.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, pp. 228, 452. "Enver Bey's mother was from a mixed Albanian-Turkish family, and he could communicate in Albanian."

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, p. 228.

- ^ ISBN 9780857718075.

- ^ Gingeras 2016, p. 33.

- ^ a b Tzimos, Kyas (28 February 2018). "Έφτασε η ώρα της Πλατείας Ελευθερίας". Parallaxi.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, p. 275.

- ^ Bilici 2012, para. 26.

- ISBN 9781136101403.

- ^

Gingeras, Ryan (2016). Fall of the Sultanate: The Great War and the End of the Ottoman Empire 1908–1922. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 9780191663581.

- ^ Bilici 2012, para. 25.

- ^ Özen 2017, p. 28.

- ISBN 9781845112875.

- ISBN 9789004072626.

- ^ ISBN 9780761869948.

- ^ ISBN 9789759918095.

- ^ Bilici, Faruk (2012). "Le révolutionnaire qui alluma la mèche: Ahmed Niyazi Bey de Resne [Niyazi Bey from Resne: The Revolutionary who lit the Fuse]". Cahiers balkaniques. 40. para. 27.

- ISBN 9780791482971.

- ^ ISBN 9781477310939.

- ISBN 9780199771110.

- ^ Hakyemezoğlu, Serdar, Buhara Cumhuriyeti ve Enver Paşa (in Turkish), Ezberbozanbilgiler, archived from the original on 1 October 2011, retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ Enver Paşa Makalesi (in Turkish), Osmanlı Araştırmaları Sitesi, archived from the original on 1 April 2017, retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-691-15762-7.

- ^ ISBN 0-8050-6884-8.

- ISBN 0-88738-338-6.

- ISBN 0-415-94246-2

- ISBN 1-85109-420-2

- ISBN 0-06-019840-0.

- ISBN 0-8050-7932-7.

- ^ Moorehead 1997, p. 79.

- ^ Moorehead 1997, p. 166–68.

- ^ Woodward 1998, pp. 160–1.

- ^ Homa Katouzian, State and Society in Iran: The Eclipse of the Qajars and the Emergence of the Pahlavis, (I.B. Tauris, 2006), 141.

- ^ Refuting Genocide, U Mich, archived from the original on 4 April 2002.

- ^ a b Wheeler-Bennett, John (1967), The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, p. 126.

- ^ Hanioğlu, Şükrü. "Enver Paşa". İslâm Ansiklopedisi.

- ^ "147 ) UÇTU UÇTU, ENVER PAŞA UÇTU !." Tarihten Anektotlar. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Moorehead 1997, p. 300.

- ISBN 0-86316-070-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-61592-897-2.

- ^ ISBN 90-04-07262-4.

- ISBN 978-90-04-17434-4.

- ISBN 978-1-55587-954-9.

- ISBN 0192851667.

- ^ Fromkin 1989, p. 487

- ^ Kandemir, Feridun (1955), Enver Paşa'nın Son Gũnleri (in Turkish), Gũven Yayınevi, pp. 65–69.

- ISBN 978-975-8845-28-6.

- ^ Melkumov, Ya. A. (1960), Туркестанцы [Memoirs] (in Russian), Moscow, pp. 124–127

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ^ "Civil War in Central Asia", Ratnik

- ^ Гайк Айрапетян. "Акоп Мелькумов". HayAdat.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ Fromkin 1989, p. 488

- ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ "Turk Enver Pasha headed for reburial". UPI. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85649-867-8.

- ^ Mirror-Spectator, The Armenian (11 December 2020). "At Baku Victory Parade, Aliyev Calls Yerevan, Zangezur, Sevan Historical Azerbaijani Lands, Erdogan Praises Enver Pasha". The Armenian Mirror-Spectator. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Vincent, Faustine (4 October 2023). "Azerbaijan reissues Nagorno-Karabakh map with street named after Turkish leader of 1915 Armenian genocide". Le Monde.fr. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-135-26705-6.

- S2CID 198820452.

- ^ a b Rorlich, Azade-Ayse (1972). Enver Pasha and the Bolshevik Revolution. University of Wisconsin—Madison. pp. Pages=9–10.

- ^ Rorlich 1972, pp. 10–11.

- ISBN 978-6-054-81261-5.

- ^ Altındal, Meral (1993). Osmanlı'da harem. Altın Kitaplar Yayınevi. p. 138.

- ISBN 978-1-850-43797-0.

- ^ Rorlich 1972, p. 11.

- ^ Milanlıoğlu, Neval (2011). Emine Naciye Sultan'ın Hayatı (1896–1957) (in Turkish). Marmara University Institute of Social Sciences. pp. Pages=30–31.

- ^ Milanlıoğlu 2011, p. 57.

- ISBN 978-0-190-49244-1.

- ^ Tarih ve toplum: aylık ansiklopedik dergi, Volume 26. İletişim Yayınları/Perka A. Ş. 1934. p. 171.

- ISBN 978-6-054-33739-2.

- ^ a b c d e ADRA, Jamil (2005). Genealogy of the Imperial Ottoman Family 2005. pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Rorlich 1972, p. 79.

- ^ "Un ouvrage d'Enver Pacha". Servet-i-Funoun Partie Française (1400): 2. 4 July 1917.

Sources

- Fromkin, David (1989), A Peace to End All Peace, Avon Books

- Kansu, Aykut (1997). The Revolution of 1908 in Turkey. Brill. ISBN 9789004107915.

- ISBN 1-85326-675-2.

- Woodward, David R (1998), Field Marshal Sir William Robertson, Westport, ISBN 0-275-95422-6.

Further reading

- Haley, Charles D. (January 1994). "The Desperate Ottoman: Enver Paşa and the German Empire – I". JSTOR 4283613.

External links

- Enver's biography

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 31 (12th ed.). 1922. p. 5.

- Enver's declaration at the Baku Congress of the Peoples of the East 1920

- Interview with Enver Pasha by Henry Morgenthau – American Ambassador to Constantinople (Istanbul) 1915

- Biography of Enver Pasha at Turkey in the First World War website

- Personal belongings of Enver Pasha

- Ismail Enver Pasha (1881–1922) Archived 5 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Newspaper clippings about Enver Pasha in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW