European maritime exploration of Australia

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

|

|

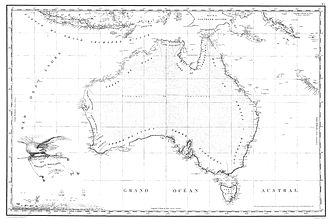

The maritime European exploration of Australia consisted of several waves of European seafarers who sailed the edges of the

The most famous expedition was that of

Pro-Iberian hypotheses and theories

Some writers have advanced the theory that the Portuguese were the first Europeans to sight Australia in the 1520s.[1][2]

A number of relics and remains have been interpreted as evidence that the Portuguese reached Australia. The primary evidence advanced to support this theory is the representation of the continent of Jave la Grande, which appears on a series of French world maps, the Dieppe maps, and that may, in part, be based on Portuguese charts. However, most historians do not accept this theory, and the interpretation of the Dieppe maps is highly contentious.[3][4][5][6][7] In the early 20th century, Lawrence Hargrave argued that Spain had established a colony in Botany Bay in the 16th century.[8] Five coins from the Kilwa Sultanate were found on Marchinbar Island, in the Wessel Islands in 1945 by RAAF radar operator Morry Isenberg. In 2018 another coin, also thought to be from Kilwa, was found on a beach on Elcho Island, another of the Wessel Islands, by archaeologist and member of the Past Masters, Mike Hermes. Hermes speculated that the coins may suggest trade between indigenous Australians and Kilwa, or may have arrived via Makassan contact with Australia. Mike Owen, another member of the Past Masters group speculated that these coins may have arrived sometime after they had installed Muhammad Arcone on the Kilwa throne as a Portuguese vassal, from 1505 to 1506, or that the Portuguese had visited Wessel islands.[9]

The French navigator Binot Paulmier de Gonneville[10] claimed to have landed at a land he described as "east of the Cape of Good Hope" in 1504, after being blown off course. For some time it had been thought he landed in Australia, but the place he landed has now been shown to be Brazil (which is north-west of the Cape).[11]

17th century

Dutch exploration

The most significant exploration of Australia in the 17th century was by the Dutch. The Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, "VOC", "United East India Company") was set up in 1602 and traded extensively with the islands which now form parts of Indonesia, and hence were very close to Australia already.

The first documented and undisputed European

That same year, a Spanish expedition sailing in nearby waters and led by

In 1611

In 1619

Hessel Gerritsz was appointed on 16 October 1617 as the first exclusive cartographer of VOC, whose job included creating and maintaining charts of coastlines in the area. Gerritsz produced a map in 1622 which showed the first part of Australia to be charted, that by Janszoon in 1606.[25] It was considered to be part of New Guinea and called Nueva Guinea on the map, but Gerritsz also added an inscription saying:

- "Those who sailed with the yacht of Pedro Fernandes de Queirós in the neighbourhood of New Guinea to 10 degrees westward through many islands and shoals and over 2, 3 and 4 fathoms for as many as 40 days, presumed that New Guinea did not extend beyond 10 degrees to the south. If this be so, then the land from 9 to 14 degrees would be a separate land, different from the other New Guinea".[26][27][28]

All charts and logs from returning VOC merchants and explorer sailors had to be submitted to Gerritsz and provided new information for several breakthrough maps which came from his hands. Gerritsz' charts would accompany all VOC captains on their voyages. In 1627 Gerritsz made a map, the Caert van't Landt van d'Eendracht, entirely devoted to the discoveries of the West Australian coastline, which was named "Eendrachtsland", though the name had been used since 1619.

