Environmental impacts of animal agriculture

It has been suggested that Discuss ) Proposed since March 2024. |

The environmental impacts of animal agriculture vary because of the wide variety of

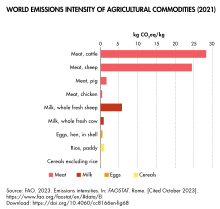

Animal agriculture is a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. Cows, sheep, and other ruminants digest their food by enteric fermentation, and their burps are the main source of methane emissions from land use, land-use change, and forestry. Together with methane and nitrous oxide from manure, this makes livestock the main source of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture.[1] A significant reduction in meat consumption is essential to mitigate climate change, especially as the human population increases by a projected 2.3 billion by the middle of the century.[2][3]

Consumption and production trends

| Categories | Contribution of farmed animal product [%] |

|---|---|

| Calories | 18

|

| Proteins | 37

|

| Land use | 83

|

| Greenhouse gases | 58

|

| Water pollution | 57

|

| Air pollution | 56

|

| Freshwater withdrawals | 33

|

Multiple studies have found that increases in meat consumption are currently associated with

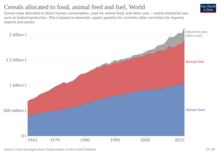

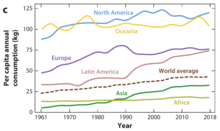

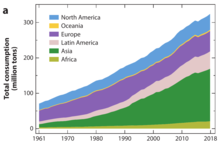

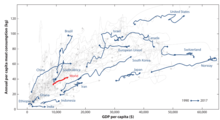

Changes in demand for meat will influence how much is produced, thus changing the environmental impact of meat production. It has been estimated that global meat consumption may double from 2000 to 2050, mostly as a consequence of the increasing world population, but also partly because of increased per capita meat consumption (with much of the per capita consumption increase occurring in the developing world).[8] The human population is projected to grow to 9 billion by 2050, and meat production is expected to increase by 40%.[9] Global production and consumption of poultry meat have been growing recently at more than 5% annually.[8] Meat consumption typically increases as people and countries get richer.[10] Trends also vary among livestock sectors. For example, global pork consumption per capita has increased recently (almost entirely due to changes in consumption within China), while global consumption per capita of ruminant meats has been declining.[8]

Resource use

Food production efficiency

About 85% of the world's soybean crop is processed into meal and vegetable oil, and virtually all of that meal is used in animal feed.[11] Approximately 6% of soybeans are used directly as human food, mostly in Asia.[11]

For every 100 kilograms of food made for humans from crops, 37 kilograms byproducts unsuitable for direct human consumption are generated. [12] Many countries then repurpose these human-inedible crop byproducts as livestock feed for cattle.[13] Raising animals for human consumption accounts for approximately 40% of total agricultural output in industrialized nations.[14] Moreover, the efficiency of meat production varies depending on the specific production system, as well as the type of feed. It may require anywhere from 0.9 and 7.9 kilograms of grain to produce 1 kilogram of beef, between 0.1 to 4.3 kilograms of grain to produce 1 kilogram of pork, and 0 to 3.5 kilograms of grains to produce 1 kilogram of chicken.[15][16]

FAO estimates, however, that about 2 thirds of the pasture area used by livestock is not convertible to crop-land.[15][16]

Major corporations purchase land in different developing nations in Latin America and Asia to support large-scale production of animal feed crops, mainly corn and soybeans. This practice reduces the amount of land available for growing crops that are fit for human consumption in these countries, putting the local population at risk of food security.[17]

According to a study conducted in Jiangsu, China, individuals with higher incomes tend to consume more food than those with lower incomes and larger families. Consequently, it is unlikely that those employed in animal feed production in these regions do not consume the animals that eat the crops they produce. The lack of space for growing crops for consumption, coupled with the need to feed larger families, only exacerbates their food insecurity.[18]

According to FAO, crop-residues and by-products account for 24% of the total dry matter intake of the global livestock sector.[15][16] A 2018 study found that, "Currently, 70% of the feedstock used in the Dutch feed industry originates from the food processing industry."[19] Examples of grain-based waste conversion in the United States include feeding livestock the distillers grains (with solubles) remaining from ethanol production. For the marketing year 2009–2010, dried distillers grains used as livestock feed (and residual) in the US was estimated at 25.5 million metric tons.[20] Examples of waste roughages include straw from barley and wheat crops (edible especially to large-ruminant breeding stock when on maintenance diets),[21][22][23] and corn stover.[24][25]

Land use

| Food Types | Land Use (m2year per 100g protein) |

|---|---|

| Lamb and mutton | 185

|

| Beef | 164

|

| Cheese | 41

|

| Pork | 11

|

| Poultry | 7.1

|

Eggs

|

5.7

|

| Farmed fish | 3.7

|

| Groundnuts | 3.5

|

Peas

|

3.4

|

| Tofu | 2.2

|

Permanent meadows and pastures, grazed or not, occupy 26% of the Earth's ice-free terrestrial surface.[15][16] Feed crop production uses about one-third of all arable land.[15][16] More than one-third of U.S. land is used for pasture, making it the largest land-use type in the contiguous United States.[27]

In many countries, livestock graze from the land which mostly cannot be used for growing human-edible crops, as seen by the fact that there is three times as much agricultural land[28] as arable land.[29]

A 2023 study found that a

Free-range animal production, particularly beef production, has also caused tropical deforestation because it requires land for grazing.[31] The livestock sector is also the primary driver of deforestation in the Amazon, with around 80% of all deforested land being used for cattle farming.[32][33] Additionally, 91% of deforested land since 1970 has been used for cattle farming.[34][35] Research has argued that a shift to meat-free diets could provide a safe option to feed a growing population without further deforestation, and for different yields scenarios.[36] However, according to FAO, grazing livestock in drylands “removes vegetation, including dry and flammable plants, and mobilizes stored biomass through depositions, which is partly transferred to the soil, improving fertility. Livestock is key to creating and maintaining specific habitats and green infrastructures, providing resources for other species and dispersing seeds”.[37]

