European Union law

European Union law is a system of rules operating within the

The EU's legal foundations are the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, currently unanimously agreed on by the governments of 27 member states. New members may join if they agree to follow the rules of the union, and existing states may leave according to their "own constitutional requirements".[7] Citizens are entitled to participate through the Parliament, and their respective state governments through the Council in shaping the legislation the EU makes. The Commission has the right to propose new laws (the right of initiative), the Council of the European Union represents the elected member-state governments, the Parliament is elected by European citizens, and the Court of Justice is meant to uphold the rule of law and human rights.[8] As the Court of Justice has said, the EU is "not merely an economic union" but is intended to "ensure social progress and seek the constant improvement of the living and working conditions of their peoples".[9]

History

Democratic ideals of integration for international and European nations are as old as the modern

The French diplomat,

To "save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice.. brought untold sorrow to mankind",

In the West, the decision was made through the

Aside from the European Economic Community itself, the European continent underwent a profound transition towards democracy. The dictators of Greece and Portugal were deposed in 1974, and Spain's dictator died in 1975, enabling their accession in 1981 and 1986. In 1979, the European Parliament had its first direct elections, reflecting a growing consensus that the EEC should be less a union of member states, and more a union of peoples. The 1986 Single European Act increased the number of treaty issues in which qualified majority voting (rather than consensus) would be used to legislate, as a way to accelerate trade integration. The Schengen Agreement of 1985 (not initially signed by Italy, the UK, Ireland, Denmark or Greece) allowed movement of people without any border checks. Meanwhile, in 1987, the Soviet Union's Mikhail Gorbachev announced policies of "transparency" and "restructuring" (glasnost and perestroika). This revealed the depths of corruption and waste. In April 1989, the People's Republic of Poland legalised the Solidarity organisation, which captured 99% of available parliamentary seats in June elections. These elections, in which anti-communist candidates won a striking victory, inaugurated a series of peaceful anti-communist revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe that eventually culminated in the fall of communism. In November 1989, protestors in Berlin began taking down the Berlin Wall, which became a symbol of the collapse of the Iron Curtain, with most of Eastern Europe declaring independence and moving to hold democratic elections by 1991.

The

During the

Constitutional law

Although the European Union does not have a codified constitution,[28] like every political body it has laws which "constitute" its basic governance structure.[29] The EU's primary constitutional sources are the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which have been agreed or adhered to among the governments of all 27 member states. The Treaties establish the EU's institutions, list their powers and responsibilities, and explain the areas in which the EU can legislate with Directives or Regulations. The European Commission has the right to propose new laws, formally called the right of legislative initiative.[30] During the ordinary legislative procedure, the Council (which are ministers from member state governments) and the European Parliament (elected by citizens) can make amendments and must give their consent for laws to pass.[31]

The Commission oversees departments and various agencies that execute or enforce EU law. The "European Council" (rather than the Council of the European Union, made up of different government Ministers) is composed of the Prime Ministers or executive presidents of the member states. It appoints the Commissioners and the board of the European Central Bank. The European Court of Justice is the supreme judicial body which interprets EU law, and develops it through precedent. The Court can review the legality of the EU institutions' actions, in compliance with the Treaties. It can also decide upon claims for breach of EU laws from member states and citizens.

Treaties

- European Union member states (special territories not shown)

- 20 in the eurozone1 in ERM II, with an opt-out (Denmark)5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting the convergence criteria (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden)

- Non–EU member states

The Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) are the two main sources of EU law. Representing agreements between all member states, the TEU focuses more on principles of democracy, human rights, and summarises the institutions, while the TFEU expands on all principles and fields of policy in which the EU can legislate. In principle, the EU treaties are like any other international agreement, which will usually be interpreted according to principles codified by the Vienna Convention 1969.[32] It can be amended by unanimous agreement at any time, but TEU itself, in article 48, sets out an amendment procedure through proposals via the Council and a Convention of national Parliament representatives.[33] Under TEU article 5(2), the "principle of conferral" says the EU can do nothing except the things which it has express authority to do. The limits of its competence are governed by the Court of Justice, and the courts and Parliaments of member states.[34]

As the European Union has grown from 6 to 27 member states, a clear procedure for accession of members is set out in TEU article 49. The European Union is only open to a "European" state which respects the principles of "human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law, and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities". Countries whose territory is wholly outside the European continent cannot therefore apply.[35] Nor can any country without fully democratic political institutions which ensure standards of "pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail".[36] Article 50 says any member state can withdraw in accord "with its own constitutional requirements", by negotiated "arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union". This indicates that the EU is not entitled to demand a withdrawal, and that member states should follow constitutional procedures, for example, through Parliament or a codified constitutional document.[7] Once article 50 is triggered, there is a two-year time limit to complete negotiations, a procedure which would leave a seceding member without any bargaining power in negotiations, because the costs of having no trade treaty would be proportionally greater to the individual state than the remaining EU bloc.[37]

Article 7 allows member states to be suspended for a "clear risk of a serious breach" of values in article 2 (for example, democracy, equality, human rights) with a four-fifths vote of the

Executive institutions

The European Commission is the main executive body of the European Union.[40] Article 17(1) of the Treaty on European Union states the commission should "promote the general interest of the Union" while Article 17(3) adds that Commissioners should be "completely independent" and not "take instructions from any Government". Under Article 17(2), "Union legislative acts may only be adopted on the basis of a Commission proposal, except where the Treaties provide otherwise". This means that the commission has a monopoly on initiating the legislative procedure, although the council or Parliament are the "de facto catalysts of many legislative initiatives".[41]

The commission's President (as of 2021[update] Ursula von der Leyen) sets the agenda for its work.[43] Decisions are taken by a simple majority vote,[44] often through a "written procedure" of circulating the proposal and adopting it if there are no objections.[citation needed] In response to Ireland's initial rejection of the Treaty of Lisbon, it was agreed to keep the system of one Commissioner from each of the member states, including the President and the High Representative for Foreign and Security Policy (currently Josep Borrell)[45] The Commissioner President is elected by the European Parliament by an absolute majority of its members, following the parliamentary elections every five years, on the basis of a proposal by the European Council. The latter must take account of the results of the European elections, in which European political parties announce the name of their candidate for this post. Hence, in 2014, Juncker, the candidate of the European People's Party which won the most seats in Parliament, was proposed and elected.

The remaining commissioners are appointed by agreement between the president-elect and each national government, and are then, as a block, subject to a

Beyond the commission, the European Central Bank has relative executive autonomy in its conduct of monetary policy for the purpose of managing the euro.[51] It has a six-person board appointed by the European Council, on the Council's recommendation. The president of the council and a commissioner can sit in on ECB meetings, but do not have voting rights.

Legislature

While the Commission has a monopoly on initiating legislation, the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union have powers of amendment and veto during the legislative process.[53] According to the Treaty on European Union articles 9 and 10, the EU observes "the principle of equality of its citizens" and is meant to be founded on "representative democracy". In practice, equality and democracy are still in development because the elected representatives in the Parliament cannot initiate legislation against the commission's wishes,[54] citizens of smallest countries have greater voting weight in Parliament than citizens of the largest countries,[55] and "qualified majorities" or consensus of the council are required to legislate.[56] This "democratic deficit" has encouraged numerous proposals for reform, and is usually perceived as a hangover from earlier days of integration led by member states. Over time, the Parliament gradually assumed more voice: from being an unelected assembly, to its first direct elections in 1979, to having increasingly more rights in the legislative process.[57] Citizens' rights are therefore limited compared to the democratic polities within all European member states: under TEU article 11, citizens and associations have the right to publicise their views and the right to submit an initiative that must be considered by the Commission if it has received at least one million signatures. TFEU article 227 contains a further right for citizens to petition the Parliament on issues which affect them.[58]

The second main legislative body is the Council of the European Union, which is composed of different ministers of the member states. The heads of government of member states also convene a "

To make new legislation, TFEU article 294 defines the "

Judiciary

The judiciary of the EU has played an important role in the development of EU law. It interprets the

The

Conflict of laws

Since its founding, the EU has operated among an increasing

Generally speaking, while all member states recognise that EU law takes primacy over national law where this agreed in the Treaties, they do not accept that the Court of Justice has the final say on foundational constitutional questions affecting democracy and human rights. In the United Kingdom, the basic principle is that Parliament, as the sovereign expression of democratic legitimacy, can decide whether it wishes to expressly legislate against EU law.

As opposed to the member states, the relation of EU law and international law is debated, particularly relating to the

Administrative law

While constitutional law concerns the

Direct effect

Although it is generally accepted that EU law has primacy, not all EU laws give citizens standing to bring claims: that is, not all EU laws have "

While the Treaties and Regulations will have direct effect (if clear, unconditional and immediate),

First, if a Directive's deadline for implementation is not met, the member state cannot enforce conflicting laws, and a citizen may rely on the Directive in such an action (so called "vertical" direct effect). So, in

Fifth, national courts have a duty to interpret domestic law "as far as possible in the light of the wording and purpose of the directive".