On 1 May 1622, Englishman

In 1623,

In 1627, François Thijssen ended up too far south and on 26 January 1627 he came upon the coast of Australia, near Cape Leeuwin, the most south-west tip of the mainland. Pieter Nuyts the VOC official aboard his ship gave Thijssen permission to continue to sail eastwards, mapping more than 1,500 kilometres (930 mi) of the southern coast of Australia from Albany, Western Australia to Ceduna, South Australia. He called the land 't Land van Pieter Nuyts ("The Land of Pieter Nuyts"). Part of Thijssen's map shows the islands St Francis and St Peter, now known collectively with their respective groups as the Nuyts Archipelago. Thijssen's observations were included as early as 1628 by Gerritsz in a chart of the Indies and Eendrachtsland

One Dutch captain of this period who was not really an explorer but who nevertheless bears mentioning was Francisco Pelsaert, captain of the Batavia, which was wrecked off the coast of Western Australia in 1629.[32]

In August 1642, VOC despatched Abel Tasman and Franchoijs Visscher on a voyage of which one of the objects was to obtain knowledge of "all the totally unknown provinces of the

In 1644 Tasman made a second voyage with three ships (Limmen, Zeemeeuw, and the tender Braek). He followed the south coast of New Guinea eastwards, missed the Torres Strait between New Guinea and Australia, and continued his voyage westwards along the north Australian coast. He mapped the north coast of Australia making observations on the land, which he called New Holland, and its people. From the point of view of the Dutch East India Company, Tasman's explorations were a disappointment: he had found neither a promising area for trade nor a useful new shipping route.[34]

By the end of the Renaissance (1450 to 1650),[35] every continent had been visited and mostly mapped by Europeans, except the south polar continent now known as Antarctica, but originally called Terra Australis, or 'Australia' for short.[36] This geographical achievement was displayed on the large world map Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula made by the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu in 1648 to commemorate the Peace of Westphalia.

A map of the world inlaid into the floor of the Burgerzaal ("

Maps from this period and the early 18th century often have Terra Australis or t'Zuid Landt ("the South Land") marked as "New Holland", the name given to the continent by Abel Tasman in 1644.[40][41] Joan Blaeu's 1659 map shows the clearly recognizable outline of Australia based on the many Dutch explorations of the first half of the 17th century.

In 1664, the French geographer

| When | Who | Ship(s) | Where |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1606 | Willem Janszoon | Duyfken | Gulf of Carpentaria, Cape York Peninsula (Queensland) |

| 1616 | Dirk Hartog | Eendracht

|

Shark Bay area, Western Australia |

| 1619 | Frederick de Houtman[47] and Jacob d'Edel | Amsterdam

|

Sighted land near Perth, Western Australia |

| 1623 | Jan Carstensz[48] | Pera and Arnhem | Gulf of Carpentaria, Carpentier River |

| 1627 | François Thijssen[49] | het Gulden Zeepaerdt | 1800 km of the South coast (from Cape Leeuwin to Ceduna) |

| 1642–1643 | Abel Tasman | Heemskerck and Zeehaen | Van Diemen's Land, later called Tasmania |

| 1696–1697 | Willem de Vlamingh[50] | Geelvink, Nyptangh and the Wezeltje | Rottnest Island, Swan River, Dirk Hartog Island (Western Australia) |

In 1696,

Others

Englishman William Dampier came looking for the Tryall in 1688, 66 years after it was wrecked. Dampier was the first Englishman to set foot on the Australian mainland on 5 January 1688, when his ship the Cygnet was marooned in King Sound. While the ship was being careened he made notes on the fauna and flora and the indigenous peoples he found there. He made another voyage to the region in 1699, before returning to England. He described some of the flora and fauna of Australia, and was the first European to report Australia's peculiar large hopping animals. Dampier contributed to knowledge of Australia's coastline through his two-volume publication A Voyage to New Holland (1703, 1709). His book of adventures, A New Voyage around the World, created a sensation when it was published in English in 1697.[51] Though he was briefly marooned on the northwest Australian coast on the trip described in this book, only his second voyage seems to be of importance to Australian exploration.

18th century

In 1756, French King Louis XV sent Louis Antoine de Bougainville to look for the Southern lands. After a stay in South America and the Falklands, Bougainville reached Tahiti in April 1768, where his boat was surrounded by hundreds of canoes filled with beautiful women. "I ask you", he wrote, "given such a spectacle, how could one keep at work 400 Frenchmen?" He claimed Tahiti for the French and sailed westward, past southern Samoa and the New Hebrides, then on sighting Espiritu Santo turned west still looking for the Southern Continent. On June 4 he almost ran into heavy breakers and had to change course to the north and east. He had almost found the Great Barrier Reef. He sailed through what is now known as the Solomon Islands that, due to the hostility of the people there, he avoided, until his passage was blocked by a mighty reef. With his men weak from scurvy and disease and no way through he sailed for Batavia in the Dutch East Indies where he received news of Wallis and Carteret who had preceded Bougainville. When he returned to France in 1769, he was the first Frenchman to circumnavigate the globe and the first European known to have seen the Great Barrier Reef. Though he did not reach the mainland of Australia, he did eliminate a considerable area where the Southern land was not.

