Ore Mountains

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2021) |

| Ore Mountains | |

|---|---|

| Erz Mountains Krušné Mountains | |

Reservoir near Myslivny | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Klínovec |

| Elevation | 1,244 m (4,081 ft) |

| Coordinates | 50°23′46″N 12°58′04″E / 50.39611°N 12.96778°E |

| Naming | |

| Native name |

|

| Geography | |

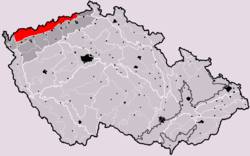

| Countries | Czech Republic and Germany |

| Regions/States | Karlovy Vary, Ústí nad Labem and Saxony |

| Range coordinates | 50°30′N 13°00′E / 50.500°N 13.000°E |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Variscan |

| Age of rock | Paleozoic |

| Type of rock | sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous rocks |

| Official name | Erzgebirge/Krušnohoří Mining Region |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | (ii), (iii), (iv) |

| Designated | 2019 |

| Reference no. | 1478 |

| Region | Western Europe/Eastern Europe |

The Ore Mountains (German: Erzgebirge, Czech: Krušné hory) lie along the Czech–German border, separating the historical regions of Bohemia in the Czech Republic and Saxony in Germany. The highest peaks are the Klínovec in the Czech Republic (German: Keilberg) at 1,244 metres (4,081 ft) above sea level and the Fichtelberg in Germany at 1,215 metres (3,986 ft).

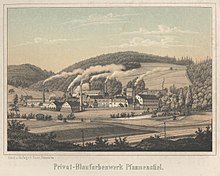

The Ore Mountains have been intensively reshaped by human intervention and a diverse cultural landscape has developed. Mining in particular, with its tips, dams, ditches and sinkholes, directly shaped the landscape and the habitats of plants and animals in many places. The region was also the setting of the earliest stages of the early modern transformation of mining and metallurgy from a craft to a large-scale industry, a process that preceded and enabled the later Industrial Revolution.

The higher altitudes from around 500 m above sea level on the German side belong to the Ore Mountains/Vogtland Nature Park – the largest of its kind in Germany with a length of 120 km. The eastern Ore Mountains are protected landscape. Other smaller areas on the German and Czech sides are protected as nature reserves and natural monuments. On the ridges there are also several larger raised bogs that are only fed by rainwater. The mountains are popular for hiking and there are winter sports areas at higher elevations. In 2019, the region became a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[1]

Name

In English, the Ore /ɔːr/ Mountains are sometimes referred to as the Ore Mountain Range, but are also sometimes called the Erzgebirge [ˈeːɐ̯tsɡəˌbɪʁɡə] or Erz Mountains /ɛərts, ɜːrts/ after their German name or the Krušné Mountains /ˈkrʊʃni, -neɪ/ after their Czech name. In Czech they are the Krušné hory [ˈkruʃnɛː ˈhorɪ], from old Czech krušec, meaning "piece of ore", and were historically known as Rudohoří, a literal translation of the German name, and Vyšehory, meaning "high mountains".[2] In Upper Sorbian the mountains are known as the Rudne horiny. The German and Upper Sorbian names, as well as the historical Czech Rudohoří, literally mean "ore mountains".

Geography

Geology

The Ore Mountains are geologically considered to be one of the most heavily researched mountain ranges in the world. The Ore Mountains are a

During the

), exposing the hard rocks.In the Tertiary period these mountain remnants came under heavy pressure as a result of plate tectonic processes during which the Alps were formed and the North American and Eurasian plates were separated. As the rock of the Ore Mountains was too brittle to be folded, it shattered into an independent fault block which was uplifted and tilted to the northwest. This can be very clearly seen at a height of 807 m above sea level (NN) on the mountain of Komáří vížka which lies on the Czech side, east of Zinnwald-Georgenfeld, right on the edge of the fault block.

