Fantasia 2000

| Fantasia 2000 | |

|---|---|

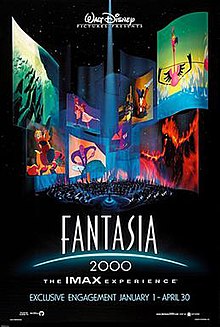

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Tim Suhrstedt |

| Edited by |

|

Production company | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 74 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $80–85 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $90.9 million[2] |

Fantasia 2000 is a 1999 American animated musical anthology film produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation and released by Walt Disney Pictures. Produced by Roy E. Disney and Donald W. Ernst, it is the sequel to Disney's 1940 animated feature film Fantasia. Like its predecessor, Fantasia 2000 consists of animated segments set to pieces of classical music. Segments are introduced by celebrities including Steve Martin, Itzhak Perlman, Quincy Jones, Bette Midler, James Earl Jones, Penn & Teller, James Levine, and Angela Lansbury in live action scenes directed by Don Hahn.

After numerous unsuccessful attempts to develop a Fantasia sequel, The Walt Disney Company revived the idea shortly after Michael Eisner became chief executive officer in 1984. Development paused until the commercial success of the 1991 home video release of Fantasia convinced Eisner that there was enough public interest and funds for a sequel, to which he assigned Disney as executive producer. The music for six of the film's eight segments is performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by James Levine. The film includes The Sorcerer's Apprentice from the 1940 original. Each new segment was produced by combining traditional animation with computer-generated imagery. Fantasia 2000 is also generally linked to the Disney Renaissance, as it commemorates to Walt Disney's third animated feature film.[4][5]

Fantasia 2000 premiered on December 17, 1999, at Carnegie Hall in New York City as part of a concert tour that also visited London, Paris, Tokyo, and Pasadena, California. The film was then released in 75 IMAX theaters worldwide from January 1 to April 30, 2000, marking the first major Hollywood motion picture to be released in IMAX and also the first feature-length animated film to be released in the format. Its general release in regular theaters followed on June 16, 2000. The film received mostly positive reviews from critics, who praised several of its sequences, while also deeming its overall quality uneven in comparison to its predecessor. Budgeted at about $80–$85 million, the film grossed $90.9 million worldwide.

Program

- Symphony No. 5 by Ludwig van Beethoven. The film begins with the sound of an orchestra tuning and Deems Taylor's introduction from Fantasia. Panels showing various segments from Fantasia fly in outer space and form the set and stage for an orchestra. Musicians take their seats and tune up as animators and artists draw at their desks before James Levine approaches the conductor's podium and signals the beginning of the piece. In the segment proper, abstract patterns and shapes that resemble hundreds of colorful triangle-shaped butterflies in dozens of magentas, reds, oranges, yellows, greens, cyans, turquoises, blues, indigos, violets, purples, pinks, grays, whites, and browns in various shades, tints, tones, and hues explore a world of light and darkness whilst being pursued by a swarm of dark black pentagon or hexagon-shaped bats. The world is ultimately conquered by light and color.

- Pines of Rome by Ottorino Respighi. A family of humpback whales are able to fly. The calf is separated from his parents, and becomes trapped in an iceberg. Eventually, he finds his way out with his mother's help. The family join a larger pod of whales, who fly and frolic through the clouds to emerge into outer space. Introduced by Steve Martin, who gives a brief history on Fantasia's original purpose, after which Itzhak Perlman introduces the segment proper.

- Rhapsody in Blue by George Gershwin. Set in New York City in the 1930s, and designed in the style of Al Hirschfeld's known caricatures of the time, the story follows four individuals who wish for a better life. Duke is a construction worker who dreams of becoming a jazz drummer; Joe is a down-on-his-luck unemployed man who wishes he could get a job; Rachel is a little girl who wants to spend time with her busy parents instead of being shuttled around by her governess; and John is a harried rich husband who longs for a simpler, more fun life. The segment ends with all four getting their wish, though their stories interact with each other's without any of them knowing.[6] Introduced by Quincy Jones with pianist Ralph Grierson.

- Piano Concerto No. 2, Allegro, Opus 102 by Dmitri Shostakovich. Based on the fairy tale "The Steadfast Tin Soldier" by Hans Christian Andersen, a broken toy soldier with one leg falls in love with a toy ballerina and protects her from an evil jack-in-the-box.[7] Unlike the original story, this version has a happy ending. Introduced by Bette Midler featuring pianist Yefim Bronfman.

- The Carnival of the Animals (Le Carnival des Animaux), Finale by Camille Saint-Saëns. A flock of flamingoes tries to force a slapstick member, who enjoys playing with a yo-yo, to engage in the flock's "dull" routines. Introduced by James Earl Jones with animator Eric Goldberg.