In the meantime, in 1768, British Lieutenant James Cook was sent from England on an expedition to the Pacific Ocean to observe the transit of Venus from Tahiti, sailing westwards in HMS Endeavour via Cape Horn and arriving there in 1769. On the return voyage he continued his explorations of the South Pacific, in search of the postulated continent of Terra Australis. He first reached New Zealand, and then sailed further westwards to sight the south-eastern corner of the Australian continent on 20 April 1770. In doing so, he was to be the first documented European expedition to reach the eastern coastline of Australia. He continued sailing northwards along the east coast, charting and naming many features along the way. He identified Botany Bay as a good harbour and one potentially suitable for a settlement, and where he made his first landfall on 29 April. Continuing up the coastline, the Endeavour was to later run aground on shoals of the Great Barrier Reef (near the present-day site of Cooktown), where she had to be laid up for repairs. The voyage then recommenced, eventually reaching the Torres Strait. At Possession Island Cook formally claimed possession of the entire east coast he had just explored for Britain.[52] The expedition returned to England via the Indian Ocean and Cape of Good Hope.[53]

In 1772, two French expeditions set out to find Terra Australis. The first was led by

Cook's first expedition carried botanist

Just as he was attempting to move the colony, on 24 January 1788 Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse arrived off Botany Bay.[59][60][61] The French expedition consisted of two ships led by La Pérouse, the Astrolabe and the Boussole, which were on the latest leg of a three-year voyage that had taken them from Brest, around Cape Horn, up the coast from Chile to California, north-west to Kamchatka, south-east to Easter Island, north-west to Macao, and on to the Philippines, the Friendly Isles, Hawaii and Norfolk Island.[62] The gale also prevented La Pérouse's ships from entering Botany Bay. Though amicably received, the French expedition was a troublesome matter for the British, as it showed the interest of France in the new land. To preempt a French claim to Norfolk Island, Phillip ordered Lieutenant Philip Gidley King to lead a party of 15 convicts and seven free men to take control of Norfolk Island. They arrived on 6 March 1788, while La Pérouse was still in Sydney.

The British received him courteously, and each captain, through their officers, offered the other any assistance and needed supplies.

In September 1791, the French Assembly decided to send an expedition in search of La Pérouse, and

| When | Captain | Ship(s) | Where |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1770 | James Cook | HMS Endeavour | East coast of Australia |

| 1773 | Tobias Furneaux [71] | HMS Adventure | South and east coasts of Tasmania |

| 1776 | James Cook | HMS Resolution | Southern Tasmania |

| 1788 | Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse | Astrolabe and Boussole | Botany Bay, New South Wales (encountered "First Fleet") |

Later exploration from the sea

In 1796 (after settlement), British Matthew Flinders with George Bass took a small open boat, the Tom Thumb 1, and explored some of the coastline south of Sydney. He suspected from this voyage that Tasmania was an island, and in 1798 Bass and he led an expedition to circumnavigate it and hence prove his theory. The sea between mainland Australia and Tasmania was named Bass Strait. One of the two major islands in Bass Strait was later named Flinders Island by Philip Parker King. Flinders returned to England in 1801.