Consequently, it is a

The main geologic feature in the Ore Mountains is the Late

The most important rocks occurring in the Ore Mountains are

To the north of the Ore Mountains, west of

Terrain

The western part of the Ore Mountains is home to the two highest peaks of the range: Klínovec, located in the Czech part, with an altitude of 1,244 metres (4,081 ft) and Fichtelberg, the highest mountain of Saxony, Germany, at 1,214 metres (3,983 ft). The Ore Mountains are part of a larger mountain system and adjoin the Fichtel Mountains to the west and the Elbe Sandstone Mountains to the east. Past the River Elbe, the mountain chain continues as the Lusatian Mountains. While the mountains slope gently away in the northern (German) part, the southern (Czech) slopes are rather steep.

Topography

The Ore Mountains are oriented in a southwest–northeast direction and are about 150 km long and, on average, about 40 km wide. From a

To the east it is adjoined by the

The topographical transition from the Western and Central Ore Mountains to the

The Ore Mountains belong to the

According to cultural tradition, Zwickau is seen historically as part of the Ore Mountains, Chemnitz is seen historically as just lying outside them, but

Notable peaks

The highest mountain in the Ore Mountains is the

Important rivers

From west to east:

- Zwota / Svatava (Zwodau)

- Rolava (Rohlau)

- Zwickauer Mulde

- Freiberger Mulde

- Red Weißeritz and Wild Weißeritz

- Müglitz

- Gottleuba

Natural regions in the Saxon Ore Mountains

In the division of Germany into natural regions that was carried out Germany-wide in the 1950s[5] the Ore Mountains formed major unit group 42:

- 42 Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge)

- 420 Southern slopes of the Ore Mountains (Südabdachung des Erzgebirges)

- 421 Upper Western Ore Mountains (Oberes Westerzgebirge)

- 422 Upper Eastern Ore Mountains (Oberes Osterzgebirge)

- 423 Lower Western Ore Mountains (Unteres Westerzgebirge)

- 424 Lower Eastern Ore Mountains (Unteres Osterzgebirge)

Even after the reclassification of natural regions by the

The current division therefore looks as follows:[6]

- Saxon Highlands and Uplands (Sächsisches Bergland und Mittelgebirge)

- Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge)

- Western Ore Mountains (Westerzgebirge)

- Central Ore Mountains (Mittelerzgebirge)

- Eastern Ore Mountains (Osterzgebirge)

- Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge)

The geographic unit of the Southern Slopes of the Ore Mountains remains unchanged under the title of Southern Ore Mountains (Süderzgebirge).

Climate

The climate of the higher regions of the Ore Mountains is characterised as distinctly harsh. Temperatures are considerably lower all year round than in the lowlands, and the summer is noticeably shorter and cool days are frequent. The average annual temperatures only reach values of 3 to 5 °C. In Oberwiesenthal, at a height of 922 m above sea level (NN), on average only about 140 frost-free days per year are observed. Based on reports of earlier chroniclers, the climate of the upper Ore Mountains in past centuries must have been even harsher than it is today. Historic sources describe hard winters in which cattle froze to death in their stables, and occasionally houses and cellars were snowed in even after snowfalls in April. The population was regularly cut off from the outside world.[7] The upper Ore Mountains was therefore nicknamed Saxon Siberia already in the 18th century.[8]

The fault block mountain range that climbs from northwest to southeast, and which enables prolonged rain to fall as

As a result of the climate and the heavy amounts of snow a natural

-

Climatic diagram of Annaberg-Buchholz[9]

-

Climatic diagram of Freiberg[9]

-

Climatic diagram of the Fichtelberg[9]

-

Climatic diagram of Zinnwald-Georgenfeld[9]

History

Etymology of the name

The term Saltusbohemicus ("Bohemian Forest") for the region emerged in the 12th century. In the German language the names Böhmischer Wald, Beheimer Wald, Behmerwald or Böhmerwald were used, in Czech the name Český les. The last-mentioned names are used today[when?] for the mountain range along the Czech Republic's southwestern border (see: Bohemian Forest).

