Esophageal cancer

| Esophageal cancer | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Oesophageal cancer |

| Frequency | 746,000 affected as of 2015[7] |

| Deaths | 509,000 (2018)[8] |

Esophageal cancer is

The two main

Causes of the squamous-cell type include tobacco, alcohol, very hot drinks, poor diet, and chewing

The disease is diagnosed by

As of 2018, esophageal cancer was the eighth-most common cancer globally with 572,000 new cases during the year. It caused about 509,000 deaths that year, up from 345,000 in 1990.

Signs and symptoms

Prominent symptoms usually do not appear until the cancer has infiltrated over 60% of the circumference of the esophageal tube, by which time the tumor is already in an advanced stage.[14] Onset of symptoms is usually caused by narrowing of the tube due to the physical presence of the tumor.[15]

The first and the most common symptom is usually

The presence of the tumor may disrupt the normal

If the cancer has spread elsewhere, symptoms related to

Causes

The two main types (i.e.

Squamous-cell carcinoma

The two major risk factors for esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma are tobacco (smoking or

Other relevant risk factors include regular consumption of very hot drinks (over 65 °C or 149 °F)

Physical trauma may increase the risk.[24] This may include the drinking of very hot drinks.[3]

Adenocarcinoma

Male predominance is particularly strong in this type of esophageal cancer, which occurs about 7 to 10 times more frequently in men.[25] This imbalance may be related to the characteristics and interactions of other known risk factors, including acid reflux and obesity.[25]

GERD or Gastroesophageal reflux disease

The long-term erosive effects of acid reflux (an extremely common condition, also known as

Being obese or overweight both appear to be associated with increased risk.[29] The association with obesity seems to be the strongest of any type of obesity-related cancer, though the reasons for this remain unclear.[30] Abdominal obesity seems to be of particular relevance, given the closeness of its association with this type of cancer, as well as with both GERD and Barrett's esophagus.[30] This type of obesity is characteristic of men.[30] Physiologically, it stimulates GERD and also has other chronic inflammatory effects.[26]

Female hormones may also have a protective effect, as EAC is not only much less common in women but develops later in life, by an average of 20 years. Although studies of many reproductive factors have not produced a clear picture, risk seems to decline for the mother in line with prolonged periods of breastfeeding.[31]

Tobacco smoking increases risk, but the effect in esophageal adenocarcinoma is slight compared to that in squamous cell carcinoma, and alcohol has not been demonstrated to be a cause.[31]

Related conditions

- Head and neck cancer is associated with second primary tumors in the region, including esophageal squamous-cell carcinomas, due to field cancerization (i.e. a regional reaction to long-term carcinogenic exposure).[34][35]

- History of chest is a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma.[16]

- caustic substances is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma.[2]

- Achalasia (i.e. lack of the involuntary reflex in the esophagus after swallowing) appears to be a risk factor for both main types of esophageal cancer, at least in men, due to stagnation of trapped food and drink.[37]

- Plummer–Vinson syndrome (a rare disease that involves esophageal webs) is also a risk factor.[2]

- There is some evidence suggesting a possible causal association between

- There is an association between celiac disease and esophageal cancer. People with untreated celiac disease have a higher risk, but this risk decreases with time after diagnosis, probably due to the adoption of a gluten-free diet, which seems to have a protective role against development of malignancy in people with celiac disease. However, the delay in diagnosis and initiation of a gluten-free diet seems to increase the risk of malignancy. Moreover, in some cases the detection of celiac disease is due to the development of cancer, whose early symptoms are similar to some that may appear in celiac disease.[42]

Diagnosis

Clinical evaluation

Although an occlusive tumor may be suspected on a

Additional testing is needed to assess how much the cancer has spread (see

The location of the tumor is generally measured by the distance from the teeth. The esophagus (25 cm or 10 in long) is commonly divided into three parts for purposes of determining the location. Adenocarcinomas tend to occur nearer the stomach and squamous cell carcinomas nearer the throat, but either may arise anywhere in the esophagus.

