Equatoria

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2012) |

Equatoria | |

|---|---|

Region | |

| Motto: God Is Our Strength | |

UTC+2 (CAT) | |

| Area code | 211 |

Equatoria is the southernmost region of South Sudan, along the upper reaches of the White Nile and the border between South Sudan and Uganda. Juba, the national capital and the largest city in South Sudan, is located in Equatoria. Originally a province of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, it also contained most of northern parts of present-day Uganda, including Lake Albert and West Nile. It was an idealistic effort to create a model state in the interior of Africa that never consisted of more than a handful of adventurers and soldiers in isolated outposts.[1]

Equatoria was established by

. The last two former areas of Equatoria, Lake Albert and West Nile are now situated in Uganda.Under

Geography

Administrative divisions

Equatoria consists of the following states:

Between October 2015 and February 2020, Equatoria consisted of the following states:

- Amadi State

- Gbudwe State

- Maridi State

- Tambura State

- Imatong State

- Torit State

- Kapoeta State

- Jubek State

- Terekeka State

- Yei River State

People

The people of Equatoria are traditionally peasants or nomads belonging to numerous ethnic groups. They live in the counties of

Languages

Other than Arabic or (Arabi Juba) and English, the following languages are spoken in Equatoria according to Ethnologue.[2]

|

|

Culture

Due to the many years of the civil war, the Equatorian culture is heavily influenced by the countries neighboring Equatoria and hosting Equatorians. Many Equatorians fled to Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Central African Republic, Sudan, the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and Europe, where they interacted with the nationals and learnt their languages and culture. For most of those who remained in the country, or went North to Sudan and Egypt, they greatly assimilated Arabic culture.

Most Equatorians kept the core of their

History

Early history

In the 19th century,

Baker's attempt to create additional trading posts and control Equatoria was unsuccessful because villages surrounding Gondokoro were frequently bypassed by

At the end of Baker's service as governor, British general Charles George Gordon was appointed governor of Sudan. Gordon took over in 1874 and administered the region until 1876. He was more successful in creating additional trading posts in the area. In 1876, Gordon's views clashed with those of the Egyptian governor of Khartoum forcing him to go back to London.

In 1878 Gordon was succeeded by the Chief Medical Officer of the Equatoria province,

In 1881,

In 1898, the

British policy

Equatoria received little attention from the British prior to World War I. Equatoria was closed to outside influences and developed along indigenous lines. As a result, the region remained isolated and underdeveloped. Limited social services to the region were provided by Christian missionaries who opened schools and medical clinics. The education provided by the missionaries was mainly limited to learning English language and arithmetic.

Sudanese independence

In February 1953, the United Kingdom and Egypt reached an agreement providing for Sudanese self-government and self-determination. On January 1, 1956 Sudan gained independence from the British and Egyptian governments. The new state was under the control of the Arab led Khartoum government. The Arab Khartoum government had promised Southerners full participation in the political system, however, after independence the Khartoum government reneged on its promises. Southerners were denied participation in free elections and marginalized from political power. The government actions created resentment in the south that led to a mutiny by a group of Equatorians sparking the 21 year civil war (1955–1972 and 1983–2004).

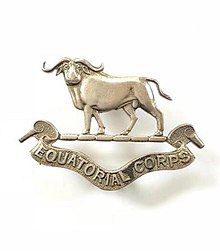

Equatoria Corps

Equatorians played an instrumental role in the struggle for autonomy in South Sudan. The origins of Sudan's civil war dates back to 1955, a year before independence, when it became clear the Arabs were going to take over the national government in Khartoum. Equatoria gave its name to the southernmost unit of the British Sudan Defence Force, formed during the Anglo-Egyptian administration. This was the Equatoria or Southern Corps.

On August 18, 1955, No. 2 Company of the Equatoria Corps

The Khartoum government sent its forces to arrest the rebels and capture anyone who supported their cause. By the early 1960s civilians believed to be Anya Nya sympathizers were arrested and shipped to Kodok concentration camp where they were tortured and killed. Some of the first detainees and survivors of the horrific torture at Kodok include Emmanuel Lukudu and Philip Lomodong Lako.[citation needed]

By 1969 the Equatorian rebels found support among foreign governments and were able to obtained weapons and supplies. Anya Nya recruits were trained in Israel where they also got some of their weapons. The Anya Nya rebels received financial assistance from Southern Sudanese and Southern exiles from the Middle East, Western Europe, and North America. By the late 1960s, the war had resulted in the deaths of half a million people and several hundred thousand southerners escaped to hide in the forests or to refugee camps in neighboring countries.