Water use

Globally, the amount of water used for agricultural purposes exceeds any other industrialized purpose of water consumption.[38] About 80% of water resources globally are used for agricultural ecosystems. In developed countries, up to 60% of total water consumption can be used for irrigation; in developing countries, it can be up to 90%, depending on the region's economic status and climate. According to the projected increase in food production by 2050, water consumption would need to increase by 53% to satisfy the world population's demands for meat and agricultural production.[38]

Groundwater depletion is a concern in some areas because of sustainability issues (and in some cases, land subsidence and/or saltwater intrusion).[39] A particularly important North American example of depletion is the High Plains (Ogallala) Aquifer, which underlies about 174,000 square miles in parts of eight states of the USA and supplies 30 percent of the groundwater withdrawn for irrigation there.[40] Some irrigated livestock feed production is not hydrologically sustainable in the long run because of aquifer depletion. Rainfed agriculture, which cannot deplete its water source, produces much of the livestock feed in North America. Corn (maize) is of particular interest, accounting for about 91.8% of the grain fed to US livestock and poultry in 2010.[41]: table 1–75 About 14 percent of US corn-for-grain land is irrigated, accounting for about 17% of US corn-for-grain production and 13% of US irrigation water use,[42][43] but only about 40% of US corn grain is fed to US livestock and poultry.[41]: table 1–38 Irrigation accounts for about 37% of US withdrawn freshwater use, and groundwater provides about 42% of US irrigation water.[44] Irrigation water applied in the production of livestock feed and forage has been estimated to account for about 9 percent of withdrawn freshwater use in the United States.[45]

Almost one-third of the water used in the western United States goes to crops that feed cattle.[46] This is despite the claim that withdrawn surface water and groundwater used for crop irrigation in the US exceeds that for livestock by about a ratio of 60:1.[44] This excessive use of river water distresses ecosystems and communities, and drives scores of species of fish closer to extinction during times of drought.[47]

A 2023 study found that a

A study in 2019 focused on linkages between water usage and animal agricultural practices in China.[48] The results of the study showed that water resources were being used primarily for animal agriculture; the highest categories were animal husbandry, agriculture, slaughtering and processing of meat, fisheries, and other foods. Together they accounted for the consumption of over 2400 billion m3 embodied water, roughly equating to 40% of total embodied[clarification needed] water by the whole system.[48] This means that more than one-third of China's entire water consumption is being used for food processing purposes, and mostly for animal agricultural practices.

| Foodstuff | Litres per | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kilocalorie | gram of protein |

kg of foodstuff |

gram of fat | |

| Sugar crops | 0.69 | N/A | 197 | N/A |

| Vegetables | 1.34 | 26 | 322 | 154 |

| Starchy roots | 0.47 | 31 | 387 | 226 |

| Fruits | 2.09 | 180 | 962 | 348 |

| Cereals | 0.51 | 21 | 1644 | 112 |

| Oil crops | 0.81 | 16 | 2364 | 11 |

| Pulses | 1.19 | 19 | 4055 | 180 |

| Nuts | 3.63 | 139 | 9063 | 47 |

| Milk | 1.82 | 31 | 1020 | 33 |

| Eggs | 2.29 | 29 | 3265 | 33 |

| Chicken meat | 3.00 | 34 | 4325 | 43 |

| Butter | 0.72 | N/A | 5553 | 6.4 |

| Pig meat | 2.15 | 57 | 5988 | 23 |

| Sheep/goat meat | 4.25 | 63 | 8763 | 54 |

| Bovine meat | 10.19 | 112 | 15415 | 153 |

Water pollution

Water pollution due to animal waste is a common problem in both developed and developing nations.[14] The USA, Canada, India, Greece, Switzerland and several other countries are experiencing major environmental degradation due to water pollution via animal waste.[50]: Table I-1 Concerns about such problems are particularly acute in the case of CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations). In the US, a permit for a CAFO requires the implementation of a plan for the management of manure nutrients, contaminants, wastewater, etc., as applicable, to meet requirements under the Clean Water Act.[51] There were about 19,000 CAFOs in the US as of 2008.[52] In fiscal 2014, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) concluded 26 enforcement actions for various violations by CAFOs.[53]

A 2023 study found that a

Effective use of fertilizer is crucial to accelerate the growth of animal feed production, which in turn increases the amount of feed available for livestock.[54] However, excess fertilizer can enter water bodies via runoff after rainfall, resulting in eutrophication.[55] The addition of nitrogen and phosphorus can cause the rapid growth of algae, also known as an algae bloom. The reduction of oxygen and nutrients in the water caused by the growth of algae ultimately leads to the death of other species in the ecosystem. This ecological harm has consequences not only for the native animals in the affected water body but also for the water supply for people.[54]

To dispose of animal waste and other pollutants, animal production farms often spray manure (often contaminated with potentially toxic bacteria) onto empty fields, called "spray-fields", via sprinkler systems. The toxins within these spray-fields oftentimes run into creeks, ponds, lakes, and other bodies of water, contaminating bodies of water. This process has also led to the contamination of drinking water reserves, harming the environment and citizens alike.[56]