- sorcerer Yen Sid who attempts some of his master's magic tricks before knowing how to control them. Introduced by Penn & Teller rather than using an archived recording of Deems Taylor introducing the segment as in the original film. The scene where Mickey shakes hands with Levine's predecessor Leopold Stokowski is like that in the original film but Mickey is now voiced by Wayne Allwine instead of Walt Disney. This outro leads directly to the intro for Pomp and Circumstance, with Donald Duck and Daisy Duck voiced by Tony Anselmo and Russi Taylor, respectively.

- Pomp and Circumstance – Marches 1, 2, 3 and 4 (also known as Land of Hope and Glory) by Sir Edward Elgar. Based on the story of Noah's Ark from the Book of Genesis, Donald Duck is Noah's assistant and Daisy Duck is Donald's girlfriend. Donald is given the task of gathering the animals to the Ark, and misses, loses, and reunites with Daisy in the process. Introduced by James Levine.

- Firebird Suite—1919 Version by Igor Stravinsky. A Sprite is awoken by her companion, an elk, and accidentally wakes a fiery spirit of destruction in a nearby volcano who destroys the forest and seemingly the Sprite. The Sprite survives and the elk encourages her to restore the forest to its normal state. Introduced by Angela Lansbury.

Production

Development

Fantasia is timeless. It may run 10, 20 or 30 years. It may run after I'm gone. Fantasia is an idea in itself. I can never build another Fantasia. I can improve. I can elaborate. That's all.

—Walt Disney[8]

In 1940, Walt Disney released Fantasia, his third animated feature film, consisting of eight animated segments set to pieces of classical music. Initially he planned to have the film on continual release with new segments replacing older ones so audiences would never see the same film twice. The idea was dropped following the film's initial low box office receipts and a mixed response from critics. Following preliminary work on new segments, the idea was shelved by 1942 and was not revisited for the remainder of Disney's life. In 1980, animators Wolfgang Reitherman and Mel Shaw started preliminary work on Musicana, a feature film "mixing jazz, classical music, myths, modern art ... following the old Fantasia format" that was to present "ethnic tales from around the world with the music of the various countries".[9] The project was cancelled in favor of Mickey's Christmas Carol (1983).[10]

The idea of a Fantasia sequel was revived shortly after

During the search for a suitable conductor, Disney and Walt Disney Feature Animation president Thomas Schumacher invited Metropolitan Opera conductor James Levine and manager Peter Gelb to a meeting in September 1991.[21] Disney recalled: "I asked James what his thought was on a three minute version of Beethoven's fifth symphony. He paused and went 'I think the right three minutes would be beautiful'".[22] In November 1992, Disney, Schumacher, Levine, Gelb, and Butoy met in Vienna to discuss a collection of story reels developed, one of them being Pines of Rome, which Levine took an immediate liking to. Butoy described Levine's enthusiasm toward the film as "like a kid in a candy store".[22] Because Katzenberg continued to express some hostility towards the film, Disney held development meetings without him and reported directly to Eisner instead, something that author James B. Stewart wrote "would have been unthinkable on any other future animation project."[14]

Production began under the working title of Fantasia Continued with a release in 1997.[11] The title was changed to Fantasia 1999, followed by Fantasia 2000 to coincide with its theatrical release in 2000. Disney formed its initial running order with half of the Fantasia program and only "three or four new numbers"[23] with the aim of releasing a "semi-new movie".[24] Realizing the idea would not work, he kept three Fantasia segments—The Sorcerer's Apprentice, The Nutcracker Suite, and Dance of the Hours—in the program for "quite a while".[25] Night on Bald Mountain was the most difficult segment for him to remove from his original running order because it was one of his favorites. He had placed it in the middle of the film without Ave Maria, but felt it did not work and scrapped the idea.[26] Later on, Dance of the Hours was dropped and The Nutcracker Suite was replaced by Rhapsody in Blue during the last few months of production following the response from numerous test screenings.[27] Disney kept The Sorcerer's Apprentice in the final program as a homage to Fantasia.[28] The segment underwent digital restoration by Cinesite in Los Angeles.[29] Disney considered using Clair de Lune, a piece originally made for Fantasia that followed two Great white herons flying through the Everglades at night, but thought it was "pretty boring".[27] An idea to have "a nightmare and a dream struggling for a sleeping child's soul" to Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini by Sergei Rachmaninoff was fully storyboarded, but fell through.[3]