From earlier research, other names for the Ore Mountains have also appeared in a few older written records. However, the names Hircanus Saltus (Hercynian Forest) or Fergunna, which appeared in the 9th century, were only used in a general sense for the vast forests of the Central Uplands. Frequently the term Miriquidi is used to refer directly to the Ore Mountains, but it only surfaces twice in the 10th and early 11th centuries, and these sources do not permit a clear identification with the ancient forest that formerly covered the whole of the Ore Mountains and its foreland.

Following the

The mountains are sometimes divided into the Saxon Ore Mountains and Bohemian Ore Mountains. A similarly named range in Slovakia is usually known as the Slovak Ore Mountains.

Economic history

Europe's earliest mining district appears to be located in Erzgebirge, dated to 2500 BC. From there tin was

From the time of the first wave of settlement, the history of the Ore Mountains has been heavily influenced by its economic development, especially that of the mining industry.

Settlement in the Ore Mountains was slow to begin with, especially on the Bohemian side. The harsh climate and short growing seasons hindered the cultivation of agricultural products. Nevertheless, settlements were supported by the aristocratic

In 1168, as a result of settlement in the early 12th century at the northern edge of the Ore Mountains, the first

In the 13th century, colonization of the mountains took place only sporadically along the Bohemian Way (antiqua Bohemiae semita). It was here that

Mining on the Bohemian side of the mountains probably began in the 14th century. An indication of this is a contract between Boresch of Riesenburg and the Ossegg abbot, Gerwig, in which the division of revenue derived from ore was agreed. Grains of tin (Zinnkörner or Graupen) were obtained at that time in the Seiffen mining area and gave the Bohemian mining town of Graupen (Czech Krupka) its name.

With the further settlement of the Ore Mountains in the 15th century, new, rich, ore deposits were eventually discovered around

In the 16th century the Ore Mountains became the heartland of the Central European mining industry. New ore discoveries attracted more and more people, and the number of residents on the Saxon side of the mountains continued to rise rapidly. Bohemia, in addition to migration from within the country, also received migration from elsewhere, mainly of German miners, who settled in the mountain villages and in the towns at the edge of the mountains.

Under Emperor

Ore mining largely came to a standstill in the 17th century, especially after the

After the discovery of the

Towards the end of the 19th century, mining slowly declined again.

But even the excavation of the

Mining in the Ore Mountains was given new life during the

In 1789 the

For the third time in history, thousands of people poured into the Ore Mountains to build a new life. The principal mining areas were located around

Mining operations in

The mountains that until the late 11th (and early 12th century) were covered in dense forests were almost completely transformed into a cultural landscape by the mining industry and by settlement. The population density is high right up into the upper regions of the mountains. For example, Oberwiesenthal, the highest town in Germany, lies in the Ore Mountains, and neighbouring Boží Dar (German: Gottesgab) on the Czech side, is actually the highest town in Central Europe. Only on the relatively inaccessible, less climatically favourable ridges are there still large, contiguous forests, but since the 18th century these have been managed economically. Due to the high demand for timber by the mining and smelting industries, where it was needed for pit props and fuel, large-scale deforestation took place from the 12th century onwards, and even the forests owned by the nobility could not cover the growing demand for wood. In the 18th century, industries were encouraged to use coal as fuel instead of timber in order to preserve the forests, and this was enforced in the 19th century. In the early 1960s the first signs of forest dieback were seen in the Eastern Ore Mountains near Altenberg and Reitzenhain, after local damage to the forests had become apparent since the 19th century as a result of smelter smoke (Hüttenrauch). The German population of the Bohemian part of the Ore Mountains was expelled in 1945 in accordance with to the Beneš decrees.