Anya Nya controlled the southern countryside while the government forces controlled the major towns in the region. The Anya Nya rebels were small in number and scattered all over the region making their operations ineffective. It is estimated that there were between 5,000 and 10,000 Anya Nya rebels.

On May 25, 1969, Colonel

Recent history

In 1983, President

In January 2020, the National Alliance for Democracy and Freedom Action (NADAFA) sought to join talks in Rome seeking to resolve political rifts within South Sudan.[4] The group is a coalition of holdout political groups including the People’s Democratic Movement (PDM), which was not signatory to the peace agreement signed by President Salva Kiir’s South Sudanese government in 2018. NADAFA sought a power-sharing arrangement in the new national government, with "People’s Constitutional Conventions" held in Equatoria, Upper Nile and Bahr al Ghazal.[5] In September 2020, Sudans Post published a message from Dr. Hakim Dario, the leader of NADAFA, expressing concern that the new nation had been named "South Sudan" and proposed that the nation should be called "Equatoria Federal Republic".[6]

On February 9, 2022, the Azande community in Yambio held a coronation ceremony for King Atoroba Peni Rikito Gbudue. The traditional royal title was last held by King Rikito's great-grandfather King Gbudue, who died in 1905.[7] Some neighboring cultural groups such as the Maridi and Balanda people wrote letters to the new king, warning him that they would not be subjects to the restored kingdom, with the Maridi letter specifically rejecting any ethnic political divisions, saying "We stand to promote the Republic of South Sudan, not the culture of a specific group.” [8] However, Badagbu Daniel Rimbasa, the king's brother, stated that the new king will not participate in politics. “It’s purely promotion of our culture and its preservation and heritage, not political.”[9]

Notable Equatorians

- Samuel Baker, 1st Governor of Equatoria 1870–1874

- Charles Gordon, 2nd Governor of Equatoria 1874–1876

- King Gbudwe, Azande King 1800's–1905

- King Atoroba Peni Rikito Gbudue, Azande King since February 9 2022

- Saturnino Ohure, allegedly fired the first shot in the First Sudanese Civil War

- Joseph Oduho

- Joseph Lagu

- Elia Kuzee

- Joseph James Tombura

- Aggrey Jaden

- Alison Monani Magaya

- Peter Cirillo

- Isaah Paul

- Oliver Batali Albino

- Samson L. Kwaje

- Cirino Hiteng Ofuho

- Beatrice Wani-Noah

- Elias Taban, Bishop, founder of the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Sudan

- Hakim Dario, Founder Equatoria Peoples' Alliance (EPA)

References

- ISBN 978-0060956394.

- ^ Languages of South Sudan. Ethnologue, 22nd edition.

- ^ Poggo, Scopas (2008). The First Sudanese Civil War: Africans, Arabs, and Israelis in the Southern Sudan, 1955-1972. Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 31, 40.; Robert O. Collins, Civil wars and revolution in the Sudan: essays on the Sudan, 2005, p.140

- ^ "Holdout opposition coalition seeks to join Rome talks". Radio Tamazuj. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "South Sudan holdout opposition alliance welcomes EU sanctions threat". Sudans Post. 2 May 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Equatoria Federal Republic not South Sudan". Sudans Post. 27 September 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Azande community installs new King, pledges to preserve culture". Radio Tamzuj. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Other Western Equatoria communities say they cannot be subjects of restored Azande Kingdom". Radio Tamazuj. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "South Sudan kingdom restored after 117 years". The Star (Kenya). Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- R. Gray, A History of the Southern Sudan, 1839–1889 (London, 1961).

- Iain R. Smith, The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition 1886–1890 (Oxford University Press, 1972).

- Alice Moore-Harell, Egypt's African Empire: Samuel Baker, Charles Gordon and the Creation of Equatoria (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2010).