Fat

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

| Components |

| Manufactured fats |

In

The term often refers specifically to

Fats are one of the three main

Biological importance

In humans and many animals, fats serve both as energy sources and as stores for energy in excess of what the body needs immediately. Each gram of fat when burned or metabolized releases about 9

Fats are also sources of essential fatty acids, an important dietary requirement. Vitamins A, D, E, and K are fat-soluble, meaning they can only be digested, absorbed, and transported in conjunction with fats.

Fats play a vital role in maintaining healthy

Adipose tissue

In animals,

Production and processing

A variety of chemical and physical techniques are used for the production and processing of fats, both industrially and in cottage or home settings. They include:

- Solvent extraction using solvents like hexane or supercritical carbon dioxide

- Rendering, the melting of fat in adipose tissue, e.g. to produce tallow, lard, fish oil, and whale oil

- Churning of milk to produce butter

- Hydrogenation to increase the degree of saturation of the fatty acids

- Interesterification, the rearrangement of fatty acids across different triglycerides

- Winterizationto remove oil components with higher melting points

- Clarification of butter

Metabolism

The

In the

Triglycerides cannot pass through cell membranes freely. Special enzymes on the walls of blood vessels called lipoprotein lipases must break down triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol. Fatty acids can then be taken up by cells via fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs).

Triglycerides, as major components of

Nutritional and health aspects

The most common type of fat, in human diet and most living beings, is a

2O.

Other less common types of fats include diglycerides and monoglycerides, where the esterification is limited to two or just one of glycerol's –OH groups. Other alcohols, such as cetyl alcohol (predominant in spermaceti), may replace glycerol. In the phospholipids, one of the fatty acids is replaced by phosphoric acid or a monoester thereof. The benefits and risks of various amounts and types of dietary fats have been the object of much study, and are still highly controversial topics.[10][11][12][13]

Essential fatty acids

There are two

The adult body can synthesize other lipids that it needs from these two.Dietary sources

| Type | Processing treatment[17] |

Saturated fatty acids |

Monounsaturated fatty acids |

Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

Smoke point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total[15] | Oleic acid (ω-9) |

Total[15] | α-Linolenic acid (ω-3) |

Linoleic acid (ω-6) |

ω-6:3 ratio | ||||

| Avocado[18] | 11.6 | 70.6 | 52–66 [19] |

13.5 | 1 | 12.5 | 12.5:1 | 250 °C (482 °F)[20] | |

| Brazil nut[21] | 24.8 | 32.7 | 31.3 | 42.0 | 0.1 | 41.9 | 419:1 | 208 °C (406 °F)[22] | |

| Canola[23] | 7.4 | 63.3 | 61.8 | 28.1 | 9.1 | 18.6 | 2:1 | 204 °C (400 °F)[24] | |

| Coconut[25] | 82.5 | 6.3 | 6 | 1.7 | 0.019 | 1.68 | 88:1 | 175 °C (347 °F)[22] | |

| Corn[26] | 12.9 | 27.6 | 27.3 | 54.7 | 1 | 58 | 58:1 | 232 °C (450 °F)[24] | |

| Cottonseed[27] | 25.9 | 17.8 | 19 | 51.9 | 1 | 54 | 54:1 | 216 °C (420 °F)[24] | |

| Cottonseed[28] | hydrogenated |

93.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.5:1 | ||

| Flaxseed/linseed[29] | 9.0 | 18.4 | 18 | 67.8 | 53 | 13 | 0.2:1 | 107 °C (225 °F) | |

| Grape seed | 10.4 | 14.8 | 14.3 | 74.9 | 0.15 | 74.7 | very high | 216 °C (421 °F)[30] | |

| Hemp seed[31] | 7.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 82.0 | 22.0 | 54.0 | 2.5:1 | 166 °C (330 °F)[32] | |

High-oleic safflower oil[33] |

7.5 | 75.2 | 75.2 | 12.8 | 0 | 12.8 | very high | 212 °C (414 °F)[22] | |

| Olive, Extra Virgin[34] | 13.8 | 73.0 | 71.3 | 10.5 | 0.7 | 9.8 | 14:1 | 193 °C (380 °F)[22] | |

| Palm[35] | 49.3 | 37.0 | 40 | 9.3 | 0.2 | 9.1 | 45.5:1 | 235 °C (455 °F) | |

| Palm[36] | hydrogenated | 88.2 | 5.7 | 0 | |||||

| Peanut[37] | 16.2 | 57.1 | 55.4 | 19.9 | 0.318 | 19.6 | 61.6:1 | 232 °C (450 °F)[24] | |

| Rice bran oil | 25 | 38.4 | 38.4 | 36.6 | 2.2 | 34.4[38] | 15.6:1 | 232 °C (450 °F)[39] | |

| Sesame[40] | 14.2 | 39.7 | 39.3 | 41.7 | 0.3 | 41.3 | 138:1 | ||

| Soybean[41] | 15.6 | 22.8 | 22.6 | 57.7 | 7 | 51 | 7.3:1 | 238 °C (460 °F)[24] | |

| Soybean[42] | partially hydrogenated |

14.9 | 43.0 | 42.5 | 37.6 | 2.6 | 34.9 | 13.4:1 | |

| Sunflower[43] | 8.99 | 63.4 | 62.9 | 20.7 | 0.16 | 20.5 | 128:1 | 227 °C (440 °F)[24] | |

| Walnut oil[44] | unrefined | 9.1 | 22.8 | 22.2 | 63.3 | 10.4 | 52.9 | 5:1 | 160 °C (320 °F)[45] |