Nature

The upper western part of the Ore Mountains, known in German as Erzgebirge, belongs to the Ore Mountains/Vogtland Nature Park. The eastern part, called the Eastern Ore Mountains (Osterzgebirge), is a protected landscape. Further small areas are nature reserves and natural monuments, and are protected by the state.

Nature reserves

- Germany (selection)

- Western Ore Mountains Special Protected Area (SPA Westerzgebirge)

- Valley of the Große Bockau Special Area of Conservation (FFH-Gebiet Tal der Großen Bockau)

- Mountain meadows in the Eastern Ore Mountains major nature conservation project (Naturschutzgroßprojekt Bergwiesen im Osterzgebirge)

- Geisingberg nature reserve, 314.00 ha

- Georgenfelder Hochmoor nature reserve, 12.45 ha

- Fürstenau Heath (Fürstenauer Heide) nature reserve (Black Grouse conservation area near Fürstenau), 7.24 ha

- Kleiner Kranichsee nature reserve, 28.97 ha

- Großer Kranichsee nature reserve, 611.00 ha

- Hermannsdorf Meadows (Hermannsdorfer Wiesen) nature reserve, 185.00 ha

- The Czech Republic (selection)

- NPR Božídarské rašeliniště, 929.57 ha (1965)

- NPR Velké jeřábí jezero, 26.9 ha (1938)

- NPR Velký močál, 50.27 ha (1969)

- NPR Novodomské rašeliniště, 230 ha (1967)

- PR Černý rybník, 32.56 ha (1993)

- PR Malé jeřábí jezero, 6.02 ha (1962)

- PR Ryžovna, 20 ha

Mining and Pollution

Ever since the settlement in mediaeval times, the Ore Mountains were farmed intensively. This led to widespread clearings of the originally dense forest, also to keep up with the enormous need for wood in mining and metallurgy. Mining including the construction of dumps, impoundments, and ditches in many places also directly shaped the scenery and the habitats of plants and animals.

Evidence for local forest dieback due to the smoke from smelting furnaces was first noted the 19th century. In the 20th century, several mountain crests were deforested because of their climatically exposed location. Thus, in recent years, mixed forests are cultivated which are more resistant to weather effects and pests than the traditional monocultures of spruces.

The Ore Mountains/Vogtland Nature Park

Human interventions have created a unique cultural landscape with a large number of typical biotopes which are worthy of protection such as mountain meadows and wetlands. Today, even old mining spoil heaps offer a living environment for a variety of plants and animals. 61% of the area of

Economy

The German part of the Ore Mountains is one of the major business locations in Saxony. The region has a high density of industrial operations. Since 2000, the number of industrial workers has risen against the Germany-wide trend by about 20 percent. Typical of the Ore Mountains are mainly small, often owner-managed, businesses.

The economic strengths of the Ore Mountains are mainly in manufacturing. 63 percent of the industrial workforce is employed in the metalworking and electrical industry.

Only of minor importance is the formerly dominant textile and clothing industry (5 percent of industrial net product) and the food industry. The newly established chemical, leather and plastic industries and the industries traditionally based in the Ore Mountains-based – wood, paper, furniture, glass and ceramics works – each contribute about 14 percent of regional net product.

Mining, the essential historical basis of industrial development in the Ore Mountains, currently plays only a minor economic role on the Saxon side of the border. For example, in

In the Czech part of the Ore Mountains, tourism has gained a certain importance, even though the Giant Mountains are more important for domestic tourism. In addition, mining still plays a greater role, particularly coal mining in the southern forelands of the Ore Mountains. Europe's largest deposits of lithium-bearing mica zinnwaldite in Cínovec, a Czech village between town of Dubí and the border with Germany which gave its old German name Zinnwald to the mineral, are expected to be mined starting 2019 (as of June 2017).[19][20]

Tourism

When several

In 1924 the

Based on the historical

In the Advent and Christmas season the Ore Mountains, with its distinct traditions, Christmas markets and miners' parades is also a popular destination for short breaks.

