Ephrem the Syrian

| Patronage | Spiritual directors and spiritual leaders |

|---|---|

| Part of Oriental Orthodoxy |

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

Ephrem the Syrian

Ephrem is venerated as a

Ephrem wrote a wide variety of hymns, poems, and sermons in verse, as well as prose

Life

Ephrem was born around the year 306 in the city of

In 337, Emperor

One important physical link to Ephrem's lifetime is the

Ephrem, with the others, went first to Amida (

Language

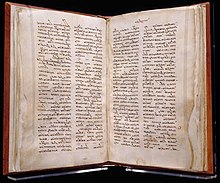

Ephrem wrote exclusively in his native

In the early stages of modern scholarly studies, it was believed that some examples of the long-standing Greek practice of labeling Aramaic as "Syriac", that are found in the

One of the early admirers of Ephrem's works, theologian

Some of those problems persisted up to the recent times, even in scholarly literature, as a consequence of several methodological problems within the field of

Several translations of his writings exist in

Writings

Over four hundred hymns composed by Ephrem still exist. Granted that some have been lost, Ephrem's productivity is not in doubt. The church historian Sozomen credits Ephrem with having written over three million lines. Ephrem combines in his writing a threefold heritage: he draws on the models and methods of early Rabbinic Judaism, he engages skillfully with Greek science and philosophy, and he delights in the Mesopotamian/Persian tradition of mystery symbolism.

The most important of his works are his lyric, teaching hymns (ܡܕܖ̈ܫܐ, madrāšê). These hymns are full of rich, poetic imagery drawn from biblical sources, folk tradition, and other religions and philosophies. The madrāšê are written in stanzas of syllabic verse and employ over fifty different metrical schemes. The form is defined by an antiphon, or congregational refrain (ܥܘܢܝܬܐ, ‘ûnîṯâ), between each independent strophe (or verse), and the refrain's melody mimics that of the opening half of the strophe.[47] Each madrāšâ had its qālâ (ܩܠܐ), a traditional tune identified by its opening line. All of these qālê are now lost. It seems that Bardaisan and Mani composed madrāšê, and Ephrem felt that the medium was a suitable tool to use against their claims. The madrāšê are gathered into various hymn cycles. Each group has a title — Carmina Nisibena, On Faith, On Paradise, On Virginity, Against Heresies — but some of these titles do not do justice to the entirety of the collection (for instance, only the first half of the Carmina Nisibena is about Nisibis). Some of these hymn cycles provide implicit insight into Ephrem's perceived level of comfort with incorporating feminine imagery into his writings. One such hymn cycle was Hymns on the Nativity, centered around Mary, which contained 28 hymns and had the clearest pervasive theme of Ephrem's hymn cycles.[47] An example of feminine imagery is found when Ephrem writes of the baby Jesus: "he was lofty but he sucked Mary's milk and from his blessings all creation sucks."[47]

Particularly influential were his Hymns Against Heresies.[48] Ephrem used these to warn his flock of the heresies that threatened to divide the early church. He lamented that the faithful were "tossed to and fro and carried around with every wind of doctrine, by the cunning of men, by their craftiness and deceitful wiles" (Eph 4:14).[49] He devised hymns laden with doctrinal details to inoculate right-thinking Christians against heresies such as docetism. The Hymns Against Heresies employ colourful metaphors to describe the Incarnation of Christ as fully human and divine. Ephrem asserts that Christ's unity of humanity and divinity represents peace, perfection and salvation; in contrast, docetism and other heresies sought to divide or reduce Christ's nature and, in doing so, rend and devalue Christ's followers with their false teachings.

Performance Practices and Gender

The relationship between Ephrem's compositions and femininity is shown again in documentation suggesting that the madrāšê were sung by all-women choirs with an accompanying lyre. These women's choirs were composed of members of the Daughters of the Covenant, an important institution in historical Syriac Christianity, but they weren't always labeled as such.[50] Ephrem, like many Syriac liturgical poets, believed that women's voices were important to hear in the church as they were modeled after Mary, mother of Jesus, whose acceptance of God's call led to salvation for all through the birth of Jesus.[51] One variety of the madrāšê, the soghyatha, was sung in a conversational style between male and female choirs.[51] The women's choir would sing the role of biblical women, and the men's choir would sing the male role. Through the role of singing Ephrem's madrāšê, women's choirs were granted a role in worship.[50]

Further writings

Ephrem also wrote verse homilies (ܡܐܡܖ̈ܐ, mêmrê). These sermons in poetry are far fewer in number than the madrāšê. The mêmrê were written in a heptosyllabic couplets (pairs of lines of seven syllables each).

