Environmental movement in the United States

The organized environmental movement is represented by a wide range of non-governmental organizations or NGOs that seek to address environmental issues in the United States. They operate on local, national, and international scales. Environmental NGOs vary widely in political views and in the ways they seek to influence the environmental policy of the United States and other governments.

The environmental movement today consists of both large national groups and also many smaller local groups with local concerns. Some resemble the old U.S. conservation movement - whose modern expression is

Issues

Scope of the movement

- The early sustainable forestry. Today it includes sustainable yield of natural resources, preservation of wilderness areas and biodiversity.

- The modern Environmental movement, which began in the 1960s with concern about air and water pollution, became broader in scope to include all landscapes and human activities. See List of environmental issues.

- Environmental health movement dating at least to Progressive Era (the 1890s - 1920s) urban reforms including clean water supply, more efficient removal of raw sewage and reduction in crowded and unsanitary living conditions. Today Environmental health is more related to nutrition, preventive medicine, ageing well and other concerns specific to the human body's well-being.

- Gaia theory, value of Earth and other interrelations between human sciences and human responsibilities. Its spinoff deep ecology was more spiritual but often claimed to be science.[citation needed]

- Environmental justice is a movement that began in the U.S. in the 1980s and seeks an end to environmental racism. Often, low-income and minority communities are located close to highways, garbage dumps, and factories, where they are exposed to greater pollution and environmental health risk than the rest of the population. The Environmental Justice movement seeks to link "social" and "ecological" environmental concerns, while at the same time keeping environmentalists conscious of the dynamics in their own movement, i.e. racism, sexism, homophobia, classicism, and other malaises of the dominant culture.[5]

As public awareness and the environmental sciences have improved in recent years, environmental issues have broadened to include key concepts such as "

and biogenetic pollution.Environmental movements often interact or are linked with other social movements, e.g. for peace, human rights, and animal rights; and against nuclear weapons and/or nuclear power, endemic diseases, poverty, hunger, etc.

Some US colleges are now going green by signing the "President's Climate Commitment," a document that a college President can sign to enable said colleges to practice environmentalism by switching to solar power, etc.[6]

| 1971 | 1981 | 1992 | 1997 | 2004 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sierra Club (1892) | 124 | 246 | 615 | 569 | 736 |

National Audubon Society (1905) |

115 | 400 | 600 | 550 | 550 |

| National Parks Conservation Association (1919) | 49 | 27 | 230 | 375 | 375 |

| Izaak Walton League (1922) | 54 | 48 | 51 | 42 | 45 |

| Wilderness Society (1935) | 62 | 52 | 365 | 237 | 225 |

| National Wildlife Federation (1936) | 540 | 818 | 997 | 650 | 650 |

| Defenders of Wildlife (1947) | 13 | 50 | 77 | 215 | 463 |

| The Nature Conservancy (1951) | 22 | 80 | 545 | 865 | 972 |

| WWF-US (1961) | n.a. | n.a. | 970 | 1,200 | 1,200 |

| Environmental Defense Fund (1967) | 20 | 46 | 175 | 300 | 350 |

| Friends of the Earth (US) (1969) | 7 | 25 | 30 | 20 | 35 |

| Natural Resources Defense Council (1970) | 5 | 40 | 170 | 260 | 450 |

| Greenpeace USA (1975) | n.a. | n.a. | 2,225 | 400 | 250 |

History

Early European settlers came to the United States brought from Europe the concept of the commons. In the colonial era, access to natural resources was allocated by individual towns, and disputes over fisheries or land use were resolved at the local level. Changing technologies, however, strained traditional ways of resolving disputes of resource use, and local governments had limited control over powerful special interests. For example, the damming of rivers for mills cut off upriver towns from fisheries; logging and clearing of forest in watersheds harmed local fisheries downstream. In New England, many farmers became uneasy as they noticed clearing of the forest changed stream flows and a decrease in bird population which helped control insects and other pests. These concerns become widely known with the publication of Man and Nature (1864) by George Perkins Marsh. The environmental impact method of analysis is generally the main mode for determining what issues the environmental movement is involved in. This model is used to determine how to proceed in situations that are detrimental to the environment by choosing the way that is least damaging and has the fewest lasting implications.[8]

Conservation movement

Conservation first became a national issue during the

Progressive era

Roosevelt established the

Gifford Pinchot had been appointed by McKinley as chief of Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. In 1905, his department gained control of the national forest reserves. Pinchot promoted private use (for a fee) under federal supervision. In 1907, Roosevelt designated sixteen million acres (65,000 km2) of new national forests just minutes before a deadline.

