Ethnic groups in the Philippines

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

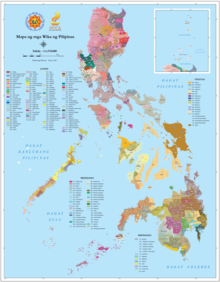

The Philippines is inhabited by more than 182 ethnolinguistic groups,[1]: 5 many of which are classified as "Indigenous Peoples" under the country's Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997. Traditionally-Muslim peoples from the southernmost island group of Mindanao are usually categorized together as Moro peoples, whether they are classified as Indigenous peoples or not. About 142 are classified as non-Muslim Indigenous people groups, and about 19 ethnolinguistic groups are classified as neither Indigenous nor Moro.[1]: 6 Various migrant groups have also had a significant presence throughout the country's history.

The

About 142 of

About 86 to 87 percent of the Philippine population belong to the 19 ethnolinguistic groups are classified as neither Indigenous nor Moro.[1]: 6 These groups are sometimes collectively referred to as "Lowland Christianized groups," to distinguish them from the other ethnolinguistic groups.[10] The most populous of these groups, with populations exceeding a million individuals, are the Ilocano, the Pangasinense, the Kapampangan, the Tagalog, the Bicolano, and the Visayans (including the Cebuano, the Boholano, the Hiligaynon/Ilonggo, and the Waray).[1]: 16 Many of these groups converted to Christianity,[citation needed] particularly both the native and migrant lowland-coastal groups,[11] and adopted foreign elements of culture throughout the country's history.[citation needed]

Due to the past history of the Philippines since the

Aside from migrant groups which speak their own languages, most Filipinos speak languages classified under the

Origins

There are several opposing theories regarding the origins of ancient Filipinos, starting with the "Waves of Migration" hypothesis of H. Otley Beyer in 1948, which claimed that Filipinos were "Indonesians" and "Malays" who migrated to the islands. This is completely rejected by modern anthropologists and is not supported by any evidence, but the hypothesis is still widely taught in Filipino elementary and public schools resulting in the widespread misconception by Filipinos that they are "Malays".[23][24]

The most widely accepted theory, however, is the

Prehistoric

The Negritos arrived about 30,000 years ago and occupied several scattered areas throughout the islands. Recent archaeological evidence described by Peter Bellwood claimed that the ancestors of Filipinos, Malaysians, and Indonesians first crossed the Taiwan Strait during the Prehistoric period. These early mariners are thought to be the Austronesian people. They used boats to cross the oceans, and settled into many regions of Southeast Asia, the Polynesian Islands, and Madagascar.[citation needed]

Two early East Asian waves (

The first Austronesians reached the Philippines at around 2200 BC, settling the

By the 16th century,

| Location | 1603 | 1636 | 1642 | 1644 | 1654 | 1655 | 1670 | 1672 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manila[38] | 900 | 446 | — | 407 | 821 | 799 | 708 | 667 |

| Fort Santiago[38] | — | 22 | — | — | 50 | — | 86 | 81 |

| Cavite[38] | — | 70 | — | — | 89 | — | 225 | 211 |

| Cagayan[38] | 46 | 80 | — | — | — | — | 155 | 155 |

Calamianes[38]

|

— | — | — | — | — | — | 73 | 73 |

| Caraga[38] | — | 45 | — | — | — | — | 81 | 81 |

| Cebu[38] | 86 | 50 | — | — | — | — | 135 | 135 |

| Formosa[38] | — | 180 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Moluccas[38]

|

80 | 480 | 507 | — | 389 | — | — | — |

| Otón[38] | 66 | 50 | — | — | — | — | 169 | 169 |

| Zamboanga[38] | — | 210 | — | — | 184 | — | — | — |

| Other[38] | 255 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| [38] | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Total Reinforcements[38] | 1,533 | 1,633 | 2,067 | 2,085 | n/a | n/a | 1,632 | 1,572 |

Another 35,000 Mexican immigrants arrived in the 1700s[40][39] and they were part of a Philippine population of 1.2 Million, forming about 2.91% of the population.

In the late 1700s to early 1800s, Joaquín Martínez de Zúñiga, an Agustinian Friar, in his Two Volume Book: "Estadismo de las islas Filipinas"[41][42] compiled a census of the Spanish-Philippines based on the tribute counts (Which represented an average family of seven to ten children[43] and two parents, per tribute)[44] and came upon the following statistics:

| Province | Native Tributes | Spanish Mestizo Tributes | All Tributes[a] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tondo[41]: 539 | 14,437-1/2 | 3,528 | 27,897-7 |