The third category of Ephrem's writings is his prose work. He wrote a biblical commentary on the

He also wrote refutations against Bardaisan, Mani, Marcion and others.[52][53]

Syriac churches still use many of Ephrem's hymns as part of the annual cycle of worship. However, most of these liturgical hymns are edited and conflated versions of the originals.

The most complete, critical text of authentic Ephrem was compiled between 1955 and 1979 by Dom Edmund Beck, OSB, as part of the Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium.

Ephrem is attributed with writing hagiographies such as The Life of Saint Mary the Harlot, though this credit is called into question.[54]

One of the works attributed to Ephrem was the Cave of Treasures, written by a much later but unknown author, who lived at the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th century.[55]

Symbols and metaphors

Ephrem's writings contain a rich variety of symbols and metaphors. Christopher Buck gives a summary of analysis of a selection of six key scenarios (the way, robe of glory,

Greek Ephrem

Ephrem's meditations on the symbols of Christian faith and his stand against heresy made him a popular source of inspiration throughout the church. There is a huge corpus of Ephrem pseudepigraphy and legendary hagiography in many languages. Some of these compositions are in verse, often mimicking Ephrem's heptasyllabic couplets.

There is a very large number of works by "Ephrem" extant in Greek. In the literature this material is often referred to as "Greek Ephrem", or Ephraem Graecus (as opposed to the real Ephrem the Syrian), as if it was by a single author. This is not the case, but the term is used for convenience. Some texts are in fact Greek translations of genuine works by Ephrem. Most are not. The best known of these writings is the Prayer of Saint Ephrem, which is recited at every service during Great Lent and other fasting periods in Eastern Christianity.

There are also works by "Ephrem" in

There has been very little critical examination of any of these works. They were edited uncritically by Assemani, and there is also a modern Greek edition by Phrantzolas.[57]

Veneration as a saint

Soon after Ephrem's death, legendary accounts of his life began to circulate. One of the earlier "modifications" is the statement that Ephrem's father was a pagan priest of Abnil or Abizal. However, internal evidence from his authentic writings suggest that he was raised by Christian parents.[58]

Ephrem is venerated as an example of monastic discipline in

On 5 October 1920, Pope

The most popular title for Ephrem is Harp of the Spirit (Syriac: ܟܢܪܐ ܕܪܘܚܐ, Kenārâ d-Rûḥâ). He is also referred to as the Deacon of Edessa, the Sun of the Syrians and a Pillar of the Church.[61]

His Roman Catholic feast day of 9 June conforms to his date of death. For 48 years (1920–1969), it was on 18 June, and this date is still observed in the Extraordinary Form.[62]

Ephrem is honored with a

Ephrem is

Translations

- Sancti Patris Nostri Ephraem Syri opera omnia quae exstant (3 vol), by Peter Ambarach Rome, 1737–1743.

- Ephrem the Syrian Hymns, introduced by John Meyendorff, translated by Kathleen E. McVey. (New York: Paulist Press, 1989) ISBN 0-8091-3093-9

- St. Ephrem Hymns on Paradise, translated by Sebastian Brock (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1990). ISBN 0-88141-076-4

- Saint Ephrem's Commentary on Tatian's Diatessaron: An English Translation of Chester Beatty Syriac MS 709 with Introduction and Notes, translated by Carmel McCarthy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).

- St. Ephrem the Syrian Commentary on Genesis, Commentary on Exodus, Homily on our Lord, Letter to Publius, translated by Edward G. Mathews Jr., and Joseph P. Amar. Ed. by Kathleen McVey. (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1994). ISBN 978-0-8132-1421-4

- St. Ephrem the Syrian The Hymns on Faith, translated by Jeffrey Wickes. (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2015). ISBN 978-0-8132-2735-1

- San Efrén de Nísibis Himnos de Navidad y Epifanía, by Efrem Yildiz Sadak Madrid, 2016 (in Spanish). ISBN 978-84-285-5235-6

- Saint Ephraim the Syrian Eschatological Hymns and Homilies, translated by M.F. Toal and Henry Burgess, amended. (Florence, AZ: SAGOM Press, 2019). ISBN 978-1-9456-9907-8

See also

Notes

- Amharic: ቅዱስ ኤፍሬም ሶርያዊ

References

- ^ Brock 1992a.

- ^ Brock 1999a.

- ^ Parry 1999, p. 180.

- ^ Karim 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Possekel 1999, p. 1.

- ^ Lipiński 2000, p. 11.

- ^ Russell 2005, p. 179-235.

- ^ a b Brock 1992a, p. 16.

- ^ McVey 1989, p. 5.