In May 1908, Roosevelt sponsored the Conference of Governors held in the White House, with a focus on natural resources and their most efficient use. Roosevelt delivered the opening address: "Conservation as a National Duty."

In 1903 Roosevelt toured the Yosemite Valley with

Other influential conservationists of the

New Deal

Post-1945

After World War II increasing encroachment on wilderness land evoked the continued resistance of conservationists, who succeeded in blocking a number of projects in the 1950s and 1960s, including the proposed Bridge Canyon Dam that would have backed up the waters of the Colorado River into the Grand Canyon National Park.

The Inter-American Conference on the Conservation of Renewable Natural Resources met in 1948 as a collection of nearly 200 scientists from all over the Americans forming the trusteeship principle that:

"No generation can exclusively own the renewable resources by which it lives. We hold the commonwealth in trust for prosperity, and to lessen or destroy it is to commit treason against the future"[17]

Beginning of the modern movement

During the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, several events occurred which raised the public awareness of harm to the environment caused by man. In 1954, the 23 man crew of the Japanese fishing vessel Lucky Dragon was exposed to radioactive fallout from a hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll. By 1969, the public reaction to an ecologically catastrophic oil spill from an offshore well in California's Santa Barbara Channel, Barry Commoner's protest against nuclear testing, along with Rachel Carson's 1962 book Silent Spring,[18] and Paul R. Ehrlich's The Population Bomb (1968)[19] all added anxiety about the environment. Pictures of Earth from space emphasized that the earth was small and fragile.[20]

As the public became more aware of environmental issues, concern about air pollution, water pollution, solid waste disposal, dwindling energy resources, radiation, pesticide poisoning (particularly use of DDT as described in Carson's influential Silent Spring),[21] noise pollution, and other environmental problems engaged a broadening number of sympathizers. That public support for environmental concerns was widespread became clear in the Earth Day demonstrations of 1970.[22]

Several books after the middle of the 20th century contributed to the rise of American environmentalism (as distinct from the longer-established conservation movement), especially among college and university students and the more literate public. One was the publication of the first textbook on

During his time as U.S President,

Wilderness preservation

In the modern wilderness preservation movement, important philosophical roles are played by the writings of John Muir who had been activist in the late 19th and early 20th century. Along with Muir perhaps most influential in the modern movement is Henry David Thoreau who published Walden in 1854. Also important was forester and ecologist Aldo Leopold, one of the founders of the Wilderness Society in 1935, who wrote a classic of nature observation and ethical philosophy, A Sand County Almanac, (1949).[26][27]

There is also a growing movement of campers and other people who enjoy outdoor recreation activities to help preserve the environment while spending time in the wilderness.[28]

Anti-nuclear movement

The anti-nuclear movement in the United States consists of more than 80

More recent campaigning by anti-nuclear groups has related to several nuclear power plants including the

Some scientists and engineers have expressed reservations about nuclear power, including:

Antitoxics groups

Antitoxics groups are a subgroup that is affiliated with the Environmental Movement in the United States, that is primarily concerned with the effects that cities and their by-products have on humans. This aspect of the movement is a self-proclaimed "movement of housewives".[8] Concern around the issues of groundwater contamination and air pollution rose in the early 1980s and individuals involved in antitoxics groups claim that they are concerned for the health of their families.[8] A prominent case can be seen in the Love Canal Homeowner's association (LCHA); in this case, a housing development was built on a site that had been used for toxic dumping by the Hooker Chemical Company. As a result of this dumping, the residents had symptoms of skin irritation, Lois Gibbs, a resident of the development, started a grassroots campaign for reparations. Eventual success led to the government having to purchase homes that were sold in the development.[8]

Federal legislation in the 1970s

Prior to the 1970s the protection of basic air and water supplies was a matter mainly left to each state. During the 1970s, the primary responsibility for clean air and water shifted to the federal government. Growing concerns, both environmental and economic, from cities and towns as well as sportsman and other local groups, and senators such as Maine's

The creation of these laws led to a major shift in the environmental movement. Groups such as the Sierra Club shifted focus from local issues to becoming a lobby in Washington and new groups, for example, the Natural Resources Defense Council and Environmental Defense, arose to influence politics as well. (Larson)[51]

Renewed focus on local action

In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan sought to curtail the scope of environmental protection taking steps such as appointing James G. Watt. The major environmental groups responded with mass mailings which led to increased membership and donations.