Meantime, in October 1800, Frenchman

Flinders' work came to the attention of many of the scientists of the day, in particular the influential

Investigator set sail for New Holland on 18 July 1801. Attached to the expedition was the

While each was charting Australia's coastline, Baudin and Flinders met by chance in April 1802 in Encounter Bay in what is now South Australia. Baudin stopped at the settlement of Sydney for supplies. In Sydney he bought a new ship, the Casuarina, a smaller vessel which could conduct close inshore survey work, under the command of Louis de Freycinet. He sent home the larger Naturaliste with all the specimens that had been collected by Baudin and his crew. He then headed for Tasmania and conducted further charting of Bass Strait before sailing west, following the west coast northward, and after another visit to Timor, undertook further exploration along the north coast of Australia. Plagued by contrary winds and ill health,[73] it was decided on 7 July 1803 to return to France. The expedition stopped at Mauritius, where he died of tuberculosis on 16 September 1803. The expedition finally came back to France on 24 March 1804. According to researchers from the University of Adelaide, during this expedition Baudin prepared a report for Napoleon on ways to invade and capture the British colony at Sydney Cove.[74]

The British suspected that the reason for Baudin's expedition was to try to establish a French colony on the coast of New Holland. In response, the

Investigator was declared unseaworthy, so in 1803 Flinders was compelled to return to England as a passenger on Porpoise (1799), together with his charts and logbooks. The vessel stopped in Mauritius, thinking that he would be safe because of the scientific nature of his voyages, though England and France were at war at the time. However, the governor of Mauritius kept Flinders in prison for six and a half years. As a consequence, the first published map of the full outline of Australia was the Freycinet Map of 1811, a product of Baudin's expedition. It preceded the publication of Flinders' map of Australia, Terra Australis or Australia, by three years. Flinders also published in 1814 his account of the voyage in A Voyage to Terra Australis, which was published just before his death at the age of 40.

| When | Who | Ship(s) | Where |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1796 | Matthew Flinders | Tom Thumb | Coastline around Sydney |

| 1798 | Matthew Flinders and George Bass[76] | Norfolk

|

Circumnavigated Tasmania |

| 1801–1802 | Nicolas Baudin, accompanied by Thomas Vasse and numerous naturalists (see below)[77] | Le Géographe and Le Naturaliste

|

The first to explore Western coast; met Flinders at Encounter Bay |

| 1801 | John Murray[78] | Lady Nelson | Bass Strait; discovery of Port Phillip |

| 1802 | Matthew Flinders | Investigator | Circumnavigation of Australia |

| 1817 | Mermaid | Circumnavigation of Australia; charting of the north-western coasts |

See also

- Aboriginal Australians

- Age of Discovery

- Dieppe maps

- European land exploration of Australia

- Indigenous Australians

- Jave la Grande

- History of cartography

- History of geography

- History of Australia

- Terra Australis

- Terra incognita

References

- ISBN 0-285-62303-6)

- ISBN 978-0-9751145-9-9)

- ISBN 0642104816. Archivedfrom the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "A voyage of rediscovery about a voyage of rediscovery". The Guardian. London. 26 March 2007. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ Robert J. King, "The Jagiellonian Globe, a Key to the Puzzle of Jave la Grande", The Globe: Journal of the Australian Map Circle, No. 62, 2009, pp. 1–50.

- ^ Robert J. King, "Regio Patalis: Australia on the map in 1531?", The Portolan, Issue 82, Winter 2011, pp. 8–17.

- ^ Gayle K. Brunelle, "Dieppe School", in David Buisseret (ed.), The Oxford Companion to World Exploration, New York, Oxford University Press, 2007, pp.237–238.

- ^ Inglis, Amirah (1983). "Hargrave, Lawrence (1850–1915)". Lawrence Hargrave. Australian National University (ANU). Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Paulmier de Gonneville Archived 14 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, http://www.bresilbresils.org/decouverte_bresil/index.php?page=relation/palmier Archived 21 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, http://www.passocean.com/HistoiresdeHonfleur/gonneville/gonneville.html Archived 16 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine, http://www.lazareff.com/Le-disque-est-en-crise.html Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, etc. (all in French)

- ^ ISBN 0-528-83015-5.

- ^ "European discovery and the colonisation of Australia - European mariners". Government of Australia. 2015. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ ISBN 0-85558-956-6

- ^ a b Ernest Scott (1928) A Short History of Australia. p. 17. Oxford University Press

- ^ Heeres, J. E. (1899). The Part Borne by the Dutch in the Discovery of Australia 1606–1765, London: Royal Dutch Geographical Society, section III.B

- ^ ISBN 1-875567-36-4.

