Ethiopia

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia የኢትዮጵያ ፌዴራላዊ ዴሞክራሲያዊ ሪፐብሊክ

( Amharic )Ye'ītiyop'iya Fēdēralawī Dēmokirasīyawī Rīpebilīki | ||

|---|---|---|

| Anthem: ወደፊት ገስግሺ ፣ ውድ እናት ኢትዮጵያ "Wedefīt Gesigishī Wid Inat ītiyop’iy" (English: " | ||

| ||

| Religion (2016[7]) |

| |

| Demonym(s) | Ethiopian | |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic[8] | |

| Sahle-Work Zewde | ||

| Abiy Ahmed | ||

| Temesgen Tiruneh | ||

| Tewodros Mihret | ||

| Legislature | Current constitution | 21 August 1995 |

+251 | ||

| ISO 3166 code | ET | |

| Internet TLD | .et | |

Ethiopia,[a] officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the Northeast, East and Southeast, Kenya to the South, South Sudan to the West, and Sudan to the Northwest. Ethiopia covers a land area of 1,112,000 square kilometres (472,000 sq. miles).[14] As of 2023[update], it is home to around 128 million inhabitants, making it the 13th-most populous country in the world, the 2nd-most populous in Africa after Nigeria, and the most populated landlocked country on Earth.[15][16] The national capital and largest city, Addis Ababa, lies several kilometres west of the East African Rift that splits the country into the African and Somali tectonic plates.[17]

From 1878 onwards, Emperor

Ethiopia is a

Etymology

The Greek name Αἰθιοπία (from Αἰθίοψ, "an Ethiopian") is a compound word, later explained as derived from the Greek words αἴθω and ὤψ (eithō "I burn" + ōps "face"). According to the Liddell-Scott Jones Greek-English Lexicon, the designation properly translates as burnt-face in noun form and red-brown in adjectival form.[33] The historian Herodotus used the appellation to denote those parts of Africa south of the Sahara that were then known within the Ecumene (habitable world).[34] The earliest mention of the term is found in the works of Homer, where it is used to refer to two people groups, one in Africa and one in the east from eastern Turkey to India.[35] This Greek name was borrowed into Amharic as ኢትዮጵያ, ʾĪtyōṗṗyā. An alternate theory suggests that Αἰθιοπία was derived from a native word ዕጣን (ʿəṭan, incense), of which Ethiopia was an important source.[citation needed]

In Greco-Roman epigraphs, Aethiopia was a specific toponym for ancient Nubia.[36] At least as early as c. 850,[37] the name Aethiopia also occurs in many translations of the Old Testament in allusion to Nubia. The ancient Hebrew texts identify Nubia instead as Kush.[38] However, in the New Testament, the Greek term Aithiops does occur, referring to a servant of the Kandake, the queen of Kush.[39]

Following the Hellenic and biblical traditions, the

In the 15th-century Ge'ez Book of Axum, the name is ascribed to a legendary individual called Ityopp'is. He was an extra-biblical son of Cush, son of Ham, said to have founded the city of Axum.[40]

In English, and generally outside of Ethiopia, the country was historically known as Abyssinia. This toponym was derived from the Latinized form of the ancient Habash.[41]

History

Prehistory

Several important finds have propelled Ethiopia and the surrounding region to the forefront of

Ethiopia is also considered one of the earliest sites of the emergence of anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens. The oldest of these local fossil finds, the Omo remains, were excavated in the southwestern Omo Kibish area and have been dated to the Middle Paleolithic, around 200,000 years ago.[46] Additionally, skeletons of Homo sapiens idaltu were found at a site in the Middle Awash valley. Dated to approximately 160,000 years ago, they may represent an extinct subspecies of Homo sapiens, or the immediate ancestors of anatomically modern humans.[47] Archaic Homo sapiens fossils excavated at the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco have since been dated to an earlier period, about 300,000 years ago,[48] while Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) from southern Ethiopia is the oldest anatomically modern Homo sapiens skeleton currently known (196 ± 5 kya).[49]

According to some linguists, the first

In 2019, archaeologists discovered a 30,000-year-old Middle Stone Age rock shelter at the Fincha Habera site in Bale Mountains at an elevation of 3,469 metres (11,381 feet) above sea level. At this high altitude, humans are susceptible both to hypoxia and to extreme weather. According to a study published in the journal Science, this dwelling is proof of the earliest permanent human occupation at high altitude yet discovered. Thousands of animal bones, hundreds of stone tools, and ancient fireplaces were discovered, revealing a diet that featured giant mole rats.[55][56][57][58][59][60][61]

Evidence of some of the earliest known stone-tipped projectile weapons (a characteristic tool of Homo sapiens), the stone tips of javelins or throwing spears, were discovered in 2013 at the Ethiopian site of Gademotta, which date to around 279,000 years ago.[62] In 2019, additional Middle Stone Age projectile weapons were found at Aduma, dated 100,000–80,000 years ago, in the form of points considered likely to belong to darts delivered by spear throwers.[63]

Antiquity

In 980 BC, Dʿmt was established in present-day Eritrea and the Tigray Region of Ethiopia and is widely believed to be the successor state to Punt. This polity's capital was located at Yeha in what is now northern Ethiopia. Most modern historians consider this civilization to be a native Ethiopian one, although in earlier times many suggested it was Sabaean-influenced because of the latter's hegemony of the Red Sea.[64]

Other scholars regard Dʿmt as the result of a union of Afroasiatic-speaking cultures of the Cushitic and Semitic branches; namely, local

After the fall of Dʿmt during the 4th century BC, the Ethiopian plateau came to be dominated by smaller successor kingdoms. In the 1st century AD, the Kingdom of Aksum emerged in what is now Tigray Region and Eritrea. According to the medieval Book of Axum, the kingdom's first capital, Mazaber, was built by Itiyopis, son of Cush.[40] Aksum would later at times extend its rule into Yemen on the other side of the Red Sea.[67] The Persian prophet Mani listed Axum with Rome, Persia, and China as one of the four great powers of his era, during the 3rd century.[68] It is also believed that there was a connection between Egyptian and Ethiopian churches. There is diminutive evidence that the Aksumites were associated with the Queen of Sheba, via their royal inscription.[69]

Around 316 AD, Frumentius and his brother Edesius from Tyre accompanied their uncle on a voyage to Ethiopia. When the vessel stopped at a Red Sea port, the natives killed all the travellers except the two brothers, who were taken to the court as slaves. They were given positions of trust by the monarch, and they converted members of the royal court to Christianity. Frumentius became the first bishop of Aksum.[70] A coin dated to 324 shows that Ethiopia was the second country to officially adopt Christianity (after Armenia did so in 301), although the religion may have been at first confined to court circles; it was the first major power to do so. The Aksumites were accustomed to the Greco-Roman sphere of influence, but embarked on significant cultural ties and trade connections between the Indian subcontinent and the Roman Empire via the Silk Road, primarily exporting ivory, tortoise shell, gold and emeralds, and importing silk and spices.[69][71]