Air pollution

| Food Types | Acidifying Emissions (g SO2eq per 100g protein) |

|---|---|

| Beef | 343.6

|

| Cheese | 165.5

|

| Pork | 142.7

|

| Lamb and Mutton | 139.0

|

| Farmed Crustaceans | 133.1

|

| Poultry | 102.4

|

| Farmed Fish | 65.9

|

Eggs

|

53.7

|

| Groundnuts | 22.6

|

Peas

|

8.5

|

| Tofu | 6.7

|

Animal agriculture is a cause of harmful particulate matter pollution in the atmosphere. This type of production chain produces byproducts; endotoxin, hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, and particulate matter (PM), such as dust,[57][58] all of which can negatively impact human respiratory health.[59] Furthermore, methane and CO2—the primary greenhouse gas emissions associated with meat production—have also been associated with respiratory diseases like asthma, bronchitis, and COPD.[60]

A study found that concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) could increase perceived asthma-like symptoms for residents within 500 meters.[61] Concentrated hog feeding operations release air pollutants from confinement buildings, manure holding pits, and land application of waste. Air pollutants from these operations have caused acute physical symptoms, such as respiratory illnesses, wheezing, increased breath rate, and irritation of the eyes and nose.[62][63][64] That prolonged exposure to airborne animal particulate, such as swine dust, induces a large influx of inflammatory cells into the airways.[65] Those in close proximity to CAFOs could be exposed to elevated levels of these byproducts, which may lead to poor health and respiratory outcomes.[66] Additionally, since CAFOs tend to be located in primarily rural and low-income communities, low-income people are disproportionately affected by these environmental health consequences. [1]

Especially when modified by high temperatures, air pollution can harm all regions, socioeconomic groups, sexes, and age groups. Approximately seven million people die from air pollution exposure every year. Air pollution often exacerbates respiratory disease by permeating into the lung tissue and damaging the lungs.[67]

Despite the wealth of environmental consequences listed above, local US governments tend to support the harmful practices of the animal production industry due to its strong economic benefits. Due to this protective legislature, it is extremely difficult for activists to regulate industry practices and diminish environmental impacts. [68]

Climate change aspects

Energy consumption

An important aspect of energy use in livestock production is the energy consumption that the animals contribute. Feed Conversion Ratio is an animal's ability to convert feed into meat. The Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR) is calculated by taking the energy, protein, or mass input of the feed divided by the output of meat provided by the animal. A lower FCR corresponds with a smaller requirement of feed per meat output, and therefore the animal contributes less GHG emissions. Chickens and pigs usually have a lower FCR compared to ruminants.[69]

Intensification and other changes in the livestock industries influence energy use, emissions, and other environmental effects of meat production.[70]

Manure can also have environmental benefits as a renewable energy source, in digester systems yielding biogas for heating and/or electricity generation. Manure biogas operations can be found in Asia, Europe,[71][72] North America, and elsewhere.[73] System cost is substantial, relative to US energy values, which may be a deterrent to more widespread use. Additional factors, such as odour control and carbon credits, may improve benefit-to-cost ratios.[74] Manure can be mixed with other organic wastes in anaerobic digesters to take advantage of economies of scale. Digested waste is more uniform in consistency than untreated organic wastes, and can have higher proportions of nutrients that are more available to plants, which enhances the utility of digestate as a fertiliser product.[75] This encourages circularity in meat production, which is typically difficult to achieve due to environmental and food safety concerns.

Greenhouse gas emissions

Cows, sheep and other ruminants digest their food by enteric fermentation, and their burps are the main methane emissions from land use, land-use change, and forestry: together with methane and nitrous oxide from manure this makes livestock the main source of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture.[1]

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report in 2022 stated that: "Diets high in plant protein and low in meat and dairy are associated with lower GHG emissions. [...] Where appropriate, a shift to diets with a higher share of plant protein, moderate intake of animal-source foods and reduced intake of saturated fats could lead to substantial decreases in GHG emissions. Benefits would also include reduced land occupation and nutrient losses to the surrounding environment, while at the same time providing health benefits and reducing mortality from diet-related non-communicable diseases."[76]

A 2023 study found that a

According to a 2022 study quickly stopping animal agriculture would provide half the GHG emission reduction needed to meet the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 2 °C.[3]

The global food system is responsible for one-third of the global anthropogenic GHG emissions,[77][78] of which meat accounts for nearly 60%.[31][79]

In the context of global GHG emissions, food production within the global food system accounts for approximately 26%. Breaking it down, livestock and fisheries contribute 31%, whereas crop production, land use, and supply chains add 27%, 24%, and 18% respectively to the emissions.[80]

Mitigation options

In addition to reduced consumption, emissions can also be reduced by changes in practice. One study found that shifting compositions of current feeds, production areas, and informed land restoration could enable greenhouse gas emissions reductions of 34–85% annually (612–1,506 megatons CO2 equivalent per year) without increasing costs or changing diets.[85]

Producers can reduce ruminant enteric fermentation using genetic selection,

Measures that increase state revenues from meat consumption/production could enable the use of these funds for related research and development and "to cushion social hardships among low-income consumers". Meat and livestock are important sectors of the contemporary socioeconomic system, with livestock value chains employing an estimated >1.3 billion people.[5]

Sequestering carbon into soil is currently not feasible to cancel out planet-warming emissions caused by the livestock sector. The global livestock annually emits 135 billion metric tons of carbon, way more than can be returned to the soil.[97] Despite of this the idea of sequestering carbon to the soil is currently advocated by livestock industry as well as grassroots groups.[98]

Effects on ecosystems

Soils

Grazing can have positive or negative effects on rangeland health, depending on management quality,[99] and grazing can have different effects on different soils[100] and different plant communities.[101] Grazing can sometimes reduce, and other times increase, biodiversity of grassland ecosystems.[102][103] In beef production, cattle ranching helps preserve and improve the natural environment by maintaining habitats that are well suited for grazing animals.[104] Lightly grazed grasslands also tend to have higher biodiversity than overgrazed or non-grazed grasslands.[105]

