Fas receptor

Ensembl | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt | |||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) |

| ||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | |||||||||

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 10: 88.95 – 89.03 Mb | Chr 19: 34.29 – 34.33 Mb | |||||||

| PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

The Fas receptor, also known as Fas, FasR, apoptosis antigen 1 (APO-1 or APT),

The Fas receptor is a

Gene

FAS receptor gene is located on the long arm of

Protein

Previous reports have identified as many as eight splice variants, which are translated into seven

The mature Fas protein has 319 amino acids, has a predicted molecular weight of 48 kilodaltons and is divided into three domains: an

Function

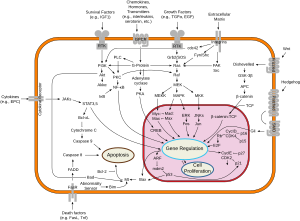

Fas forms the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) upon ligand binding. Membrane-anchored Fas ligand trimer on the surface of an adjacent cell causes oligomerization of Fas. Recent studies which suggested the trimerization of Fas could not be validated. Other models suggested the oligomerization up to 5–7 Fas molecules in the DISC.[11] This event is also mimicked by binding of an agonistic Fas antibody, though some evidence suggests that the apoptotic signal induced by the antibody is unreliable in the study of Fas signaling. To this end, several clever ways of trimerizing the antibody for in vitro research have been employed.

Upon ensuing death domain (DD) aggregation, the receptor complex is internalized via the cellular endosomal machinery. This allows the adaptor molecule FADD to bind the death domain of Fas through its own death domain.[12]

FADD also contains a

Recently, Fas has also been shown to promote tumor growth, since during tumor progression, it is frequently downregulated or cells are rendered apoptosis resistant. Cancer cells in general, regardless of their Fas apoptosis sensitivity, depend on constitutive activity of Fas. This is stimulated by cancer-produced Fas ligand for optimal growth.[14]

Although Fas has been shown to promote tumor growth in the above mouse models, analysis of the human cancer genomics database revealed that FAS is not significantly focally amplified across a dataset of 3131 tumors (FAS is not an

In cultured cells, FasL induces various types of cancer cell apoptosis through the Fas receptor. In AOM-DSS-induced colon carcinoma and MCA-induced sarcoma mouse models, it has been shown that Fas acts as a tumor suppressor.

Role in apoptosis

Some reports have suggested that the extrinsic Fas pathway is sufficient to induce complete apoptosis in certain cell types through DISC assembly and subsequent caspase-8 activation. These cells are dubbed Type 1 cells and are characterized by the inability of anti-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family (namely Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL) to protect from Fas-mediated apoptosis. Characterized Type 1 cells include H9, CH1, SKW6.4 and SW480, all of which are lymphocyte lineages except the latter, which is a colon adenocarcinoma lineage. However, evidence for crosstalk between the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways exists in the Fas signal cascade.

In most cell types, caspase-8 catalyzes the cleavage of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein

Interactions

Fas receptor has been shown to

- Caspase 8,[22][23][24]

- Caspase 10,[25]

- CFLAR,[23][24]

- FADD,[22][23][26][27][28][29]

- Fas ligand,[22][30][31][32]

- PDCD6,[33] and

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000026103 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000024778 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- PMID 1385299.

- PMID 1385309.

- PMID 15143352.

- S2CID 29449108.

- ^ "OrthoMaM phylogenetic marker: FAS coding sequence". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- PMID 16109372.

- PMID 20935634.

- S2CID 2492303.

- S2CID 4370202.

- PMID 20505730.

- ^ "Tumorscape". The Broad Institute. Archived from the original on 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- PMID 22669972.

- PMID 22461695.

- S2CID 27562316.

- PMID 9621057.

- PMID 33334730.

- PMID 28837681.

- ^ PMID 15659383.

- ^ PMID 9325248.

- ^ PMID 9208847.

- PMID 9045686.

- S2CID 19984057.

- S2CID 2492303.

- S2CID 16906755.

- PMID 12107169.

- S2CID 17145731.

- PMID 9126929.

- PMID 9228058.

- PMID 11606059.

- S2CID 38606511.

- PMID 11112409.

Further reading

- Nagata S (February 1997). "Apoptosis by death factor". Cell. 88 (3): 355–65. S2CID 494841.

- Cascino I, Papoff G, Eramo A, Ruberti G (January 1996). "Soluble Fas/Apo-1 splicing variants and apoptosis". Frontiers in Bioscience. 1 (4): d12-8. PMID 9159204.

- Uckun FM (September 1998). "Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) as a dual-function regulator of apoptosis". Biochemical Pharmacology. 56 (6): 683–91. PMID 9751072.

- Krammer PH (October 2000). "CD95's deadly mission in the immune system". Nature. 407 (6805): 789–95. S2CID 4328897.

- Siegel RM, Chan FK, Chun HJ, Lenardo MJ (December 2000). "The multifaceted role of Fas signaling in immune cell homeostasis and autoimmunity". Nature Immunology. 1 (6): 469–74. S2CID 345769.

- Yonehara S (2003). "Death receptor Fas and autoimmune disease: from the original generation to therapeutic application of agonistic anti-Fas monoclonal antibody". Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 13 (4–5): 393–402. PMID 12220552.

- Choi C, Benveniste EN (January 2004). "Fas ligand/Fas system in the brain: regulator of immune and apoptotic responses". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 44 (1): 65–81. S2CID 46587211.

- Poppema S, Maggio E, van den Berg A (March 2004). "Development of lymphoma in Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome (ALPS) and its relationship to Fas gene mutations". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 45 (3): 423–31. S2CID 35128360.

External links

- FAS+Receptor at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P25445 (Human Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6) at the PDBe-KB.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P25446 (Mouse Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6) at the PDBe-KB.