Film Booking Offices of America

Logo from 1926 | |

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Motion pictures |

| Predecessor | Robertson-Cole Corp. |

| Founded | 1922 |

| Defunct | 1929 |

| Fate | Assets transferred to Radio-Keith-Orpheum Corp. |

| Successor | RKO Pictures |

| Headquarters | 1922–1925: 723 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY[1] 1926–1929: 1560 Broadway, New York, NY[2] |

Film Booking Offices of America (FBO), registered as FBO Pictures Corp., was an American film studio of the

The studio, whose core market was America's small towns, also put out many romantic melodramas, action pictures, and comedic

In 1926, Kennedy led an investment group that acquired the company, and he ran it hands-on—traveling frequently to California—with considerable success. Exhibitors cited

Business history

The R-C years

The company that would become FBO began as Robertson-Cole, an importer, exporter, and motion picture distributor with headquarters in London and New York, founded in 1918 by Englishman Harry F. Robertson and American Rufus S. Cole.

In March, the inaugural "convention of the branch managers and field supervisors of the Robertson-Cole Distributing Corporation" was announced.

Rufus Cole also entered into a working relationship with Hallmark investor

A new identity

In 1922, Robertson-Cole underwent a major reorganization as the company's founders departed.

H.C.S. Thomson of Graham's, already chairman of the board, became the business's managing director with the departure of Powers.

As a distributor, Film Booking Offices focused on marketing its films to small-town exhibitors and independent theater chains (that is, those not owned by one of the

Kennedy takes command

While still at the Hayden, Stone investment firm, Kennedy had boasted to a colleague, "Look at that bunch of pants pressers in Hollywood making themselves millionaires. I could take the whole business away from them."

Studio chief Fineman departed around the time of Kennedy's purchase to work at the larger First National Pictures.[49] The new owner hired Edwin King away from Famous Players–Lasky's New York studio to replace him, but took a personal hand in guiding the company creatively as well as financially.[50] His brand, "Joseph P. Kennedy Presents", would proceed to appear on over a hundred films.[51] Kennedy soon brought stability to FBO, making it one of the most reliably profitable outfits in the minor leagues of the Hollywood studio system. The focus was on films with Main Street appeal and minimal costs.[52] "We are trying", he declared, "to be the Woolworth and Ford of the motion picture industry rather than the Tiffany."[53] Some stars were less than pleased with Kennedy's penny-pinching; Evelyn Brent, in particular, was troubled by what she saw as FBO's declining production standards and was granted her release.[54] Westerns remained the studio's backbone, along with various action pictures and romantic scenarios; as Kennedy put it, "Melodrama is our meat."[55] Gene Stratton-Porter, then, was the gravy: according to the 1926 Exhibitors Herald survey, The Keeper of the Bees, for which shooting was completed while the novel was still being serialized in McCall's, was the number one picture in the entire country that year. The remainder of FBO's top five comprised, once again, three Fred Thomson pictures, along with another Stratton-Porter adaptation.[56]

During this period, the average production cost of FBO features was around $50,000, and few were budgeted at anything more than $75,000.[57] By comparison, in 1927–28 the average cost at Fox was $190,000; at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, $275,000.[58] In a broad economization move, in 1927, FBO ended the long-term contracts with writers that were an industry norm, shifting story assignments to a freelance basis.[59] One major expense Kennedy didn't spare: with the powerful United Artists and Paramount studios circling Fred Thomson, Kennedy kept him at FBO for $15,000 a week (assigning the contract to a newly created corporation, Fred Thomson Productions, "for tax purposes"). The actor now had the second-highest straight salary in the entire industry, surpassed only by Tom Mix again, whose new arrangement with Fox paid $17,500.[60] Thomson's were among those few FBO films budgeted at or above $75,000, but they could be relied on to gross in the quarter-million-dollar range.[61] And Kennedy found an angle to make himself even more money. Under the new contract, Kennedy struck a deal in early 1927 with Paramount for the major studio to produce and distribute a series of four Thomson "super westerns". Kennedy participated in the films' financing, recouping his stake plus $100,000 in profits each; Paramount covered Thomson's weekly salary; and the actor's production unit stayed on the FBO lot.[62] Given the lag time between production and exhibition, of the four Thomson features that reached theaters in 1927, three were FBO releases.[63] The studio put out fifty-one features in total that year; for the twelve-month period ending November 15, theater owners judged FBO's top three films to all be Gene Stratton-Porter adaptations, with two Thomson oaters following.[64]

Sound enters the picture

The advent of

FBO's

On October 23, 1928, RCA announced it was merging Film Booking Offices and Keith-Albee-Orpheum to form the new motion picture business

Cinematic legacy

A large majority of FBO/Robertson-Cole pictures, produced during the silent era and the transitional period of the conversion to sound cinema, are considered to be lost films, with no copies known to exist. Much of FBO's cinematic legacy thus endures only in still images, other publicity materials, and written accounts. All told, just 30 percent of American silent feature films have been preserved (25 percent more or less complete, plus another 5 percent in incomplete versions). The overall survival rate of features produced by R-C/FBO is similar: of 449 movies identified by the National Film Preservation Board as R-C/FBO productions, 125 are known to survive in some form—28 percent, though with only two (0.4 percent) in a legacy studio archive.[82] The losses, moreover, were not equally distributed, and one of FBO's most successful franchises has disappeared entirely: not even a fragmentary print of any of the six Gene Stratton-Porter films put out by the studio has been found. Due to its zeal for cost cutting, FBO was reputed to be especially meticulous in the execution of a practice then common among distributors: rounding up its release prints at the end of a picture's run and melting them down to recover the silver in the film emulsion.[83]

As for FBO's biggest star, among America's biggest at the time, of the twenty films Fred Thomson made for the studio, for years just a single one was known to remain intact in a US archive: Thundering Hoofs. About three reels' worth of the five-reel

Headliners and celebrity casting

Sessue Hayakawa, the first star of any magnitude associated with the Robertson-Cole brand, made a total of twenty films released by the studio, from A Heart in Pawn in March 1919 to The Vermilion Pencil in March 1922.[89] Hayakawa was regarded as one of the finest screen performers of his time, but as anti-Japanese sentiment grew on the West Coast, R-C terminated its relationship with the Chiba-born actor. Two months after The Vermilion Pencil opened, he sued the studio for breach of contract.[90] Pauline Frederick, celebrated for her performance in the September 1920 Goldwyn Pictures tear-jerker Madame X, immediately cashed in with a top-tier contract from Robertson-Cole, for whom she starred in more than half a dozen melodramas, beginning with A Slave of Vanity just two months later.[91] She was said to have been paid an extravagant $7,000 or $7,500 a week under her R-C deal.[92] Early in her career, ZaSu Pitts acted in six R-C releases—Better Times (1919) gave Pitts her first ever top billing—from the Brentwood Film Corporation, founded by a group of doctors.[93]