Segments

Symphony No. 5

Symphony No. 5 is an abstract segment created by Pixote Hunt with story development by Kelvin Yasuda. In December 1997, after rejecting pitches from four other animators, Disney and Ernst asked Hunt for his ideas.[30] Hunt first thought of the story on a morning walk in Pasadena, California, one depicting a battle of "good" against "evil" and how the conflict resolves itself.[31] It took Hunt approximately two years, from start to finish, to complete the segment. Disney and Ernst decided to go with Hunt's idea; Hunt avoided producing an entirely abstract work because "you can get something abstract on every computer screen" with ease.[32] Hunt divided the segment into 31 mini-scenes, noting down points in which he would employ vivid color when the music was bright and fluid, and then switch to darker hues when the music felt darker and denser.[33] To gain inspiration in how the shapes would move, Hunt and his associates visited San Diego Zoo, a butterfly farm, and observed slow motion footage of bats.[34] The segment combines hand drawn backgrounds using pastels and paint that were scanned into the Computer Animation Production System (CAPS), and computer-generated imagery (CGI) of abstract shapes and effects, which were layered on top.[35] Hunt explained that scanning each drawing "was a one-shot deal" as the platen that pressed onto it would alter the pastel once it had been scanned.[36] At one point during production, Hunt and Yasuda completed 68 pastel drawings in eight days.[33] The segment was produced using Houdini animation software.[29]

Pines of Rome

Pines of Rome was the first piece Disney suggested for the film, as well as the first to be animated; designs appeared in the studio's dailies as early as October 1993.[37] Butoy served as director with James Fujii handling the story.[20] The opening to the piece gave Disney the idea of "something flying".[38] Butoy sketched the sequence on yellow Post-it notes.[39] The story originally involved the whales flying around from the perspective of a group of penguins, but the idea was scrapped to make the baby whale a central character. The whales were also set to return to Earth but Butoy said it "never felt quite right", leading to the decision to have them break through a cloud ceiling and enter a different world by the supernova.[40] Butoy created a "musical intensity chart" for the animators to follow which "tracked the ups and downs of the music ... as the music brightens so does the color", and vice versa.[41] He explained that because CGI was in its infancy during development, the first third of the segment was hand drawn using pencil to get a feel of how the whales would move. When the drawings were scanned into the CAPS system, Butoy found the whales were either moving too fast or had less weight to them. The drawings were altered to make the whales slow down and "more believable".[42] The eyes of the whales were drawn by hand, as the desired looks and glances were not fully achievable using CGI.[43] Butoy recalled the challenge of having the water appear and move as naturally as possible; the team decided to write computer code from scratch as traditional animation would have been too time-consuming and would have produced undesired results.[44] The code handling the pod of whales was written so the whales would move away if they were to collide and not bump into, overlap, or go through each other. The same technique was used for the stampede scene in The Lion King (1994), which was produced at the same time.[45]

Rhapsody in Blue

Rhapsody in Blue is the first Fantasia segment with music from the American composer. It originated in 1995 when director and animator Eric Goldberg approached Al Hirschfeld about the idea of an animated short set to Gershwin's composition in the style of Hirschfeld's illustrations. In December 1998, the Goldbergs pitched Rhapsody in Blue to Thomas Schumacher and received the green-light to produce it, and Hirschfeld agreed to serve as artistic consultant and allowed the animators to adapt his works.[46] Duke is named after jazz musician Duke Ellington.[47] The bottom of his toothpaste tube reads "NINA", an Easter egg referencing Hirschfeld's daughter Nina, whose name Hirschfeld inscribed in several of his drawings since her birth in 1945. Another easter egg references artist Emily Jiuliano, whose name is shown as "E. Jiuliano".[48] Rachel was designed after the Goldbergs' daughter;[49] John, or "Flying John", is based on animation historian and author John Culhane and Hirschfeld's caricature of Alexander Woollcott.[49][50][51] Goldberg took Hirschfeld's original illustration of Gershwin and animated it to make him play part of the "rhapsody" on the piano.[49] The most difficult part of this particular scene to animate was the turning of Gershwin's head, as the original drawing depicted one angle of his head. The illustration also featured Ira Gershwin alongside his brother George, but Ira is not shown in the scene nor anywhere else in the film. Featured in the crowd emerging from the hotel are depictions of Brooks Atkinson and Hirschfeld, along with his wife Dolly Haas.[52][49] The sequence was so chromatically complex that the rendering process using the CAPS system delayed work on Tarzan.[29]

Piano Concerto No. 2

Piano Concerto No. 2 was directed by Butoy with art director Michael Humphries. It originated in the 1930s when Walt Disney wished to adapt a collection of Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales into an animated film. The artists completed a series of preliminary designs based on the stories, including ones for "The Steadfast Tin Soldier" from 1938 by Bianca Majolie[53] that were stored in the studio's animation research library and used for a 1991 Disney book that retold the story accompanied with the storyboard sketches. When Disney suggested using the Shostakovich piece, Butoy flipped through the book and found the story's structure fit to the music.[54] When Humphries saw the sketches he designed the segment with works by Caravaggio and Rembrandt in mind to give the segment a "timeless" feel, while keeping the colors "as romantic as possible" during the scenes when the soldier and ballerina are first getting acquainted.[55][56] Live action footage of a real ballerina was used as a guide for the toy ballerina's movements.[57] Butoy found the Jack-in-a-box a difficult character to design and animate with its spring base and how he moved with the box. His appearance went through numerous changes, partly due to the lack of reference material available to the team.[58]