Overgrazing can decrease

Grazing can affect the

In Canada, a review highlighted that the methane and nitrous oxide emitted from manure management comprised 17% of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions, while nitrous oxide emitted from soils after application of manure, accounted for 50% of total emissions.[118]

Manure provides environmental benefits when properly managed. Deposition of manure on pastures by grazing animals is an effective way to preserve soil fertility. Many nutrients are recycled in crop cultivation by collecting animal manure from barns and concentrated feeding sites, sometimes after composting. For many areas with high livestock density, manure application substantially replaces the application of synthetic fertilizers on surrounding cropland.[119] Manure is also spread on forage-producing land that is grazed, rather than cropped.[43]

Also, small-ruminant flocks in North America (and elsewhere) are sometimes used on fields for removal of various crop residues inedible by humans, converting them to food. Small ruminants, such as sheep and goats, can control some invasive or

Biodiversity

Meat production is considered one of the prime factors contributing to the current

Grazing (especially overgrazing) may detrimentally affect certain wildlife species, e.g. by altering cover and food supplies. The growing demand for meat is contributing to significant biodiversity loss as it is a significant driver of deforestation and habitat destruction; species-rich habitats, such as significant portions of the Amazon region, are being converted to agriculture for meat production.[131][125][132] World Resource Institute (WRI) website mentions that "30 percent of global forest cover has been cleared, while another 20 percent has been degraded. Most of the rest has been fragmented, leaving only about 15 percent intact."[133] WRI also states that around the world there is "an estimated 1.5 billion hectares (3.7 billion acres) of once-productive croplands and pasturelands – an area nearly the size of Russia – are degraded. Restoring productivity can improve food supplies, water security, and the ability to fight climate change."[134] Around 25% to nearly 40% of global land surface is being used for livestock farming.[129][135]

A 2022 report from

A 2023 study found that a

In North America, various studies have found that grazing sometimes improves habitat for elk,[137] blacktailed prairie dogs,[138] sage grouse,[139] and mule deer.[140][141] A survey of refuge managers on 123 National Wildlife Refuges in the US tallied 86 species of wildlife considered positively affected and 82 considered negatively affected by refuge cattle grazing or haying.[142] The kind of grazing system employed (e.g. rest-rotation, deferred grazing, HILF grazing) is often important in achieving grazing benefits for particular wildlife species.[143]

The biologists Rodolfo Dirzo, Gerardo Ceballos, and Paul R. Ehrlich write in an opinion piece for Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B that reductions in meat consumption "can translate not only into less heat, but also more space for biodiversity." They insist that it is the "massive planetary monopoly of industrial meat production that needs to be curbed" while respecting the cultural traditions of indigenous peoples, for whom meat is an important source of protein.[144]

Aquatic ecosystems

| Food type | Eutrophying emissions (g PO43-eq per 100g protein) |

|---|---|

| Beef | 301.4

|

| Farmed Fish | 235.1

|

| Farmed Crustaceans | 227.2

|

| Cheese | 98.4

|

| Lamb and Mutton | 97.1

|

| Pork | 76.4

|

| Poultry | 48.7

|

Eggs

|

21.8

|

| Groundnuts | 14.1

|

Peas

|

7.5

|

| Tofu | 6.2

|

Global agricultural practices are known to be one of the main reasons for environmental degradation. Animal agriculture worldwide encompasses 83% of farmland (but only accounts for 18% of the global calorie intake), and the direct consumption of animals as well as over-harvesting them is causing environmental degradation through habitat alteration, biodiversity loss, climate change, pollution, and trophic interactions.[145] These pressures are enough to drive biodiversity loss in any habitat, however freshwater ecosystems are showing to be more sensitive and less protected than others and show a very high effect on biodiversity loss when faced with these impacts.[145]

In the Western United States, many stream and riparian habitats have been negatively affected by livestock grazing. This has resulted in increased phosphates, nitrates, decreased dissolved oxygen, increased temperature, turbidity, and eutrophication events, and reduced species diversity.[146][147] Livestock management options for riparian protection include salt and mineral placement, limiting seasonal access, use of alternative water sources, provision of "hardened" stream crossings, herding, and fencing.[148][149] In the Eastern United States, a 1997 study found that waste release from pork farms has also been shown to cause large-scale eutrophication of bodies of water, including the Mississippi River and Atlantic Ocean (Palmquist, et al., 1997).[150] In North Carolina, where the study was done, measures have since been taken to reduce the risk of accidental discharges from manure lagoons, and since then there has been evidence of improved environmental management in US hog production.[151] Implementation of manure and wastewater management planning can help assure low risk of problematic discharge into aquatic systems.[151]

In Central-Eastern Argentina, a 2017 study found large quantities of metal pollutants (chromium, copper, arsenic and lead) in their freshwater streams, disrupting the aquatic biota.[152] The level of chromium in the freshwater systems exceeded 181.5× the recommended guidelines necessary for survival of aquatic life, while lead was 41.6×, copper was 57.5×, and arsenic exceeded 12.9×. The results showed excess metal accumulation due to agricultural runoff, the use of pesticides, and poor mitigation efforts to stop the excess runoff.[152]

Animal agriculture contributes to global warming, which leads to ocean acidification. This occurs because as carbon emissions increase, a chemical reaction occurs between carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and ocean water, causing seawater acidification.[153] The process is also known as the dissolution of inorganic carbon in seawater.[154] This chemical reaction creates an environment that makes it difficult for calcifying organisms to produce protective shells and causes seagrass overpopulation.[155] A reduction in marine life can have an adverse effect on people’s way of life, since limited sea life may reduce food availability and reduce coastal protection against storms.[156]