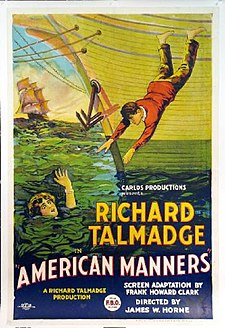

In the years after the studio's rebranding, Evelyn Brent and Richard Talmadge were FBO's most prominent non-Western headliners.[94] Brent made a specialty of melodramatic pictures with a crime angle, often billed as "crook melodramas"—in Midnight Molly (1925), she played an ambitious politician's faithless wife and her look-alike, a high-end cat burglar.[95] Talmadge, a stunt designer and double for major stars including Douglas Fairbanks and Harold Lloyd, took the lead in action pictures for FBO—"stunt dramas" such as Stepping Lively (1924) and Tearing Through (1925).[96] He appeared in eighteen FBO releases, more than half of them produced by his own company.[97] Talmadge's last film for the studio was released in June 1926.[98] By August, Brent was on her way to starring roles at Paramount.[99] In October, Talmadge was judged to have been FBO's biggest non-Western draw of the year; in the first annual Exhibitors Herald theater owners' poll of top box office names, he placed thirtieth out of sixty.[100]

Beginning in late 1924,

In its pre-Kennedy years, the studio did not hesitate to take advantage of scandal sheet–worthy events. After the death of celebrated actor Wallace Reid, brought on by morphine addiction, his widow, Dorothy Davenport, signed on as producer and star of a cinematic examination of the sins of substance abuse: Human Wreckage, released by FBO in June 1923, five months after Reid's death, in which Davenport (billed as Mrs. Wallace Reid) plays the wife of a noble attorney turned dope fiend.[111] A few months later, the studio featured a celebrity of a very different sort: magician Harry Houdini, directing and starring in his last feature film, Haldane of the Secret Service.[112] In November 1924, FBO put out Davenport's next "social problem" picture, Broken Laws. Here Davenport (again billed as Mrs. Wallace Reid) plays the overindulgent mother of an unruly boy destined, as a reckless teen, to commit a terrible misdeed. According to a trade journal—perhaps echoing publicity copy—the tale was "a reminder that the foundation of all law and order lies in that greatest of American institutions—the home."[113]

When the biggest movie star in the world, Rudolph Valentino, split from his wife, Natacha Rambova, she was swiftly enlisted by the studio to costar with Clive Brook in the sensitively titled When Love Grows Cold (1926).[114] Under Kennedy's control, the studio focused on marketing its roster of films as suitable for the "average American" and the entire family: "We can't make pictures and label them 'For Children,' or 'For Women' or 'For Stout People' or 'For Thin Ones.' We must make pictures that have appeal to all."[115] Though Kennedy ended the scandal-sheet specials, FBO still found occasion for celebrity casting: One Minute to Play (1926), directed by Sam Wood, marked the film debut of football great "Red" Grange.[116] Tennis stars Suzanne Lenglen and Mary Browne were signed for a series of "Racquet Girls" pictures that never made it to screen.[117]

Western and canine stars

Central to the FBO identity were Westerns and the studio's major cowboy star,

Among Western stars under long-term contract, FBO's next most important—though by a distance—was Tom Tyler, who finished twenty-third among men in the 1927 exhibitors' poll.[123] Born Vincent Markowski, he had been a weightlifter and bit actor before his transformation into a cowboy headliner.[124] According to a hyperbolic June 1927 report in Moving Picture World: "With Tom Tyler rapidly taking the place recently vacated by Fred Thomson [for the Paramount sojourn from which he would never return], F.B.O.'s program of western pictures is taking a place second to none in the industry. Tyler has made rapid strides during his two years with F.B.O. and with his horse 'Flash' and dog, 'Beans,' has become one of the leading favorites on the screen."[125] Tyler's appeal was also enhanced by his human costars—Frankie Darro (tied for fifty-fourth in the poll) as his young sidekick on over two dozen occasions and starlets such as Doris Hill, Nora Lane, Sharon Lynn, and in Born to Battle (1926), a twenty-five-year-old Jean Arthur.[126][127]

As 1928 began, Tyler was the most popular actor actually working at FBO, but Kennedy wanted the big gun. He bided his time as Tom Mix toured the Orpheum vaudeville theaters with a live show—boosting Kennedy's new exhibition interests—and legal machinations ensured Thomson's exile.[129] Finally, Mix was signed to a six-film deal and began shooting in July.[130] He ultimately made five pictures for the studio (two released after it had ceased to exist), and stayed near the top of the exhibitors' poll, his 112 votes good enough for second among the men, if well behind the 171 of MGM's Lon Chaney (no other FBO regular made it into even double digits).[131] But the spread of the talkies was swiftly making the silent sagebrush superstar less of a sure thing.[132] Variety derided Mix's last FBO film, The Big Diamond Robbery, released in May 1929, as "cowboy burlesque".[133] His brief tenure at the studio was marked by salary grievances—he was now making only $10,000 a week—and dismay at FBO's inferior production values, from its worndown sets to the cut-rate film stock it used.[134] Subsequently asked about his experience working with Kennedy, Mix described him as a "tight-assed, money-crazy son-of-a-bitch."[135]

In addition to these major draws, there was also

Notable films and filmmakers

Kennedy had no illusions about his studio's place in the realm of cinematic art. A journalist once complimented him on FBO's recent output: "You have had some good pictures this year." Kennedy jocularly inquired, "What the hell were they?"

Two of the studio's most impressive releases were foreign productions. In 1927, FBO picked up for U.S. distribution an acclaimed Austrian biblical spectacular made three years earlier:

At the age of twenty-five,

Author and naturalist

Short subjects and animation

Both George O'Hara's and Alberta Vaughn's initial short series for FBO—each directed by Malcolm St. Clair—were hits, so in the second half of 1924 the studio made a bid at teaming them in the twelve-part The Go-Getters, spoofing popular films and classic stories with chapters such A Kick for Cinderella. It was so successful that they were reunited the next year for a similar twelve-parter, The Pacemakers, with episodes such as Merton of the Goofies (Merton of the Movies) and Madam Sans Gin (Madame Sans-Gêne).[164] Vaughn had solo top billing in the comedic series The Adventures of Mazie (1925–26) and the baseball-themed serial Fighting Hearts (1926).[165] In May 1928, with the Keith-Albee-Orpheum theater chain under his control, Joseph Kennedy announced a forthcoming slate with not only more than the usual number of (relatively) high-budget films but a "Mammoth Program of Short Features". No less than four different series came from independent producer Larry Darmour, including the second twelve chapters of Mickey McGuire, starring seven-year-old Mickey Rooney. Amedee Van Beuren provided Walter Futter's Curiosities, a Ripley's-inspired "Movie Side Show" of "freaks and queer odds and ends from all corners of the world".[166]

Of particular historical interest are two independently produced series of slapstick comedies released by the studio: Between 1924 and 1927, Joe Rock provided FBO with a substantial annual slate of two-reelers (twenty-six per year as of their last contract); twelve of those from 1924–25 starred Stan Laurel, before his famous partnership with Oliver Hardy.[167] West of Hot Dog (1924), according to historian Simon Louvish, contains "one of [Laurel]'s finest gags," involving a level of cinematic technique that bears comparison to Buster Keaton's classic Sherlock Jr.[168] In 1926–27, the company released more than a dozen shorts by innovative comedian/animator Charles Bowers, whose work imaginatively mixed live action and three-dimensional model animation.[169]

FBO also distributed the output of significant creators of purely animated films. Between 1924 and 1926, FBO released the work of

Notes

- ^ Sherwood (1923), p. 150; Ellis and Thornborough (1923), p. 262.

