Ethiopian historiography

Ethiopian historiography includes the

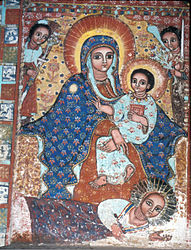

Ethiopian historiographic literature has been traditionally dominated by

During the 16th century and onset of the

Ancient origins

Epigraphy

The roots of the

In

Manuscripts

Aside from epigraphy, Aksumite historiography also includes the

Medieval historiography

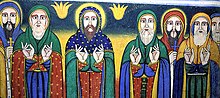

Zagwe dynasty

The power of the Aksumite Kingdom declined after the 6th century due to the rise of other regional states in the

Solomonic dynasty

When the forces of

The most common form of written history sponsored by the Solomonic royal court was the biography of contemporary rulers, who were often lauded by their biographers along with the Solomonic dynasty. The royal biographical genre was established during the reign of

There are also

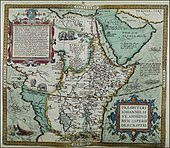

Medieval Europe and the search for Prester John

In

In his 1324 Book of Marvels the

Islamic historiography

Ethiopia is mentioned in some works of

Chinese historiography

Contacts between the Ethiopian Empire and

The Wenxian Tongkao describes the

Early Modern historiography

Conflict and interaction with foreign powers

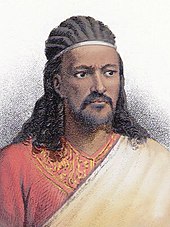

During the 16th century the Ethiopian biographical tradition became far more complex,

The biography of Galawdewos' brother and successor

By the 16th century Ethiopian works began to discuss the profound impact of foreign peoples in their own regional history. The chronicle of Gelawdewos explained the friction between the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the

Biographical chronicles and dynastic histories

At least as far back as the reign of Susenyos I the Ethiopian royal court employed an official court historian known as a

Modern historiography

Era of the Princes

The chaotic period known as the

Another genre of history writing produced during the Era of the Princes was the terse Ethiopian

Biographical literature

Various biographies of Ethiopian emperors have been compiled in the modern era. In 1975 the

Ethiopian and Western historiography

Edward Ullendorff considered the German

Ethiopian historians such as Taddesse Tamrat (1935–2013) and Sergew Hable Sellassie have argued that modern Ethiopian studies were an invention of the 17th century and originated in Europe.[80] Tamrat considered Carlo Conti Rossini's 1928 Storia d'Etiopia a groundbreaking work in Ethiopian studies.[80] The philosopher Messay Kebede likewise acknowledged the genuine contributions of Western scholars to the understanding of Ethiopia's past.[84][85] But he also criticized the perceived scientific and institutional bias that he found to be pervasive in Ethiopian-, African-, and Western-made historiographies on Ethiopia.[86] Specifically, Kebede took umbrage at E. A. Wallis Budge's translation of the Kebra Nagast, arguing that Budge had assigned a South Arabian origin to the Queen of Sheba although the Kebra Nagast itself did not indicate such a provenience for this fabled ruler. According to Kebede, a South Arabian extraction was contradicted by biblical exegetes and testimonies from ancient historians, which instead indicated that the Queen was of African origin.[87] Additionally, he chided Budge and Ullendorff for their postulation that the Aksumite civilization was founded by Semitic immigrants from South Arabia. Kebede argued that there is little physical difference between the Semitic-speaking populations in Ethiopia and neighboring Cushitic-speaking groups to validate the notion that the former groups were essentially descendants of South Arabian settlers, with a separate ancestral origin from other local Afroasiatic-speaking populations. He also observed that these Afroasiatic-speaking populations were heterogeneous, having interbred with each other and also assimilated alien elements of both uncertain extraction and negroid origin.[88]