- ^ Russell 2005, p. 220-222.

- ^ Parry 1999, p. 180-181.

- ^ Russell 2005, p. 215, 217, 223.

- ^ "Saint Ephrem". 9 June 2022. p. Franciscan Media. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Venerable Ephraim the Syrian". p. The Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Harp of the Holy Spirit: St. Ephrem, Deacon and Doctor of the Church". p. The Divine Mercy. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ Russell 2005, p. 195-196.

- ^ Healey 2007, p. 115–127.

- ^ Brock 1999a, p. 105.

- ^ Griffith 2002, p. 15, 20.

- ^ Palmer 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Griffith 2006, p. 447.

- ^ Debié 2009, p. 103.

- ^ Messo 2011, p. 119.

- ^ Simmons 1959, p. 13.

- ^ Toepel 2013, p. 540-584.

- ^ Wood 2007, p. 131-140.

- ^ Rubin 1998, p. 322-323.

- ^ Toepel 2013, p. 531-539.

- ^ Minov 2013, p. 157-165.

- ^ Ruzer 2014, p. 196-197.

- ^ Brock 1992c, p. 226.

- ^ Rompay 2000, p. 78.

- ^ Butts 2011, p. 390-391.

- ^ Butts 2019, p. 222.

- ^ Amar 1995, p. 64-65.

- ^ Brock 1999b, p. 14-15.

- ^ Azéma 1965, p. 190-191.

- ^ Amar 1995, p. 64.

- ^ Amar 1995, p. 65.

- ^ Amar 1995, p. 21.

- ^ Brock 1999b, p. 15.

- ^ Rompay 2004, p. 99.

- ^ Minov 2020, p. 304.

- ^ Wood 2012, p. 186.

- ^ Minov 2013, p. 160.

- ^ "Sergey Minov, Cult of Saints, E02531".

- ^ JSTOR 42612097– via JSTOR.

- ^ Griffith 1999, p. 97-114.

- ^ Mourachian 2007, p. 30-31.

- ^ a b Ashbrook Harvey, Susan (June 28, 2018). "Revisiting the Daughters of the Covenant: Women's Choirs and Sacred Song in Ancient Syriac Christianity". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 8 (2).

- ^ a b Ashbrook Harvey, Susan (2010). "Singing women's stories in Syriac tradition". Internationale kirchliche Zeitschrift. 100 (3): 171–183.

- ^ Mitchell 1912.

- ^ Mitchell, Bevan & Burkitt 1921.

- ^ Brock & Harvey 1998.

- ^ Toepel 2013, p. 531-584.

- ^ Buck 1999, p. 77–109.

- ^ A list of works with links to the Greek text can be found online here.

- ^ "Venerable Ephraim the Syrian". www.oca.org. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ "ЕФРЕМ СИРИН". www.pravenc.ru. Retrieved 2022-08-17.

- ^ PRINCIPI APOSTOLORUM PETRO at Vatican.va

- ^ New Advent at newadvent.org

- ^ "Ephrem". santosepulcro.co.il. Retrieved 2021-10-13.

- ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

Sources

- Amar, Joseph Phillip (1995). "A Metrical Homily on Holy Mar Ephrem by Mar Jacob of Sarug: Critical Edition of the Syriac Text, Translation and Introduction". Patrologia Orientalis. 47 (1): 1–76.

- Azéma, Yvan, ed. (1965). Théodoret de Cyr: Correspondance. Vol. 3. Paris: Editions du Cerf.

- Biesen, Kees den (2006). Simple and bold : Ephrem's art of symbolic thought (1. Gorgias Press ed.). Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-397-8.

- Bou Mansour, Tanios (1988). La pensée symbolique de saint Ephrem le Syrien. Kaslik, Lebanon: Bibliothèque de l'Université Saint Esprit XVI.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1989). "Three Thousand Years of Aramaic Literature". ARAM Periodical. 1 (1): 11–23.

- ISBN 9780879075248.

- ISBN 9780860783053.

- ISBN 0814323618.

- ISBN 9789068318685.

- ISBN 9780860788003.

- S2CID 212688898.

- .

- ISBN 9780881412482.

- ISBN 9780521460835.

- ISBN 9789939850306.

- ISBN 9780520213661.

- Buck, Christopher G. (1999). Paradise and Paradigm: Key Symbols in Persian Christianity and the Baha'i Faith (PDF). New York: State University of New York Press.

- Butts, Aaron M. (2011). "Syriac Language". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 390–391.

- Butts, Aaron M. (2019). "The Classical Syriac Language". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 222–242.

- Debié, Muriel (2009). "Syriac Historiography and Identity Formation". Church History and Religious Culture. 89 (1–3): 93–114. .