Effects on antibiotic resistance

While levels of use vary dramatically from country to country, for example some Northern European countries use very low quantities to treat animals compared with humans,[163][164] worldwide an estimated 73% of antimicrobials (mainly antibiotics) are consumed by farm animals.[165] Furthermore, a 2015 study also estimates that global agricultural antibiotic usage will increase by 67% from 2010 to 2030, mainly from increases in use in developing BRIC countries.[166]

Increased antibiotic use is a matter of concern as

There are concerns about meat production's potential to spread diseases as an environmental impact.[178][179][180][181]

Alternatives to meat production and consumption

A study shows that

Meat reduction and health

With care, meat can be substituted in most diets with a wide variety of foods such as

Nevertheless, observational studies find beneficial effects from plant-based diets (compared to consumption of meat products) on health and mortality rates.[200][5][201][202][203]

Meat-reduction strategies

Strategies for implementing meat-reduction among populations include large-scale education and awareness building to promote more sustainable consumption styles. Other types of policy interventions could accelerate these shifts and might include "restrictions or fiscal mechanisms such as [meat] taxes".[5] In the case of fiscal mechanisms, these could be based on forms of scientific calculation of external costs (externalities currently not reflected in any way in the monetary price)[204] to make the polluter pay, e.g. for the damage done by excess nitrogen.[205] In the case of restrictions, this could be based on limited domestic supply or Personal (Carbon) Allowances (certificates and credits which would reward sustainable behavior).[206][207]

Relevant to such a strategy, estimating the environmental impacts of food products in a standardized way – as has been done with a dataset of more than 57,000 food products in supermarkets – could also be used to inform consumers or in policy, making consumers more aware of the environmental impacts of animal-based products (or requiring them to take such into consideration).[208][209]

Young adults that are faced with new physical or social environments (for example, moving away from home) are also more likely to make dietary changes and reduce their meat intake.[210] Another strategy includes increasing the prices of meat while also reducing the prices of plant-based products, which could show a significant impact on meat-reduction.[211]

A reduction in meat portion sizes could potentially be more beneficial than cutting out meat entirely from ones diet, according to a 2022 study.[210] This study revolved around young Dutch adults, and showed that the adults were more reluctant to cut out meat entirely to make the change to plant-based diets due to habitual behaviours. Increasing and improving plant-based alternatives, as well as the education about plant-based alternatives, proved to be one of the most effective ways to combat these behaviours. The lack of education about plant-based alternatives is a road-block for most people - most adults do not know how to properly cook plant-based meals or know the health risks/benefits associated with a vegetarian diet - which is why education among adults is important in meat-reduction strategies.[210][211]

In the Netherlands, a meat tax of 15% to 30% could show a reduction of meat consumption by 8% to 16%.[210] as well as reducing the amount of livestock by buying out farmers.[212] In 2022, the city of Haarlem, Netherlands announced that advertisements for factory-farmed meat will be banned in public places, starting in 2024.[213]

A 2022 review concluded that "low and moderate meat consumption levels are compatible with the climate targets and broader sustainable development, even for 10 billion people".[5]

In June 2023, the European Commission's Scientific Advice Mechanism published a review of all available evidence and accompanying policy recommendations to promote sustainable food consumption and reducing meat intake. They reported that the evidence supports policy interventions on pricing (including "meat taxes, and pricing products according to their environmental impacts, as well as lower taxes on healthy and sustainable alternatives"), availability and visibility, food composition, labelling and the social environment.[214] They also stated:

People choose food not just through rational reflection, but also based on many other factors: food availability, habits and routines, emotional and impulsive reactions, and their financial and social situation. So we should consider ways to unburden the consumer and make sustainable, healthy food an easy and affordable choice.

By type of animal

Cattle

Pigs

See also

- Agroecology

- Animal-free agriculture

- Animal–industrial complex

- Carbon tax

- Meat price

- Cultured meat

- Economic vegetarianism

- Factory farming divestment

- Environmental impact of agriculture

- Environmental impact of fishing

- Environmental vegetarianism

- Food vs. feed

- Stranded assets in the agriculture and forestry sector

- Sustainable agriculture

- Sustainable diet

- Veganism

References

- ^ a b Mitigation of Climate Change: Full report (Report). IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. 2022. 7.3.2.1 page 771.

- ^ a b c Carrington, Damian (October 10, 2018). "Huge reduction in meat-eating 'essential' to avoid climate breakdown". The Guardian. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ S2CID 246499803.

- ^ Damian Carrington, "Avoiding meat and dairy is ‘single biggest way’ to reduce your impact on Earth ", The Guardian, 31 May 2018 (page visited on 19 August 2018).

- ^ ISSN 1941-1340.

- ^ Devlin, Hannah (July 19, 2018). "Rising global meat consumption 'will devastate environment'". The Guardian. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- S2CID 49895246.

- ^ a b c FAO. 2006. World agriculture: towards 2030/2050. Prospects for food, nutrition, agriculture and major commodity groups. Interim report. Global Perspectives Unit, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. 71 pp.

- ISBN 978-0739136980.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (2017-08-25). "Meat and Dairy Production". Our World in Data.

- ^ a b "Information About Soya, Soybeans". 2011-10-16. Archived from the original on 2011-10-16. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ISSN 0377-8401.

- PMID 1654177.

- ^ a b c Steinfeld, Henning; Gerber, Pierre; Wassenaar, Tom; Castel, Vincent; Rosales, Mauricio; de Haan, Cees (2006), Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options (PDF), Rome: FAO

- ^ a b c d e Mottet, A.; de Haan, C.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G.; Opio, C.; Gerber, P. (2022). More fuel for the food/feed debate. FAO.