Saturated vs. unsaturated fats

Different foods contain different amounts of fat with different proportions of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. Some animal products, like

Plants and fish oil generally contain a higher proportion of unsaturated acids, although there are exceptions such as

Many careful studies have found that replacing saturated fats with cis unsaturated fats in the diet reduces risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs),[51][52] diabetes, or death.[53] These studies prompted many medical organizations and public health departments, including the World Health Organization (WHO),[54][55] to officially issue that advice. Some countries with such recommendations include:

- United Kingdom[56][57][58][59][60]

- United States[53][61][62][63][64]

- India[65][66]

- Canada[67]

- Australia[68]

- Singapore[69]

- New Zealand[70]

- Hong Kong[71]

A 2004 review concluded that "no lower safe limit of specific saturated fatty acid intakes has been identified" and recommended that the influence of varying saturated fatty acid intakes against a background of different individual lifestyles and genetic backgrounds should be the focus in future studies.[72]

This advice is often oversimplified by labeling the two kinds of fats as bad fats and good fats, respectively. However, since the fats and oils in most natural and traditionally processed foods contain both unsaturated and saturated fatty acids,[73] the complete exclusion of saturated fat is unrealistic and possibly unwise. For instance, some foods rich in saturated fat, such as coconut and palm oil, are an important source of cheap dietary calories for a large fraction of the population in developing countries.[74]

Concerns were also expressed at a 2010 conference of the

For these reasons, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, for example, recommends to consume at least 10% (7% for high-risk groups) of calories from saturated fat, with an average of 30% (or less) of total calories from all fat.[76][74] A general 7% limit was recommended also by the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2006.[77][78]

The WHO/FAO report also recommended replacing fats so as to reduce the content of myristic and palmitic acids, specifically.[74]

The so-called Mediterranean diet, prevalent in many countries in the Mediterranean Sea area, includes more total fat than the diet of Northern European countries, but most of it is in the form of unsaturated fatty acids (specifically, monounsaturated and omega-3) from olive oil and fish, vegetables, and certain meats like lamb, while consumption of saturated fat is minimal in comparison. A 2017 review found evidence that a Mediterranean-style diet could reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases, overall cancer incidence, neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes, and mortality rate.[79] A 2018 review showed that a Mediterranean-like diet may improve overall health status, such as reduced risk of non-communicable diseases. It also may reduce the social and economic costs of diet-related illnesses.[80]

A small number of contemporary reviews have challenged this negative view of saturated fats. For example, an evaluation of evidence from 1966 to 1973 of the observed health impact of replacing dietary saturated fat with linoleic acid found that it increased rates of death from all causes, coronary heart disease, and cardiovascular disease.[81] These studies have been disputed by many scientists,[82] and the consensus in the medical community is that saturated fat and cardiovascular disease are closely related.[83][84][85] Still, these discordant studies fueled debate over the merits of substituting polyunsaturated fats for saturated fats.[86]

Cardiovascular disease

The effect of saturated fat on cardiovascular disease has been extensively studied.

A 2017 review by the AHA estimated that replacement of saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat in the American diet could reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases by 30%.[53]

The consumption of saturated fat is generally considered a risk factor for dyslipidemia—abnormal blood lipid levels, including high total cholesterol, high levels of triglycerides, high levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL, "bad" cholesterol) or low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL, "good" cholesterol). These parameters in turn are believed to be risk indicators for some types of cardiovascular disease.[96][97][98][99][100][92][101][102][103] These effects were observed in children too.[104]

Several

Cancer

The evidence for a relation between saturated fat intake and cancer is significantly weaker, and there does not seem to be a clear medical consensus about it.

- A meta-analysis published in 2003 found a

- Another review found limited evidence for a positive relationship between consuming animal fat and incidence of colorectal cancer.[115]

- Other meta-analyses found evidence for increased risk of ovarian cancer by high consumption of saturated fat.[116]

- Some studies have indicated that serum myristic acid[117][118] and palmitic acid[118] and dietary myristic[119] and palmitic[119] saturated fatty acids and serum palmitic combined with alpha-tocopherol supplementation[117] are associated with increased risk of prostate cancer in a dose-dependent manner. These associations may, however, reflect differences in intake or metabolism of these fatty acids between the precancer cases and controls, rather than being an actual cause.[118]

Bones

Various animal studies have indicated that the intake of saturated fat has a negative effect on the mineral density of bones. One study suggested that men may be particularly vulnerable.[120]

Disposition and overall health

Studies have shown that substituting monounsaturated fatty acids for saturated ones is associated with increased daily physical activity and resting energy expenditure. More physical activity, less anger, and less irritability were associated with a higher-oleic acid diet than one of a palmitic acid diet.[121]

Monounsaturated vs. polyunsaturated fat

The most common fatty acids in human diet are unsaturated or mono-unsaturated. Monounsaturated fats are found in animal flesh such as red

Polyunsaturated fatty acids can be found mostly in nuts, seeds, fish, seed oils, and oysters.[128]

