Fleetwood Park Racetrack

Morrisania, Bronx, New York, US | |

| Coordinates | 40°49′48″N 73°54′54″W / 40.830°N 73.915°W |

|---|---|

| Operated by | New York Driving Club |

| Date opened | June 8, 1871 |

| Date closed | January 1, 1898 |

| Race type | Trotting |

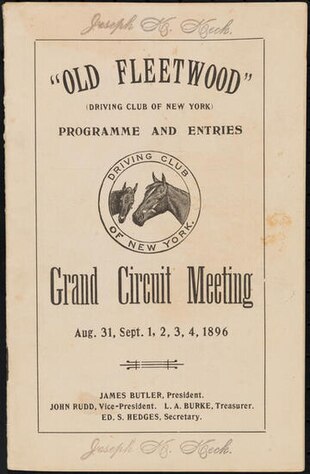

Fleetwood Park was a 19th-century harness racing (trotting) track in what is now the Morrisania section of the Bronx in New York, United States. The races held there were a popular form of entertainment, drawing crowds as large as 10,000 from the surrounding area. The one-mile (1.6 km) course described an unusual shape, with four turns in one direction and one in the other. For the last five years of operation, Fleetwood was part of trotting's Grand Circuit, one travel guide calling it "the most famous trotting track in the country".

The track operated under several managements between 1870 and 1898. Most notable was the New York Driving Club, consisting of many wealthy New York businessmen, including members of the

For most of its history, the track failed to turn a profit, the shortfall being made up annually from financial assessments of the membership. Economic pressures forced the track to close in 1898, and within two years the property was being subdivided into residential building lots. One of the few remaining vestiges of the track is the meandering route of 167th Street, which runs along a portion of the old racecourse.

Description

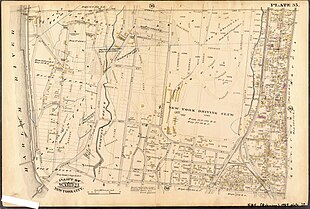

Fleetwood Park was located in the town of Morrisania, Westchester County (now the Morrisania section of the Bronx), on the west side of Railroad (now Park) Avenue.[1][2] This area lies between Webster and Sheridan Avenues and 165th and 167th Streets on the modern Bronx street grid.[3]: 705 The covered grandstand,[4] clubhouse, judges' stand, and other buildings were clustered along the southwest corner of the track, adjacent to Sheridan Avenue.[1] The clubhouse, a French Second Empire–style building, had a view of the track from above.[4] Valentine's Manual described the park as "the broad acres of that well-known rendezvous of all lovers of the turf";[5] the New York Times variously described the track as "oddly-shaped"[6] and "queer-shaped".[7] An 1885 map shows it as roughly rectangular with a bulge on one side, yielding five turns – four to the left and one to the right, if run counter-clockwise.[1] Modern-day 167th Street diverges from the otherwise rectilinear street grid with the oblique portion of the street following the northern leg of the racecourse.[4] Another oddity was that the track was not level, dropping approximately nine feet (2.7 m) in the first half-mile.[8]: 165

As many as 10,000 spectators attended races at Fleetwood.

When races were not being held, the grounds were used for other activities. In 1888, a winter carnival was set up, with toboggan slides, lighting, and music;

Geology

In an 1881 study of the geology of the region, J. D. Dana described Fleetwood Park as "low and nearly flat, except its western side"[19]: 440 and theorized this (along with other features of the area) was caused by limestone belts which were subject to easy erosion.[20] Dana writes:[19]: 433

The limestone area No. 2 ... joins that already described through the region of Fleetwood Park ... The northern limit of the belt is about two miles north of McComb's (or Central) Bridge. At this north extremity ... two valleys come up from the south and meet [the more eastern one] passes into Fleetwood Park. The limestone of Morrisania extends westward over three-fourths of Fleetwood Park and then northward ... The high land between the two valleys forming the western side of Fleetwood Park consists mainly of schist.