The segment marked the first time the Disney studio created a film's main characters entirely from CGI;

The Carnival of the Animals, Finale

The Carnival of the Animals, Finale was directed and animated by Goldberg; his wife Susan was its art director. The idea originated from animator Joe Grant, one of the two story directors on Fantasia who loved the ostriches in Dance of the Hours. When development for Fantasia 2000 began, Grant suggested the idea of having one of the ostriches play with a yo-yo to the last movement of The Carnival of the Animals. The ostriches were later changed to flamingos as Disney wished to avoid reintroducing characters from the original film and thought flamingos would look more colorful on the screen.[62] Goldberg was partly inspired by co-director Mike Gabriel, who would play with a yo-yo as he took a break from working on Pocahontas (1995); Gabriel is given a credit for "yo-yo tricks" in the end credits.[63] The segment was produced with CGI and 6,000 watercolor paintings on heavy bond paper.[64] Susan chose a distinct colour palette for the segment which she compared to the style of a Hawaiian shirt. The Goldbergs and their team visited the zoo in Los Angeles and San Diego to study the anatomy and movement of flamingos.[65]

The Sorcerer's Apprentice

Pomp and Circumstance (Land of Hope and Glory)

Mostly known as Britain's most loved patriotic song (thanks its choral counterpart

The Firebird

To close the film, Disney wanted a piece that was "emotionally equivalent" to the Night on Bald Mountain and Ave Maria segments that closed Fantasia.[72] Disney chose The Firebird as the piece to use after "half a dozen" others were scrapped, including Symphony No. 9 by Beethoven and the "Hallelujah Chorus" from Messiah by Handel.[24] Disney thought of the idea of the Earth's destruction and renewal after passing Mount St. Helens following its eruption in 1980.[73] French twins Paul and Gaëtan Brizzi from Disney's Paris studio were hired to direct the segment.[29] The Sprite is a Dryad-like creature from Greek mythology.[74] Her form changes six times; she is introduced as a Water Sprite who plants flowers as a Flower Sprite. She becomes a Neutral Sprite where her growth trail stops and an Ash Sprite when the forest has been destroyed. The segment ends with her as a Rain-Wave Sprite, followed by the Grass Sprite. The segment originally ended with the Sprite in the form of a flowing river that rises up into the sky and transforms into a Sun Sprite, but this was abandoned.[75] The elk's antlers were produced by CGI and placed on top of its body that was drawn traditionally. The segment was produced using Houdini animation software.[29]

Music

The music to The Sorcerer's Apprentice was already recorded on January 9, 1938 for the first film at Culver Studios, California with Leopold Stokowski conducting a group of session musicians. The recording of Rhapsody in Blue used in the film is an edited version of Ferde Grofé's orchestration of the piece performed by the Philharmonia Orchestra with conductor Bruce Broughton. The shortened version was made by cutting 125 bars of piano solo in three different places.[76] A recording of James Levine conducting both pieces with the Philharmonia appears on the film's soundtrack.[77]

The remaining six pieces were recorded at the Medinah Temple in Chicago, performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Levine.[78] Pines of Rome was re-arranged in 1993 by Bruce Coughlin, who reduced the four-movement piece by cutting the second movement and trimming sections of the third and fourth movements. The piece was recorded on March 28, 1994.[79] The second recording involved Symphony No. 5, Carnival of the Animals, and Pomp and Circumstance, on April 25, 1994.[79] Carnival of the Animals, Finale uses two pianos played by Gail Niwa and Philip Sabransky. Pomp and Circumstance was arranged by Peter Schickele[80] and features the Chicago Symphony Chorus and soprano soloist Kathleen Battle. The next recording took place on April 24, 1995 for Piano Concerto No. 2 with pianist Yefim Bronfman.[79] On September 28, 1996, The Firebird was the final piece to be recorded; its session lasted for three hours.[79] The piece was arranged using four sections from Stravinsky's 1919 revision of the score.

Interstitials

Disney felt the need to keep

Hahn recalled some difficulty in finding someone to host the film, so the studio decided to use a group of artists and musicians from various fields of entertainment.

