Federico Borromeo

Milan | |

|---|---|

| Appointed | 24 April 1595 |

| Term ended | 21 September 1631 |

| Predecessor | Gaspare Visconti |

| Successor | Cesare Monti |

| Other post(s) | Cardinal-Priest of Santa Maria degli Angeli |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 11 June 1595 by Clement VIII |

| Created cardinal | 18 December 1587 by Sixtus V |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 August 1564 |

| Died | 21 September 1631 (aged 67) Milan, Duchy of Milan |

| Buried | Milan Cathedral |

| Parents | Giulio Cesare Borromeo Margherita Borromeo |

| Alma mater | University of Pavia |

Federico Borromeo (Italian:

Early life

Federico Borromeo was born in Milan as the second son of Giulio Cesare Borromeo, Count of Arona, and Margherita Trivulzio. The family was influential in both the secular and ecclesiastical spheres and Federico was cousin of Saint Charles Borromeo, the latter previous Archbishop of Milan and a leading figure during the Counter-Reformation.[2]

He studied in

As cardinal, he participated in the papal conclaves of 1590, 1591, 1592, 1605 and 1623 (he was absent from the election of 1621). His attendance in the first conclave of 1590 at the age of 26 made him one of the youngest Cardinals to participate in the election of a pontiff.

In Rome, Federico was not particularly interested in political issues, but he focused on scholarship and prayer. He collaborated on the issuing of the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate and to the publication of the acts of the Council of Trent.[3] He served as the first cardinal protector of his friend Federico Zuccari's Accademia di San Luca.[6]

Archbishop of Milan

On 24 April 1595

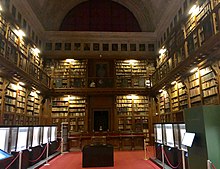

In 1609 he founded the

The Ambrosiana was, after the

A patron of the arts, Federico had the famous

He is most notable for his efforts to feed the poor of Milan during the great

Federico Borromeo took part in eight Papal conclaves. At the papal conclave of August 1623, he received 18 votes but was opposed by the Spanish party.[17] He died in Milan on 21 September 1631 at the age of 67.

Works

Federico Borromeo was a prolific writer, to the extent that he can be considered the most important Milanese writer of the first half of the seventeenth century, alongside Giuseppe Ripamonti.[18] He composed some 71 printed and 46 manuscript books written mostly in Latin that discuss various ecclesiastical issues.[4] His better known works are Meditamenta litteraria (1619), De gratia principum (1625), De suis studiis commentarius (1627), De ecstaticis mulieribus et illusis (1616), De acquirendo contemplationis habitu, De assidua oratione, De naturali ecstasi (1617), De vita Catharinae Senensis monacae conversae (1618 on Suor Caterina Vannini of Siena), Tractatus habiti ad sacras virgines (1620–1623), De cognitionibus quas habent daemones (1624), and De linguis, nominibus et numero angelorum (1628).[3] His writings are listed by Cesare Cantù.[19]

List of works

- Archiepiscopalis fori Sanctae Mediolanensis Ecclesiae taxae (in Latin). Milano: eredi Pacifico Da Ponte. 1624.

- Federico Borromeo (1630). De vita contemplativa, sive de valetudine ascetica libri duo (in Latin). Milano: typographia Collegij Ambrosiani.

- Federico Borromeo (1632). De christianae mentis iucunditate libri tres (in Latin). Milano: typographia Collegij Ambrosiani.

- Federico Borromeo (1632). De sacris nostrorum temporum oratoribus libri quinque (in Latin). Milano: typographia Collegij Ambrosiani.

- Federico Borromeo (1632). De concionante episcopo libri tres (in Latin). Milano: typographia Collegij Ambrosiani.

- Federico Borromeo (1632). Il libro intitulato la gratia de' principi. Milano: Stamperia del Collegio Ambrosiano.

- Federico Borromeo (1632). I tre libri delle laudi divine. Milano: Stamperia del Collegio Ambrosiano.

- Federico Borromeo (1633) [1619]. Meditamenta litteraria (in Latin) (2 ed.). Milano: typographia Collegij Ambrosiani.

- Federico Borromeo (1756) [1618]. I tre libri della vita della venerabile madre suor Caterina Vannini sanese monaca convertita (3 ed.). Padova: Giuseppe Comino.

Legacy

Federico Borromeo appears as a character in Alessandro Manzoni's 1827 novel The Betrothed (I promessi sposi), in which he is characterized as an intelligent humanist and saintly servant of Christ, serving the people of Milan unselfishly during the 1630 plague; in the novel he is called Federigo Borromeo, from the Spanish. In 1865 the citizens of Milan erected a marble statue of him next to the gates of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana.[4] The monument was realized by Costanzo Corti. It stands in Piazza San Sepolcro, in front of the former main façade of Ambrosiana, currently being its back façade. On one side of the pedestal of the statue is the phrase from Manzoni's I Promessi Sposi: "He was one of those men rare in every age, who employed extraordinary intelligence, the resources of an opulent condition, the advantages of privileged stations, and an unflinching will in the search and practice of higher and better things". On the other side are the words: "He conceived the plan of the Ambrosian Library, which he built at great expense, and organized in 1609 with an equal activity and prudence".

While at the service of Federico Borromeo,

The effort to canonize Federico began soon after his death, and documents in support of his case were still being collected in the 1690s, but the process was never institutionalized by Church authorities due to the opposition of the Spanish crown.[21]

References

Notes

- ^ a b David Cheney. "Federico Cardinal Borromeo (Sr.)". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ISBN 88-7030-891-X.