History

Before Fleetwood Park

Horses had been raced in the Fleetwood Park area as early as 1750, on a racecourse built by Staats Long Morris who took advantage of the relatively level land.[4] The exact location of his track is unclear; it may have occupied the site which eventually became Fleetwood Park, or it may have been further north, adjacent to what is now Claremont Park.[21] It is unknown how long the Morris track lasted, and there is no further record of racing in the immediate area until 1870.[4] Two other racetracks operated in the Bronx at around the same time. Jerome Park, a thoroughbred track, was opened in 1866 and operated until 1890, when it was condemned by the city and the land repurposed to build Jerome Park Reservoir.[22] Morris Park which operated from 1889[23] to 1904,[24] also for thoroughbreds, was located in what is now the Morris Park neighborhood of the Bronx.[25][26]: 773, Morris Park (i)

The name Fleetwood has been associated with this area since at least 1850, when the New York Industrial Home Association No. 1 was organized as a

Fleetwood Park era

In 1870, William Morris leased part of his estate to two brothers, Henry and Philip Dater,

Post-closure

The track was permanently closed on January 1, 1898, when the city began constructing streets on the property.[4][3]: 705 By the end of that month, the New York Driving Club had met to consider building a new track, two possible locations being discussed. One site of 105 acres (42 ha) was near Mount Vernon, served by William's Bridge Road, Boston Road, and the Harlem River Railroad. The other site, with 77.7 acres (31.4 ha), was about 2 miles (3.2 km) closer to the city, along the Bronx and Pelham Parkway, not far from the Morris Park track. The latter was preferred by most of the membership.[40][41][42] Alfred De Cordova, who had been elected president, stated:[40]

We intend to give the new city a driving track that will be a credit to it. The grand stand and stables will be as commodious as any in the country, and when the track is completed the horsemen will see old Fleetwood rise phoenixlike, only the new track will be greatly superior to the old.

Cordova noted that while the men in the club were "wealthy enough and ardent enough"[40] they could raise the entire cost of the new track by themselves, four or five members being able to immediately contribute $150,000 (equivalent to $5,500,000 in 2023)[note 1] the club intended to issue bonds.[40] It was estimated that the total cost to complete the track would be $280,000 (equivalent to $10,300,000 in 2023).[42][note 1] Despite these proclamations, by the end of 1898, it was announced that the new track would be built in Yonkers and operated by William H. Clark.[43] The following year, the Empire City Trotting Club began operations at Yonkers Raceway.[44][45] Dirt from the old track was used to grade and fill the private park being installed by Andrew Carnegie for the new Fifth Avenue residence he was building in Manhattan.[46]

In 1898 (the same year Fleetwood Park closed) the

... a $5 million bread-and-circuses project built to serve both the rich – who wanted a racing ground for their fast trotters – and the not-so-rich, who were supposed to watch.

Several years earlier, Robert Bonner had written:[8]: 166

Interest in trotting has not fallen off but owners of horses remain away from Fleetwood because the streets and roads leading to the place are bad and hard on the animals. And another cause for the lack of interest in Fleetwood is the fact that the track is not as good as it might be. But I am sure when the new Speedway is completed there will be a decided revival in trotting.

By the 1910s, motorcar racing had eclipsed trotting and use of the speedway by carriages had fallen to fewer than 100 per day in 1916 and fewer than 20 per day in 1918. Automobiles were allowed onto the speedway in 1919. In the mid-20th century it was incorporated into the modern-day Harlem River Drive.[47][48]

Within a few years of Fleetwood's closing, the property was divided into building lots by real estate developers.[49] By August 1900, the clubhouse was the only structure left standing, and the Union Republican Club considered moving the building to their newly purchased property on 164th Street.[50][51][52] The first part of the property to be developed was the block of Clay Avenue between 165th and 166th Streets, with thirty-two buildings (twenty-eight Warren C. Dickerson–designed semi-detached houses, plus three apartment buildings, and one private residence) erected between 1901 and 1910. In 1994, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated this block the Clay Avenue Historic District.[4] What is modern-day Teller Avenue was originally named Fleetwood Avenue, after the track. The name was later changed to Teller Avenue, honoring Richard H. Teller, a member of the 1868 commission which authorized the first official street map of Morrisania, published in 1871.[53]: 237 [54]