References and remedies

Litigation often begins and is resolved by member state courts. They interpret and apply EU law, and award remedies of

On the other side, courts and tribunals are theoretically under a duty to refer questions. In the UK, for example,

If references are made, the Court of Justice will give a preliminary ruling, in order for the member state court to conclude the case and award a remedy. The

Judicial review

As well as preliminary rulings on the proper interpretation of EU law, an essential function of the

However, only a limited number of people can bring claims for judicial review. Under TFEU article 263(2), a member state, the Parliament, Council or Commission have automatic rights to seek judicial review. But under article 263(4) a "natural or legal person" must have a "direct and individual concern" about the regulatory act. "Direct" concern means that someone is affected by an EU act without "the interposition of an autonomous will between the decision and its effect", for instance by a national government body.

Human rights and principles

Although access to judicial review is restricted for ordinary questions of law, the Court of Justice has gradually developed a more open approach to standing for human rights. Human rights have also become essential in the proper interpretation and construction of all EU law. If there are two or more plausible interpretations of a rule, the one which is most consistent with human rights should be chosen. The

Many of the most important rights were codified in the

Beyond human rights, the Court of Justice has recognised at least five further 'general principles' of EU law. The categories of general principles are not closed, and may develop according to the social expectations of people living in Europe.

- Legal certainty requires that judgments should be prospective, open and clear.

- Decision-making must be "proportionate" toward a legitimate aim when reviewing any discretionary act of a government or powerful body, for example, if a government wishes to change an employment law in a neutral way, yet this could have disproportionate negative impact on women rather than men, the government must show a legitimate aim, and that its measures are (1) appropriate or suitable for achieving it, (2) do no more than necessary, and (3) reasonable in balancing the conflicting rights of different parties.[173]

- Equality is regarded as a fundamental principle: this matters particularly for labour rights, political rights, and access to public or private services.[174]

- Right to a fair hearing.

- Professional privilege between lawyers and clients.

Free movement and trade

While the "

Goods

Free movement of goods within the

Generally speaking, if a member state has laws or practices that directly discriminate against imports (or exports under TFEU article 35) then it must be justified under article 36. The justifications include public

Often rules apply to all goods neutrally, but may have a greater practical effect on imports than domestic products. For such "indirect" discriminatory (or "indistinctly applicable") measures the Court of Justice has developed more justifications: either those in article 36, or additional "mandatory" or "overriding" requirements such as

In a 2003 case,

In contrast to product requirements or other laws that hinder

Workers

Since its foundation, the Treaties sought to enable people to pursue their life goals in any country through free movement.

The

Citizens

Beyond the right of free movement to work, the EU has increasingly sought to guarantee rights of citizens, and rights simply be being a

First, the

Fourth, and more debated, article 24 requires that the longer an EU citizen stays in a host state, the more rights they have to access public and welfare services, on the basis of

Establishment and services

As well as creating rights for "workers" who generally

In regard to companies, the Court of Justice held in

The "freedom to provide services" under TFEU article 56 applies to people who give services "for remuneration", especially commercial or professional activity.

If an activity does fall within article 56, a restriction can be justified under article 52, or by overriding requirements developed by the Court of Justice. In

Capital

Free movement of

The final stage of completely free movement of capital was thought to require a

Social and market regulations

While the

EU law makes basic standards of "exit" (where markets operate), rights (enforceable in court), and "voice" (especially through

Consumer protection

Protection of European consumers has been a central part of developing the EU internal market. The

The

The

- Unfair Commercial Practices Directive 2005/29/EC

- Consumer Rights Directive 2011/83/EU

- Payment Services Directive 2007/64/EC

- Late Payments Directive2011/7/EU

Labour rights

While

The first group of Directives create a range of individual rights in EU employment relationships. The

Third, the EU is formally not enabled to legislate on

Companies and investment

Like labour regulation,

Among the most important governance standards are rights

Competition law

Competition law aims "to prevent competition from being distorted to the detriment of the public interest, individual undertakings and consumers", especially by limiting big business power.

First,

Under the third type of abuse, (c) unlawful discrimination, in

Third,

Commerce and intellectual property

While EU law has not yet developed a civil code for contracts, torts, unjust enrichment, real or personal property, or commerce in general,

Unlike other property forms, intellectual property rights are comprehensively regulated by a series of directives on copyrights, patents and trademarks. The

Public regulation

A major part of EU law, and most of the EU's budget, concerns public regulation of enterprise and public services. A basic norm of the

Education and health

Education and health are provided mainly by member states, but shaped by common minimum standards in EU law. In the case of education, the

As in education, there is a universal human right to 'health and well-being' including 'medical care and necessary social services',

Banking, monetary and fiscal policy

Banking, monetary and fiscal policy is overseen by the

The European Central Bank's 'primary objective... shall be to maintain

Beyond the central bank, the

The

Electricity and energy

Like the world, the EU's greatest task is to replace fossil fuels with clean energy as fast as technology allows since protection of "life",

A growing number of cases seek to enforce liability on gas, oil and coal polluters.

As clean energy from

The third main set of standards is that the EU requires that electricity or gas enterprises acquire a licence from member state authorities.[458] There must be legal separation into different entities of owners of networks from retailers, although they can be owned by the same enterprise, to ensure transparency of accounting.[459] Then, different enterprises have rights to access infrastructure of network owners on fair and transparent terms,[460] as a way to ensure different member state networks and supplies can become integrated across the EU. Most EU operators are publicly owned, and the Court of Justice in Netherlands v Essent NV emphatically rejected that there was any violation of EU law on free movement of capital by a Dutch Act requiring electricity and gas distributors to be publicly owned, that system operators could not be connected by ownership to generators, and limited the level of debt.[461] The Court of Justice held a public ownership requirement was justified by 'overriding reasons in the public interest', 'to protect consumers' and for the 'security of energy supply'.

Agriculture, forestry and water

Everyone has the right to food and water,

The CAP has three main parts. First, the

Outside farms, forests cover just 43.52% of the EU's land, compared to 80% forest cover

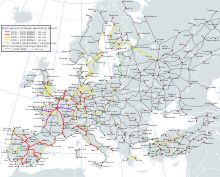

Transport and buildings

Clean road, rail, sea and air transport are fundamental goals of the EU, given its commitment to human rights for 'improvement of the quality of the environment', 'services of general economic interest',

In road transport, the

People need to have a driving licence to drive on a road, and there is a common system of recognition around the EU.[507] For delivery vehicle workers, the Road Transport Regulation 2006 limits daily driving time to 9 hours a day, a maximum of 56 hours a week, and requires at least a 45-minute break after 4+1⁄2 hours. Drivers may also not be paid according to distance travelled if this would endanger road safety.[508] Taxi enterprises are usually regulated separately in each member state, and the attempts of the app-based firm Uber to evade regulation by arguing it was not a "transport service" rather than an "Information Society Service" failed.[509] Most bus networks are publicly owned or procured, but there are common rights. If buses are delayed in journeys over 250 kilometres, the Bus Passenger Rights Regulation 2011 entitles passengers to compensation.[510] Under article 19, a delay over two hours must result in compensation of 50% of the ticket price, as well as rerouting and reimbursement. Article 6 says 'Carriers may offer contract conditions that are more favourable for the passenger', although it is not clear many take up this option. Article 7 says member states cannot set maximum compensation for death or injury lower than €220,000 per passenger or €1200 per item of luggage. There is not yet a requirement for the major bus, delivery, taxi enterprises to electrify their fleets even though this would create the fastest reduction of emissions and would be cheaper for business in total operating costs.[511]

In rail transport, the

Finally, the 'right to housing assistance' is a basic part of EU law.[515] House prices are affected by monetary policy (above), but otherwise the EU's involvement is so far limited to minimal environmental standards. The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive 2010 aims to eliminate unclean materials and energy waste to have "nearly zero-energy buildings", particularly by setting standards for new buildings since 2020 and upgrading existing buildings by 2050.[516] There is, however, no requirement yet that all buildings replace gas heating with electric or heat-pumps, have solar or wind energy generation, electric vehicle charging, and particular insulation standards, wherever possible.