Food sources of polyunsaturated fats include:[128][129]

| Food source (100g) | Polyunsaturated fat (g) |

|---|---|

Walnuts |

47 |

Canola oil |

34 |

| Sunflower seeds | 33 |

Sesame seeds |

26 |

| Chia seeds | 23.7 |

| Unsalted peanuts | 16 |

| Peanut butter | 14.2 |

| Avocado oil | 13.5[130] |

| Olive oil | 11 |

Safflower oil

|

12.82[131] |

| Seaweed | 11 |

Sardines |

5 |

Soybeans |

7 |

| Tuna | 14 |

| Wild salmon | 17.3 |

| Whole grain wheat | 9.7 |

Insulin resistance and sensitivity

MUFAs (especially oleic acid) have been found to lower the incidence of

The large scale KANWU study found that increasing MUFA and decreasing SFA intake could improve insulin sensitivity, but only when the overall fat intake of the diet was low.[132] However, some MUFAs may promote insulin resistance (like the SFAs), whereas PUFAs may protect against it.[133][134][clarification needed]

Cancer

Levels of oleic acid along with other MUFAs in red blood cell membranes were positively associated with breast cancer risk. The

Results from observational clinical trials on PUFA intake and cancer have been inconsistent and vary by numerous factors of cancer incidence, including gender and genetic risk.[136] Some studies have shown associations between higher intakes and/or blood levels of omega-3 PUFAs and a decreased risk of certain cancers, including breast and colorectal cancer, while other studies found no associations with cancer risk.[136][137]

Pregnancy disorders

Polyunsaturated fat supplementation was found to have no effect on the incidence of pregnancy-related disorders, such as

Expert panels in the United States and Europe recommend that pregnant and lactating women consume higher amounts of polyunsaturated fats than the general population to enhance the DHA status of the fetus and newborn.[128]

"Cis fat" vs. "trans fat"

In nature, unsaturated fatty acids generally have double bonds in cis configuration (with the adjacent C–C bonds on the same side) as opposed to trans.[138] Nevertheless, trans fatty acids (TFAs) occur in small amounts in meat and milk of ruminants (such as cattle and sheep),[139][140] typically 2–5% of total fat.[141] Natural TFAs, which include conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and vaccenic acid, originate in the rumen of these animals. CLA has two double bonds, one in the cis configuration and one in trans, which makes it simultaneously a cis- and a trans-fatty acid.[142]

| Food type | Trans fat content |

|---|---|

| butter | 2 to 7 g |

| whole milk | 0.07 to 0.1 g |

| animal fat | 0 to 5 g[141] |

| ground beef | 1 g |

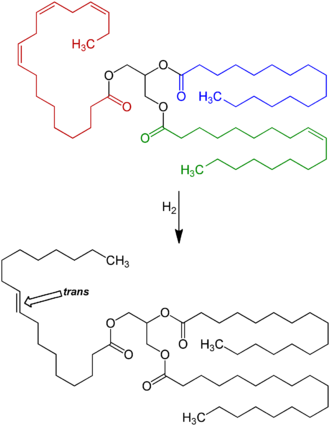

Concerns about trans fatty acids in human diet were raised when they were found to be an unintentional byproduct of the partial hydrogenation of vegetable and fish oils. While these trans fatty acids (popularly called "trans fats") are edible, they have been implicated in many health problems.[144]

The hydrogenation process, invented and patented by Wilhelm Normann in 1902, made it possible to turn relatively cheap liquid fats such as whale or fish oil into more solid fats and to extend their shelf-life by preventing rancidification. (The source fat and the process were initially kept secret to avoid consumer distaste.[145]) This process was widely adopted by the food industry in the early 1900s; first for the production of margarine, a replacement for butter and shortening,[146] and eventually for various other fats used in snack food, packaged baked goods, and deep fried products.[147]

Full hydrogenation of a fat or oil produces a fully saturated fat. However, hydrogenation generally was interrupted before completion, to yield a fat product with specific melting point, hardness, and other properties. Partial hydrogenation turns some of the cis double bonds into trans bonds by an

] because it is the lower energy form.This side reaction accounts for most of the trans fatty acids consumed today, by far.[149][150] An analysis of some industrialized foods in 2006 found up to 30% "trans fats" in artificial shortening, 10% in breads and cake products, 8% in cookies and crackers, 4% in salty snacks, 7% in cake frostings and sweets, and 26% in margarine and other processed spreads.[143] Another 2010 analysis however found only 0.2% of trans fats in margarine and other processed spreads.[151] Up to 45% of the total fat in those foods containing man-made trans fats formed by partially hydrogenating plant fats may be trans fat.[141] Baking shortenings, unless reformulated, contain around 30% trans fats compared to their total fats. High-fat dairy products such as butter contain about 4%. Margarines not reformulated to reduce trans fats may contain up to 15% trans fat by weight,[152] but some reformulated ones are less than 1% trans fat.

High levels of TFAs have been recorded in popular "fast food" meals.

Cardiovascular disease

Numerous studies have found that consumption of TFAs increases risk of cardiovascular disease.

Consuming trans fats has been shown to increase the risk of coronary artery disease in part by raising levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL, often termed "bad cholesterol"), lowering levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL, often termed "good cholesterol"), increasing triglycerides in the bloodstream and promoting systemic inflammation.[155][156]

The primary health risk identified for trans fat consumption is an elevated risk of

The major evidence for the effect of trans fat on CAD comes from the Nurses' Health Study – a cohort study that has been following 120,000 female nurses since its inception in 1976. In this study, Hu and colleagues analyzed data from 900 coronary events from the study's population during 14 years of followup. He determined that a nurse's CAD risk roughly doubled (relative risk of 1.93, CI: 1.43 to 2.61) for each 2% increase in trans fat calories consumed (instead of carbohydrate calories). By contrast, for each 5% increase in saturated fat calories (instead of carbohydrate calories) there was a 17% increase in risk (relative risk of 1.17, CI: 0.97 to 1.41). "The replacement of saturated fat or trans unsaturated fat by cis (unhydrogenated) unsaturated fats was associated with larger reductions in risk than an isocaloric replacement by carbohydrates."[161] Hu also reports on the benefits of reducing trans fat consumption. Replacing 2% of food energy from trans fat with non-trans unsaturated fats more than halves the risk of CAD (53%). By comparison, replacing a larger 5% of food energy from saturated fat with non-trans unsaturated fats reduces the risk of CAD by 43%.[161]

