Fishery

Fishery can mean either the

Because of their economic and social importance, fisheries are governed by complex

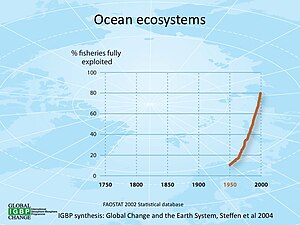

Declining fish populations, marine pollution, and the destruction of important coastal ecosystems have introduced increasing uncertainty in important fisheries worldwide, threatening economic security and food security in many parts of the world. These challenges are further complicated by the changes in the ocean caused by climate change, which may extend the range of some fisheries while dramatically reducing the sustainability of other fisheries.

Definitions

According to the

The definition often includes a combination of mammal and fish fishers in a region, the latter fishing for similar species with similar gear types.[4][5] Some government and private organizations, especially those focusing on recreational fishing include in their definitions not only the fishers, but the fish and habitats upon which the fish depend.[6]

The term fish

- In marine invertebrates, as fish.[8]

- In fisheries – the term fish is used as a collective term, and includes economic value.[3]

- True fish – The biological definition of a fish (mentioned above) is sometimes called a "true fish", the vast majority of which are aquatic life harvested in fisheries or aquaculture.[9]

Types

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

The

Close to 90% of the world's fishery catches come from oceans and seas, as opposed to inland waters. These marine catches have remained relatively stable since the mid-nineties (between 80 and 86 million tonnes).

Most fisheries are wild fisheries, but

There are commercial fisheries worldwide for finfish,

together providing a harvest of over 22 million metric tons in 1999. Many other species are harvested in smaller numbers.Economic importance

Directly or indirectly, the livelihood of over 500 million people in developing countries depends on fisheries and

In addition to commercial and subsistence fishing, recreational (sport) fishing is popular and economically important in many regions.[15]

Production

Total fish production in 2016 reached an all-time high of 171 million tonnes, of which 88 percent was utilized for direct human consumption, thanks to relatively stable capture fisheries production, reduced wastage and continued aquaculture growth. This production resulted in a record-high per capita consumption of 20.3 kg in 2016.[16] Since 1961 the annual global growth in fish consumption has been twice as high as population growth. While annual growth of aquaculture has declined in recent years, significant double-digit growth is still recorded in some countries, particularly in Africa and Asia.[16]

FAO predicted in 2018 the following major trends for the period up to 2030:[16]

- World fish production, consumption and trade are expected to increase, but with a growth rate that will slow over time.

- Despite reduced capture fisheries production in China, world capture fisheries production is projected to increase slightly through increased production in other areas if resources are properly managed. Expanding world aquaculture production, although growing more slowly than in the past, is anticipated to fill the supply–demand gap.

- Prices will all increase in nominal terms while declining in real terms, although remaining high.

- Food fish supply will increase in all regions, while per capita fish consumption is expected to decline in Africa, which raises concerns in terms of food security.

- Trade in fish and fish products is expected to increase more slowly than in the past decade, but the share of fish production that is exported is projected to remain stable.

Management

The goal of fisheries management is to produce sustainable biological, environmental and socioeconomic benefits from renewable aquatic resources. Wild fisheries are classified as renewable when the organisms of interest (e.g., fish, shellfish, amphibians, reptiles and marine mammals) produce an annual biological surplus that with judicious management can be harvested without reducing future productivity.[17] Fishery management employs activities that protect fishery resources so sustainable exploitation is possible, drawing on fisheries science and possibly including the precautionary principle.

Modern fisheries management is often referred to as a governmental system of appropriate

The integrated process of

information gathering, analysis, planning, consultation, decision-making, allocation of resources and formulation and implementation, with necessary law enforcement to ensure environmental compliance, of regulations or rules which govern fisheries activities in order to ensure the continued productivity of the resources and the accomplishment of other fisheries objectives.[20]

Global goals

International attention to these issues has been captured in Sustainable Development Goal 14 "Life Below Water" which sets goals for international policy focused on preserving coastal ecosystems and supporting more sustainable economic practices for coastal communities, including in their fishery and aquaculture practices.[21]

Law

Another important area of research covered in fisheries law is seafood safety. Each country, or region, around the world has a varying degree of seafood safety standards and regulations. These regulations can contain a large diversity of fisheries management schemes including quota or catch share systems. It is important to study seafood safety regulations around the world in order to craft policy guidelines from countries who have implemented effective schemes. Also, this body of research can identify areas of improvement for countries who have not yet been able to master efficient and effective seafood safety regulations.