Communications and data

The right 'to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers'

Since today's communications have mostly merged into the internet, the Electronic Communications Code Directive 2018 is critical for EU infrastructure.[523] Article 5 requires a member state regulator or a "competent authority" is set up that will license use of the radio spectrum, through which mobile and internet signals travel. A regulator must also enable access and interconnection to other infrastructure (such as telecomms and broadband cables), protect end-user rights, and monitor "competition issues regarding open internet access" to ensure rights such as universal service and portability of phone numbers.[524] Articles 6-8 require the regulators are independent, with dismissal of heads only for a good reason, and articles 10-11 require cooperation with other authorities. Articles 12-13 require that use of electronic communication networks is authorised by a regulator, and that conditions attached are non-discriminatory, proportionate and transparent.[525] The owner of a communication network has duties to allow access and interconnection on fair terms, and so article 17 requires that its accounts and financial reports are separate from other activities (if the enterprise does other business),[526] article 74 foresees that regulators can control prices, and article 84 says member states should "ensure that all consumers in their territories have access at an affordable price, in light of specific national conditions, to an available adequate broadband internet access service and to voice communications services". While some EU member states have privatised all, and some part, of their telecomms infrastructure, publicly or community-owned internet providers (such as in Denmark or Romania) tend to have the fastest web speeds.[527]

Historically to protect people's privacy and correspondence, the post banned tampering with letters, and excluded post offices from responsibility for letters even if the contents were for something illegal.[529] As the internet developed, the original Information Society Directive 1998 aimed for something similar, so that internet server providers or email hosts, for instance, protected privacy.[530] After this the Electronic Commerce Directive 2000 also sought to ensure free movement for an "information society service",[531] requiring member states to not restrict them unless it was to fulfill a public policy, prevent crime, fight incitement to hatred, protect individual dignity, protect health, or protect consumers or investors.[532] Articles 12 to 14 further said that an ISS operating as a "mere conduit" for information, doing "caching" or "hosting" is 'not liable for information stored' if the 'provider does not have actual knowledge of illegal activity' and 'is not aware of facts or circumstances from which the illegal activity or information is apparent', but must act quickly to remove or disable access 'upon obtaining knowledge or awareness'.[533] Article 15 states that member states should 'not impose a general obligation on providers... to monitor the information which they transmit or store' nor 'seek facts' on illegality.[534] However the meaning of who was an "ISS" was not clearly defined in law,[535] and has become a problem with social media that was not meant to be protected like private communication. An internet service provider has been held to be an ISS,[536] and so has a Wi-Fi host,[537] the Electronic Commerce Directive 2000 recital 11 states email services, search engines, data storage, and streaming, are information society services, and an individual email is not,[538] and the Information Society Directive 2015 makes clear that TV and radio stations do not count as ISS's.[539] None of these definitions include advertising, which is never "at the request of a recipient of services" as the 2015 Directive requires, however various cases have decided that eBay,[540] Facebook,[541] and AirBnB,[542] may count as ISSs, but the cab app Uber does not.[543]

The main rights to data privacy are found in the

Media and markets

Pluralism and regulation of the media, such as through 'the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises',[553] have long been seen as essential to protect freedom of opinion and expression,[554] to ensure that citizens have a more equal voice,[555] and ultimately to support the universal 'right to take part in the government'.[556] In almost all member states there is a well funded public, and independent broadcaster for TV and radio, and there are common standards for all TV and radio, which are designed to support open, fact-based discussion and deliberative democracy. However, the same standards have not yet been applied to equivalent internet television, radio or "social media" such as the platforms controlled by YouTube (owned by Alphabet), Facebook or Instagram (owned by Meta), or Twitter (owned by Elon Musk), all of which have spread conspiracy theories, discrimination, far-right, extremist, terrorist, and hostile military content.

General standards for broadcasting are found in the

The EU has also begun to regulate marketplaces that operate online, both through

Foreign, security and trade policy

- Common Foreign and Security Policy, including the Common Security and Defence Policy (funded by the European Defence Fund and European Defence Agency), membership of NATO, the United Nations

- TFEU art 214, Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations

- European Neighbourhood Policy

- European Union free trade agreements, World Trade Organization

- TFEUart 218, advisory opinion procedure on international agreements

Security and justice

- Area of freedom, security and justice and European Arrest Warrant, TFEU art 67

In 2006, a

See also

- EudraLex – EU laws on medicinal products

- Europäische Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsrecht (European Journal of Business Law)

- European Case Law Identifier – Identifier of court judgements in Europe

- European Legislation Identifier – Uniquely identifies national and EU laws

- Incidental effect – European Union law concept

- Precautionary principle – Risk management strategy

- Unitary patent – Potential EU patent law

- List of European Court of Justice rulings

- List of European Union directives

Notes

- ^ "Population on 1 January". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Treaty on European Union art 2

- ^ "Living in the EU". European Union. 5 July 2016.

- ^ See TEU art 3(1) 'The Union's aim is to promote peace, its values and the well-being of its peoples.' (3) '... and shall promote social justice and protection...'

- ^ See TEU arts 3(3) 'It shall work for the sustainable development of Europe based on balanced economic growth and price stability, a highly competitive social market economy, aiming at full employment and social progress, and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment'. Art 4(3) 'Pursuant to the principle of sincere cooperation, the Union and the Member States shall, in full mutual respect, assist each other in carrying out tasks which flow from the Treaties'.

- ^ a b Van Gend en Loos v Nederlandse Administratie der Belastingen (1963) Case 26/62

- ^ a b TEU art 50. On the most sophisticated discussion of constitutional law and human rights principles for secession, see Reference Re Secession of Quebec [1998] 2 SCR 217, particularly [67] "The consent of the governed is a value that is basic to our understanding of a free and democratic society. Yet democracy in any real sense of the word cannot exist without the rule of law". And [149] "Democracy, however, means more than simple majority rule".

- ^ See TEU arts 13–19

- ^ a b Defrenne v Sabena (1976) Case 43/75, [10]

- Henri Saint-Simon.

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2011.

- ^ Craig, P (2014). "2. The Development of the EU". In Barnard, Catherine; Peers, S (eds.). European Union Law.

- ^ W Penn, An ESSAY towards the Present and Future Peace of Europe by the Establishment of an European Dyet, Parliament, or Estates (1693) in AR Murphy, The Political Writings of William Penn (2002) See D Urwin, The Community of Europe: A History of European Integration (1995)

- ^ C de Saint-Pierre, A Project for Settling an Everlasting Peace in Europe (1713)

- (1756)

- I Kant, Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch or Zum ewigen Frieden. Ein philosophischer Entwurf (1795)

- V Hugo, Opening Address to the Peace Congress (21 August 1849). Afterwards, Giuseppe Garibaldi and John Stuart Mill joined Victor Hugoat the Congress of the League of Peace and Freedom in Geneva 1867.

- JM Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace(1919)

- UN Charter 1945 Preamble

- R Schuman, Speech to the French National Assembly (9 May 1950)

- N Khrushchev, On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences(25 February 1956)

- ^ See Comite Intergouvernemental créé par la conference de Messine. Rapport des chefs de delegation aux ministres des affaires etrangeres (21 April 1956 Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine) text in French.

- ^ See the European Communities Act 1972

- ^ See the European Union Referendum Act 2015 (c 36) on the campaign rules for the poll.

- TFEUarts 293–294

- ^ e.g. J Weiler, The Constitution of Europe (1999), C Hoskyns and M Newman, Democratizing the European Union (2000), A Moravcsik, 'In Defence of the "Democratic Deficit": Reassessing Legitimacy in the European Union' (2002) 40 JCMS 603, Craig & de Búrca 2011, ch 2.

- HLA Hart, The Concept of Law(1961) ch 4, on the danger of a static system and "rules of change".

- Netherlands.

- KD Ewing, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2012) ch 1 and W Bagehot, The English Constitution(1867)

- ^ TEU art 17

- ^ TFEU art 294

- ^ Vienna Convention 1969 art 5, on application to constituent instruments of international organisations.

- ^ TEU art 48. This is the "ordinary" procedure, and a further "simplified" procedure for amending internal EU policy, but not increasing policy competence, can work through unanimous member state approval without a Convention.

- ^ See further T Arnull, 'Does the Court of Justice Have Inherent Jurisdiction?' (1990) 27 CMLRev 683

- Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon.

- ^ TEU art 2

- ^ cf S Lechner and R Ohr, 'The right of withdrawal in the treaty of Lisbon: a game theoretic reflection on different decision processes in the EU' (2011) 32 European Journal of Law and Economics 357

- ^ TEU art 7

- TFEU art 273, for a 'special agreement' of the parties, and Pringle v Ireland(2012) C-370/12 held the 'special agreement' could be given in advance with reference to a whole class of pre-defined disputes.

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2015, ch 2, 31–40.

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2015, p. 36.

- TFEU art 282–287

- ^ TEU art 17(6)

- TFEUart 250

- ^ , despite TEU art 17(5) allowing this figure to be reduced to two-thirds of the number of member states. It is now unclear whether this will happen.

- ^ TEU art 17(7)

- ^ Humblet v Belgium (1960) Case 6/60

- ^ Sayag v Leduc (1968) Case 5/68, [1968] ECR 395 and Weddel & Co BV v Commission (1992) C-54/90, [1992] ECR I-871, on immunity waivers.

- ^ (2006) C-432/04, [2006] ECR I-6387

- ^ Committee of Independent Experts, First Report on Allegations of Fraud, Mismanagement and Nepotism in the European Commission (15 March 1999)

- TFEUart 282–287

- ^ c.f. TEU art 9

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2015, chs 2 and 5, 40–56 and 124–160.

- TFEUart 225(2) and 294(2)

- ^ TEU art 14(2) and Council Decision 2002/772

- TFEUart 238(3)

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2015, ch 2(6) 50–51. See also the European Parliament Resolution of 30 March 1962. Recognised in SEA art 3(1). TEEC art 190(4) required proposals for elections

- ^ See Marias, 'The Right to Petition the European Parliament after Maastricht' (1994) 19 ELR 169

- ^ TEU art 14(3) and Decision 2002/772. Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) art 223(1) requires the Parliament to eventually propose a uniform voting system, adopted by the Council, but it is unclear when this may happen.