Another study considered deaths due to CAD, with consumption of trans fats being linked to an increase in mortality, and consumption of polyunsaturated fats being linked to a decrease in mortality.[157][162]

Trans fat has been found to act like saturated in raising the blood level of LDL ("bad cholesterol"); but, unlike saturated fat, it also decreases levels of HDL ("good cholesterol"). The net increase in LDL/HDL ratio with trans fat, a widely accepted indicator of risk for coronary artery disease, is approximately double that due to saturated fat.

The citokyne test is a potentially more reliable indicator of CAD risk, although is still being studied.[157] A study of over 700 nurses showed that those in the highest quartile of trans fat consumption had blood levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) that were 73% higher than those in the lowest quartile.[167]

Breast feeding

It has been established that trans fats in human breast milk fluctuate with maternal consumption of trans fat, and that the amount of trans fats in the bloodstream of breastfed infants fluctuates with the amounts found in their milk. In 1999, reported percentages of trans fats (compared to total fats) in human milk ranged from 1% in Spain, 2% in France, 4% in Germany, and 7% in Canada and the United States.[168]

Other health risks

There are suggestions that the negative consequences of trans fat consumption go beyond the cardiovascular risk. In general, there is much less scientific consensus asserting that eating trans fat specifically increases the risk of other chronic health problems:

- Archives of Neurology in February 2003 suggested that the intake of both trans fats and saturated fats promotes the development of Alzheimer disease,[169] although not confirmed in an animal model.[170] It has been found that trans fats impaired memory and learning in middle-age rats. The brains of rats that ate trans-fats had fewer proteins critical to healthy neurological function. Inflammation in and around the hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for learning and memory. These are the exact types of changes normally seen at the onset of Alzheimer's, but seen after six weeks, even though the rats were still young.[171]

- Cancer: There is no scientific consensus that consuming trans fats significantly increases cancer risks across the board.[157] The American Cancer Society states that a relationship between trans fats and cancer "has not been determined."[172] One study has found a positive connection between trans fat and prostate cancer.[173] However, a larger study found a correlation between trans fats and a significant decrease in high-grade prostate cancer.[174] An increased intake of trans fatty acids may raise the risk of breast cancer by 75%, suggest the results from the French part of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition.[175][176]

- type 2 diabetes increases with trans fat consumption.[157][177] However, consensus has not been reached.[160] For example, one study found that risk is higher for those in the highest quartile of trans fat consumption.[178] Another study has found no diabetes risk once other factors such as total fat intake and BMI were accounted for.[179]

- Obesity: Research indicates that trans fat may increase weight gain and abdominal fat, despite a similar caloric intake.[180] A 6-year experiment revealed that monkeys fed a trans fat diet gained 7.2% of their body weight, as compared to 1.8% for monkeys on a mono-unsaturated fat diet.[181][182] Although obesity is frequently linked to trans fat in the popular media,[183] this is generally in the context of eating too many calories; there is not a strong scientific consensus connecting trans fat and obesity, although the 6-year experiment did find such a link, concluding that "under controlled feeding conditions, long-term TFA consumption was an independent factor in weight gain. TFAs enhanced intra-abdominal deposition of fat, even in the absence of caloric excess, and were associated with insulin resistance, with evidence that there is impaired post-insulin receptor binding signal transduction."[182]

- Infertility in women: One 2007 study found, "Each 2% increase in the intake of energy from trans unsaturated fats, as opposed to that from carbohydrates, was associated with a 73% greater risk of ovulatory infertility...".[184]

- reward, reward expectation, and empathy (all of which are reduced in depressive mood disorders) and regulates the limbic system.[186]

- Behavioral irritability and aggression: a 2012 observational analysis of subjects of an earlier study found a strong relation between dietary trans fat acids and self-reported behavioral aggression and irritability, suggesting but not establishing causality.[187]

- Diminished memory: In a 2015 article, researchers re-analyzing results from the 1999-2005 UCSD Statin Study argue that "greater dietary trans fatty acid consumption is linked to worse word memory in adults during years of high productivity, adults age <45".[188]

- Acne: According to a 2015 study, trans fats are one of several components of Western pattern diets which promote acne, along with carbohydrates with high glycemic load such as refined sugars or refined starches, milk and dairy products, and saturated fats, while omega-3 fatty acids, which reduce acne, are deficient in Western pattern diets.[189]

Biochemical mechanisms

The exact biochemical process by which trans fats produce specific health problems are a topic of continuing research. Intake of dietary trans fat perturbs the body's ability to metabolize essential fatty acids (EFAs, including omega-3) leading to changes in the phospholipid fatty acid composition of the arterial walls, thereby raising risk of coronary artery disease.[190]

Trans double bonds are claimed to induce a linear conformation to the molecule, favoring its rigid packing as in plaque formation. The geometry of the cis double bond, in contrast, is claimed to create a bend in the molecule, thereby precluding rigid formations.[191]

While the mechanisms through which trans fatty acids contribute to coronary artery disease are fairly well understood, the mechanism for their effects on diabetes is still under investigation. They may impair the metabolism of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs).[192] However, maternal pregnancy trans fatty acid intake has been inversely associated with LCPUFAs levels in infants at birth thought to underlie the positive association between breastfeeding and intelligence.[193]

Trans fats are processed by the

Natural "trans fats" in dairy products

Some trans fatty acids occur in natural fats and traditionally processed foods.

