Temple of Eshmun

𐤁𐤕 𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍 | |

Government of Lebanon | |

| Management | Directorate General of Antiquities[1] |

|---|---|

| Public access | Yes (for a fee) |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | Phoenician, Achaemenid, Hellenistic and Roman |

The Temple of Eshmun (

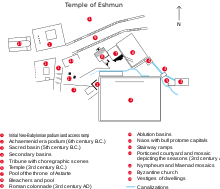

The sanctuary consists of an esplanade and a grand court limited by a huge limestone terrace wall that supports a monumental podium which was once topped by Eshmun's Greco-Persian style marble temple. The sanctuary features a series of ritual ablution basins fed by canals channeling water from the Asclepius river (modern Awali) and from the sacred "YDLL" spring;[nb 1] these installations were used for therapeutic and purificatory purposes that characterize the cult of Eshmun. The sanctuary site has yielded many artifacts of value, especially those inscribed with Phoenician texts, such as the Bodashtart inscriptions and the Eshmun inscription, providing valuable insight into the site's history and that of ancient Sidon.

The Eshmun Temple was improved during the early Roman Empire with a colonnade street, but declined after earthquakes and fell into oblivion as Christianity replaced polytheism and its large limestone blocks were used to build later structures. The temple site was rediscovered in 1900 by local treasure hunters who stirred the curiosity of international scholars. Maurice Dunand, a French archaeologist, thoroughly excavated the site from 1963 until the beginning of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975. After the end of the hostilities and the retreat of Israel from Southern Lebanon, the site was rehabilitated and inscribed to the World Heritage Site tentative list.

Eshmun

Eshmun (

From a historical perspective, the first written mention of Eshmun goes back to 754 BC, the date of the signing of the treaty between Assyrian king Ashur-nirari V and Mati'el, king of Arpad; Eshmun figures in the text as a patron of the treaty.[4] Eshmun was identified with Asclepius as a result of the Hellenic influence over Phoenicia; the earliest evidence of this equation is given by coins from Amrit and Acre from the third century BC. This fact is exemplified by the Hellenized names of the Awali river which was dubbed Asclepius fluvius, and the Eshmun Temple's surrounding groves, known as the groves of Asclepius.[2]

History

Historical background

In the 9th century BC, the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II conquered the Lebanon mountain range and its coastal cities. The new sovereigns exacted tribute from Sidon, along with every other Phoenician city. These payments stimulated Sidon's search for new means of provisioning and furthered Phoenician emigration and expansion, which peaked in the 8th century BC.[4] When Assyrian king Sargon II died in 705 BC, King Luli joined with the Egyptians and Judah in an unsuccessful rebellion against Assyrian rule,[5] but was forced to flee to Kition (modern Larnaca in Cyprus) with the arrival of the Assyrian army headed by Sennacherib, Sargon II's son and successor. Sennacherib instated Ittobaal on the throne of Sidon and reimposed the annual tribute.[5][6] When Abdi-Milkutti ascended to Sidon's throne in 680 BC, he also rebelled against the Assyrians. In response, the Assyrian king Esarhaddon laid siege to the city. Abdi-Milkutti was captured and beheaded in 677 BC after a three-year siege, while his city was destroyed and renamed Kar-Ashur-aha-iddina (the harbor of Esarhaddon). Sidon was stripped of its territory, which was awarded to Baal I, the king of rival Tyre, and loyal vassal to Esarhaddon.[4][7][8] Baal I and Esarhaddon signed a treaty in 675 in which Eshmun's name features as one of the deities invoked as guarantors of the covenant.[nb 3][3][9]

Construction

Sidon returned to its former level of prosperity while Tyre was besieged for 13 years (586–573 BC) by the Chaldean king Nebuchadnezzar II.[10] Nevertheless, the Sidonian king was still held in exile at the court of Babylon.[4][11] Sidon reclaimed its former standing as Phoenicia's chief city in the Achaemenid Empire (c.529–333 BC).[4][11][12] Eshmunazar I, a priest of Astarte, and the founder of his namesake dynasty, became king around the time of the Achaemenid conquest of the Levant. Archaeological evidence suggest that, at the time of the advent of the Eshmunazar dynasty, there already was a cultic space on the site of the temple, but there were no monumental constructions yet. Originally, the center of worship may have been a cave or a spring.[13] In the following years, Xerxes I awarded king Eshmunazar II with the Sharon plain[nb 4] for employing Sidon's fleet in his service during the Greco-Persian Wars.[4][11][12] Eshmunazar II displayed his new-found wealth by constructing numerous temples to Sidonian divinities. Inscriptions found on the king's sarcophagus reveal that he and his mother, Amoashtart, built temples to the gods of Sidon,[4] including the Temple of Eshmun by the "Ydll source near the cistern".[14][15]