- ^ TEU art 14(2) reduced from 765 in 2013.

- ^ Germany 96. France 74. UK and Italy 73. Spain 54. Poland 51. Romania 31. Netherlands 26. Belgium, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Portugal 21. Sweden 20. Austria 18. Bulgaria 17. Denmark, Slovakia, Finland 13. Ireland, Croatia, Lithuania 11. Latvia, Slovenia 8. Estonia, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta 6.

- ^ (1986) Case 294/83, [1986] ECR 1339. The Greens challenged funding, contending its distribution was unfair against smaller parties, and it was held all funding was ultra vires. See Joliet and Keeling, 'The Reimbursement of Election Expenses: A Forgotten Dispute' (1994) 19 ELR 243

- TFEUart 226 and 228

- TFEUart 230 and 234

- Roquette v Council (1980) Case 138/79, [1980] ECR 3333 and European Parliament v Council(1995) C-65/93, [1995] ECR I-643, Parliament held not to have done everything it could have done within a sufficient time to give an opinion, so it could not complain the Council had gone ahead. See Boyron, 'The Consultation Procedure: Has the Court of Justice Turned against the European Parliament?' (1996) 21 ELR 145

- ^ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War (ca 411 BC) Book 2, para 37, where Pericles said, 'Our government does not copy our neighbors, but is an example to them. It is true that we are called a democracy, for the administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few'.

- ^ TEU art 15(3) and (6)

- ^ TEU art 15(1)

- ^ TEU art 16(2)

- ^ The numbers are currently Germany, France, Italy, and UK: 29 votes each. Spain and Poland: 27. Romania: 14. Netherlands: 13. Belgium, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Portugal: 12. Bulgaria, Austria, Sweden: 10. Denmark, Ireland, Croatia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Finland: 7. Estonia, Cyprus, Latvia, Luxembourg, Slovenia: 4. Malta: 3. This was set by the 2014 Protocol No 36 on Transitional Provisions, art 3(3) amended by art 20 for Croatia Accession Treaty 2011.

- ^ TFEU art 288 outlines the main legislative acts as Directives, Regulations, and Decisions. Commission v Council (1971) Case 22/70, [1971] ECR 263 acknowledged that the list was not exhaustive, relating to a Council 'resolution' on the European Road Transport Agreement. Atypical acts include communications and recommendations, and white and green papers.

- ^ e.g. M Banks, 'Sarkozy slated over Strasbourg seat' (24 May 2007) EU Politix Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ This does not extend to foreign and security policy, where there must be consensus.

- TFEUart 294

- ^ TFEU art 313–319

- ^ TEU art 20 and TFEU arts 326 and 334

- ^ Protocol No 1 to the Treaty of Lisbon

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2015, ch 2, 57–67.

- TFEU arts 253–254

- ISBN 9783658175696.

- ^ (1963) Case 26/62

- ^ (2005) C-144/04

- ^ (2008) C-402

- TFEUart 253

- TFEUarts 254–255

- Statute of the Court art 20 and Craig & de Búrca 2015, p. 61

- TFEUart 267

- TFEU arts 258–259

- TFEUarts 256, 263, 265, 268, 270, 272

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2015, chs 9–10.

- Ente nazionale per l'energia elettricawas privatised once again in 1999.

- TFEU.

- TEECart 177

- ^ Van Gend en Loos v Nederlandse Administratie der Belastingen (1963) Case 26/62

- ^ a b "EUR-Lex - 61964CJ0006 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ (1964) Case 6/64, [1964] ECR 585

- ^ (1978) Case 106/77, [1978] ECR 629, [17]-[18]

- Lord Denning MR

- ^ [1990] UKHL 7, (1990) C-213/89

- ^ a b [2014] UKSC 3

- Grundgesetz arts 20 and 79(3). Note that "rule of law" may not be a perfect translation of the German concept of "Rechtsstaat".

- Internationale Handelsgesellschaft mbH v Einfuhr- und Vorratsstelle für Getreide und Futtermittel(1970) Case 11/70

- Re Wünsche Handelsgesellschaft(22 October 1986) BVerfGE, [1987] 3 CMLR 225

- Kadi v Commission (2008) C-402 and 415/05

- ^ (2014). In summary, these were it (1) undermined the CJEU's autonomy (2) allowed for a parallel dispute resolution mechanism among member states, when the treaties said the CJEU should be the sole arbiter (3) the "co-respondent" system, allowing the EU and member states to be sued together, allowed the ECtHR to illegitimately interpret EU law and allocate responsibility between the EU and member states, (4) did not allow the Court of Justice to decide if an issue of law was already dealt with, before the ECHR heard a case, and (5) the ECtHR was illegitimately being given power of judicial review over Common Foreign and Security Policy.

- ^ cf P Eeckhout, 'Opinion 2/13 on EU Accession to the ECHR and Judicial Dialogue: Autonomy or Autarky' (2015) 38 Fordham International Law Journal 955 and A Lasowski and RA Wessel, 'When Caveats Turn into Locks: Opinion 2/13 on Accession of the European Union to the ECHR' (2015) 16 German Law Journal 179

- CFREU art 47

- Kadi and Al Barakaat International Foundation v Council and Commission (2008) C-402 and 415/05, [2008] ECR I-6351

- ^ TEU art 6(2) and Opinion 2/13 (2014)

- ^ Marshall v Southampton Health Authority (1986) Case 152/84

- art 47], right to an effective remedy.

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2015, ch 7.

- ^ (1963) Case 26/62

- TEECart 12

- ^ (1972) Case 39/72, [1973] ECR 101

- ^ e.g. Commission v United Kingdom (1979) Case 128/78, Court of Justice held the UK had failed to implement art 21 of the Tachograph Regulation 1463/70, art 4 (now repealed) on time. This said in commercial vehicles use of tachographs (recording devices) was compulsory from a certain date. Art 21(1) then said MSs should, after consulting with the Comm, adopt implementing regulations, and penalties for breach. Potentially it could also not have imposed a criminal offence, as it was far too vague.

- Faccini Dori (1994) C-91/92, [1994] ECR I-3325

- TFEUart 288 there is no reason why a Regulation cannot do the same.

- European Social Charter 1961article 3. Oddly, the UK chose to express 28 days as 5.6 weeks in its own regulations (assuming a week is 5 working days).

- AG Slynn, the Court of Justice held that Ms Marshall, who was made to retire at 60 as a woman, unlike the men at 65, was unlawful sex discrimination, but only on the basis that the employer (the NHS) was the state. Obiter, at [48] the Court of Justice suggested she would not have succeeded if it were a 'private' party.

- (1948) per Vinson CJ at 19, 'These are not cases, as has been suggested, in which the States have merely abstained from action, leaving private individuals free to impose such discriminations as they see fit. Rather, these are cases in which the States have made available to such individuals the full coercive power of government to deny to petitioners, on the grounds of race or color, the enjoyment of property rights in premises which petitioners are willing and financially able to acquire and which the grantors are willing to sell'.

- Faccini Dori(1994) Case C-91/92, [1994] ECR I-3325

- ^ (1979) Case 148/78, [1979] ECR 1629

- ^ (1979) Case 148/78, [22]. See further in Barber (1990) C-262/88, AG van Gerven referred to the principle of nemo auditur propriam turpitudinem allegans, a civil law analogue of estoppel.

- ^ (1996) C-194/94, [1996] ECR I-2201, regarding Directive 83/189 which said various 'technical regulations' on alarm systems requiring approval from government.

- Pfeiffer v Deutsches Rotes Kreuz, Kreisverband Waldshut eV(2005) C-397/01, which found there could be no "horizontal" direct effect to claim against an employer that was a private ambulance service.

- ^ (1990) C-188/89, [1989] ECR 1839

- ^ Griffin v South West Water Services [1995] IRLR 15. This was not true for Doughty v Rolls-Royce [1991] EWCA Civ 15, but was for NUT v St Mary's School [1997] 3 CMLR 638.

- Paolo Faccini Dori v Recreb Srl(1994) Case C-91/92, [1994] ECR I-3325, holding Miss Dori could not rely on the Consumer Long Distance Contracts Directive 85/577/EEC, to cancel her English language course subscription in 7 days, but the Italian court had to interpret the law in her favour if it could.

- First Company Law Directive68/151/EEC

- ^ (1990) C-106/89. See also Von Colson v Land Nordrhein-Westfalen (1984) Case 14/83, [1984] ECR 1891, which held that because the member state had a choice of remedy, the Equal Treatment Directive did not allow Ms Van Colson to have a job as a prison worker.

- ^ Also, Grimaldi v Fonds des Maladies Professionnelles (1989) C-322/88, [1989] ECR 4407, [18] requires member state courts take account of Recommendations.