Release

Fantasia 2000 was officially announced on February 9, 1999 during a Disney presentation at the

Home media

Fantasia 2000 was first released on VHS and DVD on November 14, 2000,[98][99] with both featuring a specially made introduction in which Roy gives a history of key innovations brought by various Disney productions (specifically Steamboat Willie, Flowers and Trees, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Fantasia, The Great Mouse Detective, Beauty and the Beast, Toy Story 2 and Dinosaur). While it was available as a single-disc DVD, a three-disc set titled The Fantasia Anthology was released, including a digital copy of the film, a restored print of Fantasia to commemorate its 60th anniversary, and a third disc containing bonus features.[100]

On November 30, 2010, the film was issued for DVD and Blu-ray in a single and two-disc set with Fantasia and a four-disc DVD and Blu-ray combo pack. The Blu-ray transfer presents the film in 1080p high-definition video with DTS-HD Master Audio 7.1 surround sound.[101] The film was withdrawn from release after its return to the "Disney Vault" moratorium on April 30, 2011.[102]

The film, along with Fantasia and the 2018 compilation Celebrating Mickey (containing 13 Mickey Mouse shorts from Steamboat Willie to Get a Horse!), was reissued in 2021 as part of the U.S. Disney Movie Club exclusive The Best of Mickey Collection (Blu-ray/DVD/Digital).[103] Both films were also broadly released for the first time in 2021 on multiple U.S. purchased streaming platforms, including Movies Anywhere and its retailers.[104][105]

Soundtrack

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Symphony No. 5" | 2:51 |

| 2. | "Pines of Rome" | 10:18 |

| 3. | "Rhapsody in Blue" | 12:32 |

| 4. | "Piano Concerto No. 2, Allegro, Opus 102" | 7:22 |

| 5. | "Carnival of the Animals (Le Carnaval des Animaux), Finale" | 1:54 |

| 6. | "The Sorcerer's Apprentice" | 9:33 |

| 7. | "Pomp and Circumstance, Marches #1, 2, 3, & 4" | 6:18 |

| 8. | "Firebird Suite—1919 Version" | 9:11 |

Reception

Box office

Fantasia 2000 first opened in IMAX theatres for a four-month run from January 1 to April 30, 2000, becoming the first animated feature-length film shown in the format.[92][109] The idea to release it in IMAX first originated from Dick Cook during meetings the studio had about the best way to create "a sense of event" for the film. Roy Disney believed its uniqueness from typical feature films gave it a psychological advantage.[110][111] A temporary 622-seat theatre costing almost $4 million was built in four weeks for its Los Angeles run as Disney was unable to reach an agreement to only have the film shown during the four months at the city's sole IMAX theater at the time at the California Science Center.[64][112] Disney enforced the exclusive screening rule on the other IMAX cinemas that showed the film which limited its release.[113] Each theater was decorated with a museum-like exhibit with educational material and large displays.[114]

After opening at 75 theaters worldwide, the film grossed over $2.2 million in 54 cinemas in North America in its opening weekend, averaging $41,481 per theater,[115] and $842,000 from 21 screens in 14 markets.[116] It set new records for the highest gross for any IMAX engagement and surpassed the highest weekly total for any previously released IMAX film.[117] Its three-day worldwide gross surpassed $3.8 million, setting further records at 18 venues worldwide.[118] Fantasia 2000 grossed a worldwide total of $21.1 million in 30 days,[119] and $64.5 million at the end of its IMAX run.[120]

Following its release in 1,313 regular theatres in the United States on June 16, 2000, the film grossed an additional $2.8 million in its opening weekend that ranked eleventh at the box office. This followed nearly half a year of release in the IMAX format, possibly blunting the amount earned in the weekends of wide release.[121] Fantasia 2000 has earned a total worldwide gross of over $90.8 million since its release, with $60.7 million of that total from the U.S. market, and the rest through foreign box office sales.[2] The film had cost around $90 million and was viewed by Eisner as Roy Disney's "folly".[97]

Critical response

On

Entertainment Weekly gave a "B−" rating; its reviewer, Bruce Fretts, called Symphony No. 5 "maddeningly abstract", Piano Concerto No. 2 "charmingly traditional" and thought Rhapsody in Blue fit well to the music, but Pomp and Circumstance "inexplicably inspires biblical kitsch". The review ends with a criticism of the inadequate quality of The Sorcerer's Apprentice on the IMAX screen.[124] Todd McCarthy of Variety pointed out that while the original Fantasia felt too long and formal, its "enjoyable follow-up is, at 75 minutes, simply too breezy and lightweight". He summarized the film "like a light buffet of tasty morsels rather than a full and satisfying meal".[125]