| Cavite[41]: 539 | 5,724-1/2 | 859 | 9,132-4 |

| Laguna[41]: 539 | 14,392-1/2 | 336 | 19,448-6 |

| Batangas[41]: 539 | 15,014 | 451 | 21,579-7 |

| Mindoro[41]: 539 | 3,165 | 3-1/2 | 4,000-8 |

| Bulacan[41]: 539 | 16,586-1/2 | 2,007 | 25,760-5 |

| Pampanga[41]: 539 | 16,604-1/2 | 2,641 | 27,358-1 |

| Bataan[41]: 539 | 3,082 | 619 | 5,433 |

| Zambales[41]: 539 | 1,136 | 73 | 4,389 |

Ilocos[42] : 31

|

44,852-1/2 | 631 | 68,856 |

| Pangasinan[42]: 31 | 19,836 | 719-1/2 | 25,366 |

| Cagayan[42]: 31 | 9,888 | 0 | 11,244-6 |

Camarines[42] : 54

|

19,686-1/2 | 154-1/2 | 24,994 |

| Albay[42]: 54 | 12,339 | 146 | 16,093 |

| Tayabas[42]: 54 | 7,396 | 12 | 9,228 |

| Cebu[42]: 113 | 28,112-1/2 | 625 | 28,863 |

| Samar[42]: 113 | 3,042 | 103 | 4,060 |

| Leyte[42]: 113 | 7,678 | 37-1/2 | 10,011 |

| Caraga[42]: 113 | 3,497 | 0 | 4,977 |

| Misamis[42]: 113 | 1,278 | 0 | 1,674 |

Negros Island[42] : 113

|

5,741 | 0 | 7,176 |

| Iloilo[42]: 113 | 29,723 | 166 | 37,760 |

| Capiz[42]: 113 | 11,459 | 89 | 14,867 |

| Antique[42]: 113 | 9,228 | 0 | 11,620 |

Calamianes[42] : 113

|

2,289 | 0 | 3,161 |

| TOTAL | 299,049 | 13,201 | 424,992-16 |

The Spanish-Filipino population as a proportion of the provinces widely varied; with as high as 19% of the population of Tondo province [41]: 539 (The most populous province and former name of Manila), to Pampanga 13.7%,[41]: 539 Cavite at 13%,[41]: 539 Laguna 2.28%,[41]: 539 Batangas 3%,[41]: 539 Bulacan 10.79%,[41]: 539 Bataan 16.72%,[41]: 539 Ilocos 1.38%,[42]: 31 Pangasinan 3.49%,[42]: 31 Albay 1.16%,[42]: 54 Cebu 2.17%,[42]: 113 Samar 3.27%,[42]: 113 Iloilo 1%,

The current modern-day Chinese Filipinos are mostly the descendants of immigrants from

There are also

The Philippines was a

Practicing

In 2013, according to the Senate of the Philippines, there were approximately 1.35 million ethnic (or pure) Chinese within the Philippine population, while Filipinos with any Chinese descent comprised 22.8 million of the population.[12]

Genetics

The results of a massive DNA study conducted by the

Moro ethnolinguistic groups

The collective term

Molbog

The Molbog (referred to in the literature as Molebugan or Molebuganon) are concentrated in southern Palawan, around Balabac, Bataraza, and are also found in other islands of the coast of Palawan as far north as Panakan. They are the only indigenous people in Palawan where the majority of its people are Muslims. The area constitutes the homeland of the Molbog people since the classical era prior to Spanish colonization. The Molbog are known to have a strong connection with the natural world, especially with the sacred pilandok (Philippine mouse-deer), which can only be found in the Balabac islands. The coconut is especially important in Molbog culture at it is their most prized agricultural crop. The word Malubog means "murky or turbid water". The Molbog are likely a migrant people from nearby Sabah, North Borneo. Based on their dialect and some socio-cultural practices, they seem to be related to the Orang Tidung or Tirum (Camucone in Spanish), an Islamized ethnolinguistic group native to the lower east coast of Sabah and upper East Kalimantan. They speak the Molbog language, which is related to Bonggi, spoken in Sabah, Malaysia. However, some Sama words (of the Jama Mapun variant) and Tausug words are found in the Molbog dialect after a long period of exposure with those ethnics. This plus a few characteristics of their socio-cultural life style distinguish them from the Orang Tidung. Molbog livelihood includes subsistence farming, fishing and occasional barter trading with the Moros and neighbouring ethnolinguistic groups in Sabah. In the past, both the Molbog and the Palawanon Muslims were ruled by Sulu datus, thus forming the outer political periphery of the Sulu Sultanate. Intermarriage between Tausug and the Molbog hastened the Islamization of the Molbog. The offsprings of these intermarriages are known as kolibugan or "half-breed".

Kolibugan Subanon

The

Maranao

The

Iranun/Ilanun

The

Maguindanaon

The

Sangil/Sangirese

The

because of its proximity to Indonesia; they speak Cebuano & Tagalog as second languages & are Protestant Christians by faith.Yakan

The

Tausug

The

Jama Mapun

The

Banguingui

Sama Dea (Samal/Sama)

The

Sama Bihing/Sama Lipid

The

Sama Dilaut (Bajau)

The

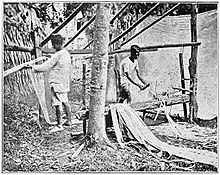

Non-Moro indigenous peoples

There are more than 100 highland, lowland, and coastland indigenous groups in the Philippines. These include:

Igorot

The

Isnag

The

Tinguian/Itneg

The

Kalinga

The

Balangao

The

Bontoc

The Bontoc live on the banks of the Chico River in the Central Mountain Province on the island of Luzon. They speak Bontoc and Ilocano. They formerly practiced head-hunting and had distinctive body tattoos. Present-day Bontocs are a peaceful agricultural people who have, by choice, retained most of their traditional culture despite frequent contacts with other groups. The Bontoc social structure used to be centered around village wards (ato) containing about 14 to 50 homes. Traditionally, young men and women lived in dormitories and ate meals with their families. This gradually changed with the advent of Christianity. In general, however, it can be said that all Bontocs are very aware of their own way of life and are not overly eager to change.

Ifugao

The

Kankanaey

The Kankanaey domain includes Western Mountain Province, northern Benguet and southeastern Ilocos Sur. Like most Igorot ethnic groups, the Kankanaey built sloping terraces to maximize farm space in the rugged terrain of the Cordilleras. They speak the Kankanaey language. The only difference amongst the Kankanaey are the way they speak such as intonation and word usage. In intonation, there is distinction between those who speak Hard Kankanaey (Applai) and Soft Kankanaey. Speakers of Hard Kankanaey are from the towns of Sagada and Besao in the western Mountain Province as well as their environs. They speak Kankanaey with a hard intonation where they differ in some words from the soft-speaking Kankanaey. Soft-speaking Kankanaey come from Northern and other parts of Benguet, and from the municipalities of Sabangan, Tadian and Bauko in Mountain Province. They also differ in their ways of life and sometimes in culture.

Kalanguya

The

Karao

The

Iwak

The Iwak people (Oak, Iguat, Iwaak, etc.) is a small ethnic group, which has a population of approximately 3,000, dispersed in small fenced-in villages which are usually enclaves in communities of surrounding major ethnic groups like the Ibaloy and Ikalahan. The characteristic village enclosing fences are sometimes composed in part of the houses with the front entry facing inward. Pig sties are part of the residential architecture. The Iwak are found principally in the municipalities of Boyasyas and Kayapa, province of Nueva Vizcaya. The subgroups are: (1) Lallang ni I’Wak, (2) Ibomanggi, (3) Italiti, (4) Alagot, (5) Itangdalan, (6) Ialsas, (7) Iliaban, (8)Yumanggi, (9) Ayahas, and (10) Idangatan.[66] They speak the Iwaak language, which is a Pangasinic language which makes it closely related to Pangasinense.

