Fantasy literature

| Fantasy |

|---|

| Media |

|

| Genre studies |

|

| Subgenres |

|

| Fandom |

| Categories |

|

| Speculative fiction |

|---|

|

|

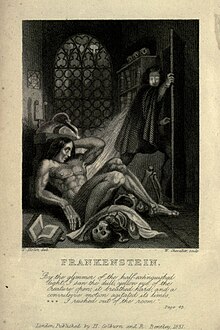

Fantasy literature is

Fantasy is considered a genre of speculative fiction and is distinguished from the genres of science fiction and horror by the absence of scientific or macabre themes, respectively, though these may overlap. Historically, most works of fantasy were in written form, but since the 1960s, a growing segment of the fantasy genre has taken the form of films, television programs, graphic novels, video games, music and art.

Many fantasy novels originally written for children and adolescents also attract an adult audience. Examples include Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, the Harry Potter series, The Chronicles of Narnia, and The Hobbit.

History

Beginnings

Stories involving magic and terrible monsters have existed in spoken forms before the advent of printed literature. Classical mythology is replete with fantastical stories and characters, the best known (and perhaps the most relevant to modern fantasy) being the works of Homer (Greek) and Virgil (Roman).[1]

The philosophy of Plato has had great influence on the fantasy genre. In the Christian Platonic tradition, the reality of other worlds, and an overarching structure of great metaphysical and moral importance, has lent substance to the fantasy worlds of modern works.[2]

With Empedocles (c. 490 – c. 430 BC), elements they are often used in fantasy works as personifications of the forces of nature.[3]

It was influential in Europe and the Middle East. It used various animal fables and magical tales to illustrate the central Indian principles of political science. Talking animals endowed with human qualities have now become a staple of modern fantasy.[6]

The

The

Celtic folklore and legend has been an inspiration for many fantasy works.[12]

The Welsh tradition has been particularly influential, owing to its connection to King Arthur and its collection in a single work, the epic Mabinogion.[12] One influential retelling of this was the fantasy work of Evangeline Walton.[13] The Irish Ulster Cycle and Fenian Cycle have also been plentifully mined for fantasy.[12] Its greatest influence was, however, indirect. Celtic folklore and mythology provided a major source for the Arthurian cycle of chivalric romance: the Matter of Britain. Although the subject matter was heavily reworked by the authors, these romances developed marvels until they became independent of the original folklore and fictional, an important stage in the development of fantasy.[14]

From the 13th century

Romance or chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that reworked legends, fairy tales, and history to suit the readers' and hearers' tastes, but by c. 1600 they were out of fashion, and Miguel de Cervantes famously burlesqued them in his novel Don Quixote. Still, the modern image of "medieval" is more influenced by the romance than by any other medieval genre, and the word medieval evokes knights, distressed damsels, dragons, and other romantic tropes.[15]

Renaissance

At the time of the

During the Renaissance, Giovanni Francesco Straparola wrote and published The Facetious Nights of Straparola (1550–1555), a collection of stories of which many are literary fairy tales. Giambattista Basile wrote and published the Pentamerone, which was the first collection of stories to contain solely what would later be known as fairy tales. The two works include the oldest recorded form of many well-known (and some more obscure) European fairy tales.[19] This was the beginning of a tradition that would both influence the fantasy genre and be incorporated in it, as many works of fairytale fantasy appear to this day.[20]

In a work on

Enlightenment

Literary fairy tales, such as those written by Charles Perrault (1628–1703) and Madame d'Aulnoy (c.1650 – 1705), became very popular early in the Age of Enlightenment. Many of Perrault's tales became fairy tale staples and were influential to later fantasy. When d'Aulnoy termed her works contes de fée (fairy tales), she invented the term that is now generally used for the genre, thus distinguishing such tales from those involving no marvels.[23] This approach influenced later writers who took up the folk fairy tales in the same manner during the Romantic era.[24]