The U.S. National Dairy Council has asserted that the trans fats present in animal foods are of a different type than those in partially hydrogenated oils, and do not appear to exhibit the same negative effects.[196] A review agrees with the conclusion (stating that "the sum of the current evidence suggests that the Public health implications of consuming trans fats from ruminant products are relatively limited") but cautions that this may be due to the low consumption of trans fats from animal sources compared to artificial ones.[160]

In 2008 a meta-analysis found that all trans fats, regardless of natural or artificial origin equally raise LDL and lower HDL levels.[197] Other studies though have shown different results when it comes to animal-based trans fats like conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). Although CLA is known for its anticancer properties, researchers have also found that the cis-9, trans-11 form of CLA can reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease and help fight inflammation.[198][199]

Two Canadian studies have shown that vaccenic acid, a TFA that naturally occurs in dairy products, could be beneficial compared to hydrogenated vegetable shortening, or a mixture of pork lard and soy fat, by lowering total LDL and triglyceride levels.[200][201][202] A study by the US Department of Agriculture showed that vaccenic acid raises both HDL and LDL cholesterol, whereas industrial trans fats only raise LDL with no beneficial effect on HDL.[203]

Official recommendations

In light of recognized evidence and scientific agreement, nutritional authorities consider all trans fats equally harmful for health and recommend that their consumption be reduced to trace amounts.[204][205][206][207][208] In 2003, the WHO recommended that trans fats make up no more than 0.9% of a person's diet[141] and, in 2018, introduced a 6-step guide to eliminate industrially-produced trans-fatty acids from the global food supply.[209]

The

Their recommendations are based on two key facts. First, "trans fatty acids are not essential and provide no known benefit to human health",

Because of these facts and concerns, the NAS has concluded there is no safe level of trans fat consumption. There is no adequate level, recommended daily amount or tolerable upper limit for trans fats. This is because any incremental increase in trans fat intake increases the risk of coronary artery disease.[156]

Despite this concern, the NAS dietary recommendations have not included eliminating trans fat from the diet. This is because trans fat is naturally present in many animal foods in trace quantities, and thus its removal from ordinary diets might introduce undesirable side effects and nutritional imbalances. The NAS has, thus, "recommended that trans fatty acid consumption be as low as possible while consuming a nutritionally adequate diet".[213] Like the NAS, the WHO has tried to balance public health goals with a practical level of trans fat consumption, recommending in 2003 that trans fats be limited to less than 1% of overall energy intake.[141]

Regulatory action

In the last few decades, there has been substantial amount of regulation in many countries, limiting trans fat contents of industrialized and commercial food products.

Alternatives to hydrogenation

The negative public image and strict regulations has led to interest in replacing partial hydrogenation. In fat interesterification, the fatty acids are among a mix of triglycerides. When applied to a suitable blend of oils and saturated fats, possibly followed by separation of unwanted solid or liquid triglycerides, this process could conceivably achieve results similar to those of partial hydrogenation without affecting the fatty acids themselves; in particular, without creating any new "trans fat".

Hydrogenation can be achieved with only small production of trans fat. The high-pressure methods produced margarine containing 5 to 6% trans fat. Based on current U.S. labeling requirements (see below), the manufacturer could claim the product was free of trans fat.[214] The level of trans fat may also be altered by modification of the temperature and the length of time during hydrogenation.

One can mix oils (such as olive, soybean, and canola), water, monoglycerides, and fatty acids to form a "cooking fat" that acts the same way as trans and saturated fats.[215][216]

Omega-three and omega-six fatty acids

The

Interesterification

Some studies have investigated the health effects of interesterified (IE) fats, by comparing diets with IE and non-IE fats with the same overall fatty acid composition.[218]

Several experimental studies in humans found no statistical difference on fasting blood lipids between a diet with large amounts of IE fat, having 25-40% C16:0 or C18:0 on the 2-position, and a similar diet with non-IE fat, having only 3-9% C16:0 or C18:0 on the 2-position.[219][220][221] A negative result was obtained also in a study that compared the effects on blood cholesterol levels of an IE fat product mimicking cocoa butter and the real non-IE product.[222][223][224][225][226][227][228]

A 2007 study funded by the Malaysian Palm Oil Board[229] claimed that replacing natural palm oil by other interesterified or partially hydrogenated fats caused adverse health effects, such as higher LDL/HDL ratio and plasma glucose levels. However, these effects could be attributed to the higher percentage of saturated acids in the IE and partially hydrogenated fats, rather than to the IE process itself.[230][231]

Role in disease

In the human body, high levels of triglycerides in the bloodstream have been linked to

Guidelines

The National Cholesterol Education Program has set guidelines for triglyceride levels:[234][235]

| Level | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|

| ( dL )

|

(mmol/L) | |

| < 150 | < 1.70 | Normal range – low risk |

| 150–199 | 1.70–2.25 | Slightly above normal |

| 200–499 | 2.26–5.65 | Some risk |

| 500 or higher | > 5.65 | Very high – high risk |

These levels are tested after fasting 8 to 12 hours. Triglyceride levels remain temporarily higher for a period after eating.