Operation

For most of the track's lifetime, trotting races were run on the 1-mile (1.6 km)[9] (one source says 1.25-mile (2.0 km))[53]: 117 oval by the New York Driving Club.[3]: 704–705 In 1892 The Sun's Guide described Fleetwood as "For a time ... the most famous trotting track in the country".[10]: 80 The Guide noted, however, that interest in harness racing by horse owners had waned, the track had "gone into a decline"[10]: 80 and that the single annual meeting was "not an important meeting", not being part of harness racing's Grand Circuit.[10]: 80

The next year, the New York Driving Club was admitted to the Grand Circuit, along with another club in Detroit. This brought the Grand Circuit up to nine clubs: Pittsburgh, Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, Rochester, Springfield (Massachusetts), Hartford, New York, and Philadelphia, allowing it to better compete with the Western-Southern Circuit. The clubs also agreed to increase cooperation with each other and made it more difficult to expand the circuit by requiring a two-thirds vote of existing members to admit any new members.[55][56] Improvements in preparation for the track's first Grand Circuit meeting included upgrading the grandstand, painting fences, trimming foliage, and enlarging the band stand. A new starter, Frank Walker, was hired with the hopes of speeding up the scoring process.[57]

The Sun's Guide lamented that the track was "famous more for the men who sent their horses there than for great races".[10]: 80 Members of the club included William K. Vanderbilt, William Rockefeller, William C. Whitney, Leonard Jerome,[4] Oliver Belmont, Cornelius Bliss, C. Oliver Iselin, Abram Hewitt[58] and Nathan Straus.[36] The membership varied significantly from year to year; reported as over 500 in 1886, it was down to 290 in 1891 and back up to 400 in 1892.[36][59] Robert Bonner, owner and publisher of the New York Ledger and trotting aficionado had his stables nearby.[3]: 705 Robert's younger brother, David,[60]: 339 was also a member of the New York Driving Club and at one time served as its president.[37] Robert was well known for paying large sums for horses; in 1884 he bought Maud S. from William H. Vanderbilt (William K.'s father) for $40,000 (equivalent to $1,400,000 in 2023).[61][62][note 1] Five years later, he purchased Sunol from Leland Stanford for an unknown price only disclosed as being higher than that of Maud S.[63]

Other notable attendees included former US president Ulysses S. Grant,[64] who sometimes also drove horses at the track.[21] Grant's skill with horses was well-known; he could ride, drive and train them as required.[65] Modern-day Grant Avenue, named after the president, bisects the old racecourse; the track crossed it at what is now East 164th Street.[53]: 116–117 Also named after the president was the Grant Hotel, frequented by the jockeys. This was located across the contemporary College Avenue from Robert Bonner's house, which was at the foot of modern-day Bonner Place.[21][53]: 33

Many well-known horses competed at Fleetwood. Perhaps the most famous was Maud S. (1874–1900), who held seven world-record times set over the span of six years.[61][66] She was renowned for the high price Bonner paid for her.[67][68] Alix (1888–1901), known as the "Queen of the Turf", was the world trotting champion for six years,[69][70] and Directum (1889–1909) at one time held the record for fastest heat by a four-year-old.[69][71] Goldsmith Maid (1857–1885) earned an estimated $364,200 (equivalent to $12,350,000 in 2023)[note 1] over 13 years, which was a prize-money record for half a century.[72][73] Jay-Eye-See (1878–1909) and St. Julien (1869–1894) raced against each other on September 29, 1883.[74][75][76] Nancy Hanks (1886–1915), owned by John Malcolm Forbes, held a series of world-record times including what the New York Times called "the greatest performance ever made in harness" at Fleetwood on September 1, 1893.[77][78]

The club lost money most years. In 1893, the New York Times wrote:[79]

Year in and year out the Treasurer of Gotham's driving club has been the one official who has accepted the post with reluctance and relinquished it with a sigh of relief; happy if he could leave his financial statement painfully balanced by an assessment on the members.