Middle Ages

The kingdom adopted the name "Ethiopia" during the reign of

The Ethiopian Empire initiated territorial expansion under the leadership of Amda Seyon I. He launched campaigns against his Muslim adversaries to the east, resulting in a significant shift in the balance of power in favor of the Christians for the next two centuries. After Amda Seyon's successful eastern campaigns, most of the Muslim principalities in the Horn of Africa came under the suzerainty of the Ethiopian Empire. Stretching from Gojjam to the Somali Coast in Zelia.[76] Among these Muslim entities was the Sultanate of Ifat. During the reign of Emperor Zara Yaqob, the Ethiopian Empire reached its pinnacle. His rule was marked by the consolidation of territorial acquisitions from earlier rulers, the oversight of the construction of numerous churches and monasteries, the active promotion of literature and art, and the strengthening of central imperial authority.[77][78][79] Ifat's successor, the Adal Sultanate,[80] tried to conquer Ethiopia during the Ethiopian–Adal War, but was ultimately defeated at the 1543 Battle of Wayna Daga.[81]

By the 16th century, an influx of migration by ethnic

Ethiopia saw major diplomatic contact with Portugal from the 17th century, mainly related to religion. Beginning in 1555,[86] Portuguese Jesuits attempted to develop Roman Catholicism as the state religion. After several failures, they sent several missionaries in 1603, including the most influential, Spanish Jesuit Pedro Paez.[87] Under Emperor Susenyos I, Roman Catholicism became the state religion of the Ethiopian Empire in 1622.[88] This decision caused an uprising by the Orthodox populace.[89]

Early Modern Period (1632–1855)

In 1632, Emperor

Gondar's power declined after the death of Iyasu I in 1706. Following Iyasu II's death in 1755, Empress Mentewab brought her brother, Ras Wolde Leul, to Gondar, making him Ras Bitwaded. This led to regnal conflict between Mentewab's Quaregnoch and the Wollo group led by Wubit. In 1767, Ras Mikael Sehul, a regent in Tigray Province, seized Gondar, killing the child Iyoas I in 1769, the reigning emperor, and installed 70-year-old Yohannes II.[93]

Between 1769 and 1855, Ethiopia witnessed the Zemene Mesafint or "Age of Princes," a period of isolation. Emperors became figureheads, controlled by regional lords and noblemen like Ras Mikael Sehul, Ras Wolde Selassie of Tigray, and by the Yejju Oromo dynasty of the Wara Sheh, including Ras Gugsa of Yejju. Before the Zemene Mesafint, Emperor Iyoas I had introduced the Oromo language (Afaan Oromo) at court, replacing Amharic.[94][95]

Age of Imperialism (1855–1916)

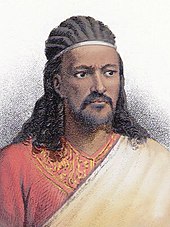

Ethiopian isolationism ended following a British mission that concluded with an alliance between the two nations, but it was not until 1855 that the Amhara kingdoms of northern Ethiopia (Gondar, Gojjam, and Shewa) were briefly united after the power of the emperor was restored beginning with the reign of Tewodros II.[96][97] Tewodros II began a process of consolidation, centralisation, and state-building that would be continued by succeeding emperors. This process reduced the power of regional rulers, restructured the empire's administration, and created a professional army. These changes created the basis for establishing the effective sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Ethiopian state.[98] In 1875 and 1876, Ottoman and Egyptian forces, accompanied by many European and American advisors, twice invaded Abyssinia but were initially defeated.[99] From 1885 to 1889 (under Yohannes IV), Ethiopia joined the Mahdist War allied to Britain, Turkey, and Egypt against the Sudanese Mahdist State. In 1887, Menelik II, king of Shewa, invaded the Emirate of Harar after his victory at the Battle of Chelenqo.[100] On 10 March 1889, Yohannes IV was killed by the Sudanese Khalifah Abdullah's army whilst leading his army in the Battle of Gallabat.[101]

Ethiopia, in roughly its current form, began under the reign of Menelik II, who was Emperor from 1889 until his death in 1913. From his base in the central province of Shewa, Menelik set out to annex territories to the south, east, and west[102] — areas inhabited by the Oromo, Sidama, Gurage, Welayta, and other peoples.[103] He achieved this with the help of Ras Gobana Dacche's Shewan Oromo militia, which occupied lands that had not been held since Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi's war, as well as other areas that had never been under Ethiopian rule.[104]

For his leadership, despite opposition from more traditional elements of society, Menelik II was heralded as a national hero. He had signed the

Haile Selassie I era (1916–1974)

The early 20th century was marked by the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie (Ras Tafari). He came to power after Lij Iyasu was deposed, and undertook a nationwide modernization campaign from 1916 when he was made a Ras and Regent (Inderase) for the Empress Regnant Zewditu, and became the de facto ruler of the Ethiopian Empire. Following Zewditu's death, on 2 November 1930, he succeeded her as emperor.[108] In 1931, Haile Selassie endowed Ethiopia with its first-ever Constitution in emulation of Imperial Japan's 1890 Constitution.[109] The independence of Ethiopia was interrupted by the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, beginning when it was invaded by Fascist Italy in early October 1935, and by subsequent Italian rule of the country (1936–1941) after Italian victory in the war.[110] Italy, however never managed to secure the country, due to resistance from the Arbegnoch, making Ethiopia and Liberia the only African nations to never be colonized.[111] Following the entry of Italy into World War II, British Empire forces, together with the Arbegnoch, liberated Ethiopia in the course of the East African campaign in 1941. The country was placed under British military administration, and then Ethiopia's full sovereignty was restored with the signing of the Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement in December 1944.[112]

On 24 October 1945, Ethiopia became a founding member of the United Nations. In 1952, Haile Selassie orchestrated a federation with Eritrea. He dissolved this in 1962 and annexed Eritrea, resulting in the Eritrean War of Independence.[citation needed] Haile Selassie also played a leading role in the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU).[113] Opinion within Ethiopia turned against Haile Selassie, owing to the worldwide 1973 oil crisis causing a sharp increase in gasoline prices starting on 13 February 1974, leading to student and worker protests.[114] The feudal oligarchical cabinet of Aklilu Habte-Wold was toppled, and a new government was formed with Endelkachew Makonnen serving as Prime Minister.[115]

Derg era (1974–1991)

Haile Selassie's rule ended on 12 September 1974, when he was

After a power struggle in 1977,

In 1976–78, up to 500,000 were killed as a result of the Red Terror,[124] a violent political repression campaign by the Derg against various opposition groups.[125][126][127] In 1987, the Derg dissolved itself and established the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE) upon the adoption of the 1987 Constitution of Ethiopia.[128] A 1983–85 famine affected around 8 million people, resulting in 1 million dead. Insurrections against authoritarian rule sprang up, particularly in the northern regions of Eritrea and Tigray. The Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) merged with other ethnically based opposition movements in 1989, to form the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF).[129]