Fisheries law also includes the study of aquaculture laws and regulations. Aquaculture, also known as aquafarming, is the farming of aquatic organisms, such as fish and aquatic plants. This body of research also encompasses animal feed regulations and requirements. It is important to regulate what feed is consumed by fish in order to prevent risks to human health and safety.Environmental issues

The

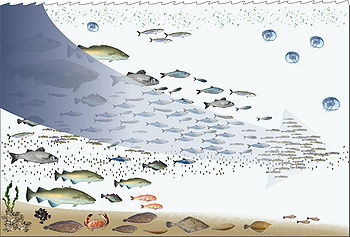

Fishing and pollution from fishing are the largest contributors to the decline in ocean health and water quality. Ghost nets, or nets abandoned in the ocean, are made of plastic and nylon and do not decompose, wreaking extreme havoc on the wildlife and ecosystems they interrupt. The ocean takes up 70% of the earth, so overfishing and hurting the marine environment affects everyone and everything on this planet. On top of the overfishing, there is a seafood shortage resulting from the mass amounts of seafood waste, as well as the

The journal

Reefs are also being destroyed by overfishing because of the huge nets that are dragged along the ocean floor while trawling. Many corals are being destroyed and, as a consequence, the ecological niche of many species is at stake.Climate change

Fisheries are affected by climate change in many ways: marine aquatic ecosystems are being affected by rising ocean temperatures,[32] ocean acidification[33] and ocean deoxygenation, while freshwater ecosystems are being impacted by changes in water temperature, water flow, and fish habitat loss.[34] These effects vary in the context of each fishery.[35] Climate change is modifying fish distributions[36] and the productivity of marine and freshwater species. Climate change is expected to lead to significant changes in the availability and trade of fish products.[37] The geopolitical and economic consequences will be significant, especially for the countries most dependent on the sector. The biggest decreases in maximum catch potential can be expected in the tropics, mostly in the South Pacific regions.[37]: iv

TheSee also

- Fisheries co-management

- Fisheries science

- National Fish Habitat Initiative

- Ocean fisheries

- Population dynamics of fisheries

- Regional Fisheries Management Organisation

- Sea Fish Industry Authority

- Tanka people

References

- ^ Fletcher, WJ; Chesson, J; Fisher, M; Sainsbury KJ; Hundloe, T; Smith, ADM and Whitworth, B (2002) The "How To" guide for wild capture fisheries. National ESD reporting framework for Australian fisheries: FRDC Project 2000/145. Page 119–120.

- ^ "fishery". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 2021-08-09.

- ^ a b FAO Fishery Glossary; "Fishery" (Entry: 98327). Rome: FAO. 2009. p. 24. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- NOAAunder Contract EA-133C-03-SE-0275

- ^ Blackhart, K; et al. (2006). NOAA Fisheries Glossary: "Fishery" (PDF) (Revised ed.). Silver Spring MD: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 16. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "Open Access Fisheries Journals | Medical Journals". www.iomcworld.org. Retrieved 2022-07-06.

- ISBN 0-471-25031-7.

- ISBN 0-07-290961-7

- ^ "Finfish – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2022-07-06.

- ^ "Scientific Facts on Fisheries". GreenFacts Website. 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- ^ New Zealand Seafood Industry Council. Mussel Farming. Archived 2008-12-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ C. Michael Hogan (2010) Overfishing, Encyclopedia of earth, topic ed. Sidney Draggan, ed. in chief C. Cleveland, National Council on Science and the Environment (NCSE), Washington, DC

- COP-15in Copenhagen, December 2009.

- ^ "Prince Charles calls for greater sustainability in fisheries". London Mercury. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-934874-16-5.

- ^ a b c In brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018 (PDF). FAO. 2018.

- ISBN 978-0632006151.

- ^ "The ecosystem approach to fisheries" (PDF). FAO. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ISBN 9789251049600.

- ^ ISBN 92-5-103962-3

- ^ United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- ^ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Fisheries Service, aboutus.htm

- ^ Kevern L. Cochrane, A Fishery Manager’s Guidebook: Management Measures and their Application, Fisheries Technical Paper 424, available at ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/004/y3427e/y3427e00.pdf

- ^ Robert Stewart, Oceanography in the 21st Century – An Online Textbook, Fisheries Issues, available at http://oceanworld.tamu.edu/resources/oceanography-book/fisheriesissues.htm Archived 2020-08-06 at the Wayback Machine

- S2CID 245009867.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2019). "Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics 2017" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-10-26.

- ^ "Global population growth, wild fish stocks, and the future of aquaculture | Shark Research & Conservation Program (SRC) | University of Miami". sharkresearch.rsmas.miami.edu. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ^ Laville, Sandra (2019-11-06). "Dumped fishing gear is biggest plastic polluter in ocean, finds report". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Kindy, David. "With Ropes and Nets, Fishing Fleets Contribute Significantly to Microplastic Pollution". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- S2CID 37235806.

- ^ Juliet Eilperin (2 November 2006). "Seafood Population Depleted by 2048, Study Finds". The Washington Post.

- Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (15 MB).

- PMID 16502612.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (2015-04-07). "Climate Action Benefits: Freshwater Fish". US EPA. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- ISSN 2296-7745.

- ^ Cheung, W.W.L.; et al. (October 2009). Redistribution of Fish Catch by Climate Change. A Summary of a New Scientific Analysis (PDF). Sea Around Us (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26.

- ^ OCLC 1078885208.

- S2CID 246522316, retrieved 2022-04-06

Free content sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO (license statement/permission). Text taken from In brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018, FAO, FAO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO (license statement/permission). Text taken from In brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018, FAO, FAO.