The AHA recommends an optimal triglyceride level of 100 mg/dL (1.1 mmol/L) or lower to improve heart health.[236]

Reducing triglyceride levels

Weight loss and dietary modification are effective first-line lifestyle modification treatments for hypertriglyceridemia.[237] For people with mildly or moderately high levels of triglycerides, lifestyle changes, including weight loss, moderate exercise[238][239] and dietary modification, are recommended.[240] This may include restriction of carbohydrates (specifically fructose)[237] and fat in the diet and the consumption of omega-3 fatty acids[239] from algae, nuts, fish and seeds.[241] Medications are recommended in those with high levels of triglycerides that are not corrected with the aforementioned lifestyle modifications, with fibrates being recommended first.[240][242][243] Omega-3-carboxylic acids is another prescription drug used to treat very high levels of blood triglycerides.[244]

The decision to treat hypertriglyceridemia with medication depends on the levels and on the presence of other risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Very high levels that would increase the risk of pancreatitis are treated with a drug from the

Fat digestion and metabolism

Fats are broken down in the healthy body to release their constituents,

Many cell types can use either glucose or fatty acids as a source of energy for metabolism. In particular, heart and skeletal muscle prefer fatty acids.[citation needed] Despite long-standing assertions to the contrary, fatty acids can also be used as a source of fuel for brain cells through mitochondrial oxidation.[245]

See also

- Animal fat

- Monounsaturated fat

- Diet and heart disease

- Fatty acid synthesis

- Food composition data

- Western pattern diet

- Oil

- Lipid

References

- ^ a b c d Entry for "fat" Archived 2020-07-25 at the Wayback Machine in the online Merriam-Webster disctionary, sense 3.2. Accessed on 2020-08-09

- ^

- University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Archived from the originalon 21 September 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ "Introduction to Energy Storage". Khan Academy.

- ^ a b c Government of the United Kingdom (1996): "Schedule 7: Nutrition labelling Archived 2013-03-17 at the Wayback Machine". In Food Labelling Regulations 1996 Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed on 2020-08-09.

- PMID 28413578.

- ^ "The human proteome in adipose - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- PMID 21489321.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-470-05242-6.

- ISBN 978-0-13-120687-8

- ^ PMID 16611951

- ^ a b c "US National Nutrient Database, Release 28". United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. All values in this table are from this database unless otherwise cited or when italicized as the simple arithmetic sum of other component columns.

- ^ "Fats and fatty acids contents per 100 g (click for "more details"). Example: Avocado oil (user can search for other oils)". Nutritiondata.com, Conde Nast for the USDA National Nutrient Database, Standard Release 21. 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2017. Values from Nutritiondata.com (SR 21) may need to be reconciled with most recent release from the USDA SR 28 as of Sept 2017.

- ^ "USDA Specifications for Vegetable Oil Margarine Effective August 28, 1996" (PDF).

- ^ "Avocado oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ Ozdemir F, Topuz A (2004). "Changes in dry matter, oil content and fatty acids composition of avocado during harvesting time and post-harvesting ripening period" (PDF). Food Chemistry. Elsevier. pp. 79–83. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-16. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ Wong M, Requejo-Jackman C, Woolf A (April 2010). "What is unrefined, extra virgin cold-pressed avocado oil?". Aocs.org. The American Oil Chemists' Society. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ "Brazil nut oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ .

- ^ "Canola oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Wolke RL (May 16, 2007). "Where There's Smoke, There's a Fryer". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ "Coconut oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Corn oil, industrial and retail, all purpose salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Cottonseed oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Cottonseed oil, industrial, fully hydrogenated, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Linseed/Flaxseed oil, cold pressed, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- PMID 27559299.

- S2CID 18445488.

- ^ Melina V. "Smoke points of oils" (PDF). veghealth.com. The Vegetarian Health Institute.

- ^ "Safflower oil, salad or cooking, high oleic, primary commerce, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Olive oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Palm oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Palm oil, industrial, fully hydrogenated, filling fat, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Oil, peanut". FoodData Central. usda.gov.

- ISBN 978-0-471-38552-3.

- ^ "Rice bran oil". RITO Partnership. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Oil, sesame, salad or cooking". FoodData Central. fdc.nal.usda.gov. 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Soybean oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Soybean oil, salad or cooking, (partially hydrogenated), fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "FoodData Central". fdc.nal.usda.gov.

- ^ "Walnut oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ "Smoke Point of Oils". Baseline of Health. Jonbarron.org.

- ^ "Saturated fats". American Heart Association. 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Top food sources of saturated fat in the US". Harvard University School of Public Health. 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Saturated, Unsaturated, and Trans Fats". choosemyplate.gov. 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-10-15. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ISBN 978-0-8053-6624-2.

- ^ "What are "oils"?". ChooseMyPlate.gov, US Department of Agriculture. 2015. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- PMID 26068959.

- PMID 32827219.

- ^ S2CID 367602.

- ^ "Healthy diet Fact sheet N°394". May 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ World Health Organization: Food pyramid (nutrition)

- ^ "Fats explained" (PDF). HEART UK – The Cholesterol Charity. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-02-21. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Live Well, Eat well, Fat: the facts". NHS. 27 April 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Fat: the facts". United Kingdom's National Health Service. 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "How to eat less saturated fat - NHS". nhs.uk. April 27, 2018.

- ^ "Fats explained - types of fat | BHF".