The collapse of Marxism–Leninism during the revolutions of 1989 coincided with the Soviet Union stopping aid to Ethiopia altogether in 1990.[130][131][132] EPRDF forces advanced on Addis Ababa in May 1991, and Mengistu fled the country and was granted asylum in Zimbabwe.[133][134]

Federal Democratic Republic (1991–present)

In July 1991, the EPRDF convened a National Conference to establish the Transitional Government of Ethiopia composed of an 87-member Council of Representatives and guided by a national charter that functioned as a transitional constitution.[135] In 1994, a new constitution was written that established a parliamentary republic with a bicameral legislature and a judicial system.[136]

In April 1993, Eritrea gained independence from Ethiopia after a national referendum.[137] In May 1998, a border dispute with Eritrea led to the Eritrean–Ethiopian War, which lasted until June 2000 and cost both countries an estimated $1 million a day.[138] This had a negative effect on Ethiopia's economy, and a border conflict between the two countries would continue until 2018.[139][140] As of 2018, further civil war in Ethiopia continues, mainly due to destabilization of the country.

Ethnic violence rose during the late 2010s and early 2020s,[141][142] with various clashes and conflicts leading to millions of Ethiopians being displaced.[143][144][145]

The federal government decided that elections for 2020 (later being rescheduled to 2021) be cancelled, due to health and safety concerns about COVID-19.[146] The Tigray Region's TPLF opposed this, and proceeded to hold elections anyway on 9 September 2020.[147][148] Relations between the federal government and Tigray deteriorated rapidly,[149] and in November 2020, Ethiopia began a military offensive in Tigray in response to attacks on army units stationed there, marking the beginning of the Tigray War.[150][151] By March 2022, as many as 500,000 people had died as a result of violence and famine.[152][153][154] After a number of peace and mediation proposals in the intervening years, Ethiopia and the Tigrayan rebel forces agreed to a cessation of hostilities on 2 November 2022.[155]

Government and politics

Government

Ethiopia is a

The Ethiopian judiciary consists of dual system with two court structures: the federal and state courts. The FDRE Constitution vested federal judicial authority to the Federal Supreme Court which can overturn and review decisions of subordinate federal courts; itself has regular division assigned for fundamental errors of law. In addition, the Supreme Court can perform circuit hearings in established five states at any states of federal levels or "area designated for its jurisdiction" if deemed "necessary for the efficient rendering of justice".[156][157]

The Federal Supreme Proclamation granted three subject matter principles: laws, parties and place to federal court jurisdiction, first "cases arising under the

On the basis of Article 78 of the 1994 Ethiopian Constitution, the judiciary is completely independent of the executive and the legislature.[159] To ensure this, the President and Vice President of the Supreme Court are appointed by Parliament on the nomination of Prime Minister. Once elected, the executive power has no authority to remove them from office. Other judges are nominated by the Federal Judicial Administration Council (FJAC) on the basis of transparent criteria and the Prime Minister's recommendation for appointment in the HoPR. In all cases, judges cannot be removed from their duty unless they retired, violated disciplinary rules, gross incompatibility, or inefficiency to unfit due to ill health. Contrary, the majority vote of HoPR have the right to sanction removal in federal judiciary level or state council in cases of state judges.[160] In 2015, the realities of this provision were questioned in a report prepared by Freedom House.[161]

Politics

Post-1995, Ethiopia's politics has been liberalized which promotes all-encompassing reforms to the country. Today, its economy is based on mixed, market-oriented principles.[160] Ethiopia has eleven semi-autonomous administrative regions that have the power to raise and spend their own revenues.[citation needed]

The

Meles died on 20 August 2012 in Brussels, where he was being treated for an unspecified illness.

According to the

Accompanied by pervasive internal and intercommunal conflicts in the 21st century, the Ethiopian government resorted to authoritarian structure, severing democratic and human rights.[174] Freedom House, who has worked on Ethiopia since 2008, indicates that Ethiopia is "Not Free" state due to very poor fundamental rights (political and civil liberties) recorded in both EPRDF and Prosperity Party regimes.[175][176] Under Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia is experiencing democratic backsliding since 2019 marked by turbulent period of internal conflict, jailing opposition group members and limit media freedom.[177][178][179]

Foreign relations

Ethiopia was historically a

Today, Ethiopia maintains strong relations with

Ethiopia's foreign relations with both

Ethiopia is one of the African countries that was a founding member of

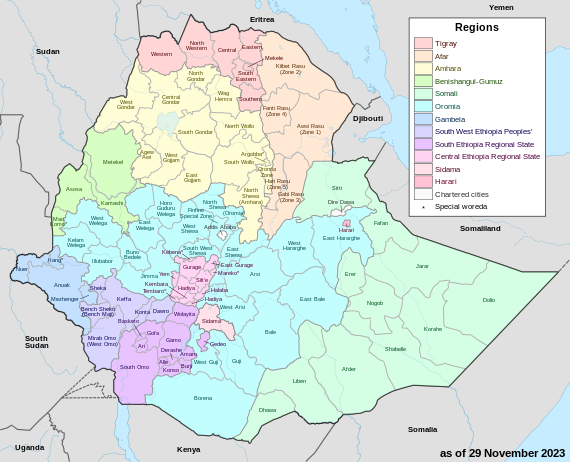

Administrative divisions

Ethiopia is administratively divided into four levels: regions, zones, woredas (districts) and kebele (wards).[192][193] The country comprises 12 regions and two city administrations under these regions, plenty of zones, woredas and neighbourhood administration: kebeles. The two federal-level city administrations are Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa.[194]

Military

The Ethiopian army's origins and military traditions date back to the earliest history of Ethiopia. Due to Ethiopia's location between the Middle East and Africa, it has long been in the middle of Eastern and Western politics and has been subject to foreign invasions. In 1579, the Ottoman Empire's attempt to expand from a coastal base at Massawa during the Ottoman conquest of Habesh was defeated.[195] The Army of the Ethiopian Empire was also able to defeat the Egyptians in 1876 at Gura, led by Ethiopian Emperor Yohannes IV.[196]

Economy

Ethiopia registered the fastest economic growth under Meles Zenawi's administration.[197] According to the

In 2008 and 2011, Ethiopia's growth performance and considerable development gains were challenged by high inflation and a difficult balance of payments situation. Inflation surged to 40% in August 2011 because of loose monetary policy, large civil service wage increase in early 2011, and high food prices.[201]

In spite of fast growth in recent years, GDP per capita is one of the lowest in the world, and the economy faces a number of serious structural problems. However, with a focused investment in public infrastructure and industrial parks, Ethiopia's economy is addressing its structural problems to become a hub for light manufacturing in Africa.[202] In 2019 a law was passed allowing expatriate Ethiopians to invest in Ethiopia's financial service industry.[203]

The Ethiopian constitution specifies that rights to own land belong only to "the state and the people", but citizens may lease land for up to 99 years, but are unable to mortgage or sell. Renting out land for a maximum of twenty years is allowed and this is expected to ensure that land goes to the most productive user. Land distribution and administration is considered an area where corruption is institutionalized, and facilitation payments as well as bribes are often demanded when dealing with land-related issues.[204] As there is no land ownership, infrastructural projects are most often simply done without asking the land users, which then end up being displaced and without a home or land. A lot of anger and distrust sometimes results in public protests. In addition, agricultural productivity remains low, and frequent droughts still beset the country, also leading to internal displacement.[205]

Energy and hydropower

Ethiopia has 14 major rivers flowing from its highlands, including the Nile. It has the largest water reserves in Africa. As of 2012[update], hydroelectric plants represented around 88.2% of the total installed electricity generating capacity.

