Fishing industry

The fishing industry is struggling with environmental and welfare issues, including overfishing and occupational safety.[3] Additionally, the combined pressures of climate change, biodiversity loss and overfishing endanger the livelihoods and food security of a substantial portion of the global population.[4]

Sectors

Commercially important finfish fisheries

|

The industry has three principal sectors that include

Other slightly different definitions exist, for example the Australian government uses:[5]

- The commercial sector: comprises enterprises and individuals associated with wild-catch or aquaculture resources and the various transformations of those resources into products for sale. It is also referred to as the seafood industry, although non-food items such as pearls are included among its products.

- The traditional sector: comprises enterprises and individuals associated with fisheries resources from which aboriginal people derive products in accordance with their traditions.

- The recreational sector: comprises enterprises and individuals associated for the purpose of recreation, sport or sustenance with fisheries resources from which products are derived that are not for sale.

Traditional

Commercial sector

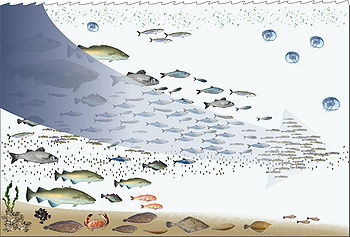

The major fishing industries are not only owned by major corporations but by small families as well.[8] In order to adapt to declining fish populations and increased demand, many commercial fishing operations have reduced the sustainability of their harvest by fishing further down the food chain. This raises concern for fishery managers and researchers, who highlight how further they say that for those reasons, the sustainability of the marine ecosystems could be in danger of collapsing.[8]

Commercial fishermen harvest a wide variety of animals. However, a very small number of species support the majority of the world's fisheries; these include

together providing a catch of over 22 million metric tons in 1999. Many other species are fished in smaller numbers. In 2016, of the 171 million tonnes of fish caught, about 88 percent or over 151 million tonnes were utilized for direct human consumption. This share has increased significantly in recent decades, as it was 67 percent in the 1960s.[9] In 2016, the greatest part of the 12 percent used for non-food purposes (about 20 million tonnes) was reduced to fishmeal and fish oil (74 percent or 15 million tonnes), while the rest (5 million tonnes) was largely utilized as material for direct feeding in aquaculture and raising of livestock and fur animals, in culture (e.g. fry, fingerlings or small adults for ongrowing), as bait, in pharmaceutical uses and for ornamental purposes.[9]World production

-

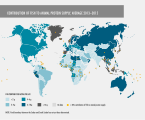

Contribution of fish to animal protein supply, average 2013–2015

Fish are harvested by commercial fishing and aquaculture.

The

Following is a table of the 2011 world fishing industry harvest in tonnes (metric tons) by capture and by aquaculture.[12]

| Capture (ton) | Aquaculture (ton) | Total (ton) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 94,574,113 | 83,729,313 | 178,303,426 |

| Aquatic plant | 1,085,143 | 20,975,361 | 22,060,504 |

| Aquatic animal | 93,488,970 | 62,753,952 | 156,202,922 |

Related industries

Once fish is caught, especially in commercial sectors, bringing the fish to consumers require a complex series of related industries.

Fish processing

Fish processing is the processing of fish delivered by commercial fisheries and fish farms. The larger fish processing companies have their own fishing fleets and independent fisheries. The products of the industry are usually sold

Fish processing can be subdivided into two categories: fish handling (the initial processing of raw fish) and fish products manufacturing. Aspects of fish processing occur on

Another natural subdivision is into primary processing involved in the filleting and freezing of fresh fish for onward distribution to fresh fish retail and catering outlets, and the secondary processing that produces chilled, frozen and canned products for the retail and catering trades.[14]

Fish products

Fisheries are estimated to currently provide 16% of the world population's

.Fish and other marine life can also be used for many other uses:

Fish derived

In the industry, the term seafood products is often used instead of fish products.

Fish marketing

Most

Environmental impact

The

Fishing and pollution from fishing are the largest contributors to the decline in ocean health and water quality. Ghost nets, or nets abandoned in the ocean, are made of plastic and nylon and do not decompose, wreaking extreme havoc on the wildlife and ecosystems they interrupt. The ocean takes up 70% of the earth, so overfishing and hurting the marine environment affects everyone and everything on this planet. On top of the overfishing, there is a seafood shortage resulting from the mass amounts of seafood waste, as well as the

The journal

Reefs are also being destroyed by overfishing because of the huge nets that are dragged along the ocean floor while trawling. Many corals are being destroyed and, as a consequence, the ecological niche of many species is at stake.Sustainable fishery

A conventional idea of a

International disputes

The ocean covers 71% of the earth's surface and 80% of the value of exploited marine resources are attributed to the fishing industry. The fishing industry has provoked various international disputes as wild fish capture rose to a peak about the end of the 20th century, and has since started a gradual decline.[32] Iceland, Japan, and Portugal are the greatest consumers of seafood per capita in the world.[citation needed]

