Evolution of fish

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2024) |

The evolution of fish began about 530 million years ago during the

The earliest

During the Devonian period a great increase in fish variety occurred, especially among the ostracoderms and placoderms, and also among the lobe-finned fish and early sharks. This has led to the Devonian being known as the age of fishes. It was from the lobe-finned fish that the tetrapods evolved, the four-limbed vertebrates, represented today by amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds. Transitional tetrapods first appeared during the early Devonian, and by the late Devonian the first tetrapods appeared. The diversity of jawed vertebrates may indicate the evolutionary advantage of a jawed mouth; but it is unclear if the advantage of a hinged jaw is greater biting force, improved respiration, or a combination of factors.

Fish, like many other organisms, have been greatly affected by

Overview

- Fish:

- jawless fish (Agnatha)

- cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes)

- ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii)

- lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii)

- Tetrapods:

Fish may have evolved from an animal similar to a coral-like

Vertebrates, in other words the first fish, originated about 530 million years ago during the Cambrian explosion, which saw the rise in animal diversity.[3]

The first ancestors of fish, or animals that were probably closely related to fish, were

These were followed by indisputable fossil vertebrates in the form of heavily armoured fish discovered in rocks from the

The first

The colonisation of new niches resulted in diversification of body plans and sometimes an increase in size. The Devonian period (395 to 345 Mya) brought in such giants as the placoderm Dunkleosteus, which could grow up to seven meters long, and early air-breathing fish that could remain on land for extended periods. Among this latter group were ancestral amphibians.

The

The later radiations, such as those of fish in the Silurian and Devonian periods, involved fewer taxa, mainly with very similar body plans. The first animals to venture onto dry land were arthropods. Some fish had lungs and strong, bony fins and could crawl onto the land also.

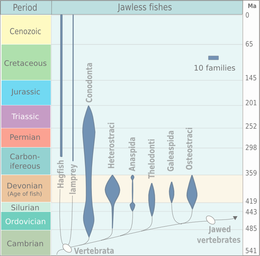

Jawless fish

Jawless fish belong to the

Many

The agnathans as a whole are

The cladogram for jawless fish is based on studies by Philippe Janvier and others for the Tree of Life Web Project.[20] (†=group is extinct)

| Jawless fish |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

†Conodonts

†Ostracoderms

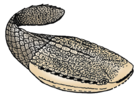

Ostracoderms (lit. 'shell-skinned') are armoured jawless fish of the Paleozoic. The term does not often appear in classifications today because the taxon is paraphyletic or polyphyletic, and has no phylogenetic meaning.[26] However, the term is still used informally to group together the armoured jawless fish.

The ostracoderm armour consisted of 3–5 mm polygonal plates that shielded the head and gills, and then overlapped further down the body like scales. The eyes were particularly shielded. Earlier

The first fossil fish that were discovered were ostracoderms. The Swiss anatomist Louis Agassiz received some fossils of bony armored fish from Scotland in the 1830s. He had a hard time classifying them as they did not resemble any living creature. He compared them at first with extant armored fish such as catfish and sturgeons but later, realizing that they had no movable jaws, classified them in 1844 into a new group "ostracoderms".[27]

Ostracoderms existed in two major groups, the more primitive

Jawed fish

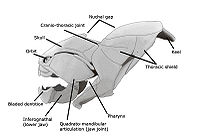

The vertebrate jaw probably originally evolved in the

As in most

It is thought that the original selective advantages offered by the jaw were not related to feeding, but to increases in respiration efficiency. The jaws were used in the

Jawed vertebrates and jawed fish evolved from earlier jawless fish. The cladogram for jawed vertebrates is a continuation of the cladogram in the section above. (†=extinct)

| Jawed vertebrates |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

†Placoderms

Placoderms,

†Spiny sharks

Spiny sharks, class Acanthodii, are extinct fish that share features with both bony and cartilaginous fish, though ultimately more closely related to and ancestral to the latter. Despite being called "spiny sharks", acanthodians predate sharks, though they gave rise to them. They evolved in the sea at the beginning of the Silurian period, some 50 million years before the first sharks appeared. Eventually competition from bony fish proved too much, and the spiny sharks died out in Permian times about 250 Ma. In form they resembled sharks, but their epidermis was covered with tiny rhomboid platelets like the scales of holosteans (gars, bowfins).

Cartilaginous fish

Cartilaginous fish, class

.Bony fish

Bony fish, class Osteichthyes, are characterised by bony skeleton rather than cartilage. They appeared in the late Silurian, about 419 million years ago. The recent discovery of Entelognathus strongly suggests that bony fish (and possibly cartilaginous fish, via acanthodians) evolved from early placoderms.[33] A subclass of the Osteichthyes, the ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii), have become the dominant group of fish in the post-Paleozoic and modern world, with some 30,000 living species. The bony (and cartilaginous) fish groups that emerged after the Devonian were characterised by steady improvements in foraging and locomotion.[34]

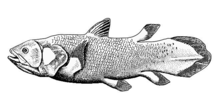

Lobe-finned fish

Lobe-finned fish, fish belonging to the class

Lobe-finned fish, such as

In the Early Devonian (416-397 Mya), the lobe-finned fish split into two main lineages — the

Ray-finned fish

Ray-finned fish, class

Ray-finned fish are a dominant vertebrate group, containing half of all known vertebrate species. They inhabit abyssal depths in the sea, coastal inlets and freshwater rivers and lakes, and are a major source of food for humans.[41]

Timeline

See also

- Comparative anatomy

- Evolution of paired fins

- Ichthyolith

- Convergent evolution in fish

- List of fossil sites

- Lists of prehistoric fish

- List of years in paleontology

- Old Red Sandstone

- Parodies of the ichthys symbol

- Prehistoric life

- Walking fish - fish with tetrapod-like features

- Vertebrate paleontology

References

- ISBN 9781405144490.