- ^ Heeres, J. E. (1899). The Part Borne by the Dutch in the Discovery of Australia 1606–1765, London: Royal Dutch Geographical Society, section III. B

- ISBN 0-19-553597-9.

- ISBN 9780642278098. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "Early Knowledge of Australia". Official Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia 1901–1909, No. 3. Melbourne: Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics. 1910. p. 13. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- The Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 26 January 1925. p. 8. Archivedfrom the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ^ "Torres, Luis Vaez de (?–?)". ADBonline.anu.edu.au. ADBonline.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ISBN 0-7022-1275-X

- ^ Phillip E. Playford (2005) "Hartog, Dirk (1580–1621)"[1] Archived 14 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine Australian Dictionary of Biography; Robert J. King, “Dirk Hartog lands on Beach, the Gold-bearing Province”, The Globe, No. 77, 2015, pp.12-52.

- ^ Martin Woods, "For the Dutch Republic, the Great Pacific", National Library of Australia, Mapping our World: Terra Incognita to Australia, Canberra, National Library of Australia, 2013, pp. 111–13.

- ^ Keuning, J. (1950), "Hessel Gerritz", Imago Mundi, vol. VI, pp. 49–67 [58].

- ^ Wieder, F.C. (1942), Tasman's Kaart van Zijn Australische Ontdekkingen 1644 "De Bonaparte-Kaart", Gereproduceerd op de Ware Grootte in Goud en Kleuren naar het Origineel in de Mitchell Library, Sydney (N.S.W.) met Toestemming van de Autoriteiten door F.C. Wieder (in Dutch), The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, p. 12.

- ^ Engelbrecht, W.A. (1945), De Ontdekkingsreis van Jacob le Maire en Willem Cornelisz. Schouten in de Jaren 1615–1617 (in Dutch), The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, p. 152.

- from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Sainsbury, W. Noel, ed. (1884). Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, East Indies, China and Persia, 1625-1629. London: Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts. p. 13.

- ISBN 0-17-001812-1. Archivedfrom the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ J.P.Sigmond and L.H.Zuiderbaan (1976) pp. 54–69.

- ^ Gilsemans, Isaac. "Original chart of the discovery of Tasmania, 24 Nov. to 5 Dec. 1642". National Library of Australla. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. Retrieved 5 April 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Abel Tasman's great voyage". Tai Awatea-Knowledge Net. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ISBN 9780226907338.

- ISBN 9780648043966.

- ^ Van Campen, Jacob (1661), Afbeelding van 't Stadt Huys van Amsterdam [Depiction of the Amsterdam Town Hall] (in Dutch), Amsterdam.

- ^ Victoria: Australian and New Zealand Map Society, pp. 1–14, archivedfrom the original on 11 February 2023, retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ National Library of Australia, Maura O'Connor, Terry Birtles, Martin Woods and John Clark, Australia in Maps: Great Maps in Australia's History from the National Library's Collection, Canberra, National Library of Australia, 2007, p. 32; this map is reproduced in Gunter Schilder, Australia Unveiled, Amsterdam, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1976, p. 402; and in William Eisler and Bernard Smith, Terra Australis: The Furthest Shore, Sydney, International Cultural Corporation of Australis, 1988, pp. 67–84. Image at: home Archived 5 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 0-7270-0800-5

- ISBN 0-7946-0092-1

- ^ Thévenot, Melchisédech (1664), Relations de Divers Voyages Curieux qui n'Ont Point Esté Publiées [Relations of Various Interesting Voyages which Have Not Yet Been Published] (in French), Paris: Thomas Moette.

- ^ Sir Joseph Banks, 'Draft of proposed Introduction to Captn Flinders Voyages', November 1811; State Library of New South Wales, The Papers of Sir Joseph Banks, Series 70.16; quoted in Robert J. King, "Terra Australis, New Holland and New South Wales: the Treaty of Tordesillas and Australia", The Globe, No. 47, 1998, pp. 35–55

- ^ Sir Joseph Banks, 'Draft of proposed Introduction to Captn Flinders Voyages', November 1811; State Library of New South Wales, The Papers of Sir Joseph Banks, Series 70.16; quoted in Robert J. King, "Terra Australis, New Holland and New South Wales: the Treaty of Tordesillas and Australia", The Globe, no. 47, 1998, pp. 35–55, p. 35.