In his December 1999 review for the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert gave the film a rating of three stars out of four. He described some of the animation (such as Firebird Suite, his favorite segment) as "powerful", though he thought others, like the dance of the abstract triangles in Symphony No. 5, to be "a little pedestrian". He admired Rhapsody in Blue and its interlocking stories, pointing out its style was reminiscent of the Madeline picture books by Ludwig Bemelmans. He thought Pines of Rome presented itself well in the IMAX format and found the Piano Concerto No. 2 played "wonderfully as a self-contained film", while he found The Sorcerer's Apprentice to be "not as visually sharp as the rest of the film". He nonetheless described the film overall as "splendid entertainment".[7] Film critic Stephen Holden of The New York Times wrote that the film "often has the feel of a giant corporate promotion whose stars are there simply to hawk the company's wares" while noting the film "is not especially innovative in its look or subject matter."[97] Firebird Suite was his favorite segment which left "a lasting impression of the beauty, terror, and unpredictability of the natural world". He found The Sorcerer's Apprentice fit well with the rest of the film and the battle in Symphony No. 5 too abbreviated to amount to much.[6] He found the segment with the whales failed in that the images "quickly become redundant".[6] He found Rhapsody in Blue to be the second-best in the film with its witty, hyper-kinetic evocation of the melting pot with sharply defined characters. He found the segment with the flamingos cute and the one with the tin soldier to be romantic.[6] James Berardinelli found the film to be of uneven quality. He felt Symphony No. 5 was "dull and uninspired", the yo-yoing flamingos "wasteful", and the New York City-based story of Rhapsody in Blue interesting but out of place in this particular movie. He found the story of the tin soldier to successfully mix its music with "top-notch animation" and "an emotionally rewarding story". He felt the Firebird section was "visually ingenious", and Pomp and Circumstance the most light-hearted episode and the one with the most appeal to children, in an otherwise adult-oriented film. To him The Sorcerer's Apprentice was an enduring classic.[74]

David Parkinson of British film magazine

Accolades

| Award | Category | Name | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

28th Annie Awards[128] |

Outstanding Achievement in An Animated Theatrical Feature | Walt Disney Pictures | Nominated |

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Character Animation | Eric Goldberg | Won | |

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Production Design In an Animated Feature Production | Susan McKinsey Goldberg | Won | |

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Production Design In an Animated Feature Production | Gaetan Brizzi and Carl Jones |

Nominated | |

| Individual Achievement in Storyboarding | Ted C. Kierscey | Won | |

| 43rd Grammy Awards[129] | Compilation Soundtrack Album for a Motion Picture, Television or other Visual Media | James Levine and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra | Nominated |

| 12th PGA Golden Laurel Awards[citation needed] | Vision Award for Theatrical Motion Pictures | Won | |

| 1st Phoenix Film Critics Society Awards[130] | Best Animated Film | Nominated | |

| Best Family Film | Nominated |

Credits

Note: All segments performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra with conductor James Levine, except where noted.

| Segment | Personnel |

|---|---|

| Live-action scenes |

|

| Symphony No. 5 in C minor, I. Allegro con brio |

|

| Pines of Rome |

|

| Rhapsody in Blue |

|

| Piano Concerto No. 2 in F Major, Allegro, Op. 102 |

|

| The Carnival of the Animals (Le Carnival des Animaux), Finale |

|

| The Sorcerer's Apprentice |

|

| Pomp and Circumstance – Marches 1, 2, 3 and 4 |

|

| Firebird Suite – 1919 Version |

|

Short films and cancelled sequel

Development on a third film began in 2002 under the working title Fantasia 2006. Plans were made to include One by One by Pixote Hunt and The Little Matchgirl by Roger Allers in the film before the project was cancelled in 2004 for unknown reasons, with the proposed segments instead being released as standalone short films.

Destino is an animated short film released in 2003 by The Walt Disney Company. Destino is unique in that its production began in 1945, 58 years before its eventual completion. The project was originally a collaboration between Walt Disney and Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, and features music written by Mexican songwriter Armando Domínguez and performed by Dora Luz. In 1999, Walt Disney's nephew, Roy E. Disney, while working on Fantasia 2000, unearthed the dormant project and decided to bring it back to life. It was later released as a bonus short on the special edition DVD and Blu-ray of Fantasia 2000.

Lorenzo is a 2004 American animated short film produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation about a cat named Lorenzo who is "dismayed to discover that his tail has developed a personality of its own". The short was directed by Mike Gabriel and produced by Baker Bloodworth. It premiered at the Florida Film Festival on March 6, 2004 and later appeared as a feature before the film Raising Helen; however, it did not appear on the DVD release of the film. Work on the film began in 1943, but was shelved. It was later found along with Destino.

One by One is a traditionally animated short film directed by Pixote Hunt and released by Walt Disney Pictures on August 31, 2004, as an extra feature on the DVD release of The Lion King II: Simba's Pride Special Edition.

The Little Matchgirl is a 2006 animated short film directed by Roger Allers and produced by Don Hahn. It is based on an original story by Hans Christian Andersen entitled The Little Girl with the Matches or The Little Match Girl, published in 1845.[131]

References

- ^ a b c d "Fantasia/2000 (2000)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Fantasia 2000 (35mm & IMAX)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ a b c Corliss, Richard (December 5, 1999). "Disney's Fantastic Voyage". Time. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ Josh Spiegel (February 13, 2014). "'Fantasia 2000,' and Why It Should Be Considered Part of the Disney Renaissance". PopOptiq.