Isinai

The

Ibaloi

The Ibaloi (Ibaloi: ivadoy, /ivaˈdoj/) are an indigenous ethnic group found in Benguet Province of the northern Philippines. The native language is Ibaloi, also known as Inibaloi or Nabaloi. Ibaloi is derived from i-, a prefix signifying "pertaining to" and badoy or house, together then meaning "people who live in houses". The Ibaloi (also Ibaloy and Nabaloi) and Kalanguya (also Kallahan and Ikalahan) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Philippines who live mostly in the southern part of Benguet, located in the Cordillera of northern Luzon, and Nueva Vizcaya in the Cagayan Valley region. They were traditionally an agrarian society. Many of the Ibaloi and Kalanguya people continue with their agriculture and rice cultivation. The Ibaloi language is closely related to the Pangasinan language, primarily spoken in the province of Pangasinan, located southwest of Benguet.

Ilongot

The

Mangyan

Mangyan is the generic name for the eight indigenous groups found on the island of Mindoro, southwest of the island of Luzon in the Philippines, each with its own tribal name, language, and customs. They occupy nearly the whole of the interior of the island of Mindoro. The total population may be around 280,000, but official statistics are difficult to determine under the conditions of remote areas, reclusive tribal groups and some having little if any outside world contact. They also speak Tagalog as their second language because of arrival of Tagalog settlers from Batangas.[68]

Iraya

The Iraya are Mangyans that live in municipalities in northern Mindoro, such as Paluan, Abra de Ilog, northern Mamburao, and Santa Cruz municipalities in Occidental Mindoro, and Puerto Galera and San Teodoro municipalities in Oriental Mindoro. They have also been found in Calamintao, on the northeastern boundary of Santa Cruz municipality (7 km up the Pagbahan River from the provincial highway). They speak the Iraya language which is part of the North Mangyan group of Malayo-Polynesian languages, though it shows considerable differences to Tadyawan and Alangan, the other languages in this group. There are 6,000 to 8,000 Iraya speakers, and that number is growing. The language status of Iraya is developing, meaning that this language is being put to use in a strong and healthy manner by its speakers, and it also has its own writing system (though not yet completely common nor maintainable).

Alangan

The

Tadyawan

Tawbuid

The Tau-build (or Tawbuid) Mangyans live in central Mindoro. They speak the Tawbuid language, which is divided into eastern and western dialects. The Bangon Mangyans also speak the western dialect of Tawbuid. In Oriental Mindoro, Eastern Tawbuid (also known as Bangon) is spoken by 1,130 people in the municipalities of Socorro, Pinamalayan, and Gloria.

In Occidental Mindoro, Western Tawbuid (also known as Batangan) is spoken by 6,810 people in the municipalities of Sablayan and Calintaan.

Bangon

The Mangyan group known on the east of Mindoro as Bangon may be a subgroup of Tawbuid, as they speak the 'western' dialect of that language. They also have a kind of poetry which is called the Ambahan.

Buhid

The

Hanunoo

Ratagnon

Ratagnon (also transliterated Datagnon or Latagnon) are mangyans of the southernmost tip of Occidental Mindoro in the Mindoro Islands along the Sulu Sea. They live in the southernmost part of the municipality of Magsaysay in Occidental Mindoro. The Ratagnon language is similar to the Visayan Cuyunon language, spoken by the inhabitants of Cuyo Island in Northern Palawan. The Ratagnon women wear a wrap-around cotton cloth from the waistline to the knees and some of the males still wear the traditional g-string. The women's breast covering is made of woven nito (vine). They also wear accessories made of beads and copper wire. The males wear a jacket with simple embroidery during gala festivities and carry flint, tinder, and other paraphernalia for making fire. Both sexes wear coils of red-dyed rattan at the waistline. Like other Mangyan tribes, they also carry betel chew and its ingredients in bamboo containers. Today only around 2 to 5 people speak the Ratagnon language, which is nearly extinct, out of an ethnic population of 2,000 people, since speakers are shifting to Tagalog. They appear to also have intermarried with lowlanders.

Tribal Palaweño

The indigenous peoples of Palawan are a diverse group of both indigenous tribes and lowland groups that historically migrated to the island of Palawan and its outlying islands. These ethnolinguistic groups are widely distributed to the long strip of mainland island literally traversing Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. Listed below are specifically the tribal groups of Palawan, as opposed to its urban lowland groups that historically settled its cities and towns. Palawan is home to many indigenous peoples whose origins date back thousands of centuries. Pre-historic discoveries reveal how abundant cultural life in Palawan survived before foreign occupiers and colonizers reached the Philippine archipelago. Today, Palawan is making its best to preserve and conserve the richness of its cultural groups. The provincial government strives to support the groups of indigenous peoples of Palawan.

Tagbanwa

The

Palawano

The

Taaw't Bato

The

Suludnon

The Suludnon are highland

.Suludnon/Sulod/Tumandok

The

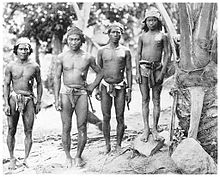

Negrito

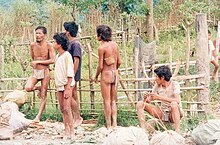

The Negrito are several Australo-Melanesian groups who inhabit isolated parts of Southeast Asia.[70] They all live in remote areas throughout the islands in the Philippines.

Aeta/Agta

The

Batak

The

.Ati

The

Mamanwa

The

Lumad

The

Subanon

As the name implies, these people originally lived along riverbanks in the lowlands, however due to disturbances and competitions from related groups such as the

Mamanwa

The

Manobo/Banobo

The

Higaonon

The

Bukidnon

The

The Bukidnon Lumad is distinct and should not be confused with a few indigenous peoples scattered in the Visayas area who are also alternatively called Bukidnon.