When industry groups lobbied to weaken regulation and a backlash against environmental regulations, the so-called wise use movement gained importance and influence.(Larson)[citation needed]

"Post-environmentalism"

In 2004, with the environmental movement seemingly stalled, some environmentalists started questioning whether "environmentalism" was even a useful political framework. According to a controversial essay titled "The Death of Environmentalism " (Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus, 2004) American environmentalism has been remarkably successful in protecting the air, water, and large stretches of wilderness in North America and Europe, but these environmentalists have stagnated as a vital force for cultural and political change.

Shellenberger and Nordhaus wrote, "Today environmentalism is just another special interest. Evidence for this can be found in its concepts, its proposals, and its reasoning. What stands out is how arbitrary environmental leaders are about what gets counted and what doesn't as 'environmental.' Most of the movement's leading thinkers, funders, and advocates do not question their most basic assumptions about who we are, what we stand for, and what it is that we should be doing." Their essay was followed by a speech in San Francisco called "Is Environmentalism Dead?" by former Sierra Club President, Adam Werbach, who argued for the evolution of environmentalism into a more expansive, relevant and powerful progressive politics. Werbach endorsed building an environmental movement that is more relevant to average Americans and controversially chose to lead Wal-Mart's effort to take sustainability mainstream.

These "post-environmental movement" thinkers argue that the ecological crises the human species faces in the 21st century are qualitatively different from the problems the environmental movement was created to address in the 1960s and 1970s. They argue that climate change and habitat destruction are global and more complex, therefore demanding far deeper transformations of the economy, the culture and political life. The consequence of environmentalism's outdated and arbitrary definition, they argue, is a political irrelevancy.

These "politically neutral" groups tend to avoid global conflicts and view the settlement of inter-human conflict as separate from regard for nature – in direct contradiction to the ecology movement and peace movement which have increasingly close links: while Green Parties, Greenpeace, and groups like the ACTivist Magazine regard ecology, biodiversity, and an end to non-human extinction as an absolute basis for peace, the local groups may not, and see a high degree of global competition and conflict as justifiable if it lets them preserve their own local uniqueness. However, such groups tend not to "burn out" and to sustain for long periods, even generations, protecting the same local treasures.

Local groups increasingly find that they benefit from collaboration, e.g. on consensus decision-making methods, or making

Groups such as The Bioregional Revolution are calling on the need to bridge these differences, as the converging problems of the 21st century they claim compel the people to unite and to take decisive action. They promote

Environmental rights

Many environmental lawsuits turn on the question of who has standing; are the legal issues limited to property owners, or does the general public have a right to intervene? Christopher D. Stone's 1972 essay, "Should trees have standing?" seriously addressed the question of whether natural objects themselves should have

One of the earliest lawsuits to establish that citizens may sue for environmental and aesthetic harms was Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v. Federal Power Commission, decided in 1965 by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. The case helped halt the construction of a power plant on Storm King Mountain in New York State. See also United States environmental law and David Sive, an attorney who was involved in the case.

Conservation biology is an important and rapidly developing field. One way to avoid the stigma of an "ism" was to evolve early anti-nuclear groups into the more scientific Green Parties, sprout new NGOs such as Greenpeace and Earth Action, and devoted groups to protecting global biodiversity and preventing global warming and climate change. But in the process, much of the emotional appeal, and many of the original aesthetic goals were lost. Nonetheless, these groups have well-defined ethical and political views, backed by science.[52]

Criticisms

Some people are

Novelist

A consistent theme acknowledged by both supporters and critics (though more commonly vocalized by critics) of the environmental movement is that we know very little about the Earth we live in. Most fields of environmental studies are relatively new, and therefore what research we have is limited and does not date far enough back for us to completely understand long-term environmental trends. This has led a number of environmentalists to support the use of the precautionary principle in policy-making, which ultimately asserts that we don't know how certain actions may affect the environment and because there is reason to believe they may cause more harm than good we should refrain from such actions.[56]

Elitist

In the December 1994 Wild Forest Review, Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St. Clair wrote "The mainstream environmental movement was elitist, highly paid, detached from the people, indifferent to the working class, and a firm ally of big government.…The environmental movement is now accurately perceived as just another well-financed and cynical special interest group, its rancid infrastructure supported by Democratic Party operatives and millions in grants from corporate foundations."