- ^ Beauchamp (2010), p. 70.

- ^ Codori (2020), pp. 113–17; Nasaw (2012), pp. 68–69; Miyao (2007), p. 169. Beauchamp (2009, p. 35), among others, misidentifies Cole as British.

- ^ Codori (2020), p. 113–14; Nasaw (2012), p. 69.

- ^ Slide (2013), p. 3; Miyao (2007), p. 169; Codori (2020), p. 114–15. "The Girl of My Dreams (1918)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 27, 2022. "And a Still Small Voice (1918)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ a b "Robertson-Cole Buys" (PDF). Variety. January 1920. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- doi:10.4000/map.2385. In May 1916, five after months the release of his breakout film, The Cheat, a similar poll had ranked him number one. Miyao (2007), p. 3.

- ^ Codori (2020), p. 114; Slide (2013), p. 175.

- ^ "Short Robertson-Cole Offerings: Supreme Comedies, Martin Johnson's Cannibal Films and Adventure Scenics Offer Variety". Motion Picture News. November 15, 1919. p. 3597. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ Codori (2020), p. 115; Jewell (1982), p. 8.

- ^ "Branch Officials of Robertson-Cole Will Confer in New York". Exhibitors Herald. March 20, 1920. p. 44. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ "Guide to Current Pictures: Robertson-Cole Pictures". Exhibitors Herald. March 20, 1920. p. 98; see also pp. 78–79. Retrieved October 27, 2022. See also Codori (2020), p. 116.

- ^ "Reviews: The Third Woman". Exhibitors Herald. March 20, 1920. p. 55; see also p. 98. Retrieved October 27, 2022. "The Third Woman (1920)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 27, 2022. "The Wonder Man (1920)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 27, 2022. "Carpentier Film Shown; French Champion Appears Under the Auspices of the Legion Here". New York Times. May 30, 1920. Retrieved October 26, 2022. While the AFI catalog describes The Wonder Man as "the first picture produced by Robertson-Cole" (Jewell [1982], p. 8, uses almost identical language), The Third Woman was clearly released first. Indeed, though AFI lists The Third Woman as an April release, it was both reviewed and listed as a "current picture" in the Exhibitors Herald cover dated March 20—and actually published ten days earlier. "Announcement: Change of Practice of Cover Line Dating". Exhibitors Herald. December 25, 1925. p. 43. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

The production history of the March 1920 R-C release A Woman Who Understood is unclear. A film from star Bessie Barriscale's own production company had come out as recently as February (The Luck of Geraldine Laird); as AFI notes, Variety referred to A Woman Who Understood as a "'B.B.' feature," and at least one print ad identified it as a "B.B. Picture". Stating that "no other information has been located connecting this to Bessie Barriscale's own company", AFI lists it as an R-C production. "A Woman Who Understood (1920)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 27, 2022. A detailed survey of her career from the Women Film Pioneers Project lists it under B.B. Features/B. B. Productions. Lund, Maria Fosheim (2013). "Bessie Barriscale". Women Film Pioneers Project. Columbia University Libraries. Retrieved October 28, 2022. - —the old FBO facility occupies the western quarter of the Paramount Studios area. For images of the studio's administration building during its FBO days, see Crafton (1997), p. 136; Beauchamp (2009), p. 77.

- ^ "Robertson-Cole Buys a Ranch". Motion Picture News. June 26, 1920. p. 83. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ Shiel (2012), p. 149.

- ^ Jewell (1982), p. 8. "Kismet (1920)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ Miyao (2007), p. 169.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), pp. 33–37; Goodwin (1987), pp. 340–41; Nasaw (2012), pp. 68–71, 73.

- ^ Jewell (1982), p. 8. "The Mistress of Shenstone (1921)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 27, 2022. "The Mistress of Shenstone [review]". Moving Picture World. March 5, 1921. p. 45; see also p. 80. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), pp. 38–44; Goodwin (1987), pp. 340, 342; Nasaw (2012), pp. 69–70, 73–74; Beauchamp (1998), p. 157.

- ^ Goodwin (1987), p. 341; Beauchamp (1998), p. 157; Jewell (1982), p. 8.

- ^ Lasky (1989) p. 13; Jewell (1982), p. 8. In February 1922, while plans for the reorganization were underway, the business was structured thus: R-C Pictures Corporation as parent company, Robertson-Cole Studios Inc. as production subsidiary, and Robertson-Cole Distributing Corporation as distribution subsidiary. Graham's owned all the capital stock in the companies. H.C.S. Thomson (of Graham's) was chairman of the board of R-C Pictures Corp. and Pat Powers was its managing director. The board of directors of Robertson-Cole Studios Inc. comprised Rufus Cole, Joseph Kennedy, Erskine Crum (of Graham's), W. W. Lancaster (of Lloyd's of London), and R. J. Tobin. In May, founder Rufus Cole resigned as both director and president of Robertson-Cole Studios, and Powers became its managing director. "Offeman v. Robertson-Cole Studios, Inc". Casetext. November 26, 1926. Retrieved October 29, 2022. See also Beauchamp (2009), p. 74.

Many sources give FBO's full name incorrectly as "Film Booking Office of America"; the proper name is Film Booking Offices of America, as per the company's official logo. For the correct spelling, see Sherwood (1923), pp. 150, 156, 158, 159, etc.; Ellis and Thornborough (1923), p. 262. - ^ Trade paper reports on production plans in 1925 contain no mention of Robertson-Cole as business or brand. "Thomson in New Series; Flynn Signs to Make Eight Pictures for F.B.O." Moving Picture World. May 23, 1925. p. 104. Retrieved November 1, 2022. Smith, Sumner (August 1, 1925). "Thomson of F.B.O. Discusses 'Bread and Butter' Pictures". Moving Picture World. p. 506. Retrieved October 29, 2022. "F.B.O. Sets Releases on Program for September". Moving Picture World. August 1, 1925. p. 559. Retrieved October 29, 2022. "F.B.O. Launches Western Drive". Exhibitors Trade Review. November 7, 1925. p. 27. Retrieved October 29, 2022. The reference in Beauchamp (1998) to Kennedy's February 1926 takeover of "R-C Pictures Corporation and Film Booking Office [sic] of America" (p. 180) suggests that the parent company retained its Robertson-Cole identity at that point. The 1927 logo reproduced at the top of this article, reading "FBO Pictures Corp.", and a brief trade report from June of that year indicate that the corporate name of the parent company was changed after the Kennedy purchase. "F.B.O. Is Now FBO". Moving Picture World. June 11, 1927. p. 403. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Lasky (1989), p. 13. See, e.g., "Vintage Railroad Melodramas to Be Accompanied by Live Music Sunday". Concord Monitor. October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Jewell (2012), p. 10.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), pp. 50–53, 79–80; Beauchamp (1998), pp. 157–58.

