Foreign relations of imperial China

The foreign relations of

Following the fall of

Following the collapse of the Yuan dynasty and the formation of the

The dissolution of the Mongol empire in the fourteenth century made Central Asian trade routes dangerous and forced Western European powers to explore ocean routes. Following the Portuguese and

Background

In premodern times, the theory of foreign relations of China held that the

There were several periods when

Nevertheless, China was a center of trade from early on in its history. Many of China's interactions with the outside world came via the Silk Road. This included, during the 2nd century AD, contact with representatives of the Roman Empire, and during the 13th century, the visits of Venetian traveler Marco Polo.

Chinese foreign policy was usually aimed at containing the threat of so-called "barbarian" invaders (such as the Xiongnu, Mongols, and Jurchen) from the north. This could be done by military means, such as an active offense (campaigns into the north) or a more passive defense (as exemplified by the Great Wall of China). The Chinese also arranged marriage alliances known as heqin, or "peace marriages."

Chinese officers distinguished between "matured/familiar barbarians" (foreigners influenced by Chinese culture) and "raw barbarians".[citation needed]

In many periods, Chinese foreign policy was especially assertive. One such case was exemplified by the

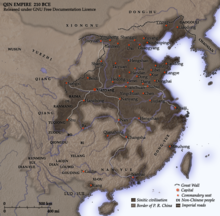

Qin dynasty

Although many kings of the

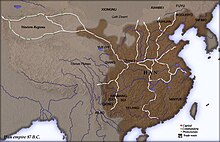

Han dynasty

The time of the

Yet Chinese trading missions to follow were not limited to travelling across land and terrain. During the 2nd century BC, the Chinese had sailed past

The Han general

Period of Disunity

Although introduced during the Han dynasty, the chaotic, divisionary

Three Kingdoms

The

Jin dynasty

The

Southern and Northern dynasties

Like the Three Kingdoms period before it, the

Sui dynasty

Yang Jian (Emperor Wen) ruled in northern China from 581, and conquered the Chen dynasty in the south by 589, hence reunifying China under the Sui dynasty (581–618). He and his successor Emperor Yang initiated several military campaigns.

The Grand Canal was completed during the Sui dynasty, enhancing indigenous trade between northern and southern China by canal and river traffic.

One of the diplomatic highlights of this short-lived dynastic period was

Prince Shōtoku made his queen Suiko call herself Empress, and claimed an equal footing with the Chinese Emperor who regarded himself as the only Emperor in the world at that time. Thus Shōtoku broke with Chinese principle that a non-Chinese sovereign was only allowed to call himself king but not emperor.

Emperor Yang thought of this Japanese behavior as 'insolent', because it opposed his Sinocentric worldview, but finally, he had to accept it and send an embassy to Japan in the next year as he had to avoid conflict with Japan to prepare for the conquest of Goguryeo.

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (618–907) represents another high point for China in terms of its military might, conquest and establishment of vassals and tributaries, foreign trade, and its central political position and preeminent cultural status in East Asia.

One of the most ambitious rulers of the dynasty was

In a formidable alliance with the Korean kingdom

Chinese trade relations during the Tang dynasty was extended further west to the

Although the reign of

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms

The

Song dynasty

The Chinese political theory of China being the center of world diplomacy was largely accepted in East Asia, except in periods of Chinese weakness such as the Song dynasty (960–1279).

During the

The imperial court of the

With powerful dynasties to its north such as the Tangut-led Western Xia, the Song dynasty was forced to engage in skillful diplomacy. The famous statesmen and scientists Shen Kuo (1031–1095) and Su Song (1020–1101) were both sent as Song ambassadors to the Liao dynasty in order to settle border disputes. Shen Kuo asserted the Song dynasty's rightful borders in the north by dredging up old archived court documents and signed agreements between the Song and Liao dynasties. Su Song asserted the Song dynasty's rightful borders in a similar way, only he used his extensive knowledge of cartography and maps to solve a heated border dispute.

Chinese

Although the golden age of Chinese Buddhism ended during the Tang dynasty, there were still influential Chinese Buddhist monks. This included the Zen Buddhist monk Wuzhun Shifan (1178–1249), who taught Japanese disciples such as Enni Ben'en (1201–1280). After returning to Japan from China, the latter contributed to the spread of Zen teaching in Japan and aided in the establishment of Tōfuku-ji.

Yuan dynasty

The

It was the Yuan founding emperor Kublai who finally conquered the Southern Song dynasty in 1279. Kublai was an ambitious leader who used ethnic Korean, Han, and Mongol troops to invade Japan on two separate occasions, yet both campaigns were ultimately failures.

The Yuan dynasty continued the maritime trading legacy of the Tang and Song dynasties. The Yuan ship captain known as Wang Dayuan (fl. 1328–1339) was the first from China to travel by sea through the Mediterranean upon his visit to Morocco in North Africa. One of the diplomatic highlights of this period was the Chinese embassy to the Khmer Empire under Indravarman III, led by the envoy Zhou Daguan (1266–1346) from the years 1296 to 1297. In his report to the Yuan court, Zhou Daguan described places such as Angkor Wat and everyday life of the Khmer Empire. It was during the early years of Kublai Khan's reign that Marco Polo (1254–1324) visited China, presumably as far as the previous Song capital at Hangzhou, which he described with a great deal of admiration for its scenic beauty.

Ming dynasty

The

The Hongwu Emperor allowed foreign envoys to visit the capitals at

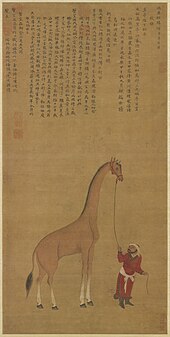

The greatest diplomatic highlights of the Ming period were the enormous

Large tributary missions such as these were halted after Zheng He, with periods of isolationism in the Ming dynasty, coupled with the need to defend

In 1524, Beijing was visited by representatives of the Ottoman Empire.[10]

Meanwhile, the Chinese under the

The decline of Ming China's economy by inflation was made worse by crop failure, famine, sudden plague, and

The first

Early Qing dynasty to 1800

The long-lasting Chinese Rites controversy of the 17th and 18th centuries led the pope in 1704 to reverse the Jesuit position and reject any recognition of traditional Chinese rituals regarding ancestors and Confucianism. The Emperor thereupon banished all missionaries who followed the pope's policy.[14] The pope's decision was finally reversed in 1939.[15]

One issue facing Western embassies to China was the act of prostration known as the kowtow. Western diplomats understood that kowtowing meant accepting the superiority of the Emperor of China over their own monarchs, an act which they found unacceptable. In 1665, Russian explorers met the Manchus in what is today northeastern China. Using the common language of Latin, which the Chinese had learned from Jesuit missionaries, the Kangxi Emperor of China and Tsar Peter I of the Russian Empire negotiated the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, which delineated the borders between Russia and China, some sections of which still exist today.[16]

Russia was not dealt with through the Ministry of Tributary Affairs, but rather through the same ministry as the problematic Mongols, which served to acknowledge Russia's status as a nontributary nation. From then on, the Chinese worldview of all other nations as tributaries began to unravel.

In 1793, the Qianlong Emperor rejected an offer of expanded trade and foreign relations by the British diplomat George Macartney. A Dutch embassy was the last occasion in which any European appeared before the Chinese imperial court within the context of traditional Chinese imperial foreign relations.[17]

While maintaining foreign relations is crucial in safeguarding economic and political strength, the Imperial Court had little incentive to appease the European nations at the time. Evidenced in the book The Great Divergence by Professor Kenneth Pomeranz, the infrastructure surrounding China's economy was far more durable than its European counterparts. The capability for multiple Chinese markets to satisfy domestic needs and compete globally[18] enabled independent innovation and development outside the European sphere of influence. Given the high quality of life, adequate sanitation, and a strong internal agricultural sector,[18] the Chinese government had no significant motivation to satisfy any demands imposed by western powers.

Representing Dutch and Dutch East India Company interests, Isaac Titsingh traveled to Beijing in 1794–96 for celebrations marking the 60th anniversary of the Qianlong Emperor's reign.[19] The Titsingh delegation also included the Dutch-American Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest,[20] whose detailed description of this embassy to the Chinese imperial court was soon after published in the United States and Europe. Titsingh's French translator, Chrétien-Louis-Joseph de Guignes published his own account of the Titsingh mission in 1808. Voyage a Pékin, Manille et l'Ile de France provided an alternate perspective and a counterpoint to other reports which were then circulating. Titsingh himself died before he could publish his version of events.

The Chinese worldview changed very little during the Qing dynasty as China's sinocentric perspectives continued to be informed and reinforced by deliberate policies and practices designed to minimize any evidence of its growing weakness and West's evolving power. After the Titsingh mission, no further non-Asian ambassadors were allowed even to approach the Qing capital until the consequences of the First and Second Opium Wars changed everything. For the later history see Foreign relations of China#History, List of diplomatic missions of the Qing dynasty, and Dates of establishment of diplomatic relations with the Qing dynasty.

See also

- Official communications in imperial China

- Imperial Chinese tributary system

- Portraits of Periodical Offering

- List of tributaries of imperial China

- List of recipients of tribute from China

- Pax Sinica

- Adoption of Chinese literary culture

- History of the Great Wall of China

- Zongli Yamen

- China-Iran relations

- Sino-Roman relations

- China–Holy See relations

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Mark Edward Lewis, The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han (2007).

- ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-12433-1.

- ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- ISBN 978-0-674-03109-8.

- ^ Thomas, R. D. A trip on the West River: new going and coming = 新往來. Canton: China Baptist Publication Society, 1903. Call no: DS710 T366 1903.

- ^ Geoff Wade, "The Zheng He voyages: a reassessment." Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (2005): 37-58. in JSTOR

- ^ George Bryan Souza, The Survival of Empire: Portuguese Trade and Society in China and the South China Sea 1630-1754 (2004).

- ^ Richard Von Glahn, "Myth and reality of China's seventeenth-century monetary crisis." Journal of Economic History 56#2 (1996): 429-454.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 141.

- ^ Samuel Hawley, The Imjin War: Japan's Sixteenth-Century Invasion of Korea and Attempt to Conquer China (2014).

- ^ Angela N.S. Hsi, "Wu San-kuei in 1644: a Reappraisal." Journal of Asian Studies 34#2 (1975): 443-453.

- ^ Florence C. Hsia, Sojourners in a strange land: Jesuits and their scientific missions in late imperial China (U of Chicago Press, 2009).

- ISBN 0472112082.

- ^ Paul Rule, "The