- ^ ISSN 2211-9124.

- ISBN 978-3-319-95726-5, retrieved 2023-02-20

- JSTOR 23243036.

- .

- ^ Hoffman, L. and A. Baker. 2010. Market issues and prospects for U.S. distillers' grains supply, use, and price relationships. USDA FDS-10k-01

- ^ National Research Council. 2000. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle. National Academy Press.

- .

- .

- .

- .

- ^ PMID 29853680.

- ^ Merrill, Dave; Leatherby, Lauren (2018-07-31). "Here's How America Uses Its Land". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ "Agricultural land (% of land area) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ "Arable land (% of land area) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ a b c d e Carrington, Damian (20 July 2023). "Vegan diet massively cuts environmental damage, study shows". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ a b "How much does eating meat affect nations' greenhouse gas emissions?". Science News. 5 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ Wang, George C. (April 9, 2017). "Go vegan, save the planet". CNN. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ Liotta, Edoardo (August 23, 2019). "Feeling Sad About the Amazon Fires? Stop Eating Meat". Vice. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ISBN 978-92-5-105571-7. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ISBN 0-8213-5691-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 10, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2008.)

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help - PMID 27092437.

- S2CID 252636900.

- ^ ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ Konikow, L. W. 2013. Groundwater depletion in the United States (1900-2008). United States Geological Survey. Scientific Investigations Report 2013-5079. 63 pp.

- ^ "HA 730-C High Plains aquifer. Ground Water Atlas of the United States. Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ^ a b USDA. 2011. USDA Agricultural Statistics 2011.

- ^ USDA 2010. 2007 Census of agriculture. AC07-SS-1. Farm and ranch irrigation survey (2008). Volume 3, Special Studies. Part 1. (Issued 2009, updated 2010.) 209 pp. + appendices. Tables 1 and 28.

- ^ a b USDA. 2009. 2007 Census of Agriculture. United States Summary and State Data. Vol. 1. Geographic Area Series. Part 51. AC-07-A-51. 639 pp. + appendices. Table 1.

- ^ a b Kenny, J. F. et al. 2009. Estimated use of water in the United States in 2005, US Geological Survey Circular 1344. 52 pp.

- ^ Zering, K. D., T. J. Centner, D. Meyer, G. L. Newton, J. M. Sweeten and S. Woodruff.2012. Water and land issues associated with animal agriculture: a U.S. perspective. CAST Issue Paper No. 50. Council for Agricultural Science and Technology, Ames, Iowa. 24 pp.

- S2CID 211730442.

- ^ Borunda, Alejandra (March 2, 2020). "How beef eaters in cities are draining rivers in the American West". National Geographic. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ S2CID 92222220.

- ^ Fabrique [merken, design & interactie. "Water footprint of crop and animal products: a comparison". waterfootprint.org. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ "Livestock and the Environment". Archived from the original on 2019-01-29. Retrieved 2017-06-07.

- ^ the US Code of Federal Regulations 40 CFR 122.42(e)

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency. Appendix to EPA ICR 1989.06: Supporting Statement for the Information Collection Request for NPDES and ELG Regulatory Revisions for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (Final Rule)

- ^ the US EPA. National Enforcement Initiative: Preventing animal waste from contaminating surface and groundwater. http://www2.epa.gov/enforcement/national-enforcement-initiative-preventing-animal-waste-contaminating-surface-and-ground#progress Archived 2018-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ JSTOR 26167133.

- JSTOR 90007566.

- ^ Berger, Jamie (2022-04-01). "How Black North Carolinians pay the price for the world's cheap bacon". Vox. Retrieved 2023-11-30.

- PMID 15743727.

- ^ Borrell, Brendan (December 3, 2018). "In California's Fertile Valley, a Bumper Crop of Air Pollution". Undark. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- S2CID 22558834.

- PMID 28806469.

- S2CID 15905956.

- PMID 21228696.

- PMID 16818539.

- PMID 23332647.

- PMID 9042635.

- ^ Carrie, Hribar (2010). "Understanding Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations and Their Impact on Communities" (PDF). 2010 National Association of Local Boards of Health – via Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

- S2CID 245204902.

- ^ Cooke, Christina (2017-05-09). "NC GOP Protects Factory Farms' Right to Pollute". Civil Eats. Retrieved 2023-11-30.

- .

- PMID 21803973.

- ^ Erneubare Energien in Deutschland - Rückblick und Stand des Innovationsgeschehens. Bundesministerium fűr Umwelt, Naturschutz u. Reaktorsicherheit. http://www.bmu.de/files/pdfs/allgemin/application/pdf/ibee_gesamt_bf.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ Biogas from manure and waste products - Swedish case studies. SBGF; SGC; Gasföreningen. 119 pp. http://www.iea-biogas.net/_download/public-task37/public-member/Swedish_report_08.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ "U.S. Anaerobic Digester" (PDF). Agf.gov.bc.ca. 2014-06-02. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ^ NRCS. 2007. An analysis of energy production costs from anaerobic digestion systems on U.S. livestock production facilities. US Natural Resources Conservation Service. Tech. Note 1. 33 pp.

- S2CID 233881148.

- ^ Mitigation of Climate Change: Technical Summary (Report). IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. 2022. TS.5.6.2.

- ^ "FAO – News Article: Food systems account for more than one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions". www.fao.org. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- PMID 37117443.

- S2CID 240562878. News article: "Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production, study finds". The Guardian. 13 September 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (2024-03-18). "Food production is responsible for one-quarter of the world's greenhouse gas emissions". Our World in Data.

- S2CID 206664954.

- ^ Gibbens, Sarah (January 16, 2019). "Eating meat has 'dire' consequences for the planet, says report". National Geographic. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ "How plant-based diets not only reduce our carbon footprint, but also increase carbon capture". Leiden University. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- S2CID 245867412.