- ^ Foote (2014), p. 100; Wing (1924), p. 193; Carr, Harry (September 1923). "Art...and Right Hooks: The Story of George O'Hara". Motion Picture. pp. 21–22, 88. Retrieved November 3, 2022. "Fighting Blood [ad]". Exhibitors Herald. September 29, 1923. p. 75. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Ankerich (2010), chap. Alberta Vaughn.

- ^ Solomon (2011), p. 71.

- ^ Rainey (1999), p. 234.

- ^ "Offeman v. Robertson-Cole Studios, Inc". Casetext. November 26, 1926. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ Jewell (1982), p. 8.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. 80. Beauchamp directly cites the contract for the details here (note, p. 423), silently correcting her earlier claim (Beauchamp [1998], p. 168) that Thomson's new deal paid him $10,000 a week, implausibly exceeding Mix.

- ^ "The Biggest Money-Makers of 1925". Exhibitors Herald. December 25, 1925. pp. 54–57. Retrieved November 1, 2022. Lussier (2018), p. 95.

- ^ Beauchamp (1998), p. 157; Lasky (1989), pp. 14–15.

- ^ Jewell (2012), pp. 9–10; Lasky (1989), pp. 14–17.

- ^ Pierce, David (September 2013). "The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929" (PDF). Library of Congress. p. 41. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ "Thomson of F.B.O. Discusses 'Bread and Butter' Pictures". Moving Picture World. August 1, 1925. p. 506. Retrieved October 29, 2022. "F.B.O. Sets Releases on Program for September". Moving Picture World. August 1, 1925. p. 559. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ Kear (2009), pp. 30, 142–44, 146–48. "Search Results: 'Gothic Pictures'". American Silent Feature Film Database. Library of Congress. Retrieved November 4, 2022. "Search Results: 'Gothic Productions'". American Silent Feature Film Database. Library of Congress. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Lasky (1989), pp. 12–13, 14–15; Beauchamp (1998), p. 180.

- ^ Quoted in Lasky (1989), p. 12.

- ^ Goodwin (1987), pp. 342–43; Beauchamp (1998), p. 180; Lasky (1989), p. 13; Beauchamp (2009), pp. 66–68.

- ^ Nasaw (2012), pp. 94–95; Lasky (1989), pp. 14–15; Goodwin (1987), p. 344; Beauchamp (2009), pp. 73–74. Lasky misspells Kennedy's new firm as the Cinema "Credit" Corporation.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), pp. 74–75, 82–83; Goodwin (1987), pp. 345, 346.

- ^ Nasaw (2012), pp. 100–2; Beauchamp (1998), pp. 180, 197. For Hays and Kennedy's earlier association, see Goodwin (1987), p. 341; Nasaw (2012), pp. 75–76; Beauchamp (2009), pp. 48–49.

- ^ Ramsaye, Terry (September 1927). "Intimate Visits to the Homes of Famous Film Magnates". Photoplay. pp. 50–51, 122–25 (quote at 125). Retrieved December 26, 2022. Beauchamp (1998), p. 180; Nasaw (2012), p. 103. Beauchamp misleadingly suggests that Ramsaye's words were Hays's (which she does again in Beauchamp [2009], p. 68.)

- ^ Kear (2009), p. 38.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. 83; Lasky (1989), p. 15; Jewell (1982), p. 9.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. xvi.

- ^ Goodwin (1987), p. 347–48; Lasky (1989), p. 14.

- ^ Goodwin (1987), p. 347.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. 84. See also Kear (2009), p. 38.

- ^ Goodwin (1987), p. 348.

- ^ "The Biggest Money Makers of 1926". Exhibitors Herald. December 25, 1926. pp. 54–57. Retrieved November 1, 2022. "The Keeper of the Bees (1925)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 29, 2022. Murray, Ray (June 27, 1925). "Hollywood: Millions of Dollars Are Going into Pictures for New Season". Exhibitors Herald. p. 58. Retrieved November 1, 2022. Stratton-Porter, Gene (February 1925). "The Keeper of the Bees [part 1]". McCall's. pp. 5–7, 27–28, 47, 49. Retrieved November 1, 2022. Stratton-Porter, Gene (September 1925). "The Keeper of the Bees [part 8]". McCall's. p. 24, 26, 56, 62, 70. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ Goodwin (1987), p. 348; Jewell (1982), p. 9.

- ^ Finler (1988), p. 36.

- ^ "Staff Writers Are Banned at F.B.O. Studios". Moving Picture World. June 11, 1927. p. 405. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), pp. 89–90; Beauchamp (1998), pp. 210, 211; Jensen (2005), pp. 97, 116–17, 122, 128; Koszarski (1990), p. 116.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. 80.

- ^ Beauchamp (1998), pp. 211, 217, 227; Beauchamp (2009), p. 164.

- ^ McCaffrey and Jacobs (1999), p. 266.

- ^ Nasaw (2012), pp. 106–7; "The Biggest Money Makers of 1927". Exhibitors Herald. December 24, 1927. pp. 145–46. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ Jewell (2012), p. 12; Lasky (1989), pp. 24–25; Nasaw (2012), pp. 111–12; Beauchamp (2009), p. 141.

- ^ Lasky (1989), pp. 25–26; Jewell (2012), pp. 13–15; Nasaw (2012), pp. 115–17, 119–20; Beauchamp (2009), pp. 141–45, 147–52; "Cinemerger". Time. May 2, 1927. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ "The Man...the Product and the Master Showmen of the World [ad]". Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World. May 19, 1928. pp. 4–5. Retrieved July 8, 2023. For Kennedy's self-promotion while at FBO, see Beauchamp (2009), pp. 158–59, 194–97.

- ^ Crafton (1997), p. 140. According to Crafton, The Perfect Crime was first released on June 17. At a time when few theaters in the country were wired for sound, many of those with only the incompatible Vitaphone sound-on-disc system—see Block and Wilson (2010), p. 56; Crafton (1997), pp. 148–49—the film's limited run before its Rivoli debut was in the silent version in which it was shot. In the fifty-two pages of color ads Kennedy bought at the front of the May 19 Exhibitors Herald to promote FBO's upcoming slate of pictures, the two-page spread for The Perfect Crime has pride of place behind only Kennedy himself. There is no mention of sound. "The Perfect Crime [ad]". Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World. May 19, 1928. pp. 6–7. Retrieved October 28, 2022. Another two-page ad, in the July 7 issue, claiming the film has "Amazed...and Astounded the Critics" and is the "First Real Hit of 28-29", again makes no mention of sound. "The Perfect Crime [ad]". Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World. July 7, 1928. pp. 20–21. Retrieved October 28, 2022. Finally, a spread in the August 11 issue blares, "FBO Sound Sensation Scores Solid Broadway Smash", asserts that the film has been "A Hit in Silent Form" in Los Angeles and Detroit, and reassures that "FBO has not forgotten the thousands of showmen who have not yet obtained sound installations". "The Perfect Crime [ad]". Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World. August 11, 1928. pp. 26–27. Retrieved October 28, 2022. For the Rivoli, see "Rivoli Theatre". NYC AGO. New York City Chapter of the American Guild of Organists. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ Crafton (1997), pp. 140, 304; Koszarski (1990), p. 169; "FBO Completes First 'Talkie'; Now Synchronizing Five Others". Exhibitors Herald. August 11, 1928. p. 31. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ "The Screen: That Old Devil Crime". New York Times. August 6, 1928. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- JSTOR 3051829.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. 203; Lasky (1989), pp. 29, 33; Crafton (1997), p. 141. Lasky's claim that Kennedy at that point also tendered RCA an option to acquire control of FBO appears to be erroneous (the claim is echoed by Crafton, citing only Lasky); neither Kennnedy biographers Goodwin, Beauchamp, or Nasaw nor preeminent RKO historian Jewell offer any support for it. Lasky and thus Crafton also mistakenly state that Kennedy left on vacation after the August 22 announcement; in fact, his ship sailed on Friday, August 17. Nasaw (2012), p. 126; Beauchamp (2009), pp. 206–7.