Synthesis of native and Western historiographic methods

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ethiopian

Takla Sadeq Makuriya (1913–2000), historian and former head of the National Archives and Library of Ethiopia, wrote various works in Amharic as well as foreign languages, including a four-volume Amharic-language series on the history of Ethiopia from ancient times until the reign of Selassie, published in the 1950s.[95] During the 1980s he published a three-volume tome exploring the reigns of 19th-century Ethiopian rulers and the theme of national unity.[95] He also produced two English chapters on the history of the Horn of Africa for UNESCO's General History of Africa and several French-language works on Ethiopia's church history and royal genealogies.[96] Some volumes from his vernacular survey on general Ethiopian history have been edited and circulated as school textbooks in Ethiopian classrooms by the Ministry of Education.[97] Kebede Michael (1916–1998), a playwright, historian, editor, and director of archaeology at the National Library, wrote works of world history, histories of Western civilization, and histories of Ethiopia, which, unlike his previous works, formed the central focus of his 1955 world history written in Amharic.[98]

Italo-Ethiopian Wars

The decisive victory of the Ethiopian Empire over the

Social class, ethnicity, and gender

Modern historians have taken new approaches to analyzing both traditional and modern Ethiopian historiography. For instance,

By relying on the written works of both Christian and Muslim authors, oral traditions, and modern methods of anthropology, archaeology, and linguistics, Mohammed Hassen, Associate Professor of History at Georgia State University,[108] asserts that the largely non-Christian Oromo people have interacted and lived among the Semitic-speaking Christian Amhara people since at least the 14th century, not the 16th century as is commonly accepted in both traditional and recent Ethiopian historiography.[109] His work also stresses Ethiopia's need to properly integrate its Oromo population and the fact that the Cushitic-speaking Oromo, despite their traditional reputation as invaders, were significantly involved in maintaining the cultural, political, and military institutions of the Christian state.[110]

Middle Eastern versus African studies

In his 1992 review of Naguib Mahfouz's The Search (1964), the Ethiopian scholar Mulugeta Gudeta observed that Ethiopian and Egyptian societies bore striking historical resemblances.[111] According to Haggai Erlich, these parallels culminated in the establishment of the Egyptian abun ecclesiastical office, which exemplified Ethiopia's traditional connection to Egypt and the Middle East.[112] In the earlier part of the 20th century, Egyptian nationalists also propounded the idea of forming a Unity of the Nile Valley, a territorial union that would include Ethiopia. This objective gradually ebbed due to political tension over control of the Nile waters.[113] Consequently, after the 1950s, Egyptian scholars adopted a more distant if not apathetic approach to Ethiopian affairs and academic studies.[114] For instance, the Fifth Nile 2002 Conference held in Addis Ababa in 1997 was attended by hundreds of scholars and officials, among whom were 163 Ethiopians and 16 Egyptians.[112] By contrast, there were no Egyptian attendees at the Fourteenth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies later held in Addis Ababa in 2000, similar to all previous ICES conferences since the 1960s.[114]

Erlich argues that, in deference to their training as Africanists, native and foreign Ethiopianists of the post-1950 generation focused more on historiographic matters pertaining to Ethiopia's place within the African continent.[114] This trend had the effect of marginalizing Ethiopia's traditional bonds with the Middle East in historiographic works.[114] In Bahru Zewde's retrospective on Ethiopian historiography published in 2000, he highlighted Ethiopia's ancient tradition of historiography, observing that it dates from at least the fourteenth century and distinguishes the territory from most other areas in Africa.[115] He also noted a shift in emphasis in Ethiopian studies away from the field's traditional fixation on Ethiopia's northern Semitic-speaking groups, with an increasing focus on the territory's other Afroasiatic-speaking communities. Zewde suggested that this development was made possible by a greater critical usage of oral traditions.[116] He offered no survey of Ethiopia's role in Middle Eastern studies and made no mention of Egyptian-Ethiopian historical relations.[117] Zewde also observed that historiographic studies in Africa were centered on methods and schools that were primarily developed in Nigeria and Tanzania, and concluded that "the integration of Ethiopian historiography into the African mainstream, a perennial concern, is still far from being achieved to a satisfactory degree."[117]

See also

- Outline of Ethiopia

- Hatata

- Historiography and nationalism

- Index of Ethiopia-related articles

- List of legendary monarchs of Ethiopia

- Military history of Ethiopia

- Orientalism

- Zera Yacob (philosopher)

- Rosetta stone

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Robin (2012), p. 276.