Talaandig

Umayamnon

The

Tigwahonon

The

Matigsalug

The

Manguwangan

The

Kamayo

The

Kalagan

The

Mansaka

The term "

Mandaya

"

Giangan

The

Tagabawa

Tagabawa or Bagobo-Tagabawa are an indigenous tribe in Mindanao. They speak the Tagabawa language, which is a Manobo language, and live in Cotabato, Davao del Sur, and in the surrounding areas of Mt. Apo by Davao City. They have a culture of high respect towards Philippine eagles, known in their language as banog.

Teduray

The

Tagakaulo

Tasaday

The

B'laan

The

The tribe practices indigenous rituals while adapting to the way of life of modern Filipinos. Some also speak

T'boli

The

Sangil

The

Other ethnolinguistic groups

About 86 to 87 percent of the Philippine population belong to the ethnolinguistic groups are classified as neither indigenous nor Moro.[1]: 6 These groups are sometimes collectively referred to as "Lowland Christianized groups", to distinguish them from indigenous ("upland") groups and Moro peoples.[10]

Groups in mainland Luzon

Ivatan

The

, & also Ilocano as second language.Ilocano

The

Bago

The Bago (Bago Igorot) were identified first in the municipality of Pugo in the southeastern side of La Union. This is a highly acculturated group whose villages are along major transportation routes between the lowlands and the Abatan, Benguet markets in the highland. The major ritual practices and beliefs are somewhat related to the northern Kankanay, thus the idea that the people were migrants because of trade from western Mountain Province. The Kankanay regard them as such and not as a specific ethnic group. The language is a mixture of northern Kankanay with an infusion of lowland dialects. Most of the individuals are bilingual with Ilocano as the trade language. Their agricultural activities revolve around a mixture of highland root crops like sweet potatoes, yams, and taro, and lowland vegetables and fruits.[80]

Ibanag

The

Itawes/Itawis/Itawit

The Itawes/Itawis/Itawit are among the earliest inhabitants of the Cagayan Valley in northern Luzon. Their name is derived from the Itawes prefix i- meaning "people of" and tawid or "across the river". As well as their own Itawis language, they speak Ibanag and Ilocano. The contemporary Itawes are charming, friendly, and sociable. They are not very different from other lowland Christianized Filipino ethnic groups in terms of livelihood, housing, and traditions. Their traditional dresses are colorful with red being the dominant color. Farming is a leading source of livelihood. The average families are education-conscious.

Malaweg

The Malaweg are located in sections of Cagayan Valley and Kalinga-Apayao provinces and in the town of Rizal. Their main crops are lowland rice and corn. Tobacco was raised as a cash crop on a foothill west of Piat on the Matalag river near the southeast border of Kalinga-Apayao province, drawing Ibanags from the east. Culturally, they are similar to the neighbor groups: Ibanag and Itawis. Linguistically, they speak a dialect of Itawis.[81]

Gaddang

The

Ga'dang

The

Yogad

The

Bolinao

The

Pangasinan

The Pangasinense people are the eighth-largest ethnolinguistic group in the Philippines. They predominate in the northwestern portion of Central Luzon (central and east Pangasinan, northern Tarlac, northern Nueva Ecija and northern Zambales), as well as southern parts of La Union and Benguet. They are predominantly Christian (mainly Roman Catholic). They primarily use the Pangasinan language, which is spoken by more than 1.2 million individuals, & mostly speak Ilocano as second language.

Sambal

The

Kapampangan

The

Kasiguranin

The Kasiguranin live in Casiguran in Aurora Province. The Kasiguranin language descends from an early Tagalog dialect that had borrowed heavily from Northeastern Luzon Agta languages such as Paranan, and Filipino migrant languages like Ilocano, Visayan languages, Bikol languages, and Kapampangan. It is 82% mutually intelligible with Paranan, a language in eastern Isabela, since Aurora and Isabela lie in close proximity. Kasiguranin speak Ilocano & Tagalog as additional languages. They rely mainly on fishing and farming, as do other groups in Casiguran.[86]

Paranan

The Paranan or Palanan are a group that is largely concentrated on the Pacific side of the province of Isabela about Palanan Bay. The population areas are in Palanan (9,933) with a total population of some 10,925 (NSO 1980). This is probably the northeasternmost extension of the Tagalog language. There is, however, a considerable mixture with the culture of the Negrito from the Paranan Agta language.[87] Paranan speak Ilocano & Tagalog as additional languages.

Tagalog

The Tagalogs are the most widespread ethnic group in the Philippines. They predominate the entirety of the Manila and mainland southern Luzon regions, with a plurality in Central Luzon (mainly in its southeastern portion [Nueva Ecija, Aurora, and Bulacan], as well as parts of Zambales and Bataan provinces except Pampanga and Tarlac), the entirety of Marinduque and coastal parts of Mindoro.[88][89][68] The Tagalog language was chosen as an official language of the Philippines in 1935. Today, Filipino, a de facto version of Tagalog, is taught throughout the archipelago.[90] As of the 2019 census[update], there were about 22.5 million speakers of Tagalog in the Philippines, 23.8 million worldwide.[91] Tagalogs even speak other languages within the environment of other ethnic groups in areas they settled and grew up in, like Ilocano, Pangasinan, and Kapampangan (in Central Luzon).

Caviteño

Ternateño

The

Bicolano

The

Masbateño

Groups in the Mimaropa Region

Lowland Christianized groups of the region of Mimaropa, consisting of the islands or provinces of Mindoro, Marinduque, Romblon, Palawan, and other surrounding islands. They also speak Tagalog as their second language because of arrival of Tagalog settlers from South Luzon.[68]

Bantoanon

The

Inonhan

The

Romblomanon

The

Mangyan

Mangyan is the generic name for the eight indigenous groups found on the island of Mindoro, southwest of the island of Luzon in the Philippines, each with its own tribal name, language, and customs. They occupy nearly the whole of the interior of the island of Mindoro. The total population may be around 280,000, but official statistics are difficult to determine under the conditions of remote areas, reclusive tribal groups and some having little if any outside world contact. They also speak Tagalog as their second language because of arrival of Tagalog settlers from Batangas.[68]

Iraya

The Iraya are Mangyans that live in municipalities in northern Mindoro, such as Paluan, Abra de Ilog, northern Mamburao, and Santa Cruz municipalities in Occidental Mindoro, and Puerto Galera and San Teodoro municipalities in Oriental Mindoro. They have also been found in Calamintao, on the northeastern boundary of Santa Cruz municipality (7 km up the Pagbahan River from the provincial highway). They speak the Iraya language which is part of the North Mangyan group of Malayo-Polynesian languages, though it shows considerable differences to Tadyawan and Alangan, the other languages in this group. There are 6,000 to 8,000 Iraya speakers, and that number is growing. The language status of Iraya is developing, meaning that this language is being put to use in a strong and healthy manner by its speakers, and it also has its own writing system (though not yet completely common nor maintainable).