- ^ (1966) Case 61/65

- ^ (2011) C-196/09

- ^ See Court of Justice of the European Union, Annual Report 2015: Judicial Activity (2016)

- ^ Bulmer v Bollinger [1974] Ch 401

- ^ CPR 68.2(1)(a)

- ^ (1982) Case 283/81, [1982] ECR 3415, [16]

- ^ (2002) C-99/00

- ^ [2000] 3 CMLR 205

- Lord Toulsondissenting, would have held this charge, contrary to the requirement of good faith, created a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and duties. He pointed out that £85 was two-thirds of a state pension, and criticised the majority for wrongly applying the Court of Justice's case law.

- ^ Outright Monetary Transactions case (14 January 2014) BVerfGE 134, 366, 2 BvR 2728/13

- ^ cf Wilson v St Helens BC [1998] UKHL 37, [1999] 2 AC 52, per Lord Slynn on specific performance.

- ^ (1991) C-6/90 and C-9/90, [1991] ECR I-5357

- R (Factortame) v SS for Transport (No 3)(1996) C-46/93 and C-48/93, [1996] ECR I-1029

- ^ (1996) C-46/93 and C-48/93, [1996] ECR I-1029

- ^ (1996) C-46/93, [56]-[59]. Curiously, the German High Court, the Bundesgerichtshof, BGH, EuZW 1996, 761, eventually decided that the breach was not serious enough, though one might have read the Court of Justice to have believed otherwise.

- ^ Case C-224/01, [2003] ECR I-10239

- ^ P Laboratoires Pharmaceutiques Bergaderm and Goupil v Commission Case C-352/98, [2000] ECR I-5291

- ^ (1967) Case 8/66

- ^ (1967) Case 8/66, [91]

- ^ (2011) C-463/10P, [38] and [55]

- ^ (1981) Case 60/81

- ^ a b (1963) Case 25/62

- ^ Hartley 2014, p. 387.

- ^ (1985) Case 11/82, [9]

- ^ (1984) Case 222/83

- ^ (2002) C-50/00 P, AG Opinion, [60] and [103]

- ^ (2002) C-50/00 P, [38]-[45]

- ^ (2013) C-583/11

- ^ Compare, for example, the German Constitutional Court Act (Bundesverfassungsgerichtsgesetz) §90, which requires the probability that a claimant's human rights are infringed, or the Administrative Court Order (Verwaltungsgerichtsordnung) §42, which requires a probable infringement of a subjective right.

- ^ TEU art 6(2)

- L Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations(1953)

- ^ Internationale Handelsgesellschaft (1970) Case 11/70, [1970] ECR 1125

- ^ Nold v Commission (1974) Case 4/73, [1974] ECR 491

- ^ See above.

- ^ a b (2012) C-544/10

- ^ (2011) C-236/09

- ^ Regulation No 1924/2006 art 2(2)(5)

- ^ (2014) C-176/12

- R (Seymour-Smith) v Secretary of State for Employment[2000] UKHL 12 and (1999) C-167/97

- ^ See Mangold v Helm (2005) C-144/04 and Kücükdeveci v Swedex GmbH & Co KG (2010) C-555/07

- ^ See Eurostat, Table 1.

- ^ Treaty on European Union article 3(3), introduced by the Treaty of Lisbon. But see previously, Deutsche Post v Sievers (2000) C-270/97, 'the economic aim pursued by Article [157 TFEU] ..., namely the elimination of distortions of competition between undertakings established in different Member States, is secondary to the social aim pursued by the same provision, which constitutes the expression of a fundamental human right'. Defrenne v Sabena (1976) Case 43/75, [10] 'this provision forms part of the social objectives of the community, which is not merely an economic union, but is at the same time intended, by common action, to ensure social progress and seek the constant improvement of the living and working conditions of their peoples'.

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2015, ch 17.

- ^ Barnard 2013, ch 1, 3–30.

- (3rd 1821) ch 7

- B Balassa, The Theory of Economic Integration (1961)

- MJ Trebilcockand R Howse, The Regulation of International Trade (3rd edn 2005) ch 1, summarising and attempting to rebut various arguments.

- ^ Defrenne v Sabena (No 2) (1976) Case 43/75, [10]

- ^ White Paper, Completing the Internal Market (1985) COM(85)310

- TFEUart 30 is "intended to liberalize intra-Community trade or is it intended more generally to encourage the unhindered pursuit of commerce in individual Member States?"

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2015, ch 18–19.

- ^ Barnard 2013, chs 2–6.

- TFEUarts 28–30

- ^ (1974) Case 8/74, [1974] ECR 837

- TEECarticle 30.

- ^ See D Chalmers et al, European Union Law (1st edn 2006) 662, 'This is a ridiculously wide test.'

- Commission v Ireland (1982) Case 249/81

- Commission v France (1997) C-265/95. See further K Muylle, 'Angry famers and passive policemen' (1998) 23 European Law Review 467

- ^ PreussenElektra AG v Schleswag AG (2001) C-379/98, [2001] ECR I-2099, [75]-[76]

- ^ (2003) C-112/00, [2003] ECR I-5659

- ^ (2003) C-112/00, [79]-[81]

- AG Maduro, [23]-[25]

- ^ (2003) C-112/00, [2003] ECR I-5659, [77]. See ECHR articles 10 and 11.

- ^ Oebel (1981) Case 155/80

- ^ Mickelsson and Roos (2009) C-142/05

- ^ Vereinigte Familiapresse v Heinrich Bauer (1997) C-368/95

- Dansk Supermarked A/S(1981) Case 58/80

- ^ Barnard 2013, pp. 172–173.

- ^ (1979) Case 170/78

- TEECarticle 30

- ^ (1979) Case 170/78, [13]-[14]

- ^ (1983) Case 261/81

- ^ (1983) Case 261/81, [17]

- ^ (2003) C-14/00, [88]-[89]

- ^ (2009) C-110/05, [2009] ECR I-519

- ^ (2009) C-110/05, [2009] ECR I-519, [56]. See also Mickelsson and Roos (2009) C-142/05, on prohibiting jet skis, but justified if proportionate towards the aim of safeguarding health and the environment.

- ^ (1993) C-267/91

- ^ See also Torfaen BC v B&Q plc (1989) C-145/88, holding the UK Sunday trading laws in the former Shops Act 1950 were probably outside the scope of article 34 (but not clearly reasoned). The "rules reflect certain political and economic choices" that "accord with national or regional socio-cultural characteristics".

- ^ cf Vereinigte Familiapresse v Heinrich Bauer (1997) C-368/95

- ^ (1997) C-34/95, [1997] ECR I-3843

- ^ (2001) C-405/98, [2001] ECR I-1795

- Unfair Commercial Practices Directive 2005/29/EC

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2015, ch 21.

- ^ Barnard 2013, chs 8–9 and 12–13.

- ^ Craig, P; de Burca, G (2003). European Union Law. p. 701.

there is a tension 'between the image of the Community worker as a mobile unit of production, contributing to the creation of a single market and to the economic prosperity of Europe' and the 'image of the worker as a human being, exercising a personal right to live in another state and to take up employment there without discrimination, to improve the standard of living of his or her family

(This book is not listed on WorldCat, metadata is probably incorrect. - ^ Lawrie-Blum v Land Baden-Württemberg (1986) Case 66/85, [1986] ECR 2121

- ^ (1988) Case 196/87, [1988] ECR 6159

- ^ Dano v Jobcenter Leipzig (2014) C‑333/13

- ^ European Commission, 'The impact of free movement of workers in the context of EU enlargement' COM(2008) 765, 12, 'Practically of post-enlargement labour mobility on wages and employment of local workers and no indication of serious labour market imbalances through intra-EU mobility, even in those Member States with the biggest inflows'.

- ^ Angonese v Cassa di Risparmio di Bolzano SpA (2000) C-281/98, [2000] ECR I-4139

- Free Movement of Workers Regulation 492/2011arts 1–4

- ^ (1995) C-415/93

- ^ (1989) Case 379/87, [1989] ECR 3967

- ^ (2000) C-281/98, [2000] ECR I-4139, [36]-[44]

- ^ (1995) C-279/93

- ^ (2004) C-387/01, [54]-[55]

- ^ (2007) C-287/05, [55]

- ^ (2007) C-213/05

- ^ Hartmann v Freistaat Bayern (2007) C-212/05. Discussed in Barnard 2013, ch 9, 293–294

- ^ See Van Duyn v Home Office Case 41/74, [1974] ECR 1337

- ^ See NN Shuibhne, 'The Resilience of EU Market Citizenship' (2010) 47 CMLR 1597 and HP Ipsen, Europäisches Gemeinschaftsrecht (1972) on the concept of a 'market citizen' (Marktbürger).

- ^ Grzelczyk v Centre Public d'Aide Sociale d'Ottignes-Louvain-la-Neuve (2001) C-184/99, [2001] ECR I-6193

- JHH Weiler, 'The European Union belongs to its citizens: Three immodest proposals' (1997) 22 European Law Review 150

- ISSN 1572-8625.

- ^ 5th Report on Citizenship of the Union COM(2008) 85. The First Annual Report on Migration and Integration COM(2004) 508, found by 2004, 18.5m third country nationals were resident in the EU.