-

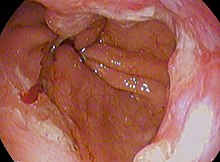

Endoscopic image ofBarrett esophagus– a frequent precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma

-

Endoscopy and radial endoscopic ultrasound images of a submucosal tumor in the central portion of the esophagus

-

Contrast CT scan showing an esophageal tumor (axial view)

-

Contrast CT scan showing an esophageal tumor (coronal view)

-

Esophageal cancer

-

histopathological appearance of an esophageal adenocarcinoma (dark blue – upper-left of image) and normal squamous epithelium (upper-right of image) at H&E staining

Types

Esophageal cancers are typically carcinomas that arise from the epithelium, or surface lining, of the esophagus. Most esophageal cancers fall into one of two classes: esophageal squamous-cell carcinomas (ESCC), which are similar to head and neck cancer in their appearance and association with tobacco and alcohol consumption—and esophageal adenocarcinomas (EAC), which are often associated with a history of GERD and Barrett's esophagus. A rule of thumb is that a cancer in the upper two-thirds is likely to be ESCC and one in the lower one-third EAC.

Rare histologic types of esophageal cancer include different variants of squamous-cell carcinoma, and non-epithelial tumors, such as leiomyosarcoma, malignant melanoma, rhabdomyosarcoma and lymphoma, among others.[47][48]

Staging

-

T1, T2, and T3 stages of esophageal cancer

-

Stage T4 esophageal cancer

-

Esophageal cancer with spread to lymph nodes

Prevention

Prevention includes stopping smoking or chewing tobacco.[2] Overcoming addiction to areca chewing in Asia is another promising strategy for the prevention of esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma.[4] The risk can also be reduced by maintaining a normal body weight.[51] According to a 2022 umbrella review, calcium intake could be associated with lower risk.[52]

According to the National Cancer Institute, "diets high in cruciferous (cabbage, broccoli/broccolini, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts) and green and yellow vegetables and fruits are associated with a decreased risk of esophageal cancer."[53] Dietary fiber is thought to be protective, especially against esophageal adenocarcinoma.[54] There is no evidence that vitamin supplements change the risk.[1]

Screening

People with Barrett's esophagus (a change in the cells lining the lower esophagus) are at much higher risk,[55] and may receive regular endoscopic screening for the early signs of cancer.[56] Because the benefit of screening for adenocarcinoma in people without symptoms is unclear,[2] it is not recommended in the United States.[1] Some areas of the world with high rates of squamous-carcinoma have screening programs.[2]

Management

Treatment is best managed by a multidisciplinary team covering the various

In general, treatment with a

Surgery

If the cancer has been diagnosed while still in an early stage, surgical treatment with a curative intention may be possible. Some small tumors that only involve the

The likely quality of life after treatment is a relevant factor when considering surgery.[63] Surgical outcomes are likely better in large centers where the procedures are frequently performed.[61] If the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, esophagectomy is nowadays not normally performed.[61][64]

Esophagectomy is the removal of a segment of the esophagus; as this shortens the length of the remaining esophagus, some other segment of the digestive tract is pulled up through the chest cavity and interposed. This is usually the stomach or part of the large intestine (colon) or jejunum. Reconnection of the stomach to a shortened esophagus is called an esophagogastric anastomosis.[61]

Esophagectomy can be performed using several methods. The choice of the surgical approach depends on the characteristics and location of the tumor, and the preference of the surgeon. Clear evidence from clinical trials for which approaches give the best outcomes in different circumstances is lacking.[61] A first decision, regarding the point of entry, is between a transhiatial and a transthoracic procedure. The more recent transhiatial approach avoids the need to open the chest; instead the surgeon enters the body through an incision in the lower abdomen and another in the neck. The lower part of the esophagus is freed from the surrounding tissues and cut away as necessary. The stomach is then pushed through the esophageal hiatus (the hole where the esophagus passes through the diaphragm) and is joined to the remaining upper part of the esophagus at the neck.[61]

The traditional transthoracic approach enters the body through the chest, and has a number of variations. The thoracoabdominal approach opens the abdominal and thoracic cavities together, the two-stage Ivor Lewis (also called Lewis–Tanner) approach involves an initial