Alangan

The

Tadyawan

Tawbuid

The Tau-build (or Tawbuid) Mangyans live in central Mindoro. They speak the Tawbuid language, which is divided into eastern and western dialects. The Bangon Mangyans also speak the western dialect of Tawbuid. In Oriental Mindoro, Eastern Tawbuid (also known as Bangon) is spoken by 1,130 people in the municipalities of Socorro, Pinamalayan, and Gloria.

In Occidental Mindoro, Western Tawbuid (also known as Batangan) is spoken by 6,810 people in the municipalities of Sablayan and Calintaan.

Bangon

The Mangyan group known on the east of Mindoro as Bangon may be a subgroup of Tawbuid, as they speak the 'western' dialect of that language. They also have a kind of poetry which is called the Ambahan.

Buhid

The

Hanunoo

Ratagnon

Ratagnon (also transliterated Datagnon or Latagnon) are mangyans of the southernmost tip of Occidental Mindoro in the Mindoro Islands along the Sulu Sea. They live in the southernmost part of the municipality of Magsaysay in Occidental Mindoro. The Ratagnon language is similar to the Visayan Cuyunon language, spoken by the inhabitants of Cuyo Island in Northern Palawan. The Ratagnon women wear a wrap-around cotton cloth from the waistline to the knees and some of the males still wear the traditional g-string. The women's breast covering is made of woven nito (vine). They also wear accessories made of beads and copper wire. The males wear a jacket with simple embroidery during gala festivities and carry flint, tinder, and other paraphernalia for making fire. Both sexes wear coils of red-dyed rattan at the waistline. Like other Mangyan tribes, they also carry betel chew and its ingredients in bamboo containers. Today only around 2 to 5 people speak the Ratagnon language, which is nearly extinct, out of an ethnic population of 2,000 people, since speakers are shifting to Tagalog. They appear to also have intermarried with lowlanders.

Tribal Palaweño

The indigenous peoples of Palawan are a diverse group of both indigenous tribes and lowland groups that historically migrated to the island of Palawan and its outlying islands. These ethnolinguistic groups are widely distributed to the long strip of mainland island literally traversing Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. Listed below are specifically the tribal groups of Palawan, as opposed to its urban lowland groups that historically settled its cities and towns. Palawan is home to many indigenous peoples whose origins date back thousands of centuries. Pre-historic discoveries reveal how abundant cultural life in Palawan survived before foreign occupiers and colonizers reached the Philippine archipelago. Today, Palawan is making its best to preserve and conserve the richness of its cultural groups. The provincial government strives to support the groups of indigenous peoples of Palawan.

Agutaynon

Kagayanen

The

Cuyunon

Tagbanwa

The

Palawano

The

Taaw't Bato

The

Groups in the Visayas

Lowland

Abaknon

The

Waray

The

Caluyanon

The Caluyanon people are found on the Caluya Islands of Antique Province in the Western Visayas Region. They speak the Caluyanon language, but many speakers use either Kiniray-a or Hiligaynon as their second language. According to a recent survey, around 30,000 people speak Caluyanon.[98]

Aklanon

Capiznon

The

Karay-a

The

Hiligaynon

The

Magahat

The

Porohanon

Cebuano

The

Boholano

The

Eskaya

The

Groups in Mindanao

Lowland Christianized groups of the island of Mindanao.

Surigaonon

Kamiguin

The Kamiguin/Kamigin people inhabit the oldest town of the island of Camiguin—Guinsiliban—just off the northern coast of Mindanao. They spoke the Kamigin/Kinamigin language (Quinamiguin, Camiguinon) that is derived from Manobo with an admixture of Boholano. Sagay is the only other municipality where this is spoken. The total population is 531 (NSO 1990). Boholano predominates in the rest of the island. The culture of the Kamiguin has been subsumed within the context of Boholano or Visayan culture. The people were Christianized as early as 1596. The major agricultural products are abaca, cacao, coffee, banana, rice, corn, and coconut. The production of hemp is the major industry of the people since abaca thrives very well in the volcanic soil of the island. The plant was introduced in Bagacay, a northern town of Mindanao, but it is no longer planted there. Small-scale trade carried out with adjoining islands like Cebu, Bohol, and Mindanao.[100] Nowadays, the language is declining as most inhabitants have shifted to Cebuano.

Butuanon

The

Zamboangueño

The

Cotabateño

Davaoeño

Immigrants & mixed peoples

The

Across the

Historical foreign migrants and intermixed peoples

These groups are the historical foreign migrant peoples and the intermixed peoples they produced with native groups, especially the native urban lowland peoples of the Philippines. Those listed below are those groups in modern times that still have some number of Filipinos claiming identity with such background.

Spanish Filipino

Chinese Filipino

Mestizo de Español (Spanish Mestizo)

These are the mixed descendants of the native peoples of the Philippines with the

Mestizo de Sangley (Chinese Mestizo)

Tornatrás (Spanish-Chinese Mestizo)

American Filipino/Filipino American

American (Amerikano/Kano) settlement in the Philippines began during the

Filipinos with Arab ancestry

Indian Filipino/Mestizo de Bombay (Indian Mestizo)

The Philippines has had historical connections with

Japanese Filipino

Japanese people have been settling in the Philippines for centuries even before World War II, therefore there has been much cultural and genetic blending. The Ryukyu Kingdom (located in modern-day Okinawa Prefecture) also had heavy trade and mixing in the Philippines, particularly in Northern Luzon, as depicted in the Boxer Codex.[114][unreliable source][115][failed verification]

Sangil/Sangirese

The

because of its proximity to Indonesia; they speak Cebuano & Tagalog as second languages & are Protestant Christians by faith. The exact population of Sangil people in the Philippines is unknown, but is estimated to be around 10,000 people.Jewish Filipino

As of 2005[update], Filipino Jews numbered at the most 500 people.