Several fantasies aimed at an adult readership were also published in 18th century France, including Voltaire's "contes philosophique" The Princess of Babylon (1768) and The White Bull (1774).[25] This era, however, was notably hostile to fantasy. Writers of the new types of fiction such as Defoe, Richardson, and Fielding were realistic in style, and many early realistic works were critical of fantastical elements in fiction.[26]

However, in the Elizabethan era in England, fantasy literature became extraordinarily popular and fueled populist and anti-authoritarian sentiment during the 1590s.[27] Topics that were written about included "fairylands in which the sexes traded places [and] men and immortals mingl[ing]".[27]

Romanticism

The Romantics invoked the medieval romance as a model for the works they wanted to produce, in contrast to the realism of the Enlightenment.

In the later part of the Romantic period, folklorists collected folktales, epic poems, and ballads, and released them in printed form. The

The Romantic interest in medievalism also resulted in a revival of interest in the literary fairy tale. The tradition begun with Giovanni Francesco Straparola and Giambattista Basile and developed by Charles Perrault and the French précieuses was taken up by the German Romantic movement. The German author Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué created medieval-set stories such as Undine (1811) and Sintram and his Companions (1815), which would later inspire British writers such as George MacDonald and William Morris.[32][33][34]

In France, the main writers of Romantic-era fantasy were Charles Nodier with Smarra (1821) and Trilby (1822)[37][38] and Théophile Gautier who penned such stories as "Omphale" (1834) and "One of Cleopatra's Nights" (1838) as well as the novel Spirite (1866).[39][40]

Victorian era

Fantasy literature was popular in

The history of modern fantasy literature began with George MacDonald, author of such novels as The Princess and the Goblin (1868) and Phantastes (1868), the latter of which is widely considered to be the first fantasy novel written for adults. MacDonald also wrote one of the first critical essays about the fantasy genre, "The Fantastic Imagination", in his book A Dish of Orts (1893).[42][43] MacDonald was a major influence on both Tolkien and C. S. Lewis.[44]

The other major fantasy author of this era was William Morris, an admirer of the Middle Ages and a poet who wrote several fantastic romances and novels in the latter part of the 19th century, including The Well at the World's End (1896). Morris was inspired by the medieval sagas, and his writing was deliberately archaic in the style of the chivalric romances.[45] Morris's work represented an important milestone in the history of fantasy, as while other writers wrote of foreign lands or of dream worlds, Morris was the first to set his stories in an entirely invented world.[46]

Authors such as

Several classic

At this time, the terminology for the genre was not settled. Many fantasies in this era were termed fairy tales, including Max Beerbohm's "The Happy Hypocrite" (1896) and MacDonald's Phantastes.[53] It was not until 1923 that the term "fantasist" was used to describe a writer (in this case, Oscar Wilde) who wrote fantasy fiction.[54] The name "fantasy" was not developed until later; as late as J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit (1937), the term "fairy tale" was still being used.

After 1901

An important factor in the development of the fantasy genre was the arrival of magazines devoted to fantasy fiction. The first such publication was the German magazine Der Orchideengarten which ran from 1919 to 1921.[55] In 1923, the first English-language fantasy fiction magazine, Weird Tales, was created.[56] Many other similar magazines eventually followed.[57] and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction[58]

H. P. Lovecraft was deeply influenced by Edgar Allan Poe and to a somewhat lesser extent, by Lord Dunsany; with his Cthulhu Mythos stories, he became one of the most influential writers of fantasy and horror in the 20th century.[59]

