Fairey III

| Fairey III | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fairey IIIF on HMS Furious | |

| Role | reconnaissance aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Fairey Aviation

|

| First flight | 14 September 1917 |

| Introduction | 1918 |

| Retired | 1942 |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force Fleet Air Arm |

| Number built | 964 |

| Variants | Fairey Gordon Fairey Seal |

The

Design and development

The prototype of the Fairey III was the N.10

Following tests both as a floatplane and with a conventional wheeled undercarriage, production orders were placed for two versions both powered by the Maori, the IIIA and IIIB, with 50 and 60 aircraft planned, respectively. The Fairey IIIA was a reconnaissance aircraft intended to operate from aircraft carriers, and as such was fitted with a wheeled or skid undercarriage, while the IIIB was intended as a floatplane bomber, with larger span (increased from 46 ft 2 in/14.19 m to 62 ft 9 in/19.13 m) upper wings and a bombload of three 230 lb (105 kg) bombs.[2] While all 50 IIIAs were built, only 28 of the IIIBs were completed as intended, as a new improved bomber/reconnaissance floatplane, the Fairey IIIC was available, of which 36 were produced, which reverted to short equal-span wings like the IIIA but was powered by the much more powerful and reliable 375 hp (280 kW) Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engine and could still carry a useful bombload. Many of the IIIBs were completed as IIICs.[3]

The first major production model was the IIID, which was an improved IIIC, with provision for a third crewmember and capable of being fitted with either a floatplane or a conventional wheeled undercarriage.

A Fairey III floatplane (G-EALQ) with a 450 hp Napier Lion was entered into the Air Ministry Commercial Amphibian Competition of September 1920.[6]

The most prolific and enduring of the Fairey IIIs was the final model, the IIIF, which was designed to meet

Over 350 IIIFs were operated by the Fleet Air Arm, making it the most widely used type of aircraft in Fleet Air Arm service between the wars[9] and also the second most produced British military aircraft of the inter-war years behind the Hawker Hart family.[10]

Three IIIFs were modified as a radio-controlled gunnery

Operational history

Early versions

The IIIA and IIIB saw limited service towards the end of the war, with some IIIBs being used for

IIID

The IIID was operated by the Royal Air Force and Fleet Air Arm as well as the Naval Aviation of Portugal (11 aircraft) and the air forces of Australia.

Australia received six IIIDs, the first being delivered in August 1921. In 1924, the third of the Australian IIIDs, designated ANA.3 (or Australian Naval Aircraft No. 3), flown by Stanley Goble (later Air Vice Marshal) and Ivor McIntyre was awarded the Britannia Trophy by the Royal Aero Club for circumnavigating Australia in 44 days. The IIID remained in Australian service until 1928.[13]

Portugal ordered its first IIIDs in 1921. Its first aircraft, modified as the F.400 and named "Lusitânia", was used for an attempt to fly across the South Atlantic and demonstrate the new aerial navigation system devised by

The IIID entered Fleet Air Arm Service in 1924, operating from shore bases, aircraft carriers and floats until replaced by the IIIF in 1930. The RAF Cape Flight used four IIIDs to carry out a long distance formation flight from Cairo to Cape Town and back in 1926, the first long range formation flight by the RAF and the first RAF flight to South Africa.[15] Fleet Air Arm IIIDs were used to defend British interests in Shanghai against rebel Chinese forces in 1927.[16]

IIIF

The IIIF entered service with the RAF in

In the Fleet Air Arm, the IIIF replaced the IIID as a spotter-reconnaissance aircraft, operating on floats from the Royal Navy's cruisers and battleships, and with wheels, from the aircraft carriers HMS Furious, Eagle, Courageous, Glorious and Hermes.[21]

The IIIF remained in front line service well into the 1930s, with the last front line RAF squadron, 202 Squadron, re-equipping with Supermarine Scapas in August 1935,[22] and the final front line Fleet Air Arm squadron, 822 Squadron retained the IIIF until 1936.[23] The IIIF remained in use in second line roles, and despite being declared obsolete in 1940,[24] some were still in use as target tugs as late as 1941.[25]

Civil use

The first prototype III was purchased back by Fairey in 1919, fitted with new, single bay wings and a Napier Lion engine and entered into the 1919 Schneider Trophy race, on 10 September. The race was abandoned due to fog, however.[26]

Four IIICs were civilianized, some with an extra cockpit between the two standard ones and sometimes with an enlarged rear cockpit. One carried five passengers, one in the extra cockpit and four in the rear.

A small number of civil operated IIIDs and IIIFs were used for survey duties in the 1920s and 30s, while in October 1934 a single IIIF was entered into the MacRobertson Air Race, reaching the finishing line in Melbourne but too late to be classed as completing the race.[29]

Variants

- Fairey N.10

- The first Fairey III prototype.