As the Bodashtart inscriptions on the foundations of the monumental podium attest, construction of the sanctuary's podium did not begin until the reign of King Bodashtart.[16] The first set of inscriptions bears the name of Bodashtart alone, while the second contains his name and that of the crown prince Yatonmilk.[4][17] Thirty foundation inscriptions are known to date;[18] they were found concealed in the interior of the podium. The practice of intentional inscription concealment can be traced back to Mesopotamian roots, and it has parallels in the royal buildings of the Achaemenids in Persia and Elam.[19] A Phoenician inscription, located 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) upstream from the temple, that dates to the 7th year of Bodashtart's reign, alludes to water adduction works from the Awali river to the "Ydll" source that was used for ritual purification at the temple.[4][20]

Roman era and decline

The Eshmun sanctuary was damaged by an earthquake in the fourth century BC, which demolished the marble temple atop the podium; this structure was not rebuilt but many chapels and temples were later annexed at the base of the podium.

Modern discovery

Between 1737 and 1742,

After 1975

During the

Location

A number of ancient texts mention the Eshmun Temple and its location. The

Architecture and description

Built under

The pyramidal structure was superimposed during the

Widely known as the "Tribune of Eshmun" because of its shape, the altar of Eshmun is a white marble structure dating to the 4th century BC. It is 2.15 metres (7.1 ft) long by 2.26 metres (7.4 ft) wide and 2.17 metres (7.1 ft) tall.

Northeast of the site, another 3rd century BC temple stands adjacent to the Astarte chapel. Its 22-metre (72 ft) façade is built with large limestone blocks and displays a two-register relief decoration illustrating a

Function

Eshmun's cult enjoyed a particular importance at Sidon as he was the chief deity after 500 BC. Aside from the extramural sanctuary at Bustan el-Sheikh, Eshmun also had a temple within the city. The extramural Eshmun Temple was associated with purification and healing; ritual lustral ablutions were performed in the sanctuary's sacred basins supplemented by running water from the Asclepius River and the "Ydll" spring water which was considered to have a sacred character and therapeutic quality.[3][49] The healing attributions of Eshmun were combined with his divine consort Astarte's fertilizing powers; the latter had an annex chapel with a sacred paved pool within the Eshmun sanctuary.[49] Pilgrims from all over the ancient world flocked to the Eshmun Temple leaving votive traces of their devotion and proof of their cure.[50][51] There is evidence that from the 3rd century BC onwards there have been attempts to Hellenize the cult of Eshmun and to associate him with his Greek counterpart Asclepius, but the sanctuary retained its curative function.[52]

Artifacts and finds

Apart from the large decorative elements, carved friezes and mosaics which were left

Pillaging

Treasure hunters have sought out the Eshmun Temple since antiquity;

See also

- Phoenician sanctuary of Kharayeb – Historic temple remains in Lebanon

- Roman temple of Bziza – Cultural heritage building in Bziza, Lebanon

External links

Notes

- ISBN 9788876534270.

- ^ in Damascius's Life of Isidore and Photius's Bibliotheca Codex 242

- ^ Eshmun's name is transcribed in Akkadian as "Ia-su-mu-nu" in the Esarhaddon treaty

- ^ Territory south of Sidon from Mount Carmel to Jaffa

- ^ Discovered by the general consulate of France in Beirut Aimé Pérétié in 1855 in the Magharet Adloun necropolis, now on display in the Louvre

- ^ In Strabo's "Geographica"

- ^ The front register depicts from left to right: Eros, an unidentified matronly goddess who stands behind Artemis who is crowning an enthroned Leto. Apollo stands, playing a cithara next to Athena. Zeus appears next, enthroned with Hera standing by his side followed by standing figures of Amphitrite and Poseidon who stands at the right corner, his foot resting on a rock. On the right short side, turning the corner from Eros, the standing figures and the charioteer are identified as Demeter, Persephone and Helios. On the opposite short side, the three personages are assumed to be Dione, Aphrodite and Selene driving a quadriga. (from Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway's Fourth-century styles in Greek sculpture)