The remaining electrical power was generated from fossil fuels (8.3%) and renewable sources (3.6%).

The electrification rate for the total population in 2016 was 42%, with 85% coverage in urban areas and 26% coverage in rural areas. As of 2016[update], total electricity production was 11.15 TW⋅h and consumption was 9.062 TW⋅h. There were 0.166 TW⋅h of electricity exported, 0 kW⋅h imported, and 2.784 GW of installed generating capacity.[17] Ethiopia delivers roughly 81% of water volume to the Nile through the river basins of the Blue Nile, Sobat River and Atbara. In 1959, Egypt and Sudan signed a bilateral treaty, the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement, which gave both countries exclusive maritime rights over the Nile waters. Ever since, Egypt has discouraged almost all projects in Ethiopia that sought to use the local Nile tributaries. This had the effect of discouraging external financing of hydropower and irrigation projects in western Ethiopia, thereby impeding water resource-based economic development projects. However, Ethiopia is in the process of constructing a large 6,450 MW hydroelectric dam on the Blue Nile river. When completed, this Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is slated to be the largest hydroelectric power station in Africa.[206] The Gibe III hydroelectric project is so far the largest in the country with an installed capacity of 1,870 MW. For the year 2017–18 (2010 E.C) this hydroelectric dam generated 4,900 GW⋅h.[207]

Agriculture

References

Citations

- ^ "Ethiopia to Add 4 more Official Languages to Foster Unity". Ventures Africa. 4 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ "Ethiopia is adding four more official languages to Amharic as political instability mounts". Nazret. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ a b Shaban A. "One to five: Ethiopia gets four new federal working languages". Africa News. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopian Constitution". www.africa.upenn.edu.

- ^ "Table 2.2 Percentage distribution of major ethnic groups: 2007" (PDF). Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results. Population Census Commission. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ CSA. 13 July 2010. Archived from the originalon 8 February 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ^ "Ethiopia- The World Factbook". www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ "Zenawism as ethnic-federalism" (PDF).

- ^ "Overview About Ethiopia - Embassy of Ethiopia". 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Ethiopia Population (Live)". worldometer.info. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Ethiopia)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "Gini Index coefficient". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Ethiopia EO (30 July 2023). "About Ethiopia". Embassy Of Ethiopia Washington.

- ^ "Population Projections for Ethiopia 2007–2037". www.csa.gov.et. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopia". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 September 2022. (Archived 2022 edition.)

- ^ a b c d "Ethiopia". The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- OCLC 819506475.

- .

- S2CID 53541133.

- ^ "Humans Moved From Africa Across Globe, DNA Study Says". Bloomberg News. 21 February 2008. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ Kaplan K (21 February 2008). "Around the world from Addis Ababa". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-7591-0466-2.

- S2CID 162029676.

- JSTOR 1771876.

- ^ "Ethnicity and Power in Ethiopia" (PDF). 12 April 2022.

- ^ BBC Staff (3 November 2020). "Ethiopia attack: Dozens 'rounded up and killed' in Oromia state". BBC. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ "Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Ethiopia formally join BRICS". Daily News Egypt. 1 January 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ "5 reasons why Ethiopia could be the next global economy to watch". World Economic Forum. 6 September 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Africa S (29 August 2020). "Ethiopia Can Be Africa's Next Superpower". SomTribune. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "Overview". World Bank. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Agriculture in Ethiopia: data shows for a large part Agriculture still retained its majority share of the economy". The Low Ethiopian Reports. 16 June 2022.

- ^ Liddell HG, Scott R. "Aithiops". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- Perseus Project.

- ^ Homer, Odyssey 1.22–4.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8147-6066-6.

- ^ Etymologicum Genuinum s.v. Αἰθιοπία; see also Aethiopia

- ^ Cp. Ezekiel 29:10

- ^ Acts 8:27

- ^ a b Africa Geoscience Review, Volume 10. Rock View International. 2003. p. 366. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ Schoff WH (1912). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: travel and trade in the Indian Ocean. Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 62. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ Ansari A (7 October 2009). "Oldest human skeleton offers new clues to evolution". CNN.com/technology. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Mother of man – 3.2 million years ago". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-307-39640-2.

- ^ "Institute of Human Origins: Lucy's Story". 15 June 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- S2CID 1454595.

- S2CID 4432091.

- . Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- PMID 28552208.

- S2CID 163491760.

- S2CID 13350469.

- ISBN 978-0-7591-0466-2.

- ISBN 978-3-11-042606-9.

- ISBN 978-0-262-54218-0.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Katz B. "Archaeologists Uncover Evidence of an Ancient High-Altitude Human Dwelling". Smithsonian. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Smith KN (9 August 2019). "The first people to live at high elevations snacked on giant mole rats". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Charles Q. Choi (9 August 2019). "Earliest Evidence of Human Mountaineers Found in Ethiopia". livescience.com. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Dvorsky G (9 August 2019). "This Rock Shelter in Ethiopia May Be the Earliest Evidence of Humans Living in the Mountains". Gizmodo. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Earliest evidence of high-altitude living found in Ethiopia". UPI. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- S2CID 199505803.

- PMID 24236011.

- PMID 31071181.

- ^ a b c d Munro-Hay, p. 57

- ^ Tamrat, Taddesse (1972) Church and State in Ethiopia: 1270–1527. London: Oxford University Press, pp. 5–13.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert (ed.) (2005) Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, "Ge'ez". Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, p. 732.

- ISBN 978-0-7141-2763-7.

- ^ Munro-Hay, p. 13

- ^ a b "Solomonic Descent in Ethiopian History". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-313-32273-0.

- ^ The British Museum, The CarAf Centre. "The wealth of Africa – The kingdom of Aksum – Teachers' notes" (PDF). BritishMuseum.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2019.