Very unique and popular spa resort are located in Jáchymov in the Czech Republic. In the historical town are some of the most unique spas in the world. Musculoskeletal system is treated here with radon water and direct irradiation. This treatment is suitable for vascular diseases. Furthermore, for the nerve, rheumatic diseases or inflammation of nerves. The most important use is the treatment of diseases of the musculoskeletal system (gout etc.). The spa was founded in 1906. One of the spa buildings is Radium Palace – spa neoclassical hotel palace, already at the time of its establishment in 1912 was one of the best that Europe could offer in the field of spas.

With 960,963 guests staying for 2,937,204 nights in 2007[21] the Ore Mountains and West Saxony is the most important Saxon holiday destination after the cities, and tourism is an important economic factor in the region. Since 2004 the Ore Mountain Tourist Association (Tourismusverband Erzgebirge) has offered the Ore Mountain Card (ErzgebirgsCard) with which over 100 museums, castles, heritage railways and other sights may be visited free of charge.

UNESCO World Heritage Site

In 2019, the following 22 mines or mining complexes were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List as the Erzgebirge/Krušnohoří Mining Region.[1]

| Site | Country | Location | Area ha (acre) |

Buffer Area ha (acre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dippoldiswalde Medieval Silver Mines | Germany | 50°53′48″N 13°40′26″E / 50.89667°N 13.67389°E | 536.871 | - |

| Altenberg-Zinnwald Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°45′50″N 13°46′13″E / 50.76389°N 13.77028°E | 269.367 | 1,716.705 |

| Lauenstein Administrative Centre | Germany | 50°47′07″N 13°49′23″E / 50.78528°N 13.82306°E | 2.926 | 18.885 |

| Freiberg Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°55′05″N 13°20′40″E / 50.91806°N 13.34444°E | 624.434 | 2,202.532 |

| Hoher Forst Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°37′10″N 12°34′07″E / 50.61944°N 12.56861°E | 44.799 | 103.604 |

| Schneeberg Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°35′44″N 12°38′39″E / 50.59556°N 12.64417°E | 218.15 | 670.351 |

| Schindlers Werk Smalt Works | Germany | 50°32′31″N 12°39′30″E / 50.54194°N 12.65833°E | 2.659 | 2.7 |

| Annaberg-Frohnau Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°34′52″N 12°59′33″E / 50.58111°N 12.99250°E | 191.994 | 926.131 |

| Pöhlberg Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°34′32″N 13°02′43″E / 50.57556°N 13.04528°E | 118.94 | - |

| Buchholz Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°33′47″N 12°59′20″E / 50.56306°N 12.98889°E | 37.346 | - |

| Marienberg Mining Town | Germany | 50°39′02″N 13°09′47″E / 50.65056°N 13.16306°E | 25.306 | 44.603 |

| Lauta Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°39′50″N 13°08′33″E / 50.66389°N 13.14250°E | 20.592 | - |

| Ehrenfriedersdorf Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°38′35″N 12°58′35″E / 50.64306°N 12.97639°E | 71.148 | 891.575 |

| Grünthal Silver-Copper Liquation Works | Germany | 50°39′01″N 13°22′08″E / 50.65028°N 13.36889°E | 12.917 | 25.294 |

| Eibenstock Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°30′45″N 12°35′57″E / 50.51250°N 12.59917°E | 100.656 | 248.312 |

| Rother Berg Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°31′12″N 12°47′15″E / 50.52000°N 12.78750°E | 4.519 | 38.556 |

| Uranium Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°38′00″N 12°41′08″E / 50.63333°N 12.68556°E | 811.213 | 746.263 |

| Jáchymov Mining Landscape | Czech Republic | 50°22′16″N 12°54′47″E / 50.37111°N 12.91306°E | 738.452 | 637.9 |

| Abertamy – Boží Dar – Horní Blatná – Mining Landscape | Czech Republic | 50°24′23″N 12°50′14″E / 50.40639°N 12.83722°E | 2,608.279 | 3,011.867 |

| The Red Tower of Death | Czech Republic | 50°19′44″N 12°57′12″E / 50.32889°N 12.95333°E | 0.2 | 2.804 |

| Krupka Mining Landscape | Czech Republic | 50°41′6.″N 13°51′19″E / 50.68500°N 13.85528°E | 317.565 | 474.299 |

| Mědník Hill Mining Landscape | Czech Republic | 50°25′27″N 13°06′41″E / 50.42417°N 13.11139°E | 7.724 | 1,255.41 |