- ^ Nasaw (2012), pp. 129–31.

- ^ Jewell (2012), p. 16.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), pp. 218–20, 230–31; Jewell (2012), p. 18; Nasaw (2012), pp. 130–31.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. 224; Jewell (2012), p. 18.

- ^ Lasky (1989), p. 43. For LeBaron's hiring the previous year, see Beauchamp (2009), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Staff of Exhibitors Herald-World (1929). "Money Making Stars and Pictures of 1928". Motion Picture Almanac. pp. 145–46. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ Jewell (1988), p. 20.

- ^ "Pals of the Prairie (1929)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ In 1924, for example, 586 American features (five reels or longer) were released. Solomon (2011), p. 71. "The Biggest Money-Makers of 1925". Exhibitors Herald. December 25, 1925. pp. 54–57. Retrieved November 1, 2022. "The Biggest Money Makers of 1926". Exhibitors Herald. December 25, 1926. pp. 38–39. Retrieved November 1, 2022. "The Biggest Money Makers of 1927". Exhibitors Herald. December 24, 1927. pp. 36–37. Retrieved October 29, 2022. Staff of Exhibitors Herald-World (1929). "Money Making Stars and Pictures of 1928". Motion Picture Almanac. pp. 145–46. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ Pierce, David (September 2013). "The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929" (PDF). Library of Congress. pp. 1, 41, and passim. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ Grayson, Eric (Winter 2007). "Limberlost Found: Indiana's Literary Legacy in Hollywood". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. pp. 42–47. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ Boggs (2011), p. 44; Katchmer (2002), p. 371; Pierce, David. "Silent Movie Cowboy Star Fred Thomson: Cowboy Films". Readers of the Purple Sage Western Bookstore. Nordell Online Bookstores Group. Retrieved November 2, 2022. "Galloping Gallagher (1924)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ Firestone (2010), pp. 73, 77.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), pp. 235–36.

- ^ According to the ASFFD, versions of the following are held outside the United States: The Mask of Lopez (1924), North of Nevada (1924), Ridin' the Wind (1925), The Tough Guy (1926), The Two-Gun Man (1926), Lone Hand Saunders (1926), and Arizona Nights (1927). Abridged prints of The Bandit's Baby and That Devil Quemado (both 1925) exist somewhere in private hands. "Search Results: 'Fred Thomson' [+] FBO". American Silent Feature Film Database. Library of Congress. Retrieved November 2, 2022. Galloping Gallagher is not in the database at all, for reasons unknown. All four of Thomson's Paramount "super westerns" are considered lost. Beaumont (2009), p. 443.

- ^ Kear (2009), pp. 142–48.

- ^ Miyao (2007), p. 334; "A Heart in Pawn (1919)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 28, 2022. "The Vermilion Pencil (1922)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- doi:10.4000/map.2385.

- ^ Davies (1971), p. 666. Frederick made seven known films for the company between 1920 and 1922 and one more in 1926. There is a question about the status of a ninth project: The Woman Breed (supposedly 1922). There is no doubt a screenplay was written and shooting was planned. But the last AFI print catalog states, in its terse entry for The Woman Breed, "Because it is unusual to find no information on an FBO or Pauline Frederick film (all facts here are from the Film Year Book, 1923), it can be concluded that this film was also known by another title." The current online AFI catalog has no entry for it at all. Beeman, Renee (February 18, 1922). "Live News of the West Coast". Exhibitors Trade Review. p. 823. "New Story by Louis Stevens, to Pauline Frederick". Canadian Moving Picture Digest. March 18, 1922. p. 17. Munden (1997), p. 917. For a helpful Frederick filmography, which does not include The Woman Breed, see "The Films of Pauline Frederick". The Pauline Frederick Website. Stanford University. December 18, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ Liebman (2017), p. 102; Davies (1971), p. 666.

- ^ Stumpf (2010), pp. 13–14, 116–17; Slide (2013), p. 27.

- ^ Jewell (1982), p. 8; Kear (2009), pp. 31–38, 142, 144–45, 147; Lasky (1989), p. 16.

- ^ Kear (2009), pp. 31, 35, 144–45; "Midnight Molly [ad]". Moving Picture World. January 31, 1925. p. 414. Retrieved November 1, 2022. Sewell, C. S. (February 7, 1925). "Midnight Molly [review]". Moving Picture World. pp. 558, 586. Retrieved November 2, 2022. Reid, Laurence (July 4, 1925). "Smooth as Satin [review]". Moving Picture World. p. 101. Retrieved November 1, 2022. "F.B.O. Sets Releases on Program for September". Moving Picture World. August 1, 1925. p. 559. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ Freese (2014), pp. 3, 93, 171, 278; Smith, Sumner (August 1, 1925). "Thomson of F.B.O. Discusses 'Bread and Butter' Pictures". Moving Picture World. p. 506. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ Laughing at Danger (1924) through The Better Man (1926). "Richard Talmadge". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ "The Better Man (1926)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ Kear (2009), pp. 38–40, 148–50.

- ^ "60 Best Box Office Names". Exhibitors Herald. October 30, 1926. pp. 54–57. Retrieved October 28, 2022. Though Talmadge made few actual Westerns, in categorizing male stars as "drama and comedy drama", "Western", or "comedian", the trade journal placed him with the cowboys. Brent's first Paramount feature, Love 'Em and Leave 'Em, had not reached most theaters when the poll was conducted, and she made it only onto the unranked long list of "240 Box Office Names".

- ^ The AFI Flynn filmography, which is organized by year of release but not month, shows thirteen such films: The No-Gun Man and The Millionaire Cowboy (both 1924), then Smilin' at Trouble (1925) through The College Boob (1926). "Lefty Flynn". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 1, 2022. Smith, Sumner (August 1, 1925). "Thomson of F.B.O. Discusses 'Bread and Butter' Pictures". Moving Picture World. p. 506. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ "Thomson in New Series; Flynn Signs to Make Eight Pictures for F.B.O." Moving Picture World. May 23, 1925. p. 104. Retrieved November 1, 2022. Christgau (1999), pp. 55–59. "New Pictures: Speed Wild". Moving Picture World. June 6, 1925. p. 63. Retrieved November 1, 2022. "New Pictures: High and Handsome". Exhibitors Herald. September 19, 1925. p. 58. Retrieved November 1, 2022. Connelly (1998), p. 105.

