Extra-illustration

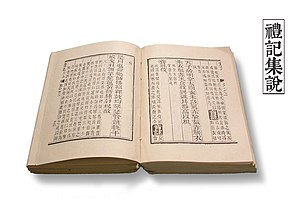

Extra-illustration or grangerisation is the process whereby texts, normally in their published state, are customized by the incorporation of thematically linked prints, watercolors, and other visual materials.[1]

History

Extra-illustration was a vibrant and widespread fashion in Britain and America during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. While there was no set canon of titles chosen for extra-illustration, certain themes and subjects occur repeatedly. From the 1770s to the 1830s, most of the books selected were patriotic in tone and antiquarian or historical in subject. Titles ranged from biography, county histories, and topography to travel, natural history, and Shakespeare. As the pastime became more popular, the genre became more diverse but the scope remained the same: places and people, chronicles of contemporary life, the lives of artistic and theatrical celebrities, and a variety of then-modern writers, notably Byron and Dickens.[2] In 1892 Tredwell published a treatise on the love of book illustrating as a refined pursuit and a signifier of high culture.[3]

Terminology

In Britain, extra-illustration is frequently called grangerising or grangerisation, after James Granger whose seminal book Biographical History of England from Egbert the Great to the Revolution—published in 1769 without illustrations—quickly prompted a fashion for portrait-print collecting and the incorporation of prints and drawings into the printed text. However, the term grangerise only came into use from the 1880s, more than a century after Granger's death.[2] Ironically, for the process of book customization that carries his name, Granger himself never grangerized a book.[4]

Examples

One of the first and certainly the most influential example was made by Richard Bull (MP) who corresponded regularly with James Granger about his print collection and its organisation according to Granger's typologies.[6] The Bull-Granger, as Richard Bull's extra-illustrated copy is often called, is now in the collection of the Huntington Library in California. A large collection of extra-illustrated books was formed during the same period by Anthony Morris Storer who bequeathed them to Eton College in 1799. In the British Museum, a particularly impressive and early example is the copy of Some Account of London by Thomas Pennant, extra-illustrated by John Charles Crowle. Crowle filled fourteen folio volumes, bound in gold-tooled red leather, with a collection of over 3347 prints and drawings of London topography and of portrayals of historical events and people connected with the history of London. It was bequeathed to the British Museum in 1811 where it is registered under number G,1.1.[7]

Perhaps the largest project in the genre are the extra-illustrated books and related materials produced by Alexander Hendras Sutherland and his wife Charlotte, née Hussey, between c.1795 and 1839. The Sutherland collection is now shared between the Ashmolean Museum and the Bodleian Library.[8]

Other examples include an 1868 edition of Aloysius Bertrand's prose-poem collection Gaspard de la Nuit, illustrated with watercolors by Louis Émile Benassit and Lucien Pillot for Henri Breuil, a Dijon chocolatier, now in the collection of the Bibliothèque patrimoniale et d’étude de Dijon,[9] and a copy of the Paul Meurice 1886 French translation of A Midsummer Night's Dream, covered inside and out with watercolors painted by Pinckney Marcius-Simons in 1908, in the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., which has made all the images available online.[5]

References

- Ashmolean. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, 2017. Distributed in the UK by Manchester University Press.

- ^ Tredwell, Daniel M. 1892. A monograph on privately illustrated books: a plea for bibliomania.The New York:De Vinne Press

- ^ Heather Jackson, Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001): pp. 186–87.

- ^ a b "Pinckney Marcius-Simons Illustrations to A Midsummer Night's Dream". collections.folger.edu. June 20, 2022.

- ^ Their letters are preserved at Eton and published entire in Lucy Peltz, "Engraved Portrait Heads and the Rise of Extra-illustration: The Eton Correspondence of the Revd James Granger and Richard Bull, 1769–1774," Walpole Society 66 (2004), pp. 1–161, see http://www.walpolesociety.org.uk/publications/publications.php retrieved 03 January 2016.

- ^ See https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=3316454&partId=1&images=true&museumno=G,1.1&page=1 Retrieved 03 January 2016.

- ^ "Sutherland Collection". sutherland.ashmolean.museum. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ ""Gaspard de la Nuit" illustré par Emile Benassit et Lucien Pillot". monamilouisbertrand.blogspot.com. August 23, 2011.

Further reading

- Jackson, Holbrook (1932). "Part XXVIII. Of grangeritis" in The Anatomy of Bibliomania, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Peltz, Lucy (2017). Facing the Text: Extra-Illustration, Print Culture, and Society in Britain 1769–1840, Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, 2017. ISBN 978-0-87328-261-1.

- Shaddy, Robert A. (2000). "Grangerizing," The Book Collector 49 no.4 (winter): 535–546.

External links

Media related to Extra-illustration at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Extra-illustration at Wikimedia Commons