- ^ "'Fantasia 2000' And The Final Gasps Of The Disney Renaissance". /Film. October 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Holden 2001, pp. 212–213.

- ^ a b "Fantasia/2000". RogerEbert.com. December 31, 1999. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ Solomon, Charles (August 26, 1990). "Fantastic 'Fantasia'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ Warga, Wayne (October 26, 1980). "Disney Films: Chasing the Changing Times". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Solomon 1995

- ^ a b Taylor, Cathy (October 22, 1994). "Disney Waves Magic Wand And Sequel Comes To Life After 54 Years". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Brennan, Judy (August 19, 1997). "Coming, Sooner or Later". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Stewart 2006, p. 106.

- ^ Previn 1991

- ^ Stewart 2006, p. 288.

- ^ "Fantasia (Re-issue) (1990)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Christiansen, Richard (October 31, 1991). "'Fantasia' A Hit With Video Audience". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ a b Culhane 1999, p. 11.

- ^ a b Culhane 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 8.

- ^ a b Culhane 1999, p. 176.

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 30:42–30:53

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (December 29, 1999). "Walt's nephew leads new Disney 'Fantasia'". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 30:55–31:05

- ^ Archive.org.

- ^ a b Kaufman, J.B. (October 1999). "A New Life for Fantasia". Animation World Magazine, Issue 4.7. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 32:35–32:49

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Robertson, Barbara (January 2000). "Fantasia 2000". Computer Graphics World. 23. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Culhane 1999, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Supplemental Features: Symphony No. 5: Creating Symphony No. 5 at 00:32–00:44

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 24.

- ^ a b Culhane 1999, p. 29.

- ^ Supplemental Features: Symphony No. 5: Creating Symphony No. 5 at 01:14–01:24

- ^ Supplemental Features: Symphony No. 5: Creating Symphony No. 5 at xx:xx–xx:xx

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 35.

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 13.

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 39.

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 45.

- ^ Supplemental Features: Creating Pines of Rome at 2:52–3:49

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 9:51–10:17

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 10:32–11:59

- ^ Supplemental Features: Creating Pines of Rome at 2:30–2:51

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 12:27–13:30

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 14:56–15:19

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 58.

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 17:52–17:59

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 17:59–18:36

- ^ a b c d Solomon, Charles (December 1999). "Rhapsody in Blue: Fantasia 2000's Jewel in the Crown". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (August 4, 2015). "Disney Animation Historian John Culhane Dies". Animation Magazine. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 25:08–25:39

- ^ Supplemental Features: Rhapsody in Blue: Inspirations from Hirschfeld

- ^ Supplemental Features: 1938 Storyboards by Bianca Majolie

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 24:54–26:27

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 31:46–31:55

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 30:32–31:07

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 31:13–31:27

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 32:29–32:51

- ^ Supplemental Features: Creating Piano Concerto No. 2 at 00:06–00:30

- ^ Supplemental Features: Creating Piano Concerto No. 2 at 02:57–03:38

- ^ Supplemental Features: Creating Piano Concerto No. 2 at 03:48–04:27

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 28:28–29:24

- ^ Supplemental Features: Creating "Carnival of the Animals (Le Carnival des Animaux) Finale at xx:xx–xx:xx

- ^ a b Noxon, Christopher (December 30, 1999). "The 'Sorcerer's' Apprentices". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- Archive.org.

- ^ "Wonko's World: BBC survey on English national anthem". blog.wonkosworld.co.uk. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 32:50–33:06

- ^ Stewart 2006, p. 289.

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 33:33–33:48

- ^ Supplemental Features: Pomp and Circumstance: Creating Pomp and Circumstance at xx:xx–xx:xx

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 00:55–01:19

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 36:27–36:43

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 36:44–37:18

- ^ a b Berardinelli 2005, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Supplemental Features: Firebird Suite–1919 Version: Character Designs: Sprite

- ^ Banagale 2014, p. 153.

- ^ a b "Fantasia 2000". Soundtrack.net. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at xx:xx–xx:xx

- ^ a b c d Culhane 1999, p. 177.

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 35:27–35:54

- ^ Bonus Material: The Making of Fantasia 2000 at 39:15–39:42

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 15.

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 14.

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 5:08–5:22

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 29:38–29:50

- ^ Supplemental Features: The Interstitials: Creating the Interstitials at 02:19–03:36

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 17.

- ^ Culhane 1999, p. 16.

