Esophagus

| Esophagus | |

|---|---|

vagus | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | oesophagus |

| MeSH | D004947 |

| TA98 | A05.4.01.001 |

| TA2 | 2887 |

| FMA | 7131 |

| Anatomical terminology] | |

|

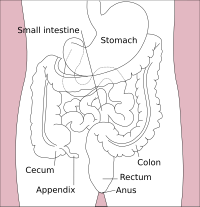

| Major parts of the |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

|---|

The esophagus (

The wall of the esophagus from the

The esophagus passes through the thoracic cavity into the diaphragm into the stomach.

The esophagus may be affected by

. Surgically, the esophagus is difficult to access in part due to its position between critical organs and directly between the sternum and spinal column.[2]Structure

The esophagus is one of the upper parts of the

Many

- Position

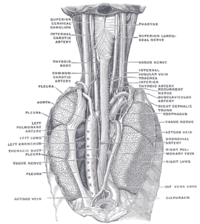

The upper esophagus lies at the back of the mediastinum behind the

The

- Constrictions

The esophagus has four points of constriction. When a corrosive substance, or a solid object is swallowed, it is most likely to lodge and damage one of these four points. These constrictions arise from particular structures that compress the esophagus. These constrictions are:[8]

- At the start of the esophagus, where the laryngopharynx joins the esophagus, behind the cricoid cartilage

- Where it is crossed on the front by the aortic arch in the superior mediastinum

- Where the esophagus is compressed by the left main bronchus in the posterior mediastinum

- The esophageal hiatus, where it passes through the diaphragm in the posterior mediastinum

Sphincters

The esophagus is surrounded at the top and bottom by two muscular rings, known respectively as the upper esophageal sphincter and the lower esophageal sphincter.[4] These sphincters act to close the esophagus when food is not being swallowed. The upper esophageal sphincter is an anatomical sphincter, which is formed by the lower portion of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor, also known as the cricopharyngeal sphincter due to its relation with cricoid cartilage of the larynx anteriorly. However, the lower esophageal sphincter is not an anatomical but rather a functional sphincter, meaning that it acts as a sphincter but does not have a distinct thickening like other sphincters.

The upper esophageal sphincter surrounds the upper part of the esophagus. It consists of

The lower esophageal sphincter, or gastroesophageal sphincter, surrounds the lower part of the esophagus at the junction between the esophagus and the stomach.

Nerve supply

The esophagus is innervated by the vagus nerve and the cervical and thoracic

Gastroesophageal junction

The gastroesophageal junction (also known as the esophagogastric junction) is the junction between the esophagus and the stomach, at the lower end of the esophagus.[13] The pink color of the esophageal mucosa contrasts to the deeper red of the gastric mucosa,[6][14] and the mucosal transition can be seen as an irregular zig-zag line, which is often called the z-line.[15] Histological examination reveals abrupt transition between the stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus and the simple columnar epithelium of the stomach.[16] Normally, the cardia of the stomach is immediately distal to the z-line[17] and the z-line coincides with the upper limit of the gastric folds of the cardia; however, when the anatomy of the mucosa is distorted in Barrett's esophagus the true gastroesophageal junction can be identified by the upper limit of the gastric folds rather than the mucosal transition.[18] The functional location of the lower oesophageal sphincter is generally situated about 3 cm (1+1⁄4 in) below the z-line.[6]

Microanatomy

|

| This article is one of a series on the |

| Gastrointestinal wall |

|---|

The human esophagus has a

The

Development

In early

The surrounded sac becomes the primitive gut. Sections of this gut begin to differentiate into the organs of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the esophagus,

Function

Swallowing

Food is

Reducing gastric reflux

The stomach produces

Gene and protein expression

About 20,000 protein-coding genes are expressed in human cells and nearly 70% of these genes are expressed in the normal esophagus.[24][25] Some 250 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the esophagus with less than 50 genes being highly specific. The corresponding esophagus-specific proteins are mainly involved in squamous differentiation such as keratins KRT13, KRT4 and KRT6C. Other specific proteins that help lubricate the inner surface of esophagus are mucins such as MUC21 and MUC22. Many genes with elevated expression are also shared with skin and other organs that are composed of squamous epithelia.[26]

Clinical significance

The main conditions affecting the esophagus are described here. For a more complete list, see esophageal disease.