- Fairey IIIA

- Two-seat reconnaissance biplane, powered by a 260 hp (190 kW) Sunbeam Maori IIV-12 piston engine; 50 built.

- Fairey IIIB

- Three-seat patrol, bomber seaplane, powered by a Sunbeam Maori IIV-12 piston engine, it had the same fuselage as the IIIA but the fin, wing and rudder had a larger area, it also had larger floats then the IIIA; 30 built.

- Fairey IIIC

- Two-seat reconnaissance, bomber and general-purpose seaplane, powered by a 375 hp (280 kW) Rolls-Royce Eagle V-12 piston engine; 36 built.[30]

- Fairey IIID

- Two-seat general-purpose biplane, powered by a 375 hp (280 kW) Rolls-Royce Eagle V-12 or 450 hp (336 kW) Napier Lion W-12 piston engine; 227 built.[31]

- Fairey IIIE

- Designation sometimes used for Fairey Ferret radial-engine reconnaissance and general purpose aircraft. Three built.[32]

- Fairey IIIF

- Two-seat general-purpose biplane or three-seat spotter-reconnaissance biplane, powered by a Napier Lion W-12 piston engine.

- Fairey IIIF Mk.I

- First production version of the Fairey IIIF. Three-seat spotter-reconnaissance biplane, powered by a Napier Lion VA W-12 piston engine, of composite wood and metal construction. 55 built.[33]

- Fairey IIIF Mk.II

- Three-seat spotter-reconnaissance biplane, powered by a Napier Lion XIA W-12 piston engine, of composite wood and metal construction; 33 built.[33]

- Fairey IIIF Mk.III

- Three-seat spotter-reconnaissance biplane, powered by a Napier Lion XIA piston engine, with a fabric-covered all-metal structure; 291 built.[33]

- Fairey IIIF Mk.IV

- Two-seat general purpose biplane for the Napier Lion XIA W-12 piston engine; 243 built.[33]

- Fairey IIIF Mk.V

- The original designation of the Gordon.

- Fairey IIIF Mk.VI

- Original designation of the Seal.

- Queen IIIF

- Radio-controlled gunnery training aircraft; Three built.

- Fairey IIIM

- Civil version; three built.

- Fairey F.400

- The first IIID (manufacturers serial number F.400) for the Portuguese Navy was delivered as a special long-range variant with an extended wing-span of 61 feet. It was also referred to as the Fairey Transatlantic and given the name Luzitania when it was used for an attempt to fly across the South Atlantic in 1922, stopping at Saint Peter and Paul Rocks.[14]

Operators

- Royal Australian Air Force - IIID (Six originally ordered by the Royal Australian Navy but transferred to the newly formed air force)

- Argentine Naval Aviation - Purchased six IIIF MkIIIM (Special) powered by 450 hp (336 kW) Lorraine Dietrich Ed12 engine in 1928. They entered service in 1929. The remaining aircraft were re-engined with Armstrong Siddeley Panthers in 1935, with the last aircraft being retired in 1942.[34]

- Royal Canadian Air Force - One Fairey IIIC aircraft, one IIIF aircraft

- Chilean Air Force - IIIF

- Chilean Navy - IIIF

- Egypt bought a single IIIF in 1939.[35]

- Irish Air Corps - purchased a single IIIF MkII in 1928, being destroyed in a crash in 1934.[35]

- Royal New Zealand Air Force - New Zealand purchased two IIIF MkIIIMs in 1928, adding another in 1933, with one remaining in use in 1940.[35]

- Soviet Air Force- One Fairey IIIF aircraft, used for tests and trials.

- Royal Swedish Navy- IIID

- Royal Air Force - IIIA, IIIB, IIIC, IIIF[36]

- Fleet Air Arm - IIID, IIIF[24]

Surviving aircraft

A single example of the Fairey III is preserved in Portugal's

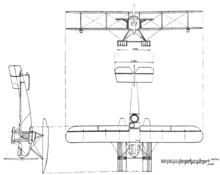

Specifications (Fairey IIIF Mk.IV)

Data from Fairey Aircraft since 1915 [38]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2-3

- Length: 34 ft 4 in (10.46 m) [39]

- Wingspan: 45 ft 9 in (13.94 m) [39]

- Height: 12 ft 5 in (3.78 m) [39]

- Wing area: 439 sq ft (40.8 m2)

- Empty weight: 3,855 lb (1,749 kg) [40]

- Gross weight: 6,041 lb (2,740 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Napier Lion XIW-12 water-cooled piston engine, 570 hp (430 kW)

- Propellers: 2-bladed fixed-pitch propeller

Performance

- Maximum speed: 120 mph (190 km/h, 100 kn) at 10,000 ft (3,000 m)

- Range: 1,520 mi (2,450 km, 1,320 nmi) maximum fuel, no bombs

- Service ceiling: 20,000 ft (6,100 m)

- Rate of climb: 833 ft/min (4.23 m/s)

- Wing loading: 13.8 lb/sq ft (67 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 0.094 hp/lb (0.155 kW/kg)

Armament

- Guns:

- 1 × forward firing .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers machine gun

- 1 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis Gunin flexible mount for observer

- Bombs:

- Up to 500 lb (227 kg) bombs can be carried under wings

See also

Related development

References

- ^ Taylor 1988, p.71.