- CRD 2004 art 2(2) defines 'family member' as a spouse, long term partner, descendant under 21 or depednant elderly relative that is accompanying the citizen. See also Metock v Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform (2008) C-127/08, holding that four asylum seekers from outside the EU, although they did not lawfully enter Ireland (because their asylum claims were ultimately rejected) were entitled to remain because they had lawfully married EU citizens. See also, R (Secretary of State for the Home Department) v Immigration Appeal Tribunal and Surinder Singh[1992] 3 CMLR 358

- Communist Manifesto

- ^ (1998) C-85/96, [1998] ECR I-2691

- ^ (2004) C-456/02, [2004] ECR I-07573

- ^ (2001) C-184/99, [2001] ECR I-6193

- ^ (2005) C-209/03, [2005] ECR I-2119

- ^ (2005) C-147/03

- ^ (2014) C‑333/13

- ^ See Asscher v Staatssecretaris van Financiën (1996) C-107/94, [1996] ECR I-3089, holding a director and sole shareholder of a company was not regarded as a "worker" with "a relationship of subordination".

- ^ Craig & de Búrca 2015, ch 22.

- ^ Barnard 2013, chs 10–11 and 13.

- ^ (1995) C-55/94, [1995] ECR I-4165

- ^ Gebhard (1995) C-55/94, [37]

- TFEUart 54 treats natural and legal persons in the same way under this chapter.

- ITWF and Finnish Seamen's Union v Viking Line ABP and OÜ Viking Line Eesti(2007) C-438/05, [2007] I-10779, [34]

- ^ (1974) Case 2/74, [1974] ECR 631

- ^ See also Klopp (1984) Case 107/83, holding a Paris avocat requirement to have one office in Paris, though "indistinctly" applicable to everyone, was an unjustified restriction because the aim of keeping advisers in touch with clients and courts could be achieved by 'modern methods of transport and telecommunications' and without living in the locality.

- ^ (2011) C-565/08

- ^ (2011) C-565/08, [52]

- ^ Kamer van Koophandel en Fabrieken voor Amsterdam v Inspire Art Ltd (2003) C-167/01

- Employee Involvement Directive 2001/86/EC

- ^ (1988) Case 81/87, [1988] ECR 5483

- Überseering BV v Nordic Construction GmbH(2002) C-208/00, on Dutch minimum capital laws.

- Brandeis Jand W Cary, 'Federalism and Corporate Law: Reflections on Delaware' (1974) 83(4) Yale Law Journal 663. See further S Deakin, 'Two Types of Regulatory Competition: Competitive Federalism versus Reflexive Harmonisation. A Law and Economics Perspective on Centros' (1999) 2 CYELS 231.

- ^ (2002) C-208/00, [92]-[93]

- ^ (2008) C-210/06

- ^ See further National Grid Indus (2011) C-371/10 (an exit tax for a Dutch company required justification, not justified here because it could be collected at the time of transfer) and VALE Epitesi (2012) C-378/10 (Hungary did not need to allow an Italian company to register)

- business lawpolicies, have brought about other corporate law changes in Europe that were neither intended by the Court nor by policy-makers"

- TFEUarts 56 and 57

- ^ (1974) Case 33/74

- ^ cf Debauve (1980) Case 52/79, art 56 does not apply to 'wholly internal situations' where an activity are all in one member state.

- ^ Belgium v Humbel (1988) Case 263/86, but contrast Schwarz and Gootjes-Schwarz v Finanzamt Bergisch Gladbach (2007) C-76/05

- ^ Wirth v Landeshauptstadt Hannover (1993) C-109/92

- ^ (2001) C-157/99, [2001] ECR I-5473

- ^ (2001) C-157/99, [48]-[55]

- ^ (2001) C-157/99, [94] and [104]-[106]

- ^ See Watts v Bedford Primary Care Trust (2006) C-372/04 and Commission v Spain (2010) C-211/08

- ^ (2010) C‑137/09, [2010] I-13019

- ^ (1995) C-384/93, [1995] ECR I-1141

- ^ (2004) C-36/02, [2004] ECR I-9609

- ^ (2009) C‑42/07, [2007] ECR I-7633

- ^ "Directive 2006/123/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on services in the internal market". 27 December 2006.

- J Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality(2011) ch 9 and 349

- ^ Capital Movement Directive 1988 (88/361/EEC) Annex I, including (i) investment in companies, (ii) real estate, (iii) securities, (iv) collective investment funds, (v) money market securities, (vi) bonds, (vii) service credit, (viii) loans, (ix) sureties and guarantees (x) insurance rights, (xi) inheritance and personal loans, (xii) physical financial assets (xiii) other capital movements.

- ^ (2000) C-251/98, [22]

- ^ e.g. Commission v Belgium (2000) C-478/98, holding that a law forbidding Belgian residents getting securities of loans on the Eurobond was unjustified discrimination. It was disproportionate in preserving, as Belgium argued, fiscal coherence or supervision.

- ^ See Commission v United Kingdom (2001) C-98/01 and Commission v Netherlands (2006) C‑282/04, AG Maduro's Opinion on golden shares in KPN NV and TPG NV.

- ^ (2007) C-112/05

- ^ (2010) C-171/08

- ^ TFEU art 345

- ^ See Delors Report, Report on Economic and Monetary Union in the EC (1988)

- J Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality(2011) ch 9 and 349

- RB Reich, Saving Capitalism: for the many not the few (2015) chs 2, 4–7 and 21

- S Deakin and F Wilkinson, 'Rights vs Efficiency? The Economic Case for Transnational Labour Standards' (1994) 23(4) Industrial Law Journal 289

- TFEUarts 101–109 and 145–172.

- ^ (1976) Case 43/75, [10]

- ^ See Louis K. Liggett Co. v. Lee, 288 U.S. 517 (1933)

- (1970)

- TFEU article 102"is aimed not only at practices which may cause prejudice to consumers directly, but also at those which are detrimental to them through their impact on an effective competition structure".

- TFEU art 169

- CFREU art 38

- ^ a b See Banco Español de Crédito SA v Camino (2012) Case C-618/10, [39] and Océano Grupo Editorial and Salvat Editores (2000) C-240/98 to C-244/98 and [2000] ECR I-4941, [25]

- ^ Product Liability Directive 1985 85/374/EEC, recital 1 and 6

- ^ PLD 1985 arts 1 and 3

- H Collins, 'Good Faith in European Contract Law' (1994) 14 OJLS 229

- ^ Banco Español de Crédito SA v Camino (2012) Case C-618/10

- ^ See further, for the history behind the parallel in German contract law, BGB §307 Münchener Kommentar zum Bürgerlichen Gesetzbuch §307 Rn 32

- RWE AG v Verbraucherzentrale NRW eV (2013) C-92/11

- ^ (2013) C-488/11

- ^ (2013) Case C-415/11

- ^ (2014) Case C-34/13

- TFEU art 147

- TFEU art 153(1)

- S Deakinand F Wilkinson, The Law of the Labour Market (2005) 90.

- ^ See the Charter's text

- European Social Charter 1961 art 2(1)

- WTD 2003 art 7, referring to "four weeks" and arts 5 and 6 referring to the concept of "weekly" as meaning a "seven-day period". The choice to phrase time off as "weeks" was interpreted by the UK Supreme Court to mean employees have the right to take weeks off at a time, rather than separate days in the UK context: Russell v Transocean International Resources Ltd [2011] UKSC 57, [19]

- JM Keynes, Economic Possibilities of our Grandchildren (1930) arguing a 15-hour week was achievable by 2000 if gains in productivity increases were equitably shared.

- Institutions for Occupational Retirement Provision Directive 2003 arts 11–12, 17–18

- ^ e.g. Pensions Act 2004 ss 241–243

- European Social Charter 1961art 2(1).

- WTD 2003 art 7. In the UK, the implementing Working Time Regulations 1998state "5.6 weeks" is needed, although this is also 28 days, as a "week" was originally taken to refer to a 5-day working week.

- WTD 2003 arts 2–5 and 8–13

- Pfeiffer v Deutsches Kreuz, Kreisverband Waldshut eV (2005) C-397/01

- ^ Boyle v Equal Opportunities Commission (1998) C-411/96 requires pay be at least the same level as statutory sick pay.

- Safety and Health at Work Directive 1989 art 11

- ^ See also the Health and Safety of Atypical Workers Directive 1991 extends these protections to people who do not have typical, full-time or permanent employment contracts.