- ^ a b c Anfray (2000), p. 375.

- ^ a b Robin (2012), p. 273.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 14–15.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), p. 15.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), p. 16.

- ^ Robin (2012), pp. 273–274.

- ^ Robin (2012), pp. 274–275.

- ^ a b Robin (2012), p. 275.

- ^ Robin (2012), pp. 275–276.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 25, 28.

- ^ a b c Anfray (2000), p. 372.

- ^ Robin (2012), p. 277.

- ^ Robin (2012), pp. 277–278.

- ^ Robin (2012), p. 278.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 15–16.

- ^ Anfray (2000), p. 376.

- ^ Riches (2015), pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Sobania (2012), p. 462.

- ^ a b c De Lorenzi (2015), p. 17.

- ^ a b Augustyniak (2012), pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Augustyniak (2012), p. 16.

- ^ Augustyniak (2012), p. 17.

- ^ Riches (2015), p. 44.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Phillipson (2014), pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Phillipson (2014), p. 66.

- ^ a b c De Lorenzi (2015), p. 18.

- ISBN 0631224939.

- ^ Tibebu (1995), p. 13.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), p. 13.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), p. 19.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), pp. 19–21.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), p. 20.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), pp. 16–19.

- ^ a b Baldridge (2012), p. 22.

- ISSN 0041-977X.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), pp. 22–23.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), p. 23.

- ^ a b Milkias (2015), p. 456.

- ^ Smidt (2001), p. 6.

- ^ Braukämper (2004), pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b Braukämper (2004), p. 77.

- ^ Braukämper (2004), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Africanus (1896), pp. 20, 30.

- ^ a b c d e f Abraham, Curtis. (11 March 2015). "China’s long history in Africa Archived 2017-08-02 at the Wayback Machine ". New African. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Friedrich Hirth (2000) [1885]. Jerome S. Arkenberg (ed.). "East Asian History Sourcebook: Chinese Accounts of Rome, Byzantium and the Middle East, c. 91 B.C.E. – 1643 C.E." Fordham University. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Bai (2003), pp. 242–247.

- ^ Smidt (2001), pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f De Lorenzi (2015), p. 20.

- ^ Abir (1980), pp. 211–217.

- ^ Cohen (2009), pp. 106–107.

- ^ Cohen (2009), p. 106.

- ^ Pennec (2012), pp. 83–86, 91–92.

- ^ Cohen (2009), pp. 107–108.

- ^ Pennec (2012), pp. 87–90, 92–93.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c d e f De Lorenzi (2015), p. 22.

- ^ Milkias (2015), p. 474.

- ^ a b c d De Lorenzi (2015), p. 23.

- ^ Bekerie (2013), p. 180.

- ^ Strang (2013), p. 349.

- ^ Rubinkowska (2004), pp. 223–224.

- ^ Rubinkowska (2004), p. 223.

- ^ Omer (1994), p. 97.

- ^ Rubinkowska (2004), p. 223, footnote #9.

- ^ Omer (1994), pp. 97–102.

- ^ College Library, Special Collections. "Hiob Ludolf, Historia Aethiopica (Frankfurt, 1681)". St John's College, Cambridge. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ^ Prichard (1851), p. 139.

- ^ Kebede (2003), p. 1.

- ^ Budge (2014), pp. 183–184.

- ^ Salvadore (2012), pp. 493–494.

- ^ a b Kebede (2003), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Salvadore (2012), p. 493.

- ^ a b c Kebede (2003), p. 2.

- ^ Budge (2014), pp. 184–186.

- ^ Budge (2014), pp. 184–185.

- ^ Budge (2014), p. 186.

- ^ Kebede (2003), pp. 2–4.

- ^ College of Arts and Sciences. "Messay Kebede" University of Dayton. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ Kebede (2003), pp. 2–4 & 7.

- ^ Kebede (2003), p. 4.

- ^ Kebede (2003), pp. 5–7.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 57–59.

- ^ Adejumobi (2007), p. 59.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 58–59.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), p. 58.