Recent modern immigrants and expatriates

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2020) |

These migrant groups are relatively recent immigrants and expatriate groups that mostly immigrated in the modern era, specifically around the 20th century especially from post-

See also

- Demographics of the Philippines

- List of sovereign state leaders in the Philippines

- Indigenous peoples of the Philippines

- Philippine population by country of citizenship

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g Reyes, Cecilia M.; Mina, Christian D.; Asis, Ronina D. (2017). PIDS DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES: Inequality of Opportunities Among Ethnic Groups in the Philippines (PDF) (Report). Philippine Institute for Development Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 8, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ Kamlian, Jamail A. (October 20, 2012). "Who are the Moro people?". Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ Philippines. 2013 Report on International Religious Freedom (Report). United States Department of State. July 28, 2014. SECTION I. RELIGIOUS DEMOGRAPHY. Archived from the original on May 26, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

The 2000 survey states that Islam is the largest minority religion, constituting approximately 5 percent of the population. A 2012 estimate by the National Commission on Muslim Filipinos (NCMF), however, states that there are 10.7 million Muslims, which is approximately 11 percent of the total population.

- ^ "Philippines". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on October 5, 2020. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ S2CID 147472482.

- ^ Moaje, Marita (March 4, 2021). "Drop 'lumad', use ethnic group names instead: NCIP". Philippine News Agency. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ National Statistics Office. “Statistics on Filipino Children.” Journal of Philippine Statistics, vol. 59, no. 4, 2008, p. 119.

- ^ Ulindang, Faina. "Lumad in Mindanao". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ISBN 9781439815519. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via Persée.

- ^ a b Macrohon, Pilar (January 21, 2013). "Senate declares Chinese New Year as special working holiday" (Press release). PRIB, Office of the Senate Secretary, Senate of the Philippines. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021.

- ^ ISBN 9780295800264. Archivedfrom the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ISBN 978-0312234966.

- ISBN 978-1138811072.

- ISBN 9780295800264. Archivedfrom the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ "With a sample population of 105 Filipinos, the company of Applied Biosystems, analysed the Y-DNA of average Filipinos and it is discovered that about 0.95% of the samples have the Y-DNA Haplotype "H1a", which is most common in South Asia and had spread to the Philippines via precolonial Indian missionaries who spread Hinduism". Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ Agnote, Dario (October 11, 2017). "A glimmer of hope for castoffs". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-7007-1286-1. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ Acabado, Stephen; Martin, Marlon; Lauer, Adam J. (2014). "Rethinking history, conserving heritage: archaeology and community engagement in Ifugao, Philippines" (PDF). The SAA Archaeological Record: 13–17. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ Lasco, Gideon (December 28, 2017). "Waves of migration". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on July 22, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ^ ISBN 9780415297776. Archived(PDF) from the original on March 12, 2023. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ISBN 9780521644327.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2004). "Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 24 (The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ PMID 33753512.

- ^ Mijares, Armand Salvador B. (2006). "The Early Austronesian Migration To Luzon: Perspectives From The Peñablanca Cave Sites". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association (26): 72–78. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014.

- ^ Bellwood, Peter (2014). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. p. 213.

- (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ The Cultural Influences of India, China, Arabia, and Japan | Philippine Almanac Archived July 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- from the original on June 3, 2018. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ Stephanie Mawson, ‘Between Loyalty and Disobedience: The Limits of Spanish Domination in the Seventeenth Century Pacific’ (Univ. of Sydney M.Phil. thesis, 2014), appendix 3.

- ^ "Spanish Settlers in the Philippines (1571–1599) By Antonio Garcia-Abasalo" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ The Unlucky Country: The Republic of the Philippines in the 21St Century By Duncan Alexander McKenzie (page xii)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Convicts or Conquistadores? Spanish Soldiers in the Seventeenth-Century Pacific By Stephanie J. Mawson AGI, México, leg. 25, núm. 62; AGI, Filipinas, leg. 8, ramo 3, núm. 50; leg. 10, ramo 1, núm. 6; leg. 22, ramo 1, núm. 1, fos. 408 r –428 v; núm. 21; leg. 32, núm. 30; leg. 285, núm. 1, fos. 30 r –41 v .

- ^ a b Garcia, María Fernanda (1998). "Forzados y reclutas: los criollos novohispanos en Asia (1756-1808)". Bolotin Archivo General de la Nación. 4 (11). Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ Park 2022, p. 100, citing a 1998 journal article.[39]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "ESTADISMO DE LAS ISLAS FILIPINAS TOMO PRIMERO By Joaquín Martínez de Zúñiga (Original Spanish)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y ESTADISMO DE LAS ISLAS FILIPINAS TOMO SEGUNDO By Joaquín Martínez de Zúñiga (Original Spanish)

- ^ "How big were families in the 1700s?" By Keri Rutherford

- ISBN 978-0-8248-6197-1. Archivedfrom the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Maximilian Larena (January 21, 2021). "Supplementary Information for Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years (Page 35)" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. p. 35. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Sangley, Intsik und Sino : die chinesische Haendlerminoritaet in den Philippine. Working paper / Universität Bielefeld, Fakultät für Soziologie, Forschungsschwerpunkt Entwicklungssoziologie, 0936-3408. Universität Bielefeld. 1993. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ "The ethnic Chinese variable in domestic and foreign policies in Malaysia and Indonesia" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 1, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- PMID 26781090. The final component (dark blue in Fig. 3b) has a high frequency in South China (Fig. 2b) and is also seen in Taiwan at ~25–30 %, in the Philippines at ~20–30 % (except in one location which is almost zero) and across Indonesia/Malaysia at 1–10 %, declining overall from Taiwan within Austronesian-speaking populations.

- ^ "Chinese lunar new year might become national holiday in Philippines too". Xinhua News (August 23, 2009). (archived from the original on August 26, 2009)

- ^ Filipino Food and Culture Archived December 31, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Food-links.com. Retrieved on July 4, 2012.