- ^ (2010) C-555/07

- ^ ECHR art 11. This codified traditions in democratic member states before World War II. See for example Crofter Hand Woven Harris Tweed Co Ltd v Veitch [1941] UKHL 2

- ^ [2002] ECHR 552

- ^ [2008] ECHR 1345

- Demir and Baykara v Turkey [2008] ECHR 1345

- ^ See further Enerji Yapi-Yol Sen v Turkey (2009) Application No 68959/01

- ^ (2007) C-438/05

- ^ (2007) C-319/05, and C-319/06

- ^ e.g. The Rome I Regulation

- ^ (1991) C-6/90

- ^ Statute for a European Company Regulation 2001 No 2157/2001

- ^ Statute for a European Company Regulation 2001 art 3

- ^ Employee Involvement Directive 2001 Annex

- ^ See for example, BCE Inc v 1976 Debentureholders [2008] 3 SCR 560

- ^ See the Thirteenth Company Law Directive 2004 2004/25/EC

- Insolvency Regulation (EC) 1346/2000

- Centros Ltd v Erhversus-og Selkabssyrelsen(1999) C-212/97

- ^ Kamer van Koophandel en Fabrieken voor Amsterdam v Inspire Art Ltd (2003) C-167/01

- ^ Other People's Money And How the Bankers Use It (1914) and E McGaughey, 'Does Corporate Governance Exclude the Ultimate Investor?' (2016) 16(1) Journal of Corporate Law Studies 221

- ^ See M Gold, 'Worker directors in the UK and the limits of policy transfer from Europe since the 1970s' (2005) 20 Historical Studies in Industrial Relations 29, 35

- Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act 2010 §957, inserting Securities Exchange Act 1934§6(b)(10)

- Institutions for Occupational Retirement Provision Directive 2003 2003/41/EC

- UCITS Directive 2009 art 19(3)(o)

- (1932) Part III

- ^ UCITS V Directive 2014/91/EU

- ^ 2004/39/EC, art 18 on conflicts of interest

- ^ 2011/61/EU art 3(2)

- ^ 2011/61/EU respectively arts 22–23, 13 and Annex II, 14 and 30

- ^ "EUR-Lex - 32009L0138 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu.

- ^ (2004) Case T-201/04, [1052]

- social progress, and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment".

- ^ Höfner and Elser v Macrotron GmbH (1991) C-41/90

- ^ See Federación Española de Empresas de Tecnología Sanitaria (FENIN) v Commission (2003) T-319/99

- TFEU art 49 distinguishes the right of establishment for "self employed persons" from the right "to set up and manage undertakings". Transfers of Understakings Directive 2001/23/EC art 1(b) defines an "economic entity" as an "organised grouping of resources". Contrast FNV Kunsten Informatie en Media v Staat der Nederlanden (2014) C-413/13 and clarification that solo-self-employed persons will not be subject to competition law in Communication from the commission Guidelines on the application of Union competition law to collective agreements regarding the working conditions of solo self-employed persons 2022/C 374/02

- article 11, freedom of association subject only to proportionate restrictions in a democracy.

- ^ Wouters v Algemene Raad van de Nederlandsche Orde van Advocaten (2002) C-309/99, [2002] ECR I-1577

- ^ Meca Medina and Majcen v Commission (2006) C-519/04 P, [2006] ECR I-6991.

- ^ See Societe Technique Miniere v Maschinenbau Ulm GmbH [1996] ECR 234, [249] and Javico International and Javico AG v Yves Saint Laurent Parfums SA [1998] ECR I-1983, [25]

- ^ See Courage Ltd v Crehan (2001) C-453/99, "the matters to be taken into account... include the economic and legal context... and... the respective bargaining power and conduct of the two parties to the contract".

- ^ AKZO Chemie BV v Commission (1991) C-62/86, [60]. Cf. Hoffmann-La Roche & Co. AG v Commission (1979) Case 85/76, [41]: 'very large shares are in themselves... evidence of... a dominant position'.

- ^ British Airways plc v Commission (2003) T-219/99, [211], [224]–[225], given the nearest rival only had a 5.5% market share.

- ^ Società Italiana Vetro SpA v Commission (1992) T-68/89, [358]. Compagnie Maritime Belge Transports SA v Commission (2000) C-395/96, [41]–[45].

- ^ Viho Europe BV v Commission (1996) C-73/95, [16].

- ^ Europemballage Corp. and Continental Can Co. Inc. v Commission (1973) Case 6/72, [26], list in treaties 'not an exhaustive enumeration'.

- United Brands Co v Commission(1978) Case 27/76, [250]–[252].

- ^ COMP/C-1/36.915, Deutsche Post AG – Interception of cross-border mail (25 July 2001) para 166.

- ^ AKZO Chemie BV v Commission (1991) C-62/86, [71]–[72]

- ^ France Telecom SA v Commission (2009) C-202/07

- ^ (2012) C-457/10 P, [98] and [132].

- ^ a b T-604/18

- ^ (1974) Cases 6-7/73

- ^ (2004) Case T-201/04

- ^ British Airways plc v Commission (2007) C-95/04, [68]

- ^ (2004) Case T-201/04

- ^ (2017) C-413/14, (2022) T-286/09 RENV

- Merger Regulation 2004 139/2004/ECarts 1 and 2(3)

- ^ e.g. Tetra Laval BV v Commission (2002 T-5/02, [155]

- ^ e.g. M Bajgar, G Berlingieri, S Calligaris, C Criscuolo and J Timmis, 'Industry Concentration in Europe and North America' (January 2019) OECD Productivity Working Paper No. 18, 2

- ^ (2014) C-434/13

- ^ e.g. ICI Ltd v Commission (1972) Cases 48–57/69, [66]

- ^ CECED [2000] OJ L187/47, [48]–[51]. Also Philips/Osram [1994] OJ L378/37.

- ^ See further H Collins, The European Civil Code: The Way Forward (2009)

- ^ Brussels I Regulation 2012 1215/2012

- ^ Rome I Regulation (EC) 593/2008 arts 3 and 8

- ^ Rome II Regulation (EC) No 864/2007

- ^ Copyright Term Directive 2006 2006/116/EC art 1

- Copyright and Information Society Directive (2001/29)

- ^ 2015/2436

- ICESCR 1966 art 13(2)(c). cf in the UK, the Higher Education Act 2004 ss 23-24 and 31-39 (tuition fees and plans) and Higher Education (Higher Amount) Regulations 2010regs 4-5A.

- ^ For and example, see the French Education Code, arts L712-1 to 7 (governing bodies) and Higher Education Law (2019) art 90 (academic council powers). Compare the Oxford University Statute IV and VI, Council Regulations 13 of 2002, regs 4-10 (majority-elected Council, tracing back to Oxford University Act 1854 ss 16 and 21) and Higher Education Governance (Scotland) Act 2016 ss 10 and 18.

- UDHR 1948 art 26"free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages" and "higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit."

- CFREU 2000 art 14.

- ^ W Rüegg et al, A History of the University in Europe (1992) vol 1, 'Universities in the Middle Ages'

- ^ See further S Garben, EU Higher Education Law. The Bologna Process and Harmonization by Stealth (2011)

- ^ Commission v Austria (2005) C-147/03, higher requirements for non-Austrians (mainly Germans) were held invalid despite the alleged 'structural, staffing and financial problems'. Commission v Belgium (2004) C-65/03, held invalid Belgian university limits on foreign (mainly French) students.

- ^ See H Skovgaard-Petersen, 'There and back again: portability of student loans, grants and fee support in a free movement perspective' (2013) 38(6) European Law Review 783

- ^ R (Bidar) v London Borough of Ealing (2005) C-209/03, under TFEU arts 18-21.

- ^ France Education Code, arts L712-1 to 7

- ^ French Higher Education Law (2019) art 90

- ^ L Crehan, Cleverlands: The Secrets Behind the Success of the World's Education Superpowers (2011)

- ECHR 1950arts 2, 3 and 8 (right to life)

- NHS Act 2006s 43A.

- ^ See Germany, Sozialgesetzbuch V, §§1-6, 12, 20 and 138. 'Germany: Health system review' (2020) 22(6) HSiT 1, 30-49

- Patients' Rights Directive 2011/24/EU arts 4-8

- ^ See EHIC Decision 2003/751/EC, No 189

- ^ [2008] ECHR 453

- ^ D v United Kingdom (1997) 24 EHRR 423

- ICESCR 1966 art 7. E McGaughey, Principles of Enterprise Law: the Economic Constitution and Human Rights (Cambridge UP 2022) ch 10

- ^ TFEU art 131

- ^ TFEU art 283(2)

- ^ European Central Bank Statute arts 10-11

- TFEU art 282 and TEUart 3(3)

- 2021–2022 global energy crisis

- argues that the price stability objective cannot be interpreted in a way that conflicts with general EU goals.

- ^ Statute of the European Central Bank art 19

- ^ Statute of the European Central Bank art 18.1

- ^ (2015) C-62/14, [103]-[105]

- Credit Institutions Directive 2013/36/EUarts 8-18, 35, 88-96

- Capital Requirements Regulation (EU) No 575/2013arts 114-134

- Deposit Guarantee Directive 2014/49/EU

- Doughnut Economics(2017)

- ^ See the Multilateral Financial Framework Regulation 2020/2093 Annex I

- Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union arts 3-4

- ^ Pringle v Government of Ireland (2012) C‑370/12 held the mechanism lawful despite a challenge that it exceeded the EU's competence for economic policy.

- Gross National Income Regulation (EU) 2019/516 arts 1-2. See previously GDP Directive 89/130/EEC, now repealed.