- ^ Segment Directors Audio Commentary at 16:06–16:24

- ^ Frankel, Daniel (February 10, 1999). "Disney's "Fantasia 2000" going Imax". E! Online. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ Roman, Monica (February 9, 1999). "Disney, Imax set 'Fantasia 2000'". Variety. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Matthews, Jack (December 16, 1999). "'Fantasia 2000' grows to IMAX height". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ Liberman, Paul (December 20, 1999). "Disney Unwraps 'Fantasia' Sequel, After a Long Spell". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- ^ Cowan, Rob (December 23, 1999). "Return of the Sorcerer's Apprentice". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ^ Disney Magazine, Fall 1999 Collector's Issue.

- ^ Dutka, Elaine (January 3, 2000). "'Fantasia/2000' New Year's Eve Gala Draws an Artistic Crowd". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c Stewart 2006, p. 346–347.

- The Free Library.

- ^ "Billboard". Nielsen Business Media, Inc. September 16, 2000. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved October 24, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Perigard, Mark (November 12, 2000). "ON DVD; Disc additions enhance 'Fantasia' celebration". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ^ "Fantasia & Fantasia 2000: 2-Movie Collection Special Edition". Ultimate Disney/DVDizzy. September 1, 2010. Archived from the original on March 20, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Fantasia/Fantasia 2000 2 Movie Collection Special Edition". Disney DVD. Archived from the original on March 12, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ "The Best of Mickey Collection Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Fantasia". Movies Anywhere. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Fantasia 2000". Movies Anywhere. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Bramburger, Bradley (January 8, 2000). "Classical: Keeping Score". Billboard. p. 33. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ^ "Top Classical Albums". Billboard. July 8, 2000. p. 37. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ^ "Child's Play: 'Thomas' Film Soundtrack on Track". Billboard. July 15, 2000. p. 71. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ISBN 9780810882027. Archivedfrom the original on March 17, 2022. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Noxon, Christopher (December 7, 1999). "L.A. Imax Says No, So Disney Builds Its Own Huge Screen". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ "News Beat – 'Fantasia' B.O. fantastic". New York Daily News. January 5, 2000. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office". Box Office Mojo. January 3, 2000. Archived from the original on August 4, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ "'Fantasia/2000' smashes house records at IMAX theaters worldwide in its opening weekend". Business Wire. January 3, 2000. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ "'Fantasia/2000' orchestrates nearly $4 million in just three days at 75 IMAX theaters worldwide". Business Wire. January 4, 2000. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ "Fantasia/2000 soars past the $21 million mark in just one month of release at 75 venues worldwide". Business Wire. January 30, 2000. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ Watson, Pernell (May 26, 2000). "Fantasia/2000' coming to regular theater soon". Daily Press. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ^ Natale, Richard (June 19, 2000). "Audiences Dig 'Shaft,' but June Business Isn't Right On". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ^ "Fantasia 2000 (1999)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- CBS Interactive. Archivedfrom the original on November 24, 2018. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ Fretts, Bruce (January 14, 2000). "Fantasia 2000". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ McCarthy, Bruce (December 22, 1999). "Review: 'Fantasia 2000'". Variety. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ Parkinson, David. "Fantasia 2000". Empire. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ Sibley, Brian (June 2000). "Fantasia 2000". BFI: Sight & Sound. Archived from the original on August 3, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ "Legacy: 28th Annual Annie Award Nominees and Winners (2000)". International Animated Film Society. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ "And the nominees are..." Ocala Star-Banner. p. 5D. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ "Past Years Awards". Phoenix Film Critics Society. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ^ "Disney Animation Archive: Deleted Movies/Fantasia 2006/Notes/index.php". Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

Bibliography

- Banagale, Ryan (2014). Arranging Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue and the Creation of an American Icon. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-997840-3.

- ISBN 978-1-932112-40-5. Archivedfrom the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Culhane, John (1999). Fantasia 2000: Visions of Hope. Disney Editions. ISBN 0-7868-6198-3.

- ISBN 978-0-385-41341-1.

- Holden, Stephen (2001). The New York Times Film Reviews 1999–2000. ISBN 978-0-415-93696-5. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Solomon, Charles (1995). Disney That Never Was: The Stories and Art of Five Decades of Unproduced Animation. Hyperion. ISBN 978-0-7868-6037-1.

- ISBN 978-0-7434-9600-1.

DVD media

- UPC 786936163872.

- Various segment directors (November 14, 2000). The Fantasia Anthology: Fantasia 2000—Audio Commentary (Segment Directors) (DVD). Disc 2 of 3. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. UPC 786936163872.

- Various cast and crew members (November 14, 2000). The Fantasia Anthology: Fantasia 2000—The Making of Fantasia 2000 (DVD). Disc 2 of 3. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. UPC 786936163872.

- Various cast and crew members (November 14, 2000). The Fantasia Legacy—Supplemental Features (DVD). Disc 3 of 3. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. UPC 786936163872.

External links

- Official website

- Fantasia 2000 at IMDb

- Fantasia 2000 at the TCM Movie Database

- Fantasia 2000 at AllMovie

- Fantasia 2000 at Box Office Mojo