- ^ Karl W. Butzer, "Rise and Fall of Axum, Ethiopia: A Geo-Archaeological Interpretation", American Antiquity 46, (July 1981), p. 495

- ^ "Kingdom of Abyssinia". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "A New History Changes the Balance of Power Between Ethiopia and Medieval Europe". 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Ethiopia The Zagwe Dynasty – Flags, Maps, Economy, History, Climate, Natural Resources, Current Issues, International Agreements, Population, Social Statistics, Political System". photius.com. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ISBN 978-3-515-03204-9.

- ISBN 978-0-520-06698-4.

- ISBN 978-1-136-28090-0.

- ^ Connel & Killion 2011, p. 160.

- ISBN 978-3-643-90332-7.

- ^ Fortunes of Africa: A 5,000 Year History of Wealth, Greed and Endeavour By Martin Meredith, In the Land of Prestor John, chapter 11

- OCLC 962017017.

- ^ Pankhurst 1997, p. 301.

- ^ "Ethiopia: The Trials of the Christian Kingdom and the Decline of Imperial Power ~a HREF="/et_00_00.html#et_01_02"". memory.loc.gov. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ "Oromo: Migration and Expansion: Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries".

- ISBN 978-3-447-05892-6.

- ^ "Latin Letters of Jesuits -Wendy Laura Belcher". wendybelcher.com. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-316-51519-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7922-3695-5.

- ^ See Solomon Getamun, History of the City of Gondar (Africa World Press, 2005), pp.1–4

- ^ Getamun, City of Gondar, p. 5

- ^ Pankhurst, Economic History of Ethiopia (Addis Ababa: Haile Selassie University Press, 1968), pp. 297f

- ^ "Gondar Period". ethiopianhistory.com. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1967). The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 139–143.

- ^ "Political Program of the Oromo People's Congress (OPC)". Gargaaraoromopc.org. 23 April 1996. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-317-45158-7.

- ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4.

- ISBN 978-1-58826-340-7.[dead link]

- ^ The Egyptians in Abyssinia Archived 26 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Vislardica.com. Retrieved on 3 March 2012.

- JSTOR 41967469.

- OCLC 14069361.

- JSTOR 3993156.

- ^ a b International Crisis Group, "Ethnic Federalism and its Discontents". Issue 153 of ICG Africa report (4 September 2009) p. 2; Italy lost over 4,600 nationals in this battle.

- JSTOR 216612.

- ISBN 1-56000-992-6pp. 13–14

- ^ "Famine Hunger stalks Ethiopia once again – and aid groups fear the worst". Time. 21 December 1987.

- PMID 5326887.

- ^ Broich T (2017). "U.S. and Soviet Foreign Aid during the Cold War – A Case Study of Ethiopia". The United Nations University – Maastricht Economic and Social Research Institute on Innovation and Technology (UNU-MERIT).

- ^ Asnake Kefale, Tomasz Kamusella and Christopher Van der Beken. 2021. Eurasian Empires as Blueprints for Ethiopia: From Ethnolinguistic Nation-State to Multiethnic Federation. London: Routledge, pp 23–34.

- ^ Clapham, Christopher (2005) "Ḫaylä Śəllase" in Siegbert von Uhlig, ed., Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha. Wiesbaden:Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 1062–63.

- ISBN 0-631-22493-9.

- ^ Clapham, "Ḫaylä Śəllase", Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, p. 1063.

- ^ "(1963) Haile Selassie, "Towards African Unity"". BlackPast.org. 7 August 2009.

- ^ Valdes Vivo, p. 115.

- ^ Valdes Vivo, p. 21.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- OCLC 25316141.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ISBN 978-3-8258-9535-8.

- ^ "The Mengistu Regime and Its Impact". Library of Congress.

- ^ Oberdorfer D (March 1978). "The Superpowers and the Ogaden War". The Washington Post.

- ^ "US admits helping Mengistu escape". BBC. 22 December 1999. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ The Black Book of Communism, pp. 687–95

- ^ Ottaway DB (21 March 1979). "Addis Ababa Emerges From a Long, Bloody War". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Katz DR (21 September 1978). "Ethiopia After the Revolution: Vultures in the Land of Sheba". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Asnake Kefale, Tomasz Kamusella and Christopher Van der Beken. 2021. Eurasian Empires as Blueprints for Ethiopia: From Ethnolinguistic Nation-State to Multiethnic Federation. London: Routledge, pp 35–43

- ISBN 978-1-4408-3052-5.

- ^ "Foreign Policy". Library of Congress – American Memory: Remaining Collections.

- ^ Crowell Anderson-Jaquest T (May 2002). "Restructuring the Soviet–Ethiopian Relationship: A Csse Study in Asymmetric Exchange" (PDF). London School of Economics and Political Science.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Mengistu Haile Mariam Interview (1990), retrieved 17 June 2021

- ^ Tessema S (November 2017). "ADDIS ABABA". Anadolu Agency.

- ^ "Why a photo of Mengistu has proved so controversial". BBC News. August 2018.

- ^ Lyons 1996, pp. 121–23.

- ^ a b "Article 5" (PDF). Ethiopian Constitution. WIPO. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Will arms ban slow war?". BBC News. 18 May 2000. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "War 'devastated' Ethiopian economy". BBC News. 7 August 2001. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Ethiopia and Eritrea declare end of war". BBC News. 9 July 2018.

- ^ "At least 23 die in weekend of Ethiopia ethnic violence". The Daily Star. 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ Ahmed H, Goldstein J (24 September 2018). "Thousands Are Arrested in Ethiopia After Ethnic Violence". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ "Ethnic violence displaces hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians". irinnews.com. 8 November 2017.

- ^ "12 killed in latest attack in western Ethiopia". News24. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Fano Will Not Lay Down Arms If Demands Are Not Met: Chairman, retrieved 28 March 2020

- ^ "Ethiopian parliament allows PM Abiy to stay in office beyond term". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopia's Tigray region defies PM Abiy with 'illegal' election". France 24. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopia's Tigray region holds vote, defying Abiy's federal gov't". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopia Tigray crisis: Rockets hit outskirts of Eritrea capital". BBC News. 15 November 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopia Tigray crisis: Rights commission to investigate 'mass killings'". BBC News. 14 November 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopia: Tigray leader confirms bombing Eritrean capital". Al-Jazeera. 15 November 2020.

- ^ "Tigray war has seen up to half a million dead from violence and starvation, say researchers". The Globe and Mail. 15 March 2022.

- ^ "The World's Deadliest War Isn't in Ukraine, But in Ethiopia". The Washington Post. 23 March 2022.

- ^ Chothia F, Bekit T (19 October 2022). "Ethiopia civil war: Hyenas scavenge on corpses as Tigray forces retreat". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022.

- ^ Winning A, Cocks T (2 November 2022). "Parties in Ethiopia conflict agree to cease hostilities". Reuters.

- ^ See Federal High Court Establishment Proclamation No.322/2003. Federal High Courts have been placed in the following states: Afar, Benshngul/Gumuz, Gambela, Somali, and SNNPR.