Within many Environmental organizations there is a lack of diversity, including often white women as the main demographic . Hare explains how ""major "environmental problems of the environmental movement were fundamentally different for black and White people."[57] For the middle class white population in the US throughout history, environmental issues have often included pollution, barriers to recreational activities, etc. On the other hand, for people of color issues of the environmental movement were life or death including issues of "smoke, soot, dust, . . . fumes gases, stench, and carbon monoxide."[57] The issues themselves faced by different populations, causes different focuses for environmental organizations depending on whose in charge. Often if a minority who has experienced life-threatening environmental issues and is put in a position of power within an environmental organization, the focus will shift more towards focus on these "major" issues. For instance, in the past environmental organizations have focused "on preserving natural resources and endangered species instead of protecting people of color from hazardous waste sites being built in their communities". In a crucial 2014, State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations study, found that the percentage of minorities working for environmental organizations has never exceeded 16% and less than 12% have achieved positions of leadership.[58]

Wilderness myth

Historians have criticized the modern environmental movement for having romantic idealizations of wilderness.[59] William Cronon writes "wilderness serves as the unexamined foundation on which so many of the quasi-religious values of modern environmentalism rest." Cronon claims that "to the extent that we live in an urban-industrial civilization but at the same time pretend to ourselves that our real home is in the wilderness, to just that extent we give ourselves permission to evade responsibility for the lives we actually lead."[60]

Similarly Michael Pollan has argued that the wilderness ethic leads people to dismiss areas whose wildness is less than absolute. In his book Second Nature, Pollan writes that "once a landscape is no longer 'virgin' it is typically written off as fallen, lost to nature, irredeemable."[61]

Debates within the movement

Within the environmental movement, an ideological debate has taken place between those with an

While the ecocentric view focused on biodiversity and wilderness protection the anthropocentric view focuses on urban pollution and social justice. Some environmental writers, for example,

Environmentalism and politics

Environmentalists gained popularity in American politics after the creation or strengthening of numerous US environmental laws, including the

Fewer environmental laws have been passed in the last decade as corporations and other

Much environmental activism is directed towards

As human population and industrial activity continue to increase, environmentalists often find themselves in serious conflict with those who believe that human and industrial activities should not be overly regulated or restricted, such as some libertarians.

Environmentalists often clash with others, particularly corporate interests, over issues of the management of

Radical environmentalism

While most environmentalists are often mainstream and peaceful, other groups are more radical in their approach. Adherents of

Clashes by police

In 2023, for the first time in the history of the United States, the police killed an environmental activist during a protest.[68] The protesters were camping in Atlanta's South River Forest, a natural area that the City of Atlanta and Police planned to raze in order to erect a police training facility to be called "Cop City." Police attacked protesters on 18 January 2023. One protester, Tortuguita or, Manuel Esteban Páez Terán was killed and seven more were arrested.[68]

See also

- History of the environmental movement in the United States

- Earth Days, a 2009 documentary feature film about the start of the environmental movement in the United States.

- Environmentalism (Critique of George W. Bush's politics)

- Environmental issues in the United States

- Environmental racism

- List of American non-fiction environmental writers

- List of anti-nuclear protests in the United States

- Metal roof

- Sex ecology

References

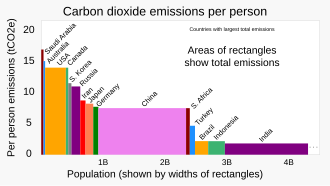

- ^ ● "Territorial (MtCO2)". GlobalCarbonAtlas.org. Retrieved December 30, 2021. (choose "Chart view"; use download link)

● Data for 2020 is also presented in Popovich, Nadja; Plumer, Brad (November 12, 2021). "Who Has The Most Historical Responsibility for Climate Change?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 29, 2021.

● Source for country populations: "List of the populations of the world's countries, dependencies, and territories". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. - ^ EPA, OA, US (January 12, 2016). "Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data | US EPA". US EPA. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ "United States: Climate Policy". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ McGrath, Matt (October 20, 2020). "US election 2020: What the results will mean for climate change". BBC. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- )

- ^ "Homepage - Second Nature". Second Nature. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ Bosso (2005:54; Bosso and Guber 2006:89), as adapted by Carter (2007:145).

