Facial trauma

| Facial trauma | |

|---|---|

| |

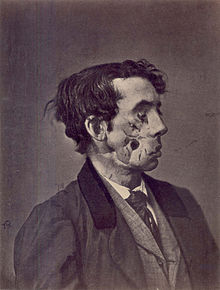

| 1865 illustration of a private injured in the American Civil War by a shell two years previously | |

| Specialty | Oral and maxillofacial surgery |

Facial trauma, also called maxillofacial trauma, is any

Facial injuries have the potential to cause disfigurement and loss of function; for example, blindness or difficulty moving the jaw can result. Although it is seldom life-threatening, facial trauma can also be deadly, because it can cause severe bleeding or interference with the

In developed countries, the leading cause of facial trauma used to be

Signs and symptoms

Cause

Injury mechanisms such as falls, assaults,

Diagnosis

Classification

|

|

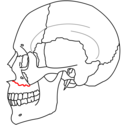

| Le Fort I fractures | |

|

|

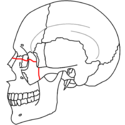

| Le Fort II fractures | |

|

|

| Le Fort III fractures | |

Soft tissue injuries include

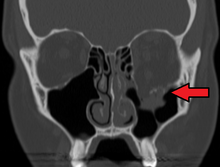

Commonly injured facial bones include the

At the beginning of the 20th century,

Prevention

Measures to reduce facial trauma include laws enforcing seat belt use and public education to increase awareness about the importance of seat belts[8] and motorcycle helmets.[9] Efforts to reduce drunk driving are other preventative measures; changes to laws and their enforcement have been proposed, as well as changes to societal attitudes toward the activity.[8] Information obtained from biomechanics studies can be used to design automobiles with a view toward preventing facial injuries.[7] While seat belts reduce the number and severity of facial injuries that occur in crashes,[8] airbags alone are not very effective at preventing the injuries.[3] In sports, safety devices including helmets have been found to reduce the risk of severe facial injury.[19] Additional attachments such as face guards may be added to sports helmets to prevent orofacial injury (injury to the mouth or face);[19] mouth guards also used. In addition to factors listed above, correction of dental features that are associated with receiving more dental trauma also helps, such as increased overjet, Class II malocclusions, or correction of detofacal deformities with small mandible [20][21]

Treatment

An immediate need in treatment is to ensure that the airway is open and not threatened (for example by tissues or foreign objects), because

A

Treatment aims to repair the face's natural bony architecture and to leave as little apparent trace of the injury as possible.[1] Fractures may be repaired with metal plates and screws commonly made from Titanium.[1] Resorbable materials are also available; these are biologically degraded and removed over time but there is no evidence supporting their use over conventional Titanium plates.[24] Fractures may also be wired into place. Bone grafting is another option to repair the bone's architecture, to fill out missing sections, and to provide structural support.[1] Medical literature suggests that early repair of facial injuries, within hours or days, results in better outcomes for function and appearance.[12]

Surgical specialists who commonly treat specific aspects of facial trauma are oral and maxillofacial surgeons, otolaryngologists, and plastic surgeons.[4] These surgeons are trained in the comprehensive management of trauma to the lower, middle and upper face and have to take written and oral board examinations covering the management of facial injuries.

Prognosis and complications

By itself, facial trauma rarely presents a threat to life; however it is often associated with dangerous injuries, and life-threatening complications such as blockage of the airway may occur.[4] The airway can be blocked due to bleeding, swelling of surrounding tissues, or damage to structures.[25] Burns to the face can cause swelling of tissues and thereby lead to airway blockage.[25] Broken bones such as combinations of nasal, maxillary, and mandibular fractures can interfere with the airway.[1] Blood from the face or mouth, if swallowed, can cause vomiting, which can itself present a threat to the airway because it has the potential to be aspirated.[26] Since airway problems can occur late after the initial injury, it is necessary for healthcare providers to monitor the airway regularly.[26]