- ^ Cf., e.g., the 1650 globe of Arnold van Langren in Gunter Schilder (1976). Australia Unveiled. Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. pp. 382–383.

- ^ British Library K. Top. cxviii, 19 and Servicio Geográfico del Ejercito, Madrid; O.H.K. Spate, Monopolists and Freebooters, Canberra, Australian National University Press, 1983, pp.279-280.

- ^ J. van Lohuizen (1966) "Houtman, Frederik de (1571?–1627)" [2] Archived 4 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine Australian Dictionary of Biography

- ^ J.P.Sigmond and L.H.Zuiderbaan (1976), pp. 43–50

- ^ J.P.Sigmond and L.H.Zuiderbaan (1976), p. 52

- ^ J. van Lohuizen (1967) "Vlamingh, Willem de (fl. 1697)" [3] Archived 17 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine Australian Dictionary of Biography

- ^ William Dampier (1697) A New Voyage around the World. Reprinted 1937 with an introduction by Sir Albert Gray, President Hakluyt Society. Adam and Charles Black, London. Project Gutenberg [4] Archived 28 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cook, James, Journal of the HMS Endeavour, 1768-1771, National Library of Australia, Manuscripts Collection, MS 1, 22 August 1770

- ISBN 0-522-85093-6

- ISBN 0-522-85214-9. Archivedfrom the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-920843-98-4

- ISBN 1-84383-100-7.

- ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- ^ C.M.H. Clark (1963) A Short History of Australia. pp. 20–21. Signet Classics, A Mentor Book.

- ISBN 0-17-005406-3

- ^ a b David Hill, 1788: The Brutal Truth of the First Fleet

- ^ King, Robert J (December 1999). "What brought Lapérouse to Botany Bay?". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 85, pt.2: 140–147. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ Robert J. King, "What brought Lapérouse to Botany Bay?", Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol.85, pt.2, December 1999, pp.140–147. At: www.articlearchives.com/asia/northern-asia-russia/1659966-1.html ;name=hill

- ^ "Observatory". laperousemuseum.org. 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Christian Services". laperousemuseum.org. 26 April 2013. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Geological Observations". laperousemuseum.org. 16 March 2012. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Garden". laperousemuseum.org. 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Mail". laperousemuseum.org. 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Laperouse's last documents". laperousemuseum.org. 5 July 2012. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Voyage de Dentrecasteaux, envoyé à la recherche de La Pérouse, by Antoine Bruny Dentrecasteaux; M. de Rossel. Published by Imperiale, Paris, 1808.

- ^ Leslie R. Marchant, (1966). "Bruny D'Entrecasteaux, Joseph-Antoine Raymond (1739–1793)." [5] Archived 23 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ^ Dan Sprod (2005) "Furneaux, Tobias (1735–1781)" [6] Archived 24 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine Australian Dictionary of Biography

- ^ Matthew Flinders (1814), A Voyage to Terra Australis; Undertaken for the purpose of completing the discovery of that vast country. G. and W. Nichol, London. Project Gutenberg [7] Archived 6 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Baudin p. 561.

- ^ "Sacre bleu! French invasion plan for Sydney". ABC News. 10 December 2012. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "CORRESPONDENCE". The Advertiser. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 14 October 1901. p. 7. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ K. M. Bowden (1966) "Bass, George (1771–1803)" [8] Archived 12 December 2010 at the Wayback MachineAustralian Dictionary of Biography

- ^ Leslie Marchant, J. H. Reynold.(1966) "Baudin, Nicolas Thomas (1754–1803)" [9] Archived 25 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Australian Dictionary of Biography

- ^ Vivienne Parsons (1967) "Murray, John (1775?–1807?)" [10] Archived 23 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine Australian Dictionary of Biography

- ^ P.Serle (1967) "King, Phillip Parker (1791–1856)" [11] Archived 5 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine Australian Dictionary of Biography