- ISBN 978-3-11-019105-9.

- ^ Budge, E. A. Wallis (1928). A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia (Volume I). London: Methuen & Co. p. xv-xvi.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), p. 120.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 120–121.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), p. 121.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 114–116.

- ^ Forclaz (2015), p. 156, note #94.

- ^ Forclaz (2015), p. 156.

- ^ Crummey (2000), p. 319, note #35.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 46, 119–120.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), p. 119.

- ^ Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Illinois.

African Studies Association. (17 November 2014). "Donald Crummey (1941–2013)." Retrieved 24 July 2017. - ^ a b Jalata (1996), p. 101.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 11–12, 121–122.

- ^ Bizuneh (2001), pp. 7–8.

- ^ College of Arts and Sciences (faculty page). "Mohammed Hassen Ali: Associate Professor Archived 2017-08-04 at the Wayback Machine ". Georgia State University. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Hassen (2015), pp. ix–xii.

- ^ Hassen (2015), pp. x–xi.

- ^ Erlich (2002), pp. 215–216, 225 note #18.

- ^ a b Erlich (2002), p. 11.

- ^ Erlich (2002), pp. 5 & 85.

- ^ a b c d Erlich (2002), p. 216.

- ^ Zewde (2000), p. 5.

- ^ Zewde (2000), p. 10.

- ^ a b Erlich (2002), p. 225, note #19.

Sources

- Abir, Mordechai (1980), Ethiopia and the Red Sea: The Rise and Decline of the Solomonic Dynasty and Muslim-European Rivalry in the Region, Abingdon, UK: ISBN 0-7146-3164-7.

- Adejumobi, Saheed A. (2007), The History of Ethiopia, Westport, CT: ISBN 978-0-313-32273-0.

- Africanus, Leo (1896) [1600], Brown, Robert (ed.), The History and Description of Africa, vol. 1, translated by John Pory, London: Hakluyt Society.

- Anfray, F. (2000) [1981], "The Civilisation of Aksum from the First to the Seventh Century", Ancient Civilizations of Africa (reprint ed.), Paris: ISBN 0-435-94805-9.

- Augustyniak, Zuzanna (2012), "Gudit", in Akyeampong, Emmanuel; Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (eds.), Dictionary of African Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 511–512, ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- ISBN 7-101-02890-X.

- Baldridge, Cates (2012), Prisoners of Prester John: The Portuguese Mission to Ethiopia in Search of the Mythical King, 1520-1526, Jefferson, NC: ISBN 978-0-7864-6800-3.

- Bekerie, Ayele (2013), "The 1896 Battle of Adwa and the Forging of the Ethiopian Nation", in Berge, Lars; Taddia, Irma (eds.), Themes in Modern African History and Culture: Festschrift for Tekeste Negash, Padua: Libreria Universitaria, pp. 177–192, ISBN 978-88-6292-363-7.

- Bizuneh, Belete (2001), "Women in Ethiopian History: A Bibliographic Review", Northeast African Studies, 8 (3), Michigan State University Press: 7–32, S2CID 145354978.

- Braukämper, Ulrich (2004), Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: Collected Essays, Münster: ISBN 3-8258-5671-2.

- ISBN 978-1-138-79-155-8.

- Cohen, Leonardo (2009), The Missionary Strategies of the Jesuits in Ethiopia (1555-1632), ISBN 978-3-447-05892-6.

- Crummey, Donald (2000), Land and Society in the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: From the Thirteenth to the Twentieth Century, Urbana, IL: ISBN 0-252-02482-6.

- De Lorenzi, James (2015), Guardians of the Tradition: Historians and Historical Writing in Ethiopia and Eritrea, Rochester: ISBN 978-1-58046-519-9.

- ISBN 1-55587-970-5.

- Forclaz, Amalia Ribi (2015), Humanitarian Imperialism: The Politics of Anti-slavery Activism, 1880–1940, Oxford: ISBN 978-0-19-873303-4.