- ^ Federal Courts Proclamation 25/1996, as amended by Federal Courts (Amendment) Proclamation 138/1998, Federal Courts (Amendment) Proclamation 254/2001, Federal Courts (Amendment) Proclamation 321/2003, and Federal Courts Proclamation (Reamendment) Proclamation 454/2005 (Federal Courts Proclamation), Article 24(3).

- ^ Federal Courts Proclamation 25/1996, Article 3.

- ^ "Constitution of Ethiopia – 8 December 1994". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008.

- ^ a b Ethiopia – Country Governance Profile EN.pdf. OSGE and OREB. March 2009. p. 14.

- ^ "Ethiopia | Country report | Freedom in the World | 2015". freedomhouse.org. 21 January 2015. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Lyons 1996, p. 142.

- ^ "President expelled from ruling party". IRIN. 25 June 2001. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ "Map of Freedom 2007". Freedom House. 2007. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2007.

- ^ "Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles has died: state television". Reuters. 21 August 2012.

- ^ Lough R (22 August 2012). "Ethiopia acting PM to remain at helm until 2015". Reuters.

- ^ Malone B (27 May 2015). "Profile: Ethiopia's 'placeholder' PM quietly holds on". aljazeera.com. Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ Maasho A (8 August 2016). "At least 33 protesters killed in Ethiopia's Oromiya region: opposition". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "Ethiopia declares state of emergency". BBC News. 16 February 2018.

- ^ AfricaNews. "Ethiopia declares 6 months state of emergency over Oromia protests | Africanews". Africanews. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ "Ethiopian Prime Minister wins the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize". CNN News. 16 October 2019.

- ^ The Economist Intelligence Unit's Index of Democracy 2010. (PDF). Retrieved on 3 March 2012.

- ^ The Economist Intelligence Unit's Index of Democracy 2010. (PDF). p.17. Retrieved on 3 March 2012.

- JSTOR 41931114.

- ^ "Ethiopia: Country Profile". Freedom House. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Failure to Stand for Democracy in Ethiopia Has Weakened Democracy Worldwide". The Institute for Peace and Diplomacy - l’Institut pour la paix et la diplomatie. 3 November 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Ethiopia: Freedom in the World 2021 Country Report". Freedom House. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Velasco G (1 April 2022). "The Ethiopia of Abiy Ahmed and the Pending Transition". IDEES. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Gedamu Y (16 June 2020). "Abiy put Ethiopia on the road to democracy: but major obstacles still stand in the way". The Conversation. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Land of Punt". ethiopianhistory.com. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ The political history of the Ethiopian community, and their struggle for ownership of this small monastery, is retold in Chris Proutky, Empress Taytu and Menelik II (Trenton: The Red Sea Press, 1986), pp. 247–256

- ^ Although Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, second edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), believes that the Suez Canal brought strategic value to the Red Sea region (p. 73), Sven Rubenson, The Survival of Ethiopian Independence (Hollywood: Tsehai,1991) argues that only with the Mahdi War did the United Kingdom interest themselves once again in Ethiopia (pp. 283ff).

- ^ "Ethiopia – Agoa.info – African Growth and Opportunity Act". agoa.info. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Gregory W. "Obama Becomes First Sitting U.S. President To Visit Ethiopia". National Public Radio. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Onyulo T (26 July 2015). "Obama visit highlights Ethiopia's role in fighting Islamist terrorists". USA Today.

- ^ Walsh D (9 February 2020). "For Thousands of Years, Egypt Controlled the Nile. A New Dam Threatens That". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 February 2020.

- ^ "An Egyptian cyber attack on Ethiopia by hackers is the latest strike over the Grand Dam". Quartz. 27 June 2020.

- ^ "Row over Africa's largest dam in danger of escalating, warn scientists". Nature. 15 July 2020.

- ^ "Who Owns the Nile? Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia's History-Changing Dam". Origins. 15 March 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ "Are Egypt and Ethiopia heading for a water war?". The Week. 8 July 2020.

- ^ "The United Nations in Ethiopia | United Nations in Ethiopia". ethiopia.un.org. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- JSTOR 26586251.

- ^ "Ethiopia Political Map and Regions | Mappr". www.mappr.co. 14 January 2019.

- ISSN 1789-0446– via ResearchGate.

- ^ Rothchild D (1994). The Rising Tide of Cultural Pluralism: The Nation-State at Bay?. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 139.

- ^ "Ethiopian Treasures - Emperor Yohannes IV, Battle of Metema - Ethiopia". www.ethiopiantreasures.co.uk.

- ^ ""One Hundred Ways of Putting Pressure"". Human Rights Watch. 24 March 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook" (PDF). IMF. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Ethiopia: IMF Positive on Country's Growth Outlook". allAfrica. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "With Continued Rapid Growth, Ethiopia is Poised to Become a Middle Income Country by 2025". Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Economic Overview". World Bank. 23 September 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ "Ethiopia to launch four more industry parks within two years". Reuters. 9 November 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Sze M (12 August 2019). "Ethiopia to Open Banks for Ethiopian Investors in the Diaspora". W7 News. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Business Corruption in Ethiopia". Business Anti-Corruption Portal. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ "Six million children threatened by Ethiopia drought: UN". Terradaily.com. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ Eastwood V, Elbagir N (31 May 2012). "Ethiopia powers on with controversial dam project". CNN. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Power generation begins at 1,870-MW Gibe III hydroelectric project in Ethiopia". www.hydroworld.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- PMID 30715125.

- ^ "Get the gangsters out of the food chain". The Economist. 7 June 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ^ a b "National Accounts Estimates of Main Aggregates". The United Nations Statistics Division. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Tikuye E (21 January 2023). "Fixing Addis light rail may cost at least $60 million". The Reporter (Ethiopia). Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Mengesha S (15 June 2023). "Ethiopian Airlines flies high with 20% increase in earnings despite global challenges". The Reporter (Ethiopia). Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Ethio Telecom forecasts 19% rise in revenue in 2023/24". Reuters. 28 July 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Ethiopian Coffee Culture – Legend, History and Customs". The Spruce Eats. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ The Economist 22 May 2010, page 49

- ^ "Starbucks in Ethiopia coffee vow". BBC. 21 June 2007. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ Stylianou N. "Coffee under threat". BBC News.

- ^ Cook R (2 September 2015). "World Cattle Inventory: Ranking of countries (FAO) | Cattle Network". www.cattlenetwork.com. Farm Journal. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "Ethiopia's flower trade in full bloom". Mail & Guardian. 19 February 2006. Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

Floriculture has become a flourishing business in Ethiopia in the past five years, with the industry's exports earnings set to grow to $100-million by 2007, a five-fold increase on the $20-million earned in 2005. Ethiopian flower exports could generate an estimated $300-million within two to three years, according to the head of the government export-promotion department, Melaku Legesse.