- ^ "Key Recommendations: Components of Healthy Eating Patterns". Dietary Guidelines 2015-2020. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Cut Down on Saturated Fats" (PDF). United States Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- Centers for Disease Control. 2004. Archived from the originalon 2008-12-01.

- ^ "Dietary Guidelines for Americans" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. 2005.

- ^ "Dietary Guidelines for Indians - A Manual" (PDF). Indian Council of Medical Research, National Institute of Nutrition. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-22. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- ^ "Health Diet". India's Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Archived from the original on 2016-08-06. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Choosing foods with healthy fats". Health Canada. 2018-10-10. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Fat". Australia's National Health and Medical Research Council and Department of Health and Ageing. 2012-09-24. Archived from the original on 2013-02-23. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Getting the Fats Right!". Singapore's Ministry of Health. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults" (PDF). New Zealand's Ministry of Health. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Know More about Fat". Hong Kong's Department of Health. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- PMID 15321792.

- ^ S2CID 33171616.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-4-120916-8. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2013-04-21. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- PMID 21515106.

- ^ Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (2022-03-07). "Health Claim Notification for Saturated Fat, Cholesterol, and Trans Fat, and Reduced Risk of Heart Disease". FDA.

- S2CID 647269.

- PMID 15226228.

- S2CID 7702206.

- PMID 29992229.

- PMID 23386268.

- ^ Interview: Walter Willett (2017). "Research Review: Old data on dietary fats in context with current recommendations: Comments on Ramsden et al. in the British Medical Journal". TH Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University, Boston. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- PMID 26268692.

- PMID 23386268.

- PMID 27071971.

- PMID 26301240.

- ^ PMID 32428300.

- PMID 17726041.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- PMID 17936958.

- ^ "Food Fact Sheet - Cholesterol" (PDF). British Dietetic Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-11-22. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors". World Heart Federation. 30 May 2017. Archived from the original on 2012-05-10. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Lower your cholesterol". National Health Service. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Nutrition Facts at a Glance - Nutrients: Saturated Fat". Food and Drug Administration. 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol". European Food Safety Authority. 2010-03-25. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom. "Position Statement on Fat" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ^ Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003). "Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 4, 2003. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ^ "Cholesterol". Irish Heart Foundation. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ^ U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (December 2010). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 (PDF) (7th ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Cannon C, O'Gara P (2007). Critical Pathways in Cardiovascular Medicine (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 243.

- PMID 21723445.

- ^ "Monounsaturated Fat". American Heart Association. Archived from the original on 2018-03-07. Retrieved 2018-04-19.

- ^ "You Can Control Your Cholesterol: A Guide to Low-Cholesterol Living". MerckSource. Archived from the original on 2009-03-03. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- S2CID 8798248.

- PMID 9006469.

- PMID 9974397.

- ^ S2CID 54293528.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- PMID 16596799.

- PMID 14583769.

- ^ PMID 16316809.

- S2CID 9513690.

- PMID 18391610.

- PMID 19107442.

- S2CID 24890525.

- ^ PMID 14693732.

- ^ PMID 18996872.

- ^ S2CID 551427.

- S2CID 4443420.

- PMID 23446891.

- PMID 28158733.

- PMID 26567193.

- ^ Shute, Nancy (2012-05-02). "Lard Is Back In The Larder, But Hold The Health Claims". NPR. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- PMID 25032409.

- ^ "Ask the Expert: Concerns about canola oil". The Nutrition Source. 2015-04-13. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- PMID 25471637.

- ^ a b c d e "Essential Fatty Acids". Micronutrient Information Center, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "National nutrient database for standard reference, release 23". United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2011. Archived from the original on 2015-03-03. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ^ "Vegetable oil, avocado Nutrition Facts & Calories". nutritiondata.self.com.

- ^ "United States Department of Agriculture – National Nutrient Database". 8 September 2015. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016.

- PMID 11317662.

- S2CID 31329463.

- S2CID 20966659.

- ^ PMID 11459870.

- ^ a b "Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Health: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". US National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. 2 November 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- PMID 21178081.

- PMID 17625687.

- PMID 22164125.

- ISBN 978-1-4251-3808-0.

- ^ ISBN 0-662-43689-X. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ^ "DIETA DETOX ✅ QUÉ ES Y SUS 13 PODEROSOS BENEFICIOS". October 24, 2019.

- ^ PMID 16720128.

- S2CID 206968361.

- ^ "Wilhelm Normann und die Geschichte der Fetthärtung von Martin Fiedler, 2001". 20 December 2011. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- ISBN 978-1-60327-571-2.

- ^ a b "Tentative Determination Regarding Partially Hydrogenated Oils". Federal Register. 8 November 2013. 2013-26854, Vol. 78, No. 217. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-13-605449-8.

- ISBN 978-93-80026-37-4.

- ^ PMID 10983247.

- ^ "Heart Foundation: Butter has 20 times the trans fats of marg | Australian Food News". www.ausfoodnews.com.au.

- .

- PMID 16611965.

- ^ "Fats and Cholesterol" Archived 2016-11-18 at the Wayback Machine, Harvard School of Public Health. Retrieved 02-11-16.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-309-08525-0.

- ^ a b c Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids (macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. 504.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Trans Fat Task Force (June 2006). "Appendix 9iii)". TRANSforming the Food Supply. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2007. (Consultation on the health implications of alternatives to trans fatty acids: Summary of Responses from Experts)

- PMID 8179036.

- PMID 16998148.

- ^ S2CID 35121566.

- ^ PMID 9366580.

- PMID 15781956.

- S2CID 30165590.