Inflammation

Inflammation of the esophagus is known as

Barrett's esophagus

Prolonged esophagitis, particularly from gastric reflux, is one factor thought to play a role in the development of

Cancer

There are two main types of

In its early stages, esophageal cancer may not have any symptoms at all. When severe, esophageal cancer may eventually cause obstruction of the esophagus, making swallowing of any solid foods very difficult and causing weight loss. The progress of the cancer is

Varices

Esophageal varices often do not have symptoms until they rupture. A ruptured varix is considered a medical emergency because varices can bleed a lot. A bleeding varix may cause a person

Motility disorders

Several disorders affect the motility of food as it travels down the esophagus. This can cause difficult swallowing, called

Malformations

Two of the most common

Imaging

An

History

The word esophagus (

The first attempt at surgery on the esophagus focused in the neck, and was conducted in dogs by

The

Other animals

Vertebrates

- esophagus

- trachea

- tracheal lungs

- rudimentary left lung

- right lung

- heart

- liver

- stomach

- air sac

- gallbladder

- pancreas

- spleen

- intestine

- testicles

- kidneys

18. Small intestine: 19. Duodenum, 20. Jejunum

21–22. Right and left kidneys.

The front border of the liver has been lifted up (brown arrow).[38]

In tetrapods, the pharynx is much shorter, and the esophagus correspondingly longer, than in fish. In the majority of vertebrates, the esophagus is simply a connecting tube, but in some birds, which regurgitate components to feed their young, it is extended towards the lower end to form a crop for storing food before it enters the true stomach.[39][40] In ruminants, animals with four stomachs, a groove called the sulcus reticuli is often found in the esophagus, allowing milk to drain directly into the hind stomach, the abomasum.[41] In the horse the esophagus is about 1.2 to 1.5 m (4 to 5 ft) in length, and carries food to the stomach. A muscular ring, called the cardiac sphincter, connects the stomach to the esophagus. This sphincter is very well developed in horses. This and the oblique angle at which the esophagus connects to the stomach explains why horses cannot vomit.[42] The esophagus is also the area of the digestive tract where horses may have the condition known as choke.

The esophagus of snakes is remarkable for the distension it undergoes when swallowing prey.[43]

In most fish, the esophagus is extremely short, primarily due to the length of the pharynx (which is associated with the

In many vertebrates, the esophagus is lined by

The muscle of the esophagus in many mammals is initially striated but then becomes smooth muscle in the caudal third or so. In canines and ruminants, however, it is entirely striated to allow regurgitation to feed young (canines) or regurgitation to chew cud (ruminants). It is entirely smooth muscle in amphibians, reptiles and birds.[40]

Contrary to popular belief,[44] an adult human body would not be able to pass through the esophagus of a whale, which generally measures less than 10 cm (4 in) in diameter, although in larger baleen whales it may be up to 25 cm (10 in) when fully distended.[45]

Invertebrates

A structure with the same name is often found in invertebrates, including

In the cephalopods, the brain often surrounds the esophagus.[50]

See also

References

- ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Jacobo, Julia (24 November 2016). "Thanksgiving Tales From the Emergency Room". ABC News.

- ISBN 978-0-87893-695-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7020-3084-0.

- ^ doi:10.1038/gimo6 (inactive 31 January 2024).)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - ^ PMID 9347826.

- ISBN 978-0-443-06952-9.

- PMID 17074861.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 18923172.

- doi:10.1038/gimo13 (inactive 31 January 2024). Retrieved 24 May 2014.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - ISBN 978-0-683-23125-0.

- ISBN 978-1-55642-511-0.

- ISBN 978-1-4557-1144-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-2830-0.

- ISBN 978-0-07-177401-7.

- ISBN 978-0-7234-3252-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-7200-6.

- ISBN 978-4-431-68616-3.

- ISBN 978-0-443-06850-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-443-06811-9.

- ^ "Neuromuscular Anatomy of Esophagus and Lower Esophageal Sphincter - Motor Function of the Pharynx, Esophagus, and its Sphincters - NCBI Bookshelf". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 25 March 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "The human proteome in esophagus - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- S2CID 802377.

- PMID 25411189.

- S2CID 220976044.

- ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ISBN 978-0-87893-695-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-443-06583-5.

- PMID 16299066.

- S2CID 43782279.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Esophagus". Etymology Online. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-674-99640-3.

- ^ Bostock, John; Riley, Henry T.; Pliny the Elder (1855). The natural history of Pliny. London: H. G. Bohn. p. 64.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ISBN 978-0-674-99078-4.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ ISBN 978-0-387-30800-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-61714-7.

- PMID 21708724.

- ISBN 978-0-87605-606-6.

- S2CID 10921118.

- ^ Eveleth, Rose (20 February 2013). "Could a Whale Accidentally Swallow You? It Is Possible". Smithsonian. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-935848-47-2.

- S2CID 22477083.

- ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- .

- ^ Appleton C. C., Forbes A. T.& Demetriades N. T. (2009). "The occurrence, bionomics and potential impacts of the invasive freshwater snail Tarebia granifera (Lamarck, 1822) (Gastropoda: Thiaridae) in South Africa" Archived 2014-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. Zoologische Mededelingen 83.

- ISBN 978-3-7643-5076-5.