- ^ Long (2012), pp. 16–20; Jewell (1982), p. 8. "In the Name of the Law (1922)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022. "The Third Alarm (1923)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022. "The Westbound Limited (1923)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022. "The Mailman (1923)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022. "Untamed Youth (1924)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022. "The Last Edition (1925)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022. "Bigger than Barnum's (1926)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022. "Crooks Can't Win (1928)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Rainey (1999), p. 177.

- ^ Jewell (1982), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Jewell (1982), pp. 8–9. Nilsson: "Vanity's Price (1924)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022. "Blockade (1928)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022. Fairbanks: "Dead Man's Curve (1928)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022. "The Jazz Age (1929)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Nollen (1991), pp. 34, 356.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. 84; "Search Results: 'Viola Dana' [+] FBO". American Silent Feature Film Database. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ Vogel (2010), pp. 5, 94, 105–6.

- ^ Nollen (1991), pp. 31–32, 354–58; Kear (2009), pp. 144–46.

- ^ Schaefer (1999), p. 224; Slide (2022), pp. 85–88; Taves (2012), chap. Initial Distribution beyond First National, 1923.

- ^ Jewell (2012) p. 10; "Haldane of the Secret Service [ad]". Exhibitors Herald. October 27, 1923. p. 75. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Lussier (2018), p. 95; Slide (2022), p. 88; "F.B.O. Has Excellent Material Lined Up for Fall and Winter". Moving Picture World. July 12, 1924. p. 123. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ Goodwin (1987), p. 341; "Rambova F.B.O. Picture Titled 'When Love Grows Cold'". Exhibitors Herald. December 25, 1925. p. 40. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ^ Quoted in Goodwin (1987), p. 347.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), pp. 80–82, 87; Hall, Mordaunt (September 6, 1926). "The Screen: 'Red' Grange's First Film". New York Times. Retrieved October 29, 2022. See also Heritage Vintage (2004b), p. 121.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. 82.

- ^ Mayer (2017), p. 280. Cf. Katchmer (2002), p. 380. Katchmer misdates Let's Go, Gallagher as 1924 and omits The Cowboy Cop (1926), Tom and His Pals (1926), and Terror Mountain (1928) from his Tyler filmography. "Let's Go, Gallagher (1925)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 28, 2022. "The Cowboy Cop (1926)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 28, 2022. "Tom and His Pals (1926)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 28, 2022. "Terror Mountain (1928)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 28, 2022. "The Pride of Pawnee (1929)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Beauchamp (1998), p. 224; "The Big Names of 1927". Exhibitors Herald. December 31, 1927. pp. 22–23. Retrieved October 27, 2022. "60 Best Box Office Names". Exhibitors Herald. October 30, 1926. p. 54. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Lasky (1989), p. 16.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), pp. 165–67, 208. Nasaw (2012)—incredibly citing Beauchamp—writes, "Kennedy did everything he could to keep Thomson's career alive" (p. 107), a gross falsehood.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), pp. 233–36. Kennedy even profited from Thomson's death, as Fred Thomson Productions had taken out a $150,000 life insurance policy on the performer. Beauchamp (2009), pp. 234–35.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. 82; "The Big Names of 1927". Exhibitors Herald. December 31, 1927. pp. 22–23. Retrieved October 27, 2022. He placed thirty-fourth in the previous year's poll, which was not divided by sex. "60 Best Box Office Names". Exhibitors Herald. October 30, 1926. p. 54. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. 82. Beauchamp misleadingly implies that Kennedy oversaw the transformation, but Let's Go, Gallagher, the first film with Tyler as lead, opened in August 1925, half a year before Kennedy took over FBO.

- ^ "F.B.O. Has Ambitious Program of 20 Westerns for 1927-28". Moving Picture World. June 11, 1927. p. 422. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Katchmer (2002), p. 380; Rainey (1987), p. 139.

- ^ a b c "The Big Names of 1927". Exhibitors Herald. December 31, 1927. pp. 22–23. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ "Preparing for Mix". Variety. April 4, 1928. p. 14. Retrieved July 7, 2023. "Inside Stuff—Pictures". Variety. April 11, 1928. p. 45. Retrieved July 7, 2023. Beauchamp (2009), pp. 165–66.

- ^ Jensen (2005), pp. 119; Beauchamp (2009), pp. 165–67. For Mix's vaudeville circuit tour, see also "Tom & Tony 'Stand 'Em Up'". Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World. April 28, 1928. p. 18. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ Jensen (2005), pp. 120; Brichard (1993), p. 216; "Tom Mix and Tony Are FBO Stars". Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World. May 19, 1928. p. 89. Retrieved July 7, 2023..

- ^ Staff of Exhibitors Herald-World (1929). "Money Making Stars and Pictures of 1928". Motion Picture Almanac. pp. 144–45. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ Jensen (2005), pp. 116–18, 120–23.

- ^ Jensen (2005), p. 123.

- ^ Brichard (1993), pp. 216–18; Jensen (2005), pp. 121–24; Lasky (1989), p. 17.

- ^ Quirk (1996), p. 303.

- ^ Mayer (2017), p. 69; Katchmer (1991), pp. 122–24, 133.

- ^ Lasky (1989), pp. 16–17; Katchmer (2002), pp. 17, 83.

- ^ Beauchamp (2009), p. 82. The suggestion by Goodwin (1987) that, during Kennedy's tenure, FBO made "a dozen dog pictures...each year" (p. 348) is exaggerated. Ranger, the studio's only canine headliner of the Kennedy era, starred in sixteen pictures over the course of three years.

- ^ For examples of how such films were marketed, see Heritage Vintage (2004a), p. 79, and Heritage Vintage (2005), p. 35. In the latter, the text accompanying the poster of Tom and His Pals (1926) incorrectly identifies it as a Paramount picture and suggests it was the first film teaming Tyler and Darro (it was the ninth).

- ^ Sandburg (1925), pp. 270–71.

- ^ Valderrama (2020), p. 21.

- ^ Fenton (2002), pp. 106–7; Armstrong and Armstrong (2001), pp. 196–97; Mayer (2017), p. 37.

- ^ Quoted in Lasky (1989), p. 14.

- ^ Lasky (1989), p. 14.

- ^ Slide (2022), pp. 88–89; Lussier (2018), pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b Quoted in Fenton (2002), p. 107.

- ^ Kemp (1987), p. 173.

- ^ Finkielman (2004), p. 84.

- ^ Finler (1988), pp. 173, 184–85.

- ^ Armstrong (2007), p. 235; Sweeney (2007), p. 210.

- ^ Stumpf (2010), pp. 13, 116.

- ^ Koszarski (1990), p. 271. "Good Women (1921)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 26, 2022. "The Call of Home (1922)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 26, 2022. Gasnier also produced (but did not direct) the R-C releases The Beloved Cheater (1919) and The Butterfly Man (1920) with his own production companies. Codori (2020), p. 116.