- ^ Mason 1994, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Mason 1994, p.90.

- ^ Mason 1994, p.131.

- ^ a b c Taylor 1988, p.96.

- ^ "The Air Ministry Seaplane (Amphibian) Competition". Flight, Vol. XII, No. 682, 23 September 1920, p. 1013.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p.145.

- ^ Jarrett March 1994, pp.60–61.

- ^ Thetford May 1994, p.33.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p.78.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p.86.

- ^ Isaacs 1984, pp.40–49.

- ^ a b Taylor 1988, pp.98–100.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p.102–103.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p.147.

- ^ Mason 1994, p.178.

- ^ Thetford 1994, p.33.

- ^ Thetford 1994, pp.34–35.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p.148.

- ^ Thetford 1994, p.202.

- ^ Mason 1994, p.128.

- ^ Taylor 1988, pp.72–74.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p.89

- ^ Taylor 1988, pp.87–89

- ^ Jackson 1973, pp.200–203.

- ^ "The New Fairey Long Distance Seaplane" Flight, 19 January 1922, pp. 35-36

- ^ Taylor 1988, p.94.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p.129.

- ^ a b c d Taylor 1988, p.165.

- ^ Jarrett Aeroplane November 2011, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b c d Jarrett Aeroplane November 2011, p. 85.

- ^ Halley 1980, p. 352.

- ^ Thetford 1994, p. 38.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p.166.

- ^ a b c Air Publication 1351 Volume 1 The III.F. (G.P.) Aeroplane

- ^ Mason 1994, p.179.

Bibliography

- Grant, James Ritchie. "Anti-Clockwise: Australia the Wrong Way". Air Enthusiast, No. 82, July–August 1999, pp. 60–63. ISSN 0143-5450

- Halley, James J. The Squadrons of the Royal Air Force. Tonbridge, UK: Air Britain (Historians), 1980. ISBN 0-85130-083-9.

- Isaacs, Keith. "The Fairey IIID In Australia". ISSN 0143-5450.

- Jackson, A.J. British Civil Aircraft since 1919: Volume 2. London:Putnam, 1973. ISBN 0-370-10010-7.

- Jarrett, Philip. "Database: Fairey IIIF". Aeroplane, November 2011, Vol 39 No 11 Issue 463. London: Kelsey Publishing Group. pp. 69–85. ISSN 0143-7240.

- Jarrett, Philip. "Fairey IIIF: Part 1". Aeroplane Monthly, March 1994, Vol 22 No 3 Issue 251. London:IPC. pp. 58–63. ISSN 0143-7240.

- Jarrett, Philip. "Fairey IIIF: Part 2". Aeroplane Monthly, April 1994, Vol 22 No 4 Issue 252. London:IPC. pp. 50–55. ISSN 0143-7240.

- Lezon, Ricardo Martin & Stitt, Robert M. (January–February 2004). "Eyes of the Fleet: Seaplanes in Argentine Navy Service, Part 2". Air Enthusiast. No. 109. pp. 46–59. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Mason, Francis K. The British Bomber since 1914. London:Putnam, 1994. ISBN 0-85177-861-5.

- Nuñez Padin, Jorge Felix (July 1998). "Les Fairey IIIF de l'aviation navale argentin" [The Fairey IIIFs of Argentinian Naval Aviation]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French). No. 64. pp. 17–19. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Taylor, H.A. Fairey Aircraft since 1915. London:Putnam, 1988. ISBN 0-370-00065-X.

- Thetford, Owen. British Naval Aircraft since 1912. London:Putnam, Fourth edition 1978. ISBN 0-370-30021-1.

- Thetford, Owen. "Fairey IIIF and Gordon in Service: Part 1". Aeroplane Monthly, May 1994, Vol 22 No 5 Issue 253. London:IPC. pp. 32–38. ISSN 0143-7240.

- Vevis, Gérassimos & Karatzas, Alexandre (June 1999). "Les Hydravions Fairey IIIF grecs" [Greek Fairey IIIF Seaplanes]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French). No. 75. pp. 46–52. ISSN 1243-8650.