The first year of profitable operations was 1893, when the Grand Circuit meeting and "special day profits"[79] provided sufficient income. Major expenses were ground rent ($8,000, equivalent to $270,000 in 2023) and labor ($4,178, equivalent to $142,000 in 2023). Income was mostly from initiation fees, dues, and "transfer members" ($12,225, equivalent to $415,000 in 2023) and stall rent ($4,408, equivalent to $149,000 in 2023). The consolidated meeting and special day earned $1,183 (equivalent to $40,000 in 2023) and $1,077 (equivalent to $37,000 in 2023) respectively. Sale of manure brought in another $10 that year (equivalent to $339 in 2023).[79][note 1]

Charter Oak Stakes

Charter Oak Park, a Grand Circuit harness racing track in Hartford, Connecticut, had opened in 1873.[80][81] Twenty years later, Charter Oak canceled racing due to a "new law relating to pool selling and purse racing"[82] and the Charter Oaks Stakes, first run in 1883, was transferred to Fleetwood.[83][84][85] The Breeder and Sportsman wrote:[86]

Fleetwood will see very lively days this season. After much deliberation the Driving Club, of New York, and the Charter Oak Club, of Hartford, have decided to consolidate their Grand Circuit meetings this year and to have them decided at the New York track, August 28th to September 4th. This combination will result in one of the grandest trotting meetings ever held in the world, and it will certainly surpass anything New York has ever before been treated to.

Two weeks later editor Joseph Simpson explained in the same publication:[87]

Several of the State Legislatures have recently manifested an inclination to abolish racing in all its forms, because of the abuses to which it had been subject. Restrictive laws have been passed in Maine, in Connecticut, in New Jersey, and in Illinois ... In Connecticut the feeling became so powerful that the Legislature absolutely prohibited any public contests of skill or speed in which a premium is awarded. Horses cannot, in that State, trot either in purse or stake races, and the Charter Oak Association, one of the greatest trotting organizations in America, has been under the necessity of trotting its races at Fleetwood.

The next year, the race was back at Charter Oak but, unlike all previous Grand Circuit meetings, with no betting at the track. The gate admission fee was waived in an attempt to draw spectators.[88]

Incidents

On January 12, 1870, two men were seriously injured when a blasting charge exploded prematurely. The men had prepared the charge and were about to ignite it when it exploded for unknown reasons.[89] On March 2, 1870, there was another explosion. Nitroglycerin—being used to clear rocks the previous day—had leaked into rock fissures beyond the intended location; this exploded when a crowbar caused a spark. One man was killed and several others were seriously injured.[90]

The track also suffered fire damage. On June 15, 1873, an early morning fire in the stables destroyed 48 stalls, causing an estimated $12,000 (equivalent to $305,000 in 2023)[note 1] damage to the building, plus unknown damages to sulkies and other racing gear. Two horses worth a total of $11,000 (equivalent to $280,000 in 2023)[note 1] were killed.[91] Another fire, on October 15, 1893, was discovered at 8:00 am. Two horses, one worth $10,000 (equivalent to $339,000 in 2023),[note 1] perished; another horse and his keeper were injured. Total damages to the buildings and horses was $20,000 (equivalent to $509,000 in 2023).[92][note 1] Forty stalls were destroyed which the club intended to rebuild along with an additional 25 to 30 stalls, bringing the total to about 300.[93][note 2]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ The cited source refers to "The fire last November". This appears to be an error and should say "October".

References

- ^ a b c Robinson, Elisha; Pidgeon, Roger (1885). "Plate 35: Bounded by .....N. Third Avenue, 161st Street, Jerome Avenue, Harlem River and Depot Place". E. Robinson Co. Archived from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022 – via The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

- ^ a b Ultan, Lloyd (September 26 – October 2, 2013). "The Other Racetrack". Riverdale Review. Vol. XX, no. 40. p. 5. Archived from the original on December 9, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ OCLC 1156399140 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Dolkart, Andrew S. (April 5, 1994). Pearson, Marjorie; Urbanelli, Elisa (eds.). Clay Avenue Historic District (PDF) (Report). New York: The Landmarks Preservation Commission. pp. 2–5. LP-1898. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 3, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- OCLC 1008770607. Archived from the originalon February 14, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2023 – via Columbia University Libraries Digital Collections.

- from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ LCCN 79-86709 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ ISSN 2474-3224. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021 – via Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ OCLC 1066578114. Archivedfrom the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-57167-254-4. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2022 – via Google Books.

- OCLC 10081652. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2022 – via Google Books.