Despite MacDonald's future influence, and Morris' popularity at the time, it was not until around the start of the 20th century that fantasy fiction began to reach a large audience, with authors such as Lord Dunsany (1878–1957) who, following Morris's example, wrote fantasy novels, but also in the short story form.[45] He was particularly noted for his vivid and evocative style.[45] His style greatly influenced many writers, not always happily; Ursula K. Le Guin, in her essay on style in fantasy "From Elfland to Poughkeepsie", wryly referred to Lord Dunsany as the "First Terrible Fate that Awaiteth Unwary Beginners in Fantasy", alluding to young writers attempting to write in Lord Dunsany's style.[60] According to S. T. Joshi, "Dunsany's work had the effect of segregating fantasy—a mode whereby the author creates his own realm of pure imagination—from supernatural horror. From the foundations he established came the later work of E. R. Eddison, Mervyn Peake, and J. R. R. Tolkien.[61]

In Britain in the aftermath of World War I, a notably large number of fantasy books aimed at an adult readership were published, including Living Alone (1919) by Stella Benson,[62] A Voyage to Arcturus (1920) by David Lindsay,[63] Lady into Fox (1922) by David Garnett,[62] Lud-in-the-Mist (1926) by Hope Mirrlees,[62][64] and Lolly Willowes (1926) by Sylvia Townsend Warner.[62][65] E. R. Eddison was another influential writer who wrote during this era. He drew inspiration from Northern sagas, as Morris did, but his prose style was modeled more on Tudor and Elizabethan English, and his stories were filled with vigorous characters in glorious adventures.[46] Eddison's most famous work is The Worm Ouroboros (1922), a long heroic fantasy set on an imaginary version of the planet Mercury.[66]

Literary critics of the era began to take an interest in "fantasy" as a genre of writing, and also to argue that it was a genre worthy of serious consideration. Herbert Read devoted a chapter of his book English Prose Style (1928) to discussing "Fantasy" as an aspect of literature, arguing it was unjustly considered suitable only for children: "The Western World does not seem to have conceived the necessity of Fairy Tales for Grown-Ups".[43]

In 1938, with the publication of

The first major contribution to the genre after World War II was

The tradition established by these predecessors of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has continued to thrive and be adapted by new authors. The

It is not uncommon for fantasy novels to be ranked on The New York Times Best Seller list, and some have been at number one on the list, including most recently, Brandon Sanderson in 2014,[71] Neil Gaiman in 2013,[72] Patrick Rothfuss[73] and George R. R. Martin in 2011,[74] and Terry Goodkind in 2006.[75]

Style

Symbolism often plays a significant role in fantasy literature, often through the use of archetypal figures inspired by earlier texts or folklore. Some argue that fantasy literature and its archetypes fulfill a function for individuals and society and the messages are continually updated for current societies.[76]

Michael Moorcock observed that many writers use archaic language for its sonority and to lend color to a lifeless story.[31] Brian Peters writes that in various forms of fairytale fantasy, even the villain's language might be inappropriate if vulgar.[79]

See also

- Children's literature

- Fantastique

- List of fantasy novels

- Mythology

Footnotes

- ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ISBN 0-253-17461-9.

- ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ Jacobs 1888, Introduction, page xv; Ryder 1925, Translator's introduction, quoting Hertel: "the original work was composed in Kashmir, about 200 B.C. At this date, however, many of the individual stories were already ancient."

- ^ Doris Lessing, Problems, Myths and Stories Archived 2016-05-09 at the Wayback Machine, London: Institute for Cultural Research Monograph Series No. 36, 1999, p 13

- ISBN 0-415-93890-2.

- ^ Isabel Burton, Preface Archived 21 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, in Richard Francis Burton (1870), Vikram and The Vampire.

- ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ISBN 1-932265-07-4

- ISBN 0-268-00790-X

- ISBN 0-521-47735-2.

- ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ISBN 0-8057-0950-9, p38

- ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- ISBN 0-19-512199-6

- ISBN 0-521-47735-2

- ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- ISBN 0-8108-6829-6

- ^ Lin Carter, ed. Realms of Wizardry p xiii–xiv Doubleday and Company Garden City, NY, 1976

- ^ ISBN 978-0-563-48714-2.

- ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ISBN 0-8108-6829-6

- ^ ISBN 1-932265-07-4

- ^

ISBN 0-89356-450-8

- ^ Mike Ashley,

"Fouqué, Friedrich (Heinrich Karl),(Baron) de la Motte",(p. 654-5) in St. James Guide To Fantasy Writers, edited by ISBN 1-55862-205-5

- ^ Veronica Ortenberg, In Search of the Holy Grail: The Quest for the Middle Ages,

(38–9) Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006, ISBN 1-85285-383-2.

- ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ISBN 0-02-053560-0

- ^ A. Richard Oliver, Charles Nodier:Pilot of Romanticism. (p. 134-37) Syracuse University Press, 1964.

- ISBN 0-8108-6829-6

- ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ^ ISBN 0-253-17461-9.

- ISBN 0-380-86553-X

- ^ ISBN 080931374X.

- ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ^ a b c Lin Carter, ed. Realms of Wizardry p 2 Doubleday and Company Garden City, NY, 1976

- ^ a b Lin Carter, ed. Kingdoms of Sorcery, p 39 Doubleday and Company Garden City, NY, 1976

- ISBN 0-253-17461-9

- ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ^ Lin Carter, ed. Realms of Wizardry p 64 Doubleday and Company Garden City, NY, 1976

- ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ISBN 0-8108-6829-6

- ISBN 0-15-667897-7

- ^ W.R. Irwin, The Game of the Impossible, p 92-3, University of Illinois Press, Urbana Chicago London, 1976

- ISBN 080931374X(pp.26–35.).

- ^ "Orchideengarten, Der". in: M.B. Tymn and Mike Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport: Greenwood, 1985. pp. 866.

ISBN 0-313-21221-X

- ISBN 1-58715-101-4

- ISBN 0-313-21221-X

- ISBN 0-313-21221-X

- ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- ISBN 0-425-05205-2

- ISBN 9780810877290. Archivedfrom the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4344-0339-1

- ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ISBN 0-89356-450-8. pp. 926–931.

- ISBN 0313335915.

- ISBN 1-932265-07-4

- ^ Lin Carter, ed. Kingdoms of Sorcery, p 121-2 Doubleday and Company Garden City, NY, 1976

- ^ Sirangelo Maggio, Sandra; Fritsch, Valter Henrique (2011). "There and Back Again: Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings in the Modern Fiction". Recorte: Revista Eletrônica. 8 (2). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "Tove Jansson: Love, war and the Moomins | BBC News". BBC News. 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Fornet-Ponse, Thomas. Tolkien's Influence on Fantasy: Interdisziplinäres Seminar Der DTG 27. Bis 29. April 2012, Jena = Tolkiens Einfluss Auf Die Moderne Fantasy. Vol. 9. Düsseldorf: Scriptorium Oxoniae., n.d. Print.

- ^ Brandon Sanderson tops best sellers list with Words of Radiance Archived 18 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine April 17, 2014

- ^ "Best-Seller Lists: Hardcover Fiction". The New York Times. 7 July 2013. Archived from the original on 12 July 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ "' 'The New York Times ' ' Best Seller list: March 20, 2011" (PDF). Hawes.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ "New York Times bestseller list". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ "Hawes' archive of New York Times bestsellers — Week of January 23, 2005" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "Indick, William. Ancient Symbology in Fantasy Literature: A Psychological Study. Jefferson: McFarland &, 2012. Print". Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ISBN 0-425-05205-2

- ISBN 0-425-05205-2

- ^ Alec Austin, "Quality in Epic Fantasy" Archived 2014-08-08 at the Wayback Machine. The generic features of historical fantasy literature, as a mode of inverting the real (including nineteenth-century ghost stories, children's stories, city comedies, classical dreams, stories of highway women, and Edens) are discussed in Writing and Fantasy, ed. Ceri Sullivan and Barbara White (London: Longman, 1999)

Works cited

- Jacobs, Joseph (1888), The earliest English version of the Fables of Bidpai, London

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ISBN 81-7224-080-5