- Indian Dating and Matchmaking in Philippines – Indian Matrimonials Archived October 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Futurescopes.com (January 3, 2011). Retrieved on July 4, 2012.

- Filipino Foods Archived October 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Philippinecountry.com. Retrieved on July 4, 2012.

- Ancient Japanese pottery in Boljoon town |Inquirer News Archived May 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Newsinfo.inquirer.net (May 30, 2011). Retrieved on July 4, 2012.

- Philippines History, Culture, Civilization and Technology, Filipino Archived August 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Asiapacificuniverse.com. Retrieved on July 4, 2012.

- ^ Blair, Emma Helen (1915). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898: Relating to China and the Chinese. Vol. 23. A.H. Clark Company. pp. 85–87. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ISBN 9780429678257.

- ISBN 9780826460745– via Google Books.

- ^ "The Bagelboy Club of the Philippines – History of the Bagelboy Club". www.thebagelboyclub.com. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ Cooper, Matthew (November 15, 2013). "Why the Philippines Is America's Forgotten Colony". National Journal. Archived from the original on February 18, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

c. At the same time, person-to-person contacts are widespread: Some 600,000 Americans live in the Philippines and there are 3 million Filipino-Americans, many of whom are devoting themselves to typhoon relief.

- ^ "200,000–250,000 or More Military Filipino Amerasians Alive Today in Republic of the Philippines according to USA-RP Joint Research Paper Finding" (PDF). Amerasian Research Network, Ltd. (Press release). November 5, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2016.Kutschera, P.C.; Caputi, Marie A. (October 2012). "The Case for Categorization of Military Filipino Amerasians as Diaspora" (PDF). 9TH International Conference On the Philippines, Michigan State University, E. Lansing, MI. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- from the original on February 2, 2022. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

Filipinos appear considerably admixed with respect to the other Asian population samples, carrying on average less Asian ancestry (71%) than our Korean (99%), Japanese (96%), Thai (93%), and Vietnamese (84%) reference samples. We also revealed substructure in our Filipino sample, showing that the patterns of ancestry vary within the Philippines—that is, between the four differently sourced Filipino samples. Mean estimates of Asian (76%) and European (7%) ancestry are greatest for the cemetery sample of forensic signifijicance from Manila.

- from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

[Page 1] ABSTRACT: Filipinos represent a significant contemporary demographic group globally, yet they are underrepresented in the forensic anthropological literature. Given the complex population history of the Philippines, it is important to ensure that traditional methods for assessing the biological profile are appropriate when applied to these peoples. Here we analyze the classification trends of a modern Filipino sample (n = 110) when using the Fordisc 3.1 (FD3) software. We hypothesize that Filipinos represent an admixed population drawn largely from Asian and marginally from European parental gene pools, such that FD3 will classify these individuals morphometrically into reference samples that reflect a range of European admixture, in quantities from small to large. Our results show the greatest classification into Asian reference groups (72.7%), followed by Hispanic (12.7%), Indigenous American (7.3%), African (4.5%), and European (2.7%) groups included in FD3. This general pattern did not change between males and females. Moreover, replacing the raw craniometric values with their shape variables did not significantly alter the trends already observed. These classification trends for Filipino crania provide useful information for casework interpretation in forensic laboratory practice. Our findings can help biological anthropologists to better understand the evolutionary, population historical, and statistical reasons for FD3-generated classifications. The results of our studyindicate that ancestry estimation in forensic anthropology would benefit from population-focused research that gives consideration to histories of colonialism and periods of admixture.

- ^ "Reference Populations – Geno 2.0 Next Generation". Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Peoples of the Philippines: Kolibugan". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. June 17, 2015. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c UNHCR Philippines » Hundreds finally out of legal limbo in groundbreaking pilot between Indonesia, the Philippines, 2016, archived from the original on September 11, 2016, retrieved September 2, 2016

- ^ a b c Indonesians in Mindanao, 2016, retrieved September 2, 2019

- ^ a b c d e f g Maximilian Larena (January 21, 2021). "Supplementary Information for Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years (Page 35)" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. p. 35. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ "IGOROT Ethnic Groups - sagada-igorot.com". Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ "Karao". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Peoples of the Philippines: Iwak". National Commission for the Culture and the Arts. June 17, 2015. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Isinai". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 11, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Lowland Cultural Group of the Tagalogs". Archived from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "Tumandok epic: The Panay indigenous people's struggle for land". politika2013.wordpress.com. October 25, 2011. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- ISBN 0801495830)

- ^ "Subanen History" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-89608-640-1.

- ^ "Manguwangan". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Kamayo". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 11, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Kalagan". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Tiruray". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ a b CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art, Peoples of the Philippines, Ilocano

- ^ "The Filipino Community in Hawaii". University of Hawaii, Center for Philippine studies. Archived from the original on August 9, 2007. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- ^ "Ilocano". Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Archived from the original on January 13, 2011. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- ^ "Peoples of the Philippines: Bago". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. June 17, 2015. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Malaweg". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 9, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Yogad". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Bolinao". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ CCP Encyclopedia or Philippine Art, Peoples of the Philippines, Kapampangan

- ^ Joaquin & Taguiwalo 2004, p. 236.

- ^ "Kasiguranin". Ethnic Groups in the Philippines. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Peoples of the Philippines: Palanan". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. June 17, 2015. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ CCP Encyclopedia or Philippine Art, Peoples of the Philippines, Tagalog

- ^ Joaquin 1999.

- ^ Rubrico, Jessie Grace (1998): The metamorphosis of Filipino as national language Archived November 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, languagelinks.org

- ^ Tagalog at Ethnologue (22nd ed., 2019)

- ^ "Caviteño". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 11, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ (Page 10) Pérez, Marilola (2015). Cavite Chabacano Philippine Creole Spanish: Description and Typology (PDF) (PhD). University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021.