- S2CID 255638753.

- ^ "Bovine genomics project at Genome Canada". Archived from the original on 2019-08-10. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ "Canada Is Using Genetics to Make Cows Less Gassy". Wired. 2017-06-09. Archived from the original on 2023-05-24.

- doi:10.1071/AR99004.

- ^ The use of direct-fed microbials for mitigation of ruminant methane emissions: a review

- S2CID 89217740.

- doi:10.4141/a03-109.

- ^ Martin, C. et al. 2010. Methane mitigation in ruminants: from microbe to the farm scale. Animal 4 : pp 351-365.

- .

- S2CID 4498983.

- S2CID 42756018.

- ^ Gerber, P. J., H. Steinfeld, B. Henderson, A. Mottet, C. Opio, J. Dijkman, A. Falcucci and G. Tempio. 2013. Tackling climate change through livestock - a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. 115 pp.

- PMID 37993450.

- ^ Fassler, Joe (2024-02-01). "Research Undermines Claims that Soil Carbon Can Offset Livestock Emissions". DeSmog. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- )

- doi:10.1071/EA00102.

- JSTOR 2937150.

- PMID 21238294.

- ^ Environment Canada. 2013. Amended recovery strategy for the Greater Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus urophasianus) in Canada. Species at Risk Act, Recovery Strategy Series. 57 pp.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. "The contributions of livestock species and breeds to ecosystem services" (PDF).

- FAO. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ National Research Council. 1994. Rangeland Health. New Methods to Classify, Inventory and Monitor Rangelands. Nat. Acad. Press. 182 pp.

- ^ US BLM. 2004. Proposed Revisions to Grazing Regulations for the Public Lands. FES 04-39

- ^ NRCS. 2009. Summary report 2007 national resources inventory. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 123 pp.

- S2CID 52234485.

- ^ Garnett, Tara; Godde, Cécile (2017). "Grazed and confused?" (PDF). Food Climate Research Network. p. 64. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

The non-peer-reviewed estimates from the Savory Institute are strikingly higher – and, for all the reasons discussed earlier (Section 3.4.3), unrealistic.

- ^ "Table of Solutions". Project Drawdown. 2020-02-05. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- S2CID 251349023.

- PMID 33402687.

- S2CID 221522148.

- .

- ^ Manley, J. T.; Schuman, G. E.; Reeder, J. D.; Hart, R. H. (1995). "Rangeland soil carbon and nitrogen responses to grazing". J. Soil Water Cons. 50: 294–298.

- .

- ISSN 0008-3984.

- ^ McDonald, J. M. et al. 2009. Manure use for fertilizer and for energy. Report to Congress. USDA, AP-037. 53pp.

- ^ "Livestock Grazing Guidelines for Controlling Noxious weeds in the Western United States" (PDF). University of Nevada. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. "The contributions of livestock species and breeds to ecosystem services" (PDF).

- ^ Launchbaugh, K. (ed.) 2006. Targeted Grazing: a natural approach to vegetation management and landscape enhancement. American Sheep Industry. 199 pp.

- ^ Damian Carrington, "Humans just 0.01% of all life but have destroyed 83% of wild mammals – study", The Guardian, 21 May 2018 (page visited on 19 August 2018).

- PMID 30213888.

- ^ .

- ^ Woodyatt, Amy (May 26, 2020). "Human activity threatens billions of years of evolutionary history, researchers warn". CNN. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ISSN 1862-4057.

- ^ McGrath, Matt (6 May 2019). "Humans 'threaten 1m species with extinction'". BBC. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

Pushing all this forward, though, are increased demands for food from a growing global population and specifically our growing appetite for meat and fish.

- ^ a b Watts, Jonathan (6 May 2019). "Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

Agriculture and fishing are the primary causes of the deterioration. Food production has increased dramatically since the 1970s, which has helped feed a growing global population and generated jobs and economic growth. But this has come at a high cost. The meat industry has a particularly heavy impact. Grazing areas for cattle account for about 25% of the world's ice-free land and more than 18% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

- ^ ISBN 9789251079201.

- ^ Hance, Jeremy (October 20, 2015). "How humans are driving the sixth mass extinction". The Guardian. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- PMID 26231772.

- ^ "Forests". World Resources Institute. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ Suite 800, 10 G. Street NE; Washington; Dc 20002; Fax +1729-7610, USA / Phone +1729-7600 / (2018-05-04). "Tackling Global Challenges". World Resources Institute. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Sutter, John D. (December 12, 2016). "How to stop the sixth mass extinction". CNN. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ Boyle, Louise (February 22, 2022). "US meat industry using 235m pounds of pesticides a year, threatening thousands of at-risk species, study finds". The Independent. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- S2CID 53006161.

- ^ Knowles, C. J. (1986). "Some relationships of black-tailed prairie dogs to livestock grazing". Great Basin Naturalist. 46: 198–203.

- ^ Neel. L.A. 1980. Sage Grouse Response to Grazing Management in Nevada. M.Sc. Thesis. Univ. of Nevada, Reno.

- S2CID 81449626.

- JSTOR 3897382.

- S2CID 55282106.

- ^ Holechek, J. L.; et al. (1982). "Manipulation of grazing to improve or maintain wildlife habitat". Wildlife Soc. Bull. 10: 204–210.

- PMID 35757873.

The dramatic deforestation resulting from land conversion for agriculture and meat production could be reduced via adopting a diet that reduces meat consumption. Less meat can translate not only into less heat, but also more space for biodiversity . . . Although among many Indigenous populations, meat consumption represents a cultural tradition and a source of protein, it is the massive planetary monopoly of industrial meat production that needs to be curbed

- ^ a b Pena-Ortiz, Michelle (2021-07-01). "Linking aquatic biodiversity loss to animal product consumption: A review" (PDF). Freshwater and Marine Biology: 57.