- ^ a b c d Pavanello, Sara 2010. Working across borders – Harnessing the potential of cross-border activities to improve livelihood security in the Horn of Africa drylands Archived 12 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ Averill V (31 May 2007). "Ethiopia's designs on leather trade". BBC. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

The label inside the luxuriously soft black leather handbag reads Taytu: Made In Ethiopia. But the embroidered print on the outside, the chunky bronze rings attached to the fashionably short straps and the oversized "it" bag status all scream designer chic.

- ^ "Largest hydro electric power plant goes smoothly". English.people.com.cn. 12 April 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ "Hydroelectric Power Plant built". Addistribune.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ "The "white oil" of Ethiopia". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2007.. ethiopianreporter.com

- ^ Independent Online (18 April 2006). "Ethiopia hopes to power neighbors with dams". Int.iol.co.za. Archived from the original on 12 June 2006. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ "Ethiopia–Djibouti electric railway line opens". railwaygazette.com. 5 October 2016. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ "Project Summary". AKH Project owners. January 2017. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "List of all airports in Ethiopia". airport-authority.com. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook – Rank Order – Area". Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ^ "UNESCO World Heritage Centre – World Heritage List". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ "Does It Snow In Ethiopia [Winter Travel]". 15 January 2023.

- ^ "While Egypt Struggles, Ethiopia Builds over the Blue Nile: Controversies and the Way Forward". Brookings.edu.

- S2CID 155380174.

- ^ "Ethiopia, Climate Change and Migration: A little more knowledge and a more nuanced perspective could greatly benefit thinking on policy – Ethiopia". ReliefWeb. 6 December 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Dahir AL (5 March 2019). "Ethiopia is launching a global crowdfunding campaign to give its capital a green facelift". Quartz Africa. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ "Ethiopia PM hosts 'most expensive dinner'". 20 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ AfricaNews (14 May 2019). "Ethiopia PM raises over $25m for project to beautify Addis Ababa". Africanews. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ Addisstandard (25 April 2019). "News: China's reprieve on interest-free loan only". Addis Standard. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ Lepage D. "Bird Checklists of the World". Avibase. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ Bicyclus, Site of Markku Savela

- ^ Bakerova, Katarina et al. (1991) Wildlife Parks Animals Africa. Retrieved 24 May 2008, from the African Cultural Center Archived 5 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Nations. Ethiopia Environment.

- ^ Kurpis, Lauren (2002). How to Help Endangered Species Archived 4 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Endangeredspecie.com

- ^ United Nations Statistics Division, Millennium Development Goals indicators: Carbon dioxide emissions (CO2), thousand tonnes of CO2 (collected by CDIAC) Human-produced, direct emissions of carbon dioxide only. Excludes other greenhouse gases; land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF); and natural background flows of CO2 (See also: Carbon cycle)

- ^ a b Massicot, Paul (2005). Animal Info-Ethiopia.

- PMC 4920324.

- ^ Mongabay.com Ethiopia statistics. (n.d). Retrieved 18 November 2006, from Rainforests.mongabay.com

- PMID 33293507.

- ^ "Ethiopia: Environmental Profile". Mongabay. 4 February 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ISBN 978-93-80228-48-8.

- ^ Parry, J (2003). Tree choppers become tree planters. Appropriate Technology, 30(4), 38–39. Retrieved 22 November 2006, from ABI/INFORM Global database. (Document ID: 538367341).

- CIA. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

landlocked – entire coastline along the Red Sea was lost with the de jure independence of Eritrea on 24 May 1993; Ethiopia is, therefore, the most populous landlocked country in the world

- ^ "Population, total | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Time Europe. 9 August 1926. Archived from the originalon 6 February 2004. Retrieved 5 June 2005.

- ^ "World Refugee Survey 2008". U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. 19 June 2008. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Glottolog 4.8 - Languages of Ethiopia". glottolog.org. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Languages of Ethiopia". Ethnologue. SIL International. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ISBN 978-99944-55-47-8.

- ^ FDRE. "Federal Negarit Gazeta Establishment Proclamation" (PDF). Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-3-86537-839-2.

- ^ Fattovich, Rodolfo (2003) "Akkälä Guzay" in von Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C. Weissbaden: Otto Harrassowitz KG, p.169.

- S2CID 162289324.

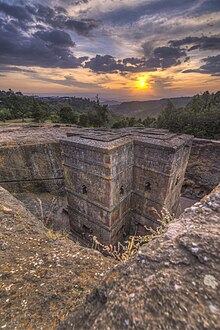

- ^ "Rock-Hewn Churches, Lalibela". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- ^ a b Abegaz B (1 June 2005). "Ethiopia: A Model Nation of Minorities" (PDF). Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^ Pew Forum on Religious & Public life. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2013

- ISBN 978-0-8146-5616-7.

- ^ "The History of Ethiopian Jews". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-4191-1857-9.

- ^ Racin, L. (4 March 2008) "Future Shock: How Environmental Change and Human Impact Are Changing the Global Map". Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

- ^ a b Ofcansky, T and Berry, L. "Ethiopia: A Country Study". Edited by Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991. Countrystudies.us

- ^ a b c d e f Shivley, K. "Addis Ababa, Ethiopia" Macalester.edu Archived 11 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- doi:10.1016/0169-5150(91)90022-D (inactive 31 March 2024).)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of March 2024 (link - ^ a b c d Worldbank.org. Retrieved 5 October 2008 [not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions At Wereda Level from 2014 – 2017". Government of Ethiopia. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Crawley, Mike. "Breaking the Cycle of Poverty in Ethiopia" Archived 25 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. April 2003. International Development Research Centre. Retrieved on 24 May 2008

- ^ "Poverty in Ethiopia Down 33 Percent Since 2000". Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Condominium housing in Ethiopia". Archived from the original on 4 January 2017.

- ^ (Kater, 2000).

- ^ (Dorman et al., 2009, p. 622).

- ^ "Ethiopia MDG Report (2014)". UNDP in Ethiopia. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ "WaterAid UK – Where we work – Ethiopia". www.wateraid.org. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Ethiopia – Health and Welfare". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ "Global distribution of health workers in WHO Member States" (PDF). The World Health Report 2006. World Health Organization. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ^ "National Mental Health Strategy of Ethiopia". Mental Health Innovation Network. 14 August 2014.

- ^ "Ethiopia". Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 9 September 2015.

- PMID 28603550.

- ISBN 978-0-253-34186-0.

- ^ "Education in Ethiopia". WENR. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Ethiopian National Exam Result 2022–2023". NEAEA 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Engel J. "Ethiopia's progress in education: A rapid and equitablension of access – Summary" (PDF). Development Progress. Overseas Development Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ IIEP-UNESCO (2017). "Search Result: Ethiopia's plans and policies". Planipolis.

- ^ UNESCO (2015). National EFA review, 2015 (PDF). UNESCO. p. 8.

- ^ "Literacy" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine in The World Factbook. cia.gov.