If the person cannot swallow at all, an

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy

Chemotherapy depends on the tumor type, but tends to be cisplatin-based (or carboplatin or oxaliplatin) every three weeks with fluorouracil (5-FU) either continuously or every three weeks. In more recent studies, addition of epirubicin was better[clarification needed] than other comparable regimens in advanced nonresectable cancer.[65][medical citation needed] Chemotherapy may be given after surgery (adjuvant, i.e. to reduce risk of recurrence), before surgery (neoadjuvant) or if surgery is not possible; in this case, cisplatin and 5-FU are used. Ongoing trials compare various combinations of chemotherapy; the phase II/III REAL-2 trial – for example – compares four regimens containing epirubicin and either cisplatin or oxaliplatin, and either continuously infused fluorouracil or capecitabine.

Other approaches

Forms of endoscopic therapy have been used for stage 0 and I disease: endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)[66] and mucosal ablation using radiofrequency ablation, photodynamic therapy, Nd-YAG laser, or argon plasma coagulation.

Laser therapy is the use of high-intensity light to destroy tumor cells while affecting only the treated area. This is typically done if the cancer cannot be removed by surgery. The relief of a blockage can help with pain and difficulty swallowing. Photodynamic therapy, a type of laser therapy, involves the use of drugs that are absorbed by cancer cells; when exposed to a special light, the drugs become active and destroy the cancer cells.

-

Internal radiotherapy for esophageal cancer

-

Self-expandable metallic stents are sometimes used for palliative care

Follow-up

Patients are followed closely after a treatment regimen has been completed. Frequently, other treatments are used to improve symptoms and maximize nutrition.

Prognosis

In general, the prognosis of esophageal cancer is quite poor, because most patients present with advanced disease. By the time the first symptoms (such as difficulty swallowing) appear, the disease has already progressed. The overall five-year survival rate (5YSR) in the United States is around 15%, with most people dying within the first year of diagnosis.[67] The latest survival data for England and Wales (patients diagnosed during 2007) show that only one in ten people survives esophageal cancer for at least ten years.[68]

Individualized prognosis depends largely on stage. Those with cancer restricted entirely to the esophageal

Epidemiology

Esophageal cancer is the eighth-most frequently-diagnosed cancer worldwide,[2] and because of its poor prognosis, it is the sixth most-common cause of cancer-related deaths.[55] It caused about 400,000 deaths in 2012, accounting for about 5% of all cancer deaths (about 456,000 new cases were diagnosed, representing about 3% of all cancers).[2]

ESCC (esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma) comprises 60–70% of all cases of esophageal cancer worldwide, while EAC (esophageal adenocarcinoma) accounts for a further 20–30% (melanomas, leiomyosarcomas, carcinoids and lymphomas are less common types).

The worldwide

In Western countries, EAC has become the dominant form of the disease, following an increase in incidence over recent decades (in contrast to the incidence of ESCC, which has remained largely stable).

United States

In the United States, esophageal cancer is the seventh-leading cause of cancer-related deaths among males (making up 4% of the total).[74] The National Cancer Institute estimated that there were about 18,000 new cases and more than 15,000 deaths from esophageal cancer in 2013; the American Cancer Society estimated that during 2014, about 18,170 new esophageal cancer cases would be diagnosed, resulting in 15,450 deaths.[71][74]

The squamous-cell carcinoma type is more common among

United Kingdom

The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has risen considerably in the UK in recent decades.[16] Overall, esophageal cancer is the thirteenth most common cancer in the UK (around 8,300 people were diagnosed with the disease in 2011), and it is the sixth most common cause of cancer death (around 7,700 people died in 2012).[77]

Society and culture

Notable cases

Humphrey Bogart, actor, died of esophageal cancer in 1957, aged 57.

Actor John Thaw died of esophageal cancer in 2002, at the age of 60.

Christopher Hitchens, author and journalist, died of esophageal cancer in 2011, aged 62.[78]

Morrissey in October 2015 stated he has the disease and has described his experience when he first heard he had it.[79]

as Aku, died of esophageal cancer in 2006, aged 72.Robert Kardashian, attorney and businessman, died of esophageal cancer in 2003, aged 59.

Traci Braxton, singer and reality TV star, died of esophageal cancer in 2022, aged 50.