Disputes in the Americas

Following the collapse of the Atlantic northwest cod fishery in 1992, a dispute arose between Canada and the European Union over the right to fish Greenland halibut (also known as turbot) just outside of Canada's exclusive economic zone in the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. The dispute became known as the Turbot War.[34][35] On 9 March 1995, in response to observations of foreign vessels fishing illegally in Canadian waters and using illegal equipment outside of Canada's EEZ, Canadian officials boarded and seized the Spanish trawler Estai in international waters on the Grand Banks.[36] Throughout March, the Spanish Navy deployed patrol ships to protect fishing boats in the area,[37] and Canadian forces were authorized to open fire on any Spanish vessel showing its guns.[citation needed] Canada and the European Union reached a settlement on 15 April which led to significant reforms in international fishing agreements.[38]

Disputes in Europe

Nowadays in Europe in general, countries are searching for a way to recover their fishing industries. Overfishing of EU fisheries is costing 3.2 billion euros a year and 100,000 jobs according to a report. So Europe is constantly looking for some collective actions that could be taken to prevent overfishing.[39]

Disputes in Asia

The North_Pacific_Anadromous_Fish_Commission: NPFC was established in 2015 to manage fish stocks against increasing demand. Members are Canada, Japan, Russia, the United States, and South Korea. China, Taiwan, and Vanuatu also participated in the meeting. The NPFC imposes catch limits on member countries and countries participating in the conference. A crackdown on Illegal,_unreported_and_unregulated_fishing(IUU) vendors was also requested.

Society and culture

Global goals

International policy to attempt to address these issues is captured in Sustainable Development Goal 14 ("Life below water") and its Target 14.4 on "Sustainable fishing":[41] "By 2020, effectively regulate harvesting and end overfishing, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and destructive fishing practices and implement science-based management plans, in order to restore fish stocks in the shortest time feasible, at least to levels that can produce maximum sustainable yield as determined by their biological characteristics".

Standards and labelling

The

By country

See also

- Fishery

- Fishing industry by country

- Fishing industry in the Caribbean

- List of countries by fish and seafood consumption

- Sustainable fishing

References

- ^ a b FAO Fisheries Section: Glossary: Fishing industry. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- COP-15in Copenhagen, December 2009.

- ^ Grant, Tavia (27 October 2017). "Sea Change". theglobeandmail.com. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

Despite safety gains in many other industries, fishing continues to have the highest fatality rate of any employment sector in Canada.

- ^ "Climate Change Threatens Commercial Fishers From Maine to North Carolina". www.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "Industry". Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. Archived from the original on 14 June 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Garcia, S.M. (2009). "Glossary". In Cochrane, K.; Garcia, S.M. (eds.). A fishery managers handbook. FAO and Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 473–505.

- ^ "14.b.1 Access rights for small-scale fisheries | Sustainable Development Goals". Fao.org. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ .

- ^ a b In brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018 (PDF). FAO. 2018.

- S2CID 240163091.

- ^ Larsen, Janet (16 July 2003). "Other Fish in the Sea, But For How Long?". Earth Policy Institute. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ a b "FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture - Home". Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ A Mood and P Brooke (July 2010). Estimating the Number of Fish Caught in Global Fishing Each Year. FishCount.org.uk.

- ^ Smith, David (March 2004). "Inquiry into The Future of the Scottish Fishing Industry" (PDF). Royal Society of Edinburgh. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ISSN 2511-834X.

- PMID 31145747.

- S2CID 233589867.

- PMID 26028759.

- PMID 29287362.

- S2CID 233478876.

- PMID 32075329.

- ISSN 0145-8892.

- ^ Shang, Yung C.; Leung, Pingsun; Ling, Bith-Hong (1998). "Comparative economics of shrimp farming in Asia". Aquaculture. 164 (1–4): 183–200. .

- S2CID 245009867.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2019). "Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics 2017" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2019.

- ^ "Global population growth, wild fish stocks, and the future of aquaculture | Shark Research & Conservation Program (SRC) | University of Miami". sharkresearch.rsmas.miami.edu. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ Laville, Sandra (6 November 2019). "Dumped fishing gear is biggest plastic polluter in ocean, finds report". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Kindy, David. "With Ropes and Nets, Fishing Fleets Contribute Significantly to Microplastic Pollution". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- S2CID 37235806.

- ^ Juliet Eilperin (2 November 2006). "Seafood Population Depleted by 2048, Study Finds". The Washington Post.

- ^ Hilborn, Ray (2005) "Are Sustainable Fisheries Achievable?" Chapter 15, pp. 247–259, in Norse and Crowder (2005).

- ^ Millennium Ecosystem Assessment

- ^ "In Mackerel's Plunder, Hints of Epic Fish Collapse". International Herald Tribune. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2016 – via The New York Times.

- ^ Anderson, Lisa (19 March 1995). "Depleted fish stocks spark Canada's turbot war with Spain". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "Court backs Canada's seizure of trawler during 'turbot war'". CBC News. 27 July 2005. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Swardson, Anne (10 March 1995). "Canada Fires Warning Shots; Seizes Spanish Fishing Boat". The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Tremlett, Giles (23 March 1995). "Spanish trawler Estai reaches port". United Press International. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Damanaki, Maria (6 September 2010). "Answer to Question No E-4682/10". European Parliament. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Overfishing 'costs EU £2.7bn each year'". BBC News. 10 February 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Urbina, Ian. "The deadly secret of China's invisible armada". www.nbcnews.com. NBC News. Retrieved 11 August 2020

- ^ United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- ^ "MSC standards — MSC". Msc.org. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ "What is a Conformity Assessment Body". TCAB - Trust Conformity Assessment Body. 16 February 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2022.