Culture

The culture of the Ore Mountains was shaped mainly by mining that goes back to the Middle Ages. The old saying, coined here, that "everything comes from the mine" (Alles kommt vom Bergwerk her!) refers to many areas of life in the region, from its landscape, to its handicrafts, industry, living traditions and folk art. The visitor may recognise this on his arrival from the normal everyday greeting Glück Auf! that is used in the region.

The Ore Mountains has its own dialect, Erzgebirgisch, which sits on the boundary between Upper German and Central German and is not therefore uniform.

The first important native dialect poet of the Ore Mountains was Christian Gottlob Wild in the early 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, Hans Soph, Stephan Dietrich and especially Anton Günther were active; their works have a lasting impact to this day in Ore Mountain songs and writings. Erzgebirgisch songs were later popularised by various local groups. The most famous include the Preßnitzer Musikanten, Geschwister Caldarelli, Zschorlauer Nachtigallen, the Erzgebirgsensemble Aue and Joachim Süß and his Ensemble. Today it is mainly De Randfichten, but also groups like Wind, Sand und Sterne, De Ranzn, De Krippelkiefern, De Erbschleicher and Schluckauf that sing in the Erzgebirgisch dialect.

The Ore Mountains are nationally known for their variety of customs at

In addition to the Christmas markets and other smaller traditional and modern folk festivals, the

Also interesting is Ore Mountain cuisine, which is simple, but rich in tradition.

In 2019 the region was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List as the Erzgebirge/Krušnohoří Mining Region.[1]

Gallery

-

Stürmer mountain in March 2008

-

Old adit near Johanngeorgenstadt

-

Jáchymov town hall

-

Klínovec mountain

-

Uranite from the Ore Mountains

-

Castle Krupka (the Czech Republic)

-

Karlovy Vary (Karlsbad in German, Carlsbad in English) is one of the most famous spas in the world. They are located below the Ore Mountains on the river Ohře

See also

- Erzgebirgisch, the local German dialect

- List of mountains in the Ore Mountains

- List of regions of Saxony

- Hans Carl von Carlowitz (1645–1714), mining and forestry expert

- Saxon Highlands and Uplands

Footnotes

References

- ^ a b c "Erzgebirge/Krušnohoří Mining Region". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ "Krušné hory". rozhlas.cz. 20 January 2004. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ Elkins, T H (1972). Germany (3rd ed.). London: Chatto & Windus, p. 291. ASIN B0011Z9KJA.

- ^ a b c Heinrich, E. Wm. (1958). Mineralogy and Geology of Radioactive Raw Materials. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. pp. 283–284.

- Handbuch der naturräumlichen Gliederung Deutschlands. Remagen/Bad Godesberg: Bundesanstalt für Landeskunde.

- ^ Map of natural regions in Saxony Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine at www.umwelt.sachsen.de (pdf, 859 kB)

- ^ Athenaum sive Universitas Boemo-Zinnwaldensis von 1717, published by Peter Schenk.

- ^ Anonymous (1775). Mineralogische Geschichte des Sächsischen Erzgebirges. Hamburg: Carl Ernst Bohn.

- ^ a b c d "Deutscher Wetterdienst, Normalperiode 1961–1990". dwd.de. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ Novotný, Michal (20 January 2004). "Krušné hory". Český rozhlas Regina. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ISBN 0-904357-81-3.