- Bulletin du Musée de Beyrouth, 20, (1967), p.53

- ^ The dedication reads: "This (is the) statue which Baalshillem son of King Ba'na, king of the Sidonians, son of King Abdamun, king of the Sidonians, son of King Baalshillem, king of the Sidonians, gave to his lord Eshmun at the "Ydll"-Spring. May he bless him" (taken from JCL Gibson's Textbook of Syrian Semitic inscriptions)

References

- ^ Lebanese Ministry of Culture. "Ministère de la Culture" (in French). Archived from the original (ministerial) on November 24, 2004. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ^ ISBN 9780766176713.

- ^ ISBN 9780802824912. Archivedfrom the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ ISBN 9789068316902.

- ^ ISBN 9780395652374.

- ISBN 9781628372175. Archivedfrom the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ OCLC 971421203.

- ISBN 9780521227179. Archivedfrom the original on August 17, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ISBN 9780802821737. Archivedfrom the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ISBN 9780521795432.

- ^ ISBN 9780835788014.

- ^ OCLC 45096924.

- ISBN 9788866870975. Archivedfrom the original on August 17, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ISBN 9780836957716.

- OCLC 62279815.

- from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ Elayi, Josette (2006). "An updated chronology of the reigns of Phoenician kings during the Persian period (539–333 BC)" (PDF). digitorient.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2016. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- ISBN 9788866870975. Archivedfrom the original on August 17, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021 – via JSTOR.

- OCLC 1136050029. Archivedfrom the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ OCLC 50646537.

- ^ ISBN 9780718921873.

- OCLC 7204600.

- ^ "Roman Eshmoun: Roman Colonnade, villa & stairway with nimphaeum". Archived from the original on July 14, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Lebanese Ministry of Tourism. "Eshmoun – A unique Phoenician site in Lebanon". Lebmania. Archived from the original on July 14, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2009.

- ^ .

- from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ a b Direction Générale des Antiquités, Ministère de la Culture et de l'Enseignement Supérieur, Monument: Temple d'Echmoun – UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in French), UNESCO, archived from the original on September 13, 2019, retrieved December 26, 2019

- OCLC 470949164.

- ^ Najjar, Charles; Tyma Daoudy (1999). The indispensable guide to Lebanon. Etudes et Consultations Economiques. p. 46.

- ISBN 9780704371675.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2019). "Temple d'Echmoun" [The temple of Eshmun]. UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in French). Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- OCLC 1103630119.

- ISBN 9782848190419.

- ISBN 9780809100293.

- OCLC 29031989.

- ISBN 9781741046090.

- ^ OCLC 12299065.

- ^ OCLC 47953853.

- ^ Stucky, Rolf A. (1998). "Le sanctuaire d'Echmoun à Sidon" [The sanctuary of Eshmun in Sidon] (PDF). National Museum News (in French) (7). Beirut: Directorate General of Antiquities (Lebanon): 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2021 – via AHL.

- ^ ISBN 9788881621415.

- ^ ISBN 9789953000381.

- ^ ISBN 9780299154707.

- ^ "Collections – The Hellenistic period (333 BC – 64 BC)". Beirut National Museum. Archived from the original (educational) on June 2, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2009.

- ISBN 9783909064199. Archivedfrom the original on July 31, 2023. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- PMID 14246298.

- OCLC 46500081.

- ^ from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ OCLC 1082376089.

- ^ OCLC 1390289985. Archivedfrom the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ^ ISBN 2-84289-344-1.

- ISBN 9789068310733.

- ISBN 9780198131991.

- ISBN 9781841272924.

- OCLC 52090604.

- ^ a b Makarem, May (December 4, 2009). "Qui est responsable du pillage du temple d'Echmoun – Six cent pièces issues du temple d'Echmoun circulent sur le marché mondial des antiquités" [Who is responsible for the looting of the Temple of Echmoun - Six hundred pieces from the Temple of Eshmun circulate on the world antiquities market]. L'Orient-Le Jour (in French) (12733 ed.). Beirut. p. 4.

- from the original on November 23, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

External links