Ed Sullivan, host of the prominent self-titled television program The Ed Sullivan Show, died of esophageal cancer in 1974 at the age of 73

Research directions

The risk of esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma may be reduced in people using

The genomics of esophageal adenocarcinoma is being studied using Cancer genome sequencing. Esophageal adenocarcinoma is characterized by complex tumor genomes [81][82] with heterogeneity within the tumor micro-environment.[82]

See also

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-08373-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-09-19.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9.

- ^ PMID 22507220.

- ^ S2CID 14356684.

- ^ PMID 24078662.

- ^ a b "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Esophageal Cancer". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b "Esophageal Cancer Factsheet" (PDF). Global Cancer Observatory. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Even by those using the British English spelling "oesophagus"

- ISBN 978-0-7817-7617-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-09-25.

- ISBN 978-0-19-974797-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-31.

- S2CID 1541253.

- ^ PMID 14657432. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2014-07-14.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-174889-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-983012-1.

- ^ S2CID 13550805.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-5941-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-09-20.

- ISBN 978-1-55009-101-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-30.

- ^ PMID 20347291.

- ISBN 978-1-118-71325-9.

- S2CID 205103765.

- PMID 27318851. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2016-10-05. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ^ "Q&A on Monographs Volume 116: Coffee, maté, and very hot beverages" (PDF). www.iarc.fr. IARC / WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-935281-17-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-10.

- ^ PMID 21602001.

- ^ PMID 24092861.

- PMID 34099670.

- PMID 35429253.

- PMID 22898040.

- ^ S2CID 31598439.

- ^ PMID 23818335.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2014-08-12.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-8047-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-09-25.

- S2CID 207335139.

- S2CID 9504791.

- ^ "Tylosis with esophageal cancer". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – NIH. 18 January 2013. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-19-531117-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-25.

- PMID 23894436.

- PMID 22228147.

- S2CID 22862509.

- S2CID 21457534.

- PMID 26402826.

- PMID 26712189.

- PMID 19325056.

- PMID 18025508.

- S2CID 80059143.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-7982-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-25.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-6369-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-19.

- ^ Cancer arising at the junction between the esophagus and stomach is often classified as stomach cancer, as in ICD-10. See: "C16 - Malignant neoplasm of the stomach". ICD-10 Version: 2015. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- PMID 20176201.

- PMID 27557308.

- PMID 36041184.

- from the original on 2008-04-30.

- PMID 23815145.

- ^ PMID 24039351.

- PMID 24867396.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-118-71325-9.

- ^ Berry 2014, p. S292

- PMID 24671864.

- PMID 24885614.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4511-0545-2. Online edition, with updates to 2014

- PMID 24876933.

- S2CID 19933001.

- ^ Berry 2014, p. S293

- PMID 11956258.

- PMID 20703112.

- S2CID 6539230.

- ^ "Oesophageal cancer survival statistics". Cancer Research UK. 2015-05-15. Archived from the original on 2014-10-08.

- ^ "Esophageal Cancer Treatment | How We Treat Esophageal Cancer | KAIZEN Hospital". www.kaizenhospital.com. Archived from the original on 2021-01-21. Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- ^ from the original on 2013-05-17.

- ^ PMID 24834141.

- ^ PMID 25320104.

- PMID 21977849.

- ^ a b "Cancer Facts and Figures 2014" (PDF). American Cancer Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- PMID 19688596.

- ^ "Incidence and Mortality Rate Trends" (PDF). A Snapshot of Esophageal Cancer. National Cancer Institute. September 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-16. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ "Oesophageal cancer statistics". Cancer Research UK. 2015-05-14. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ "Christopher Hitchens' widow on his death: "God never came up"". CBS News. 7 September 2012. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ "Morrissey Talks Trump, Cancer Diagnosis, TSA Groping With Larry King". Rolling Stone. 2015-08-19. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- PMID 21539676.

- PMID 30718927.

- ^ PMID 37258531.

External links

- NCI esophageal cancer

- Cancer.Net: Esophageal Cancer

- Esophageal Cancer Archived 2009-07-12 at the Wayback Machine From Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach Archived 2009-05-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Oesophageal Cancer at Cancer Research UK

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network Archived 2019-03-31 at the Wayback Machine