- ISBN 9780813205960.

- JSTOR 1583993.

- S2CID 151782759.

- ISBN 9780874625776.

- S2CID 212688360.

- ISBN 0472109979.

- S2CID 166480216. Archived from the originalon 2018-12-11. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- .

- ISBN 9780823287024.

- Hansbury, Mary (trans.) (2006). Hymns of St. Ephrem the Syrian (1. ed.). Oxford: SLG Press.

- Healey, John F. (2007). "The Edessan Milieu and the Birth of Syriac" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 10 (2): 115–127.

- ISBN 9781593332303.

- ASIN B001OIJ75Q.

- ISBN 9789042908598.

- McVey, Kathleen E., ed. (1989). Ephrem the Syrian: Hymns. New York: Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809130931.

- Messo, Johny (2011). "The Origin of the Terms Syria(n) and Suryoyo: Once Again". Parole de l'Orient. 36: 111–125.

- .

- Minov, Sergey (2013). "The Cave of Treasures and the Formation of Syriac Christian Identity in Late Antique Mesopotamia: Between Tradition and Innovation". Between Personal and Institutional Religion: Self, Doctrine, and Practice in Late Antique Eastern Christianity. Brepols: Turnhout. pp. 155–194.

- Minov, Sergey (2020). Memory and Identity in the Syriac Cave of Treasures: Rewriting the Bible in Sasanian Iran. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004445512.

- Mourachian, Mark (2007). "Hymns Against Heresies: Comments on St. Ephrem the Syrian". Sophia. 37 (2).

- Mitchell, Charles W., ed. (1912). S. Ephraim's Prose Refutations of Mani, Marcion, and Bardaisan. Vol. 1. London: Text and Translation Society.

- Mitchell, Charles W.; Bevan, Anthony A.; Burkitt, Francis C., eds. (1921). S. Ephraim's Prose Refutations of Mani, Marcion, and Bardaisan. Vol. 2. London: Text and Translation Society.

- Palmer, Andrew N. (2003). "Paradise Restored". Oriens Christianus. 87: 1–46.

- Parry, Ken, ed. (1999). The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405166584.

- Possekel, Ute (1999). Evidence of Greek Philosophical Concepts in the Writings of Ephrem the Syrian. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042907591.

- Rompay, Lucas van (2000). "Past and Present Perceptions of Syriac Literary Tradition" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 3 (1): 71–103. S2CID 212688244.

- Rompay, Lucas van (2004). "Mallpânâ dilan Suryâyâ Ephrem in the Works of Philoxenus of Mabbog: Respect and Distance" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 7 (1): 83–105. S2CID 212688667.

- Rubin, Milka (1998). "The Language of Creation or the Primordial Language: A Case of Cultural Polemics in Antiquity". Journal of Jewish Studies. 49 (2): 306–333. .

- Russell, Paul S. (2005). "Nisibis as the Background to the Life of Ephrem the Syrian" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 8 (2): 179–235. S2CID 212688633.

- Ruzer, Serge (2014). "Hebrew versus Aramaic as Jesus' Language: Notes on Early Opinions by Syriac Authors". The Language Environment of First Century Judaea. Leiden-Boston: Brill. pp. 182–205. ISBN 9789004264410.

- Simmons, Ernest (1959). The Fathers and Doctors of the Church. Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Company.

- Toepel, Alexander (2013). "The Cave of Treasures: A new Translation and Introduction". Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. Vol. 1. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 531–584. ISBN 9780802827395.

- Wickes, Jeffrey (2015). "Mapping the Literary Landscape of Ephrem's Theology of Divine Names". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 69: 1–14. JSTOR 26497707.

- Wood, Philip (2007). Panicker, Geevarghese; Thekeparampil, Rev. Jacob; Kalakudi, Abraham (eds.). "Syrian Identity in the Cave of Treasures". The Harp. 22: 131–140. ISBN 9781463233112.

- Wood, Philip (2012). "Syriac and the Syrians". The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 170–194. ISBN 9780190277536.

External links

- Margonitho: Mor Ephrem the Syrian

- Anastasis article

- Hugoye: Influence of Saint Ephraim the Syrian, part 1

- Hugoye: Influence of Saint Ephraim the Syrian, part 2

- Encyclopædia Britannica 1911: "Ephraem Syrus"

- "St. Ephraem 'Faith Adoring the Mystery'". Archived from the original on 2008-06-13.

- Benedict XVI on St. Ephrem and his role in history

- Lewis E 235b Grammatical treatise (Ad correctionem eorum qui virtuose vivunt) at OPenn