The galleon activities also attracted a great number of Mexican men that arrived from the Mexican Pacific coast as ships' crewmembers (Grant 2009: 230). Mexicans were administrators, priests and soldiers (guachinangos or hombres de pueblo) (Bernal 1964: 188) many though, integrated into the peasant society, even becoming tulisanes 'bandits' who in the late 18th century "infested" Cavite and led peasant revolts (Medina 2002: 66). Meanwhile, in the Spanish garrisons, Spanish was used among administrators and priests. Nonetheless, there is not enough historical information on the social role of these men. In fact some of the few references point to a quick integration into the local society: "los hombres del pueblo, los soldados y marinos, anónimos, olvidados, absorbidos en su totalidad por la población Filipina." (Bernal 1964: 188). In addition to the Manila-Acapulco galleon, a complex commercial maritime system circulated European and Asian commodities including slaves. During the 17th century, Portuguese vessels traded with the ports of Manila and Cavite, even after the prohibition of 1644 (Seijas 2008: 21). Crucially, the commercial activities included the smuggling and trade of slaves: "from the Moluccas, and Malacca, and India… with the monsoon winds" carrying "clove spice, cinnamon, and pepper and black slaves, and Kafir [slaves]" (Antonio de Morga cf Seijas 2008: 21)." Though there is no data on the numbers of slaves in Cavite, the numbers in Manila suggest a significant fraction of the population had been brought in as slaves by the Portuguese vessels. By 1621, slaves in Manila numbered 1,970 out of a population of 6,110. This influx of slaves continued until late in the 17th century; according to contemporary cargo records in 1690, 200 slaves departed from Malacca to Manila (Seijas 2008: 21). Different ethnicities were favored for different labor; Africans were brought to work on the agricultural production, and skilled slaves from India served as caulkers and carpenters.

- ^ "Ternateño". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 11, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ ISBN 9783110134179. Archived(PDF) from the original on September 18, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Lifshey, A. (2012), The Magellan Fallacy: Globalization and the Emergence of Asian and African Literature in Spanish, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press

- ^ "Peoples of the Philippines: Abaknon". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. June 17, 2015. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Caluyanon". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Porohanon". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Peoples of the Philippines: Kamiguin". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. June 17, 2015. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ Jagor, Fëdor, et al. (1870). The Former Philippines thru Foreign Eyes

- ^ "SECOND BOOK OF THE SECOND PART OF THE CONQUESTS OF THE FILIPINAS ISLANDS, AND CHRONICLE OF THE RELIGIOUS OF OUR FATHER, ST. AUGUSTINE" Archived February 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine (Zamboanga City History) "He (Governor Don Sebastían Hurtado de Corcuera) brought a great reënforcements of soldiers, many of them from Perú, as he made his voyage to Acapulco from that kingdom."

- ^ "Cotabateño". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via Persée.

- )

- ISBN 978-1-4068-1542-9. Archivedfrom the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Joaquin & Taguiwalo 2004, p. 42.

- ^ a b Benedict Anderson, ‘Cacique Democracy in the Philippines: Origins and Dreams Archived September 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine’, New Left Review, 169 (May–June 1988)

- ^ a b Gavin Sanson Bagares, Philippine Daily Inquirer, A16 (January 28, 2006)

- ^ Institute for Human Genetics, University of California San Francisco (2015). ""Self-identified East Asian nationalities correlated with genetic clustering, consistent with extensive endogamy. Individuals of mixed East Asian-European genetic ancestry were easily identified; we also observed a modest amount of European genetic ancestry in individuals self-identified as Spanish Filipinos"

- ISBN 978-981-230-799-6. Archivedfrom the original on March 12, 2023. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ^ Mansigh, Lalit. "Chapter 20: Southeast Asia, Table: 20.1" (PDF). Ministry of External Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 19, 2009. Retrieved October 12, 2009.

- ^ "Overseas Indian Population 2001". Little India. Archived from the original on October 20, 2006. Retrieved October 12, 2009.

- ^ Manansala, Paul Kekai (September 5, 2006). "Quests of the Dragon and Bird Clan: Luzon Jars (Glossary)". Archived from the original on January 19, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Ocampo, Ambeth R. "Japanese origins of the Philippine 'halo-halo'". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ Tremml-Werner, Birgit M. (2015). Spain, China, and Japan in Manila, 1571–1644. p. 302. Archived from the original on July 20, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ Villalon, Augusto F. (February 13, 2017). "'Little Tokyo' in Davao". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-135-98723-7.

- ^ "Philippines History, Culture, Civilization and Technology, Filipino". Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2012.

- ^ "A glimmer of hope for castoffs. NGO finding jobs for young, desperate Japanese-Filipinos". The Japan Times. October 11, 2006. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ a b "Philippines Jewish Community". Jewishtimesasia.org. Archived from the original on December 24, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ Schlossberger, E. Cauliflower and Ketchup Archived July 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Scalabrini Migration Center (2013). "Country Migration Report The Philippines 2013" (PDF). iom.int. International Organization for Migration (IOM). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ National Statistics Organization (2010). "Household Population by Country of Citizenship" (PDF). psa.gov.ph. Philippine Statistics Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 16, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

References

- Ooi, Keat Jin (2004). A Historical Encyclopedia From Angkor Wat to East Timor, Vol.1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576077702.

- Joaquin, Nick; Taguiwalo, Beaulah Pedregosa (2004). Culture and history. Anvil Publishing. ISBN 978-971-27-1300-2.

- Agoncillo, Teodoro (1990). History of the Filipino People. Garotech Publishing. ISBN 978-971-8711-06-4.

- Joaquin, Nick (1999). Manila, my Manila. Bookmark. ISBN 978-971-569-313-4.

- "World Factbook : Philippines". CIA. May 9, 2023.

- Park, Paula C. (2022). Intercolonial Intimacies: Relinking Latin/o America to the Philippines, 1898-1964. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-8873-1.

- Kagayanen; by: Jehu P. Cayaon; https://web.archive.org/web/20110819055403/http://kagayanenmovement.webs.com/

External links

- Philippines – Ethnic groups, thecorpusjuris.com, retrieved on 2008-04-06 (See Article XV, Section 3(3))

- Who are the Kagayanens?, Indigenous People Movement

Notes

- ^ Including others such as Latin-Americans and Chinese-Mestizos, pure Chinese paid tribute but were not Philippine citizens as they were transients who returned to China, and Spaniards were exempt