- ^ a b c d e "The American Environmental Movement: Surviving Through Diversity". Archived from the original on December 12, 2009. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ^ "Documents from the February 9, 1888 meeting of the Boone and Crockett Club :: Boone and Crockett Club Records". cdm16013.contentdm.oclc.org. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ Douglas Brinkley, The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (2009) ch 15-26

- ^ W. Todd Benson, President Theodore Roosevelt's Conservations Legacy (2003)

- ^ Gifford Pinchot, Breaking New Ground, (1947) p. 32.

- ^ Robert W. Righter, The Battle over Hetch Hetchy: America's Most Controversial Dam and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism (2005)

- ^ T.H. Watkins, Righteous Pilgrim: The Life and Times of Harold L. Ickes, 1874-1952 (1990)

- ^ David B. Woolner and Henry L. Henderson, eds. FDR and the Environment (2009)

- ^ Neil M. Maher, Nature's New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement (2007)

- ^ New York Times, September 18, 1948 in Fairchild, W.B. (1949) "Renewable Resources: A World Dilemma: Recent Publications on Conservation", Geographical Review 39 (1) pp. 86 - 98

- ISBN 978-0-618-24906-0. Silent Spring initially appeared serialized in three parts in the June 16, June 23, and June 30, 1962 issues of The New Yorkermagazine.

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R. (1968). The Population Bomb. Ballantine Books.

- ISBN 978-0-7565-4732-5.

- ^ Cristóbal S. Berry-Cabán, "DDT and Silent Spring: Fifty years after." Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health 19 (2011): 19-24 online.

- ^ "The History of Earth Day". Earth Day Network. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ Odum, E.P. (1959). "Oikos". Oikos. 10: 1 – via JSTOR.

- S2CID 157339090.

- ^ "Lyndon B. Johnson and the Environment" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ J. Baird Callicott and Michael P. Nelson, eds. The Great New Wilderness Debate: An Expansive Collection of Writings Defining Wilderness from John Muir to Gary Snyder (1998)

- ^ J. Baird Callicott and Robert Frodeman, eds. Encyclopedia of Environmental Ethics and Philosophy (Macmillan Reference USA, 2008)

- ^ "13 Ways to Minimize the Impacts of Camping & Other Outdoor Activities - True North Athletics". Truenorthathletics.com. November 14, 2015. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7425-1827-8.

- ^ Jerry Brown and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age, p. 198.

- ^ Herbert P. Kitschelt. Political Opportunity and Political Protest: Anti-Nuclear Movements in Four Democracies British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 16, No. 1, 1986, p. 62.

- ^ Jonathan Schell. The Spirit of June 12 Archived December 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine The Nation, July 2, 2007.

- ^ 1982 - a million people march in New York City Archived June 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-0-88738-875-0.

- ^ 1,400 Anti-nuclear protesters arrested Miami Herald, June 21, 1983.

- ^ Robert Lindsey. 438 Protesters are Arrested at Nevada Nuclear Test Site New York Times, February 6, 1987.

- ^ 493 Arrested at Nevada Nuclear Test Site New York Times, April 20, 1992.

- ^ "Groups petition against new nuclear plant - MonroeNews.com". Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved July 14, 2010.

- ^ Fermi 3 opposition takes legal action to block new nuclear reactor Archived March 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Oyster Creek's time is up, residents tell board Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Greater Media Examiner, June 28, 2007.

- ^ "PilgrimWatch - Pilgrim Nuclear Watchdog". Pilgrimwatch.org. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ "Unplug Salem Home Page, Nuclear Power Dangers South Jersey". Unplugsalem.org. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-520-24683-6.

- ^ "Stop the Bombs » Blog Archive » Join us at the April 2010 Action Event to Stop the Bombs". Stopthebombs.org. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ "About KYNF". November 22, 2009. Archived from the original on November 22, 2009. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ "Nuclear Waste Task Force - Low-Level Radioactive Waste - Sierra Club". March 8, 2005. Archived from the original on March 8, 2005. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ 22 Arrested in Nuclear Protest The New York Times, August 10, 1989.

- ^ Hundreds Protest at Livermore Lab Archived January 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine The TriValley Herald, August 11, 2003.

- ^ Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety (undated). About CCNS

- ISBN 978-0-16-043625-3.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 9781933782560.

- ^ Julie Doyle, "Climate action and environmental activism: The role of environmental NGOs and grassroots movements in the global politics of climate change." in Climate change and the media (Peter Lang, 2009) pp. 103-116.

- S2CID 145807157.

- ^ ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Crichton, Michael (September 28, 2005). "Full Committee Hearing The Role of Science in Environmental Policy-Making". U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Don Mayer, "The Precautionary Principle and International Efforts to Ban DDT." South Carolina Environmental Law Journal (2000): 135+.