- ^ a b c Prodi 1971.

- ^ a b c Shahan, Thomas (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b Mols 2003, p. 541.

- ^ Jones 1988, p. 261.

- OCLC 53276621.

- ^ D'Amico 2012, p. 113.

- ^ Simar, Théophile (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ISBN 9780191626746.

- ^ Paredi 1983, p. 25.

- ^ In his book De pictura sacra (1624) Borromeo explains that the gallery was intended as a public resource in line with the Council of Trent's call for the faithful to be educated through images as well as words.

- ISBN 9780198206088.

- ISBN 9780297000990.

- ^ "The Colossus of Saint Charles in Arona". ambrosiana.it.

- ^ Findlen, Paula (1994). Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. University of California Press. p. 34.

- ^ Mols 2003, p. 542.

- ^ Zaggia 2014, p. 195.

- ^ La Lombardia nel secolo XVII (Milan 1832, appendix D).

- ISBN 978-1135042929.

- ^ D'Amico 2012, p. 115.

Bibliography

- Rivola, Francesco (1656). Vita di Federico Borromeo. Milan: per Dionisio Gariboldi.

- Bosca, Pietro Paolo (1723). De origine et statu bibliothecæ Ambrosianæ libri V. in quibus de bibliothecæ conditore, conservatoribus et collegii Ambrosiani doctoribus, ut de illustribus pictoribus, aliisque artificibus, et denique de reditibus ejusdem bibliothecæ agitur. Lugduni Batavorum: .

- Bascapè, Carlo(1836). "De Federico archiepiscopo et cardinale". Documenti Spettanti Alla Storia della Chiesa Milanese. Como: 43–111.

- Maiocchi, Roberto; Moiraghi, Attilio (1916). Federico Borromeo studente e gli inizi del collegio. Pavia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gabrieli, Giuseppe (1933–1934). "Federico Borromeo a Roma". Archivio della Società romana di storia patria. LVI–LVII: 157–217.

- Coppa, Simonetta (1970). "Federico Borromeo Teorico d'arte: Annotazioni in margine al "De pictura sacra" ed al "Museum"". Arte Lombarda. 15 (1): 65–70. JSTOR 43105602.

- Prodi, Paolo (1971). "Borromeo, Federico". ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- Paredi, Angelo (1983). A History of the Ambrosiana. Medieval Institute, University of Notre Dame. ISBN 9780268010782.

- Jones, Pamela M. (1988). "Federico Borromeo as a Patron of Landscapes and Still Lifes: Christian Optimism in Italy ca. 1600". JSTOR 3051119.

- Agosti, Barbara (1992). "Federico Borromeo, le antichità cristiane e i primitivi". Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia. III. 22 (2): 481–493. JSTOR 24307845.

- Pelizzoni, Stefano (1995). "Federico Borromeo e le note di lettura del periodo romano". Aevum. 69 (3): 641–664. JSTOR 20860553.

- Jones, Pamela M. (1997). Federico Borromeo e l'Ambrosiana: arte e riforma cattolica nel XVII secolo a Milano. Vita e Pensiero. ISBN 9788834326695.

- Ferro, Roberta (2001). "Gli scritti di Federico Borromeo sul metodo degli studi". Aevum. 75 (3): 737–758. JSTOR 20861249.

- Martini, Alessandro (2002). Burgio, Santo; Ceriotti, Luca (eds.). "La formazione umanistica di Federico Borromeo tra letteratura latina e volgare". Studia Borromaica. 16: 197–214.

- Diffley, Paul (2002). "Borromeo, Federico". The Oxford Companion to Italian Literature. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- Giombi, Samuele (2005). "Federico Borromeo, vescovo e uomo di cultura". Rivista di storia della Chiesa in Italia. 59 (1): 143–149. JSTOR 43050216.

- Pasini, Cesare (2005). "Le acquisizioni librarie del cardinale Federico Borromeo e il nascere dell'Ambrosiana". Studia Borromaica. 19: 461–490.

- Negruzzo, Simona (2012). "L'educazione intellettuale secondo Federico Borromeo". La formazione delle élites in Europa dal Rinascimento alla Restaurazione. Atti del Convegno internazionale. Foggia 31 marzo - 1º aprile 2011. Rome: Aracne: 115–132.

- D'Amico, Stefano (2012). Spanish Milan. A City Within the Empire, 1535-1706. ISBN 9781137309372.

- Franzosini, Edgardo (2013). Sotto il nome del Cardinale. Milan: Adelphi. ISBN 9788845927751.

- Tom Devonshire Jones; Linda Murray; Peter Murray, eds. (2013). "Borromeo, Saint, Charles, and Cardinal Federigo". The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art and Architecture (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 66–67. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

External links

- Zaggia, Massimo (2014). "Culture in Lombardy, ca. 1535–1706". A Companion to Late Medieval and Early Modern Milan: 190–213. ISBN 9789004284128.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Shahan, Thomas Joseph (1913). "Federico Borromeo". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Shahan, Thomas Joseph (1913). "Federico Borromeo". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: McMahon, Joseph H. (1913). "Ambrosian Library". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: McMahon, Joseph H. (1913). "Ambrosian Library". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Mols, R. (2003). "Borromeo, Federigo". In Thomas Carson; Joann Cerrito (eds.). Thomson Gale. pp. 541–42.