- ^ Ince starred in the five movies atop the following list of his directorial efforts for FBO: "Search Results: 'Ralph Ince' [+] FBO". American Silent Feature Film Database. Library of Congress. Retrieved November 5, 2022. For the three films starring Evelyn Brent he directed, see Kear (2009), pp. 31–34, 144–46.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (March 6, 1928). "The Screen: An Irish Mother. Bootleggers and Night Clubs". New York Times. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ McCaffrey and Jacobs (1999), p. 166; "Salvage [review]". Variety. June 17, 1921. p. 34. Retrieved November 5, 2022. "Sting of the Lash [review]". Variety. October 21, 1921. p. 36. Retrieved November 5, 2022..

- ^ Kear (2009), pp. 30, 43, 142–44. For further description of the latter, see Langman (1998), p. 88.

- ^ Lupack (2020), pp. 248–50; Taves (2012), chap. Initial Distribution beyond First National, 1923; "Search Results: 'William Seiter' [+] FBO". American Silent Feature Film Database. Library of Congress. Retrieved November 5, 2022. "Search Results: 'William Seiter' [+] 'Palmer Photoplay'". American Silent Feature Film Database. Library of Congress. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Fleming (2007), p. 269; "Search Results: 'Emory Johnson' [+] FBO". American Silent Feature Film Database. Library of Congress. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Everson (1998), p. 142.

- ^ Grayson, Eric (Winter 2007). "Limberlost Found: Indiana's Literary Legacy in Hollywood". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. p. 44. Retrieved October 26, 2022. "The Harvester (1927)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 26, 2022. "Freckles (1928)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 26, 2022. Quoting raves from the New York Daily News and Motion Picture Journal, FBO promoted A Girl of the Limberlost as "the surprise picture of the year." "We've Quit Guessing [ad]". Exhibitors Herald. October 18, 1924. p. 115. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ Beauchamp (1998), pp. 168, 181, 211–12, 451–52.

- ^ Jackson, Markoe, and Markoe (1998), p. 28; Lasky (1989), pp. 105–18, 133–36, 152–57, 174–75.

- ^ Morton (2005), p. 43.

- ^ Foote (2014), pp. 100–1; Ankerich (2010), chap. Alberta Vaughn; Rainey (1999), p. 177.

- ^ Ankerich (2010), chap. Alberta Vaughn; Rainey (1999), pp. 12, 76; "F.B.O. Sets Releases on Program for September". Moving Picture World. August 1, 1925. p. 559. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ "World's Greatest Rodeo [ad]". Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World. May 19, 1928. pp. 45, 49–53. Retrieved October 30, 2022. Erickson (2020), pp. 74–76.

- ^ Erickson (2020), p. 74; Okuda and Neibaur (2012), pp. 129–65.

- ^ Louvish (2001), pp. 171–72.

- ^ Crafton (1993), p. 362 n. 39; Bourne, Mark (2004). "Charley Bowers: The Rediscovery of an American Comic Genius". DVD Journal. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ^ Crafton (1993), pp. 186–87; Langer (1995), pp. 105, 259 n. 40. For posters of two Bray/Lantz cartoons distributed by FBO, see Heritage Vintage (2004b), p. 51.

- ^ Barrier (2003), pp. 30, 48; Coar, Bob (March 7, 2022). "That Crazy Cat Bill Nolan". Cartoon Research. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Barrier (2008), pp. 51–53; Crafton (1993), p. 285; Langer (1995), p. 259 n. 39; Coar, Bob (March 7, 2022). "That Crazy Cat Bill Nolan". Cartoon Research. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

Sources

- Ankerich, Michael G. (2010). Dangerous Curves atop Hollywood Heels: The Lives, Careers, and Misfortunes of 14 Hard-Luck Girls of the Silent Screen. Duncan, OK: BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-59393-605-1

- Armstrong, Richard (2007). "James W. Horne," in The Rough Guide to Film, by Richard Armstrong, Tom Charity, Lloyd Hughes, and Jessica Winter. London: Rough Guides, p. 210. ISBN 978-1-84353-408-2

- Armstrong, Richard B., and Mary Williams Armstrong (2001). Encyclopedia of Film Themes, Settings and Series. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4572-1

- Barrier, Michael (2003). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516729-5

- Barrier, Michael (2008). The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25619-4

- Beauchamp, Cari (1998). Without Lying Down: Frances Marion and the Powerful Women of Early Hollywood. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21492-7

- Beauchamp, Cari (2009). Joseph P. Kennedy Presents: His Hollywood Years. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-1400040001

- Birchard, Robert S. (1993). King Cowboy: Tom Mix and the Movies. Burbank, CA: Riverwood Press. ISBN 978-1-880756-05-8

- Block, Alex Ben, and Lucy Autrey Wilson, eds. (2010). George Lucas's Blockbusting: A Decade-by-Decade Survey of Timeless Movies Including Untold Secrets of Their Financial and Cultural Success. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-177889-6

- Boggs, Johnny D. (2011). Jesse James and the Movies. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4788-6

- Buehrer, Beverley Bare (1993). Boris Karloff: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-27715-X

- Christgau, John (1999). The Origins of the Jump Shot: Eight Men Who Shook the World of Basketball. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6394-5

- Codori, Jeff (2020). Film History through Trade Journal Art, 1916–1920. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-7617-3

- Connelly, Robert B. (1998). The Silents: Silent Feature Films, 1910–36. Chicago: December Press. ISBN 978-0913204368

- Corneau, Ernest N. (1969). The Hall of Fame of Western Film Stars. Hanover, MA: Christopher Publishing House. ISBN 0-8158-0124-6

- Crafton, Donald (1993). Before Mickey: The Animated Film, 1898–1928. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-11667-0

- Crafton, Donald (1997). The Talkies: American Cinema's Transition to Sound, 1926–1931. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-19585-2

- Davies, Wallace Evan (1971). "Frederick, Pauline," in Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary, ed. Edward T. James. Cambridge, MA, and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-62734-2

- Ellis, Don Carlos, and Laura Thornborough (1923). Motion Pictures in Education: A Practical Handbook for Users of Visual Aids. New York: Thomas V. Crowell.