Even when facial injuries are not life-threatening, they have the potential to cause disfigurement and disability, with long-term physical and emotional results.[7] Facial injuries can cause problems with eye, nose, or jaw function[1] and can threaten eyesight.[12] As early as 400 BC,

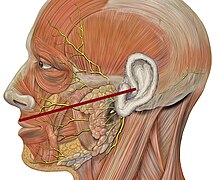

Incising wounds of the face may involve the parotid duct. This is more likely if the wound crosses a line drawn between the tragus of the ear to the upper lip. The approximate location of the course of the duct is the middle third of this line.[28]

Nerves and muscles may be trapped by broken bones; in these cases the bones need to be put back into their proper places quickly.

Infection is another potential complication, for example when debris is ground into an abrasion and remains there.[4] Injuries resulting from bites carry a high infection risk.[3]

Epidemiology

As many as 50–70% of people who survive traffic accidents have facial trauma.

Facial fractures are distributed in a fairly

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Seyfer AE, Hansen JE (2003). pp. 423–24.

- ^ ISBN 0-07-135294-5.

- ^ ISBN 0-7817-5561-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Neuman MI, Eriksson E (2006). pp. 1475–77.

- ^ a b Kellman RM. Commentary on Seyfer AE, Hansen JE (2003). p. 442.

- S2CID 231900892.

- ^ ISBN 0-387-98820-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-11-06. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ PMID 11382418.

- ^ PMID 16270942.

- ^ a b c d e

Hunt JP, Weintraub SL, Wang YZ, Buechter KJ (2003). "Kinematics of trauma". In Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL (eds.). Trauma. Fifth Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 149. ISBN 0-07-137069-2.

- ^ a b Jeroukhimov I, Cockburn M, Cohn S (2004). pp.10–11.

- ^ PMID 18178381.

- ^ a b Neuman MI, Eriksson E (2006). pp. 1480–81.

- ^ "Le Fort I fracture" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d e Shah AR, Valvassori GE, Roure RM (2006). "Le Fort Fractures". EMedicine. Archived from the original on 2008-10-20.

- ^ "Le Fort II fracture" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary.

- ^ "Le Fort III fracture" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary.

- ^ "Le Fort fracture" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary.

- ^ from the original on 2007-10-09.

- PMID 21880516.

- PMID 20831636.

- ^ a b Jeroukhimov I, Cockburn M, Cohn S (2004). pp.2–3.

- PMID 18262768.

- |intentional=yes}}.)

- ^ a b

Parks SN (2003). "Initial assessment". In Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL (eds.). Trauma. Fifth Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 162. ISBN 0-07-137069-2.

- ^ PMID 18207702.

- PMID 16023907.

- (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ^ Seyfer AE, Hansen JE (2003). p. 434.

- ^ Seyfer AE, Hansen JE (2003). p. 437.

- ^ Neuman MI, Eriksson E (2006). p. 1475. "The age distribution of facial fractures follows a relatively normal curve, with a peak incidence between 20 and 40 years of age."

- ^ Jeroukhimov I, Cockburn M, Cohn S (2004). p. 11. "The incidence of brain injury in patients with maxillofacial trauma varies from 15 to 48%. The risk of serious brain injury is particularly high with upper facial injury."

Cited texts

- Jeroukhimov I, Cockburn M, Cohn S (2004). "Facial trauma: Overview of trauma care". In Thaller SR (ed.). Facial trauma. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-4625-2. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- Neuman MI, Eriksson E (2006). "Facial trauma". In Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM (eds.). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-5074-1. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- Seyfer AE, Hansen JE (2003). "Facial trauma". In Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL (eds.). Trauma. Fifth Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 423–24. ISBN 0-07-137069-2.

Further reading

- The Gillies Archives at Queen Mary's Hospital, Sidcup - Documents and images from the early days of reconstructive surgery for severe facial trauma experienced by soldiers in World War I.