- PMID 2374566.

- PMID 12716665.

- PMID 12716661.

- PMID 15735094.

- PMID 10479201.

- PMID 12580703.

- ^ S2CID 35748183.

- PMID 18560126.

- ^ American Cancer Society. "Common questions about diet and cancer". Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ Chavarro J, Stampfer M, Campos H, Kurth T, Willett W, Ma J (1 April 2006). "A prospective study of blood trans fatty acid levels and risk of prostate cancer". Proc. Amer. Assoc. Cancer Res. 47 (1): 943. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- PMID 21518693.

- ^ "Breast cancer: a role for trans fatty acids?". World Health Organization (Press release). 11 April 2008. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008.

- PMID 18390841.

- .

- PMID 11508264.

- PMID 11874924.

- ^ Gosline A (12 June 2006). "Why fast foods are bad, even in moderation". New Scientist. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ "Six years of fast-food fats supersizes monkeys". New Scientist (2556): 21. 17 June 2006.

- ^ S2CID 4835948.

- ^ Thompson TG. "Trans Fat Press Conference". Archived from the original on 9 July 2006., US Secretary of health and human services

- PMID 17209201.

- ^ Roan S (28 January 2011). "Trans fats and saturated fats could contribute to depression". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- S2CID 32898004.

- PMID 22403632.

- PMID 26083739.

- PMID 26203267.

- PMID 15043986.

- ^ Landis CR, Weinhold F. Origin of trans-bent geometries in maximally bonded transition metal and main group molecules. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006 Jun 7;128(22):7335-45.

- PMID 15058815.

- PMID 16844601.

- PMID 7345825.

- ^ "National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 28". United States Department of Agriculture.[dead link]

- ^ National Dairy Council (18 June 2004). "comments on 'Docket No. 2003N-0076 Food Labeling: Trans Fatty Acids in Nutrition Labeling'" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-05-16. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- PMID 20209147.

- PMID 15321800.

- S2CID 32082565.

- ^ Trans Fats From Ruminant Animals May Be Beneficial – Health News Archived 2013-01-17 at the Wayback Machine. redOrbit (8 September 2011). Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- PMID 19923390.

- .

- ^ David J. Baer, PhD. US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Laboratory. New Findings on Dairy Trans Fat and Heart Disease Risk, IDF World Dairy Summit 2010, 8–11 November 2010. Auckland, New Zealand

- .

- ^ UK Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (2007). "Update on trans fatty acids and health, Position Statement" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2010.

- PMID 20209147.

- ^ "Trans fat". It's your health. Health Canada. Dec 2007. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012.

- ^ "EFSA sets European dietary reference values for nutrient intakes" (Press release). European Food Safety Authority. 26 March 2010.

- ^ "WHO plan to eliminate industrially-produced trans-fatty acids from global food supply" (Press release). World Health Organization. 14 May 2018.

- ^ Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. i. Archived from the original on 18 September 2006.

- ^ Summary Archived 2007-06-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. 447.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. 424.[permanent dead link]

- PMID 16028984.

- ^ Hadzipetros P (25 January 2007). "Trans Fats Headed for the Exit". CBC News.

- ^ Spencelayh M (9 January 2007). "Trans fat free future". Royal Society of Chemistry.

- S2CID 45576671.

- PMID 27422506.

- (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03

- (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03

- PMID 11248878

- (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03

- (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03

- PMID 8172869

- (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-04

- S2CID 3986807

- (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-04

- S2CID 22276158

- (PDF) from the original on 2007-01-28. Retrieved 2007-01-19.

- PMID 17462099

- (PDF) from the original on 2004-02-14

- ^ "Boston scientists say triglycerides play key role in heart health". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ^

Ivanova EA, Myasoedova VA, Melnichenko AA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN (2017). "Small Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein as Biomarker for Atherosclerotic Diseases". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2017: 1273042. PMID 28572872.

- ^ "Triglycerides". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ^ Crawford, H., Micheal. Current Diagnosis & Treatment Cardiology. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill Medical, 2009. p19

- ^ "What's considered normal?". Triglycerides: Why do they matter?. Mayo Clinic. 28 September 2012.

- ^ a b

Nordestgaard, BG; Varbo, A (August 2014). "Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease". The Lancet. 384 (9943): 626–35. S2CID 33149001.

- PMID 11834142. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ a b Crawford, H., Micheal. Current Diagnosis & Treatment Cardiology. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill Medical, 2009. p21

- ^ a b c

Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. (September 2012). "Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97 (9): 2969–89. PMID 22962670.

- ^

Davidson, Michael H. (28 January 2008). "Pharmacological Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease". In Davidson, Michael H.; Toth, Peter P.; Maki, Kevin C. (eds.). Therapeutic Lipidology. Contemporary Cardiology. Cannon, Christopher P.; Armani, Annemarie M. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press, Inc. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-1-58829-551-4.

- ^

Abourbih S, Filion KB, Joseph L, Schiffrin EL, Rinfret S, Poirier P, Pilote L, Genest J, Eisenberg MJ (2009). "Effect of fibrates on lipid profiles and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review". Am J Med. 122 (10): 962.e1–962.e8. PMID 19698935.

- ^

Jun M, Foote C, Lv J, et al. (2010). "Effects of fibrates on cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 375 (9729): 1875–1884. S2CID 15570639.

- ^

Blair, HA; Dhillon, S (Oct 2014). "Omega-3 carboxylic acids: a review of its use in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia". Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 14 (5): 393–400. S2CID 23706094.

- PMID 24883315.