- ^ Belsky, A. J.; et al. (1999). "Survey of livestock influences on stream and riparian ecosystems in the western United States". J. Soil Water Cons. 54: 419–431.

- S2CID 46525184.

- ^ "Pasture, Rangeland, and Grazing Operations - Best Management Practices | Agriculture | US EPA". Epa.gov. 2006-06-28. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ^ "Grazing management processes and strategies for riparian-wetland areas" (PDF). US Bureau of Land Management. 2006. p. 105.

- ISSN 1516-3598.

- ^ a b Key, N. et al. 2011. Trends and developments in hog manure management, 1998-2009. USDA EIB-81. 33 pp.

- ^ S2CID 3685205.

- JSTOR 43748533.

- JSTOR 24861020.

- JSTOR 43707749.

- ^ "Fisheries, Food Security, and Climate Change in the Indo-Pacific Region". Sea Change: 111–121. 2014.

- ^ Bousquet-Melou, Alain; Ferran, Aude; Toutain, Pierre-Louis (May 2010). "Prophylaxis & Metaphylaxis in Veterinary Antimicrobial Therapy". Conference: 5th International Conference on Antimicrobial Agents in Veterinary Medicine (AAVM)At: Tel Aviv, Israel – via ResearchGate.

- ^ British Veterinary Association, London (May 2019). "BVA policy position on the responsible use of antimicrobials in food producing animals" (PDF). Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- S2CID 1312176.

- PMID 16677683.

- ISBN 9780120007851.

- S2CID 206662316.

- ^ ESVAC (European Medicines Agency) (October 2019). "Sales of veterinary antimicrobial agents in 31 European countries in 2017: Trends from 2010 to 2017" (PDF). Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Torrella, Kenny (2023-01-08). "Big Meat just can't quit antibiotics". Vox. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

- S2CID 202699175.

- S2CID 3861749.

- ^ S2CID 4048235.

- PMID 29387833.

- S2CID 39361030.

- ^ European Medicines Agency (4 September 2019). "Implementation of the new Veterinary Medicines Regulation in the EU".

- ^ OECD, Paris (May 2019). "Working Party on Agricultural Policies and Markets: Antibiotic Use and Antibiotic Resistance in Food Producing Animals in China". Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ US Food & Drug Administration (July 2019). "Timeline of FDA Action on Antimicrobial Resistance". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ "WHO guidelines on use of medically important antimicrobials in food-producing animals" (PDF).

- ^ European Commission, Brussels (December 2005). "Ban on antibiotics as growth promoters in animal feed enters into effect".

- ^ "The Judicious Use of Medically Important Antimicrobial Drugs in Food-Producing Animals" (PDF). Guidance for Industry (#209). 2012.

- ^ "Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD) Basics". AVMA. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ University of Nebraska, Lincoln (October 2015). "Veterinary Feed Directive Questions and Answers". UNL Beef. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- S2CID 59196.

- PMID 33005639.

- S2CID 235503730.

- PMID 30140756.

- PMID 33466241.

- ^ S2CID 227242500.

- S2CID 248526001.. Science News. 5 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

News article: "Replacing some meat with microbial protein could help fight climate change" - ^ "Lab-grown meat and insects 'good for planet and health'". BBC News. 25 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- S2CID 257158726. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- S2CID 235595143.

- ^ "Plant-based meat substitutes - products with future potential | Bioökonomie.de". biooekonomie.de. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Berlin, Kustrim CerimiKustrim Cerimi studied biotechnology at the Technical University in; biotechnology, is currently doing his PhD He is interested in the broad field of fungal; Artists, Has Collaborated in Various Interdisciplinary Projects with; Artists, Hybrid (28 January 2022). "Mushroom meat substitutes: A brief patent overview". On Biology. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- S2CID 13755426.

- PMID 26024497.

- ISSN 1080-7446.

- S2CID 219701817.

- PMID 31690027.

- S2CID 227130240.

- PMID 21139125.

- ^ Zelman, Kathleen M.; MPH; RD; LD. "The Truth Behind the Top 10 Dietary Supplements". WebMD. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- PMID 35010904.

- ^ Boston, 677 Huntington Avenue; Ma 02115 +1495‑1000 (2012-09-18). "Vitamin K". The Nutrition Source. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - PMID 35134067.

- S2CID 247307240. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- S2CID 233867757.

- PMID 31515473.

- S2CID 229282344.

- ^ "Have we reached 'peak meat'? Why one country is trying to limit its number of livestock". the Guardian. 2023-01-16. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- S2CID 237101457.

- ^ "A blueprint for scaling voluntary carbon markets | McKinsey". www.mckinsey.com. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ "These are the UK supermarket items with the worst environmental impact". New Scientist. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- PMID 35939701.

- ^ S2CID 248742133.

- ^ S2CID 236963808.

- ^ "Up to 3,000 'peak polluters' given last chance to close by Dutch government". the Guardian. 2022-11-30. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Fortuna, Carolyn (2022-09-08). "Is It Time To Start Banning Ads For Meat Products?". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- ^ "Towards sustainable food consumption – SAPEA". Retrieved 2023-06-29.

- ^ PMID 23732659.

- PMID 10706529.

- PMID 17384781.

- S2CID 4764858.

- S2CID 144569890.

- PMID 19890165.

- ^ Edwards, Bob (January 2001). "Race, poverty, political capacity and the spatial distribution of swine waste in North Carolina, 1982-1997". NC Geogr.

- ^ "FAO's Animal Production and Health Division: Pigs and Environment". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2017-04-23.