- ^ Nations U (January 2015). "National Human Development Report 2015 Ethiopia | Human Development Reports". hdr.undp.org. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ UIS. "Education". data.uis.unesco.org.

- S2CID 46723065.

- ^ "The Use of DMT in Early Masonic Ritual". Reality Sandwich. 27 April 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Aksumite architecture: Architecture of Ethiopia". RTF | Rethinking The Future. 19 February 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Architecture of Aksun and Lalibela". kolibri.teacherinabox.org.au. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Alòs-Moner AM. "Gondarine Art and Architecture (HaAh 523) – Course Syllabus".

- ^ .

- ^ a b c Aga MT. "20 Of The Best Poets And Poems of Ethiopia (Qene included) — allaboutETHIO". allaboutethio.com. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-4472-6.

- ^ Doyle LR. "The Borana Calendar Reinterpreted". tusker.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008.

- ^ "The Simpsons Episode Well-Received by Ethiopians On Social Media". Tadias Magazine. 1 December 2011.

- PMID 26760739.

- ^ "Culture of the people of Tigrai". Tigrai Online. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Jeffrey J (21 December 2017). "Ethiopia's New Addiction – And What It Says About Media Freedom". Inter Press Service News Agency. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ a b Gaffey C (1 June 2017). "Why has Ethiopia pulled its mobile internet access again?". Newsweek. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ "Ethiopia Internet Users". Internet Live Stats. 1 July 2016.

- ^ "What is behind Ethiopia's wave of protests?". BBC News. 22 August 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ "Ethiopia blocks social media sites over exam leak". Al Jazeera. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Sharkov D (12 July 2016). "Ethiopia has shut down social media and here's why". Newsweek. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ "Aklilu Lemma". Right Livelihood. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Zeresenay Alemseged – National Geographic Society". www.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Science And Technology". MICE Ethiopia. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "Timnit Gebru: The 100 Most Influential People of 2022". Time. 23 May 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ "Ethiopian Traditional Medications and their Interactions with Conventional Drugs". EthnoMed. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- . Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-313-31333-2.

Somali music, a unique kind of music that might be mistaken at first for music from nearby countries such as Ethiopia, the Sudan, or even Arabia, can be recognized by its own tunes and styles.

- ISBN 978-0-932415-97-4.

Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan have significant similarities emanating not only from culture, religion, traditions, history and aspirations ... They appreciate similar foods and spices, beverages and sweets, fabrics and tapestry, lyrics and music, and jewellery and fragrances.

- ^ "About St. Yared – St. Yared Ethiopian Cuisine & Coffeehaus – Indianapolis IN". www.styaredcuisine.com. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ Aga MT. "Music in Ethiopia — allaboutETHIO". allaboutethio.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Gumma Film Awards". Addis Standard. 5 July 2022.

- ^ "Addis International Film Festival | Human Rights Film Network". www.humanrightsfilmnetwork.org. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ "Ethiopian International Film Festival". ethiopianfilminitiative.org. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ "Ethiopian Olympic Committee". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ "Athletics – Abebe Bikila (ETH)". International Olympic Committee. 13 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Mehrish A (31 October 2022). "History makers: Ethiopia's role in the creation of CAF, AFCON". FIFA. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

General sources

- Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: The Era of the Princes; The Challenge of Islam and the Re-unification of the Christian Empire (1769–1855). London, England: Longmans.

- Beshah, Girma, Aregay, Merid Wolde (1964). The Question of the Union of the Churches in Luso-Ethiopian Relations (1500–1632). Lisbon: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar and Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos.

- Connel D, Killion T (2011). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. The Scarecrow. ISBN 978-0-8108-5952-4.

- Lyons T (1996). "Closing the Transition: the May 1995 Elections in Ethiopia". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 34 (1): 121–42. S2CID 155079488.

- Munro-Hay, Stuart (1991). Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity (PDF). Edinburgh: University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0106-6. Archived from the original(PDF) on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Pankhurst R (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-0-932415-19-6.

- Valdes Vivo, Raul (1977). Ethiopia's Revolution. New York, NY: International Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7178-0556-3.

Further reading

- Campbell G, Miers S, Miller J (2007). Women and Slavery: Africa, the Indian Ocean world, and the medieval north Atlantic. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1723-2.

- Cana FR, Gleichen AE (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). pp. 82–95.

- Deguefé, Taffara (2006). Minutes of an Ethiopian Century, Shama Books, Addis Ababa, ISBN 99944-0-003-7.

- Hugues Fontaine, Un Train en Afrique. African Train, Centre Français des Études Éthiopiennes / Shama Books. Édition bilingue français / anglais. Traduction : Yves-Marie Stranger. Postface : Jean-Christophe Belliard. Avec des photographies de Matthieu Germain Lambert et Pierre Javelot. Addis Abeba, 2012, ISBN 978-99944-867-1-7. English and French. UN TRAIN EN AFRIQUE

- Henze PB (2004). Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. Shama Books. ISBN 978-1-931253-28-4.

- Keller E (1991). Revolutionary Ethiopia From Empire to People's Republic. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20646-6.

- Marcus HG (1975). The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia, 1844–1913. Oxford: Clarendon. Reprint, Trenton, NJ: Red Sea, 1995. ISBN 1-56902-009-4.

- Marcus HG (2002). A History of Ethiopia (updated ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22479-7.

- Mauri, Arnaldo (2010). Monetary developments and decolonization in Ethiopia, Acta Universitatis Danubius Œconomica, VI, n. 1/2010, pp. 5–16. Monetary Developments and Decolonization in Ethiopia and WP Monetary developments and decolonization in Ethiopia

- Mockler A (1984). Haile Selassie's War. New York: Random House. Reprint, New York: Olive Branch, 2003. ISBN 0-902669-53-2.

- ISBN 0-7126-3044-9

- Rubenson S (2003). The Survival of Ethiopian Independence (4th ed.). Hollywood, CA: Tsehai. ISBN 978-0-9723172-7-6.

- ISBN 978-0-948390-40-1.

- Siegbert Uhlig, et al. (eds.) (2003). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Vol. 1: A–C. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Siegbert Uhlig, et al. (eds.) (2005). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Vol. 2: D–Ha. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Siegbert Uhlig, et al. (eds.) (2007). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Vol. 3: He–N. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Siegbert Uhlig & Alessandro Bausi, et al. (eds.) (2010). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Vol. 4: O–X. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Alessandro Bausi & S. Uhlig, et al. (eds.) (2014). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Vol. 5: Y–Z and addenda, corrigenda, overview tables, maps and general index. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Zewde B (2001). A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855–1991 (2nd ed.). Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1440-8.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

External links

- Ethiopia. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- BBC Ethiopia Profile

- World Bank Ethiopia Summary Trade Statistics

- Ethiopia at Curlie

- Key Development Forecasts for Ethiopia from International Futures.

- Ethiopia pages – U.S. Dept. of State (which includes current State Dept. press releases and reports on Ethiopia)