- Jalata, Asafa (September 1996), "The Struggle for Knowledge: The Case of Emergent Oromo Studies", S2CID 146674050.(subscription required)

- Kebede, Messay (2003), "Eurocentrism and Ethiopian Historiography: Deconstructing Semitization", International Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 1 (1), Tsehai Publishers: 1–19.

- Hassen, Mohammed (2015), The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia, 1300–1700, Woodbridge, UK: ISBN 978-1-84701-117-6.

- Le Grand, M. (1789), Johnson, Samuel (ed.), A voyage to Abyssinia by Father Jerome Lobo a portuguese missionary: containing the history, natural, civil and ecclesiastical of that remote and unfrequented country, translated by Samuel Johnson, London: Elliot and Kay.

- Milkias, Paulos (2015), "Ethiopia", in Falola, Toyin; Jean-Jacques, Daniel (eds.), Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society, Santa Barbara, CA: ISBN 978-1-59884-665-2.

- Munro-Hay, Stuart C. (1981–1982), "A Tyranny of Sources: The History of Aksum from its Coinage", Northeast African Studies, 3 (3): 1–16

- Omer, Ahmed Hassen (December 1994), "Review: Prowess, Piety and Politics: The Chronicles of Abeto Iyasu and Empress Zawditu of Ethiopia (1909–1930). Recorded by Alaqa Gabra Igziabiher Elyas by R. K. Molvaer", Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 27 (2), Institute of Ethiopian Studies: 97–102, JSTOR 41966040.(subscription required)

- Pennec, Herve (2012) [2011], "Missionary Knowledge in Context: Geographical Knowledge of Ethiopia in Dialogue during the 16th and 17th centuries", Written Culture in a Colonial Context: Africa and the Americas 1500–1900 (reprint ed.), Leiden: ISBN 978-90-04-22389-9.

- ISBN 978-99944-52-56-9.

- Prichard, James Cowles (1851), Researches Into the Physical History of Mankind, vol. 2 (4th ed.), London: Houlston and Stoneman.

- Riches, Samantha (2015), St George: A Saint for All, London: ISBN 978-1-78023-4519.

- Robin, Christian Julien (2012), "Arabia and Ethiopia", in Johnson, Scott Fitzgerald (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity, translated by Arietta Papaconstantinou, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 247–334, ISBN 978-0-19-533693-1.

- Rubinkowska, Hanna (2004), "The History That Never Was: Historiography by Haylä Śǝllase I", in Böll, Verena; et al. (eds.), Studia Aethiopica, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 221–233, ISBN 3-447-04891-3.

- Salvadore, Matteo (2012), "Gorgoryos", in Akyeampong, Emmanuel; Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (eds.), Dictionary of African Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 493–494, ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- Smidt, Wolbert (2001), "A Chinese in the Nubian and Abyssinian Kingdoms (8th Century): The visit of Du Huan to Molin-guo and Laobosa" (PDF), Chroniques Yéménites, 9.

- Sobania, Neal W. (2012), "Lalibela", in Akyeampong, Emmanuel; Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (eds.), Dictionary of African Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 462, ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- Strang, G. Bruce (2013), "Select Biography", in Strang, G. Bruce (ed.), Collision of Empires: Italy's Invasion of Ethiopia and its International Impact, Abingdon, UK: ISBN 978-1-4094-3009-4.

- Tibebu, Teshale (1995), The Making of Modern Ethiopia, 1896-1974, Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press, ISBN 1-56902-001-9.

- Yule, Henry (1915), Henry Cordier (ed.), Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route, vol. 1, London: Hakluyt Society.

- Zewde, Bahru (November 2000), "A Century of Ethiopian Historiography", Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 33 (2, Special Issue Dedicated to the XIVth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies), Institute of Ethiopian Studies: 1–26.

Further reading

- Hrbek, Ivan (1981). "Written sources from the fifteenth century onwards". In Ki-Zerbo, Jacqueline (ed.). Methodology and African Prehistory. ISBN 0435948075.

External links

- Bekerie, Ayele (March 8, 2010). "Assumptions and Interpretations of Ethiopian History". Tadias Magazine.

- Dr. Richard Pankhurst, doyen of Ethiopian historians and scholars, has died (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Foreign Affairs)