- Erickson, Hal (2020). A Van Beuren Production: A History of the 619 Cartoons, 875 Live Action Shorts, Four Feature Films, and One Serial of Amedee Van Beuren. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-8027-9

- Everson, William K. (1998). American Silent Film. New York: Da Capo. ISBN 0-306-80876-5

- Fenton, James W. (2002). Edgar Rice Burroughs and Tarzan: A Biography of the Author and His Creation. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1393-X

- Finkielman, Jorge (2004). The Film Industry in Argentina: An Illustrated Cultural History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1628-9

- Finler, Joel W. (1988). The Hollywood Story. New York: Crown. ISBN 0-517-56576-5

- Firestone, Bruce M. (2010 [1982]). "Fred Thomson," in American Classic Screen Profiles, ed. John C. Tibbetts and James M. Welsh. Lanham, MD: Firestone Press, p. 73–77. ISBN 978-0-8108-7677-4

- Fleming, E. J. (2007). Wallace Reid: The Life and Death of a Hollywood Idol. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7725-8

- Foote, Lisle (2014). Buster Keaton's Crew: The Team Behind His Silent Films. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9683-9

- Freese, Gene Scott (2014). Hollywood Stunt Performers, 1910s–1970s: A Biographical Dictionary, 2nd ed. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7643-5

- Gates, Philippa (2019). Criminalization/Assimilation: Chinese/Americans and Chinatowns in Classical Hollywood Film. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813589428

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns (1987). The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys: An American Saga. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-23108-1

- Heritage Vintage Movie Poster Signature Auction #603. Dallas: Heritage Vintage Movie Posters, 2004a. ISBN 1-932899-15-4

- Heritage Vintage Movie Poster Signature Auction #607. Dallas: Heritage Vintage Movie Posters, 2004b. ISBN 1-932899-35-9

- Heritage Vintage Movie Poster Signature Auction #624. Dallas: Heritage Vintage Movie Posters, 2005. ISBN 1-59967-004-6

- Jackson, Kenneth T., Karen Markoe, and Arnie Markoe (1998). The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, vol. 1: 1981–1985. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-68480-492-7

- Jensen, Richard D. (2005). The Amazing Tom Mix: The Most Famous Cowboy of the Movies. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-35949-3

- Jewell, Richard B. (2012). RKO Radio Pictures: A Titan Is Born. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27178-4

- Jewell, Richard B., with Vernon Harbin (1982). The RKO Story. New York: Arlington House/Crown. ISBN 0-517-54656-6

- Katchmer, George A. (1991). Eighty Silent Film Stars: Biographies and Filmographies of the Obscure to the Well Known. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0899504940

- Katchmer, George A. (2002). A Biographical Dictionary of Silent Film Western Actors and Actresses. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4693-3

- Kear, Lynn, with James King (2009). Evelyn Brent: The Life and Films of Hollywood's Lady Crook. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4363-5

- Kemp, Philip (1987). "Curtiz, Michael," in World Film Directors, Volume 1: 1890–1945, ed. John Wakeman. New York: H. W. Wilson, pp. 172–81. ISBN 0-8242-0757-2

- Koszarski, Richard (1990). An Evening's Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915–1928. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08535-3

- Langer, Mark (1995). "John Randolph Bray: Animation Pioneer," in American Silent Film: Discovering Marginalized Voices, ed. Gregg Bachman and Thomas J. Slater. Carbondale: Southern Illinois Univ. Press (2002), pp. 94–114. ISBN 0-8093-2402-4

- Langman, Larry (1998). American Film Cycles: The Silent Era. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30657-5

- Lasky, Betty (1989). RKO: The Biggest Little Major of Them All. Santa Monica, CA: Roundtable. ISBN 0-915677-41-5

- Liebman, Roy (2017). Broadway Actors in Films, 1894–2015. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7685-5

- Long, Harry H (2012). "Avenging Conscience," in American Silent Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy Feature Films, 1913–1929, vol. 1, by John T. Soister and Henry Nicolella, with Steve Joyce and Harry H Long. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, pp. 16–21. ISBN 978-0-7864-3581-4

- Louvish, Simon (2001). Stan and Ollie: The Roots of Comedy: The Double Life of Laurel and Hardy. New York: St. Martin's. ISBN 0-312-26651-0

- Lupack, Barbara Tepa (2020). Silent Serial Sensations: The Wharton Brothers and the Magic of Early Cinema. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1501748189

- Lussier, Tim (2018). "Bare Knees" Flapper: The Life and Films of Virginia Lee Corbin. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-7568-8

- Lyons, Timothy James (1974 [1972]). The Silent Partner: The History of the American Film Manufacturing Company, 1910–1921. New York: Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-04872-6

- Maurice, Alice (2013). The Cinema and Its Shadow: Race and Technology in Early Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-4529-3939-1

- Mayer, Geoff (2017). Encyclopedia of American Serials. Jefferson, NC:: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7762-3

- McCaffrey, Donald W., and Christopher P. Jacobs (1999). Guide to the Silent Years of American Cinema. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30345-2

- Miyao, Daisuke (2007). Sessue Hayakawa: Silent Cinema and Transnational Stardom. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822339588

- Morton, Ray (2005). King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon from Fay Wray to Peter Jackson. New York: Applause. ISBN 1-55783-669-8

- Munden, Kenneth W. (1971). The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States: Feature Films, 1921–1930. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20969-9

- Nasaw, David (2012). The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-376-3

- Nollen, Scott Allen (1991). Boris Karloff: A Critical Account of His Screen, Stage, Radio, Television. Jefferson, NC: Mcfarland. ISBN 0-89950–580-5

- Okuda, James L., and James L. Neibaur (2012). Stan Without Ollie: The Stan Laurel Solo Films, 1917–1927. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4781-7

- Quirk, Lawrence J. (1996). The Kennedys in Hollywood. Dallas: Taylor Publishing. ISBN 978-0878339341

- Rainey, Buck (1987). Heroes of the Range. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810818040

- Rainey, Buck (1999). Serials and Series: A World Filmography, 1912–1956. Jefferson, NC:: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4702-2

- Sandburg, Carl (1925). "White Fang," in The Movies Are: Carl Sandburg's Film Reviews and Essays, 1920–1928, ed. Arnie Bernstein. Chicago: Lake Claremont Press (2000), pp. 270–71. ISBN 1-893121-05-4

- Schaefer, Eric (1999). "Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!": A History of Exploitation Films, 1919–1959. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2374-5

- Sherwood, Robert Emmet (1923). The Best Moving Pictures of 1922–23. Boston: Small, Maynard.

- Shiel, Mark (2012). Hollywood Cinema and the Real Los Angeles. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-902-6

- Slide, Anthony (2013 [1998]). The New Historical Dictionary of the American Film Industry. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-579-58056-8

- Slide, Anthony (2022 [1996]). The Silent Feminists: America's First Women Directors. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-6552-2

- Solomon, Aubrey (2011). The Fox Film Corporation, 1915–1935: A History and Filmography. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6286-5

- Stumpf, Charles (2010). ZaSu Pitts: The Life and Career. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4620-9

- Sweeney, Kevin W., ed. (2007). Buster Keaton Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-962-0

- Taves, Brian. (2012). Thomas Ince: Hollywood's Independent Pioneer. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3422-2

- Valderrama, Carla (2020). This Was Hollywood: Forgotten Stars and Stories. New York: Hachette. ISBN 978-0-7624-9586-3

- Wing, Ruth, ed. (1924). The Blue Book of the Screen. Hollywood, CA: Blue Book of the Screen Inc.

External links

- The Silent Films of FBO Pictures comprehensive listing of silent features produced by FBO/Robertson-Cole and released between 1925 and 1929 (showing how many were considered lost as of 2003)

- The Early Sound Films of Radio Pictures lists FBO sound productions released in 1928 (but does not clearly indicate the several holdover FBO sound productions distributed by RKO in 1929)

- Joseph P. Kennedy Personal Papers Biographical/Historical Note includes a summary of Kennedy's FBO dealings

- The Two-Gun Man (1926)—The Surviving Reel nine-and-a-half minutes' worth of Fred Thomson and Silver King's fifteenth film for FBO