- ^ a b Walter, Haley (2022). "Examining the relationship between environmental justice and the lack of diversity in environmental organizations". Richmond Public Interest Law Review: 219–240.

- .

- ^ Marvin Henberg, "Wilderness, myth, and American character." The George Wright Forum Vol. 11. No. 4. (1994) online.

- ^ William Cronon, Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature (1996) p. 80.

- ^ Michael Pollan, Second Nature: A Gardener’s Education (2003) p. 188

- S2CID 147180080– via Jstor.

- ^ Christmann, Petra (2004). "Multinational Companies and the Natural Environment: Determinants of Global Environmental Policy Standardization". The Academy of Management Journal. 47: 1 – via JSTOR.

- S2CID 17725502.

- ^ Perez, Alejandro Colsa, Bernadette Grafton, Paul Mohai, Rebecca Hardin, Katy Hintzen, and Sara Orvis. "Evolution of the environmental justice movement: activism, formalization and differentiation." Environmental Research Letters 10, no. 10 (2015): 105002.

- ISSN 0954-6553.

- S2CID 7845712.

- ^ a b "Environmental protests have a long history in the US Police had never killed an activist - until now". nbcnews.

Further reading

- Bosso, Christopher. Environment, Inc.: From Grassroots to Beltway. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2005

- Bosso, Christopher, and Deborah Guber. "Maintaining Presence: Environmental Advocacy and the Permanent Campaign." pp. 78–99 in Environmental Policy: New Directions for the Twenty First Century, 6th ed., eds. Norman Vig and Michael Kraft. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2006

- Brinkley, Douglas. Silent Spring Revolution: John F. Kennedy, Rachel Carson, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, and the Great Environmental Awakening (2022) excerpt

- Brinkley, Douglas. The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (2009)

- Carter, Neil. The Politics of the Environment: Ideas, Activism, Policy, 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007

- Davies, Kate. (2013). The Rise of the U.S. Environmental Health Movement. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield

- Daynes, Byron W. and Glen Sussman, White House Politics and the Environment: Franklin D. Roosevelt to George W. Bush (2010) .

- De Steiguer, Joseph Edward (2006). The Origins of Modern Environmental Thought. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-2461-7.

- Fox, Stephen R. (1981). John Muir and his legacy: the American conservation movement. Little Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-29110-1.

- Gottlieb, Robert (1993). Forcing the spring: the transformation of the American environmental movement. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-123-6.

- Hays, Samuel P. Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency (Harvard University Press, 1959).

- Hays, Samuel P. Beauty, Health, and Permanence: Environmental Politics in the United States, 1955-1985 (1989)

- Hays, Samuel P. 'A History of Environmental Politics Since 1945 (2000), abridged version

- Huffman, James L. “A History of Forest Policy in the United States.” Environmental Law 8#2 (1978): 239-280.

- Judd, Richard W. Common Lands and Common People: The Origins of Conservation in Northern New England (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997).

- Kline, Benjamin. First Along the River: A brief history of the U.S. environmental movement (4th ed. 2011)

- Nash, Roderick (1982). Wilderness and the American Mind, Third Edition. ISBN 978-0-300-02910-9.

- Reiger, John F. American Sportsmen and the Origins of Conservation (2000)

- Shabecoff, Philip (2003). A Fierce Green Fire: The American Environmental Movement. Island Press. ISBN 978-1-55963-437-3.

- Spears, Ellen Griffith. Rethinking the American Environmental Movement Post-1945 (Routledge, 2019).

- Strong, Douglas Hillman (1988). Dreamers & Defenders: American Conservationists. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9156-0.

- Tresner, Erin. 2009. "Factors Affecting States' Ranking on the 2007 Forbes List of America's Greenest States" (Applied Research Project, Texas State University. online)

External links

- The Emerging Environmental Majority by Christina Larson

- The Illusion of Preservation. Harvard Forestry

- State of Denial

- The Unlikely Environmentalists

- Worldchanging - Leading online magazine about environmental sustainability

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Environment

- Essays on environmental teachings of major religions

- The State of the Environmental Movement Thoreau Institute

- History of the environmental movement - Jeremiah Hall

- A Fierce Green Fire: The Battle for a Living Planet - Documentary film directed and written by Mark Kitchell. Explores 50 years of environmental activism in the USA. Inspired by the book of the same name by Philip Shabecoff.