- ^ Romer 1970.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-618-00583-3.

- PMID 15941356.

- ^ Lancelet (amphioxus) genome and the origin of vertebrates Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Ars Technica, 19 June 2008.

- S2CID 4402854.

- ^ Waggoner, Ben. "Vertebrates: Fossil Record". UCMP. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ Haines, Tim; Chambers, Paul (2005). The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Firefly Books.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 1954, p. 107.

- ^ a b Berg 2004, p. 599.

- ^ "agnathan". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- PMID 19121930.

- ISBN 978-0-632-05149-6.

- S2CID 84943412. Archived from the originalon 5 January 2013.

- from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- PMID 9866205.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - PMID 11820840.

- ^ Janvier, P. 2010. "MicroRNAs revive old views about jawless vertebrate divergence and evolution." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA) 107:19137-19138. [1] Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine "Although I was among the early supporters of vertebrate paraphyly, I am impressed by the evidence provided by Heimberg et al. and prepared to admit that cyclostomes are, in fact, monophyletic. The consequence is that they may tell us little, if anything, about the dawn of vertebrate evolution, except that the intuitions of 19th century zoologists were correct in assuming that these odd vertebrates (notably, hagfishes) are strongly degenerate and have lost many characters over time."

- ^ a b Benton, M. J. (2005) Vertebrate Palaeontology, Blackwell, 3rd edition, Fig 3.25 on page 73.

- ^ Janvier, Philippe (1997) Vertebrata. Animals with backbones Archived 2013-03-12 at the Wayback Machine. Version 01 January 1997 in The Tree of Life Web Project Archived 2011-05-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ De Renzi M, Budorov K, Sudar M (1996). "The extinction of conodonts-in terms of discrete elements-at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary". Cuadernos de Geología Ibérica. 20: 347–364. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ S2CID 4342260.

- PMID 1598571.

- ISBN 978-0-632-06047-4.

- from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ^ Benton 2005, p. 44.

- ISBN 9780805043662.

- ^ Vertebrate jaw design locked down early Archived 2012-09-08 at the Wayback Machine

- from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ISSN 0031-0239.

- ^ Benton, M. J. (2005) Vertebrate Palaeontology, Blackwell, 3rd edition, Fig 7.13 on page 185.

- S2CID 4462506.

- ^ Helfman et al. 2009, p. 198.

- ^ Allen, G.R., S.H. Midgley, M. Allen. Field Guide to the Freshwater Fishes of Australia. Eds. Jan Knight/Wendy Bulgin. Perth, W.A.: Western Australia Museum, 2002. pp. 54–55.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - PMID 23598338.

- ISBN 9780253356758.

- ^ Nelson 2006.

- PMID 17148426. Archived from the originalon 19 February 2013.

- ^ Forey, Peter L. (1998). History of the Coelacanth Fishes. London: Chapman & Hall.

- ^ a b Introduction to the Actinopterygii Archived 2013-02-17 at the Wayback Machine Museum of Palaeontology, University of California.

Sources

- Benton, Michael J. (2005). Vertebrate Palaeontology.

- Berg, Linda R.; Eldra Pearl Solomon; Diana W. Martin (2004). Biology. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-534-49276-2.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (1954). Encyclopædia Britannica: A new survey of universal knowledge. Vol. 17.

- Helfman, G.; Collette, B.; Facey, D.; Bowen, B. (2009). The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2494-2. Archivedfrom the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- Nelson, Joseph S. (2006). ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- Romer, A.S. (1970). The Vertebrate Body (4 ed.). London: W.B. Saunders.

Further reading

| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Benton MJ (1998) "The quality of the fossil record of the vertebrates" Archived 25 August 2012 at the ISBN 9780471969884.

- Cloutier, R. (2010). "The fossil record of fish ontogenies: Insights into developmental patterns and processes". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 21 (4): 400–413. PMID 19914384.

- Janvier, Philippe (1998) Early Vertebrates, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854047-7

- Long, John A. (1996) The Rise of Fishes: 500 Million Years of Evolution Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5438-5

- McKenzie, D.J.; Farrell, A.P.; and Brauner, C.J. (2011) Fish Physiology: Primitive Fishes Academic Press. ISBN 9780080549521.

- Maisey JG (1996) Fossil Fishes Holt. ISBN 9780805043662.

- Near, T.J.; Dornburg, A.; Eytan, R.I.; Keck, B.P.; Smith, W.L.; Kuhn, K.L.; Moore, J.A.; Price, S.A.; Burbrink, F.T.; Friedman, M. (2013). "Phylogeny and tempo of diversification in the superradiation of spiny-rayed fishes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (31): 12738–12743. PMID 23858462.

- ISBN 9780307277459.

- Introduction to the Vertebrates University of California Museum of Palaeontology.

External links

- Fossil Fish

- Origins of Fish

- Overview of evolution – Carl Sagan

- The Origin of Vertebrates Marc W. Kirschner, iBioSeminars.

- 150 Million Years of Fish Evolution in One Handy Figure ScientificAmerican, 29 August 2013.

- Age Of Fishes Museum Archived 17 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Canowindra - a permanent exhibition some of the best of the thousands of fossils dating from the Devonian Period found nearby.