- OCLC 22091780. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved April 21, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ The City Record: Motions, Ordinances and Resolutions (PDF) (Report). New York: Board of City Record. April 26, 1906. p. 3964. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2023. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- from the original on December 3, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- from the original on December 3, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ^ ISSN 2835-6764. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved August 29, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Hathi Trust.

- ^ a b c Kearns, Betsy W.; Saunders, Cece; Schaefer, Richard (September 1994). Archaeological Assessment, Criminal Court Facility, Block 2444 and 2445, Morrisania, Bronx (PDF) (Report). New York: City of New York Department of General Services. p. 15. tDAR (the Digital Archeological Record) id 362558. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 20, 2023. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "Jerome Park". NYC Department of Parks & Recreation. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- from the original on August 21, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- from the original on August 21, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ^ "Bronx History at the Bronx Library Center: The Morris Park Racecourse". The New York Public Library. Archived from the original on October 12, 2023. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ ISBN 0-300-05536-6. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ OCLC 1046597892 – via Internet Archive.

- Hathi Trust.

- newspapers.com.

- newspapers.com.

- from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- OL 16491842W – via Internet Archive.

- LCCN 14016972 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Hilton, Alexandra (May 25, 2017). "The Last County: The Bronx". NYC Department of Records & Information Services. Archived from the original on October 29, 2022. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- from the original on December 9, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- LCCN sn84031792. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021 – via Library of Congress: Journaling America.

- OCLC 1487139. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ from the original on August 21, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- from the original on August 21, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ from the original on August 21, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- from the original on August 21, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ "Yonkers Raceway". Yonkers Raceway. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- ^ "Andrew Carnegie's Park". Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. April 12, 1901. p. 1. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ from the original on March 8, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ "New York's Harlem River Speedway and the Gilded Age". Harness Racing Museum & Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- from the original on December 9, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- (PDF) from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2022 – via Columbia University Library.

- from the original on August 21, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- from the original on August 24, 2023. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ .

- ^ Spooner, Walter Whipple (1900). Westchester County, New York: Biographical. New York History Company. p. 99. Archived from the original on October 11, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- from the original on October 25, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ISSN 2836-6115. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023 – via Google Books.

- from the original on October 11, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- OL 6718933M.

- ^ a b "Maud S." Harness Racing Museum & Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ "Know Your Vanderbilts". Vanderbilt University News. March 12, 2014. Archived from the original on September 17, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Ulysses S. Grant's Horsemanship". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. April 21, 2022. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- from the original on October 11, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "Alix". Harness Racing Museum & Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "Directum". Harness Racing Museum & Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on February 1, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "Goldsmith Maid". Harness Racing Museum & Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "Jay-Eye-See". Harness Racing Museum & Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "St. Julien". Harness Racing Museum & Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on February 5, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "The Great Race: Jay Eye See Downs St. Julien in Three Straight Heats". Pontiac Bill Poster. October 3, 1883. p. 8. Archived from the original on October 25, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023 – via Digital Michigan Newspapers Collection.

- from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "Nancy Hanks". Harness Racing Museum & Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ Rapacz, Andrea (August 28, 2020). "And They're Off!: Harness Racing at Charter Oak Park". Connecticut History. Connecticut Humanities. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Fasig, William Benjamin; Gocher, William Henry (1903). Fasig's Tales of the Turf: With Memoir in which is Included a History of the Cleveland Driving Park, a Review of the Grand Circuit, how the Gentlemen's Driving Club of Cleveland was Started, and a Sketch of Fasig's Sale Business. Hartford: W.H. Gocher. p. 20. Archived from the original on October 11, 2023. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- from the original on August 25, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "Grand Circuit Meeting at Charter Oak Park". The Catholic Transcript. Hartford, Connecticut. August 8, 1929. p. 2. Retrieved August 25, 2023 – via JSTOR.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- from the original on August 25, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "Fleetwood Park, New York". The Breeder and Sportsman. XXIII (2). San Francisco: 27. July 8, 1893 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Simpson, Joseph Cairn (August 28, 1893). "Special Department". The Breeder and Sportsman. XXIII (4): 85 – via Internet Archive.

- from the original on August 25, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2022.