- EU tax haven blacklist

- ECHR 1950art 2. ICCPR 1966 art 6(1)

- CFREU 2000 art 37

- TFEU art 3(3)"improvement of the environment"

- TFEU art 194, requiring a functioning energy market, security of supply, energy efficiency and 'new and renewable forms of energy', and network interconnection. Such measures shall not affect a Member State's right to determine the conditions for exploiting its energy resources, its choice between different energy sources and the general structure of its energy supply, without prejudice to Article 192(2)(c)" which in turn requires unanimity for "measures significantly affecting a Member State's choice between different energy sources and the general structure of its energy supply." This does not prevent measures to make energy sources internalise pollution costs in full.

- UDHR 1948 arts 3 and 27(1). ICESCR 1966 art 15. On origins, see L Shaver, 'The right to science and culture' [2010] Wisconsin Law Review 121.

- ^ Climate Neutral Communication COM/2020/562

- Renewable Energy Directive (EU) 2018/2001arts 3, 7, Annexes I and V (32% renewable target)

- ^ 'Parliament backs boost for renewables use and energy savings' (14 September 2022) europarl.europa.eu

- ^ RePowerEU Communication COM(2022) 108 final

- Hydrocarbons Directive 94/22/ECarts 2-6

- ^ e.g. M Roser, 'Why did renewables become so cheap so fast?' (1 December 2020) Our World in Data

- ^ E McGaughey, Principles of Enterprise Law: the Economic Constitution and Human Rights (Cambridge UP 2022) ch 11, 411-414

- ICCPR 1966articles 6 and 17

- Friends of the Earth v Royal Dutch Shell plc(26 May 2021) C/09/571932 / HA ZA 19-379

- ^ T Wilson, 'Shell investors back moving HQ from Netherlands to UK' (10 December 2021) Financial Times

- ^ A Elfar, 'Landmark Climate Change Lawsuit Moves Forward as German Judges Arrive in Peru' (4 August 2022) Columbia Climate School, appealing from the Regional Court (2015) Case No. 2 O 285/15.

- ^ Judgment (20 December 2019) 19/00135

- ^ Klimaschutz or Climate Change case (24 March 2021) 1 BvR 2656/18

- ^ Compare the Environmental Liability Directive 2004 (2004/35/EC) which requires polluters pay for damage and take remedial action for species and habitats as defined in the Birds Directive 2009/147/EC arts 2 and 4, duty to protect birds, and Habitats Directive 92/43/EC

- ^ See 'Weekly European Union Emission Trading System (EU-ETS) carbon pricing in 2022' (13 December 2022) Statistia

- ^ a b Renewable Energy Directive 2018 art 2(a) and (e) and Annex V

- ^ M Le Page, 'The Great Carbon Scam' (21 September 2016) 231 New Scientist 20–21. M Norton et al, 'Serious mismatches continue between science and policy in forest bioenergy' (2019) 11(1) GCB Bioenergy 1256. T Searchinger et al, 'EU climate plan sacrifices carbon storage and biodiversity for bioenergy' (28 November 2022) 612 Nature 27, "the EU's "own modeling predicts that yearly use of bioenergy will more than double between 2015 and 2050, from 152 million to 336 million tonnes of oil equivalent. That requires a quantity of biomass each year that is twice Europe's present annual wood harvest."

- ^ (2001) C-379/98, [62], following the Opinion of Advocate General Jacobs.

- ^ Electricity Directive 2019/944 2019/944 art 8 and the Gas Directive 2009/73/EC art 4.

- ^ Electricity Directive 2019/944 art 35 and the Gas Directive 2009/73/EC art 9

- ^ Electricity Directive 2019/944 arts 3 and 6.

- Netherlands v Essent (2013) C-105/12, [4]

- ^ (2013) C-105/12, [66]

- ^ Costa v ENEL (1964) Case 6-64

- ^ Foster v British Gas plc (1990) C-188/89, [22]

- ^ M Florio, 'The Return of Public Enterprise' (2014) Working Paper N. 01/2014, 7-8. Also R Brau, R Doronzo, C Fiorio and M Florio, 'EU gas industry reforms and consumers' prices' (2010) 31(4) Energy Journal 163.

- ^ Draft Energy Price Regulation COM/2022/473 final

- ^ e.g. in the German state of North Rhine Westfalia, see Gemeindeordnung Nordrhein-Westfalen 1994 §§107-113

- ^ UDHR 1948 art 25(1). ICESCR 1966 art 11(1). UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2002) General Comment No.15, water implicit in right to food.

- TFEUarts 4 (shared competence for agriculture and environment), 13 (pay regard to animal welfare)

- ^ JC Bureau and A Matthews, 'EU Agricultural Policy: What Developing Countries Need to Know' (2005) IIS Discussion Paper No 91, 3. E McGaughey, Principles of Enterprise Law: the Economic Constitution and Human Rights (Cambridge UP 2022) ch 13

- ^ 'Farmers and the agricultural labour force - statistics' (November 2022)

- TFEU arts 38-44, and art 39on CAP objectives.

- ^ Management and Financing Regulation (EU) No 1306/2013 art 4

- ^ Direct Payments Regulation (EU) No 1307/2013 arts 9 and 33

- ^ DPR 2013 arts 10 and Annex IV. Wachauf v Federal Republic of Germany (1989) Case 151/78 held that milk subsidies are a type of property and a real asset that could not simply be withdrawn without compensation.

- ^ DPR 2013 arts 10-11 and 32

- ^ Management and Financing Regulation (EU) No 1306/2013 arts 91-101

- ^ DPR 2013 arts 45

- ^ Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC and the Wild Birds Directive 2009/147/EC

- ^ Agricultural Products Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 art 8

- Agricultural Unfair Trading Practices Directive 2019/633 art 3

- ^ Management and Financing Regulation (EU) No 1306/2013 arts 4-5

- ^ Rural Development Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 arts 3, 7-9, 17 and 19

- ^ RDR 2013 art 5

- ^ Cheminova A/S v Commission [2009] ECR II-02685

- ^ JO Kaplan et al, 'The prehistoric and preindustrial deforestation of Europe' (2009) 28 Quaternary Science Reviews 3016

- ^ Land Use and Forestry Directive 2018 2018/841 arts 1-4

- Timber Regulation (EU) No 995/2010arts 3-6

- Water Framework Directive 2000/60/ECarts 4-9

- ^ Drinking Water Quality Directive 2020/2184, arts 4-5 and Annex

- Bathing Waters Directive 2006/7/ECarts 3-5

- ^ (1992) C-337/89, on Water Industry Act 1991 ss 18-19

- ^ e.g. Commission v Spain (2003) C-278/0, confirming fines of €624,150 a year and per 1% of bathing areas in Spanish inshore waters which were found unclean.

- CFREU 2000arts 27 and 36

- ICESCR 1966 art 15(1)(b)

- ^ Renewable Energy Directive 2018/2001 arts 25 and 27. RED 2009, article 3(4) required at least 10% of transport was fueled from renewable energy by 2020.

- ^ Renewable Energy Directive 2018/2002 art 3(1). The previous target was 15% by 2020.

- ^ 'EU ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2035 explained' (3 November 2022) europarl.europa.eu

- J Armour, 'Volkswagen's Emissions Scandal: Lessons for Corporate Governance?' (2016) OxBLB pt 1, 2.

- ^ Emission Performance Regulation 2019/631 arts 1(2) and 2, previously 120 grams of CO2 per km.

- ^ EPR 2019 art 6

- ^ EPR 2019 arts 7-10. Also art 11 derogations.

- ^ Vehicle Emissions Regulation (EC) 715/2007 Annex, sets out the Euro 6 limits. See summary in 'EU: Light-Duty: Emissions' and 'EU: Heavy-Duty: Emissions' (2021) transportpolicy.net

- ^ Heavy Vehicle Emission Regulation (EU) 2019/1242 arts 4-5, the Commission determining limits ad hoc, and a zero-emission vehicle counting as two.

- J Armour, 'Volkswagen's Emissions Scandal: Lessons for Corporate Governance?' (2016) OxBLB pt 1, 2, in 2014, the year that VW fraud was first alleged, Winterkorn was paid €18 million, of which €16 million was 'performance based' variable pay.

- ^ Trans-European transport network Regulation, COM(2021) 812 final and European Court of Auditors Report (2018)

- ^ Driving Licenses Directive 2006/126/EC

- ^ Road Transport Regulation (EC) No. 561/2006 arts 4 and 6

- ^ Asociación Profesional Élite Taxi v Uber Systems Spain SL (2017) C-434/15

- ^ Bus Passenger Rights Regulation 2011 (EU) No 181/2011 art 2.

- ^ e.g. 'Electric Dreams: Green Vehicles Cheaper Than Petrol' (29 June 2020) Direct Line Group

- ^ Single European Railway Directive 2012/34/EU arts 4 and 7. This followed the First Railway Directive 91/440/EC.

- Single European Railway Directive 2012/34/EUart 5-6

- ^ Passenger Rights Regulation 2007 (EC) No 1371/2007 art 3 (bikes), 8-9 (information and tickets)