- ^ ISBN 0-7524-1452-6.

- ISBN 1-84171-564-6.

- ISBN 9963-8102-3-3.

- ^ National Geographic. June 2002. p. 1. Ask Us.

- ISBN 9780143116721.

- ISBN 9781610396547.

- ^ Peter Diehl: Altstandorte des Uranbergbaus in Sachsen pdf file Archived 28 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Seidler, Christoph (2 May 2012). "Mining Revival: German Solar Firm Goes Hunting For Lithium". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2018 – via Spiegel Online.

- ^ Muller, Robert (8 June 2017). "RPT-Miners eye Europe's largest lithium deposit in Czech Republic". reuters.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Stat Statistics Office for the Free State of Saxony, Accommodation statistics (including campers)". sachsen.de. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

Further reading

- Harald Häckel, Joachim Kunze: Unser schönes Erzgebirge. 4th edition, Häckel 2001, ISBN 3-9803680-0-9

- Peter Rölke (Hrsg.): Wander- & Naturführer Osterzgebirge, Berg- & Naturverlag Rölke, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-934514-20-1

- Müller, Ralph u.a.: Wander- & Naturführer Westerzgebirge, Berg- & Naturverlag Rölke, Dresden 2002, ISBN 3-934514-11-1

- NN: Kompass Karten: Erzgebirge West, Mitte, Ost. Wander- und Radwanderkarte 1:50.000, GPS kompatibel. Kompass Verlag, 2002, ISBN 3-85491-954-9

- NN: Erzgebirge, Vogtland, Chemnitz. HB Bildatlas, Heft No. 171. 2., akt. Aufl. 2001, ISBN 3-616-06271-3

- Peter Rochhaus: Berühmte Erzgebirger in Daten und Geschichten. Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2006, ISBN 978-3-86680-020-5

- Siegfried Roßberg: Die Entwicklung des Verkehrswesens im Erzgebirge – Der Kraftverkehr. Bildverlag Böttger, Witzschdorf 2005, ISBN 3-9808250-9-4

- Bernd Wurlitzer: Erzgebirge, Vogtland. Marco Polo Reiseführer. 5., akt. Aufl. Mairs Geographischer Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-8297-0005-9

- Emmermann, Rolf; Tischendorf, Gerhard; Trumbull, Robert B; Möller, Peter (1994): Magmatism and Metallogeny in the Erzgebirge. Geowissenschaften; 12; 337–341;

External links

- The Ore Mountains tourist website for the German Ore Mountains

- Official website from the state saxony

- Ore mountains tourist website for the Czech Ore Mountains

- Ore Mountains article at www.britannica.com

- UNESCO World Heritage Project "Montanregion Erzgebirge"

- Animation of geological formation of the Ore Mountains

- http://www.westerzgebirge.com/htm/erzgebirge-personen.htm

![Climatic diagram of Annaberg-Buchholz[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5a/Klimadiagramm-deutsch-Annaberg-Buchholz_%28SN%29-Deutschland.png/260px-Klimadiagramm-deutsch-Annaberg-Buchholz_%28SN%29-Deutschland.png)

![Climatic diagram of Freiberg[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d2/Klimadiagramm-deutsch-Freiberg_%28SN%29-Deutschland.png/260px-Klimadiagramm-deutsch-Freiberg_%28SN%29-Deutschland.png)

![Climatic diagram of the Fichtelberg[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ac/Klimadiagramm-deutsch-Fichtelberg_%28SN%29-Deutschland.png/260px-Klimadiagramm-deutsch-Fichtelberg_%28SN%29-Deutschland.png)

![Climatic diagram of Zinnwald-Georgenfeld[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/84/Klimadiagramm-deutsch-Zinnwald-Georgenfeld_%28SN%29-Deutschland.png/260px-Klimadiagramm-deutsch-Zinnwald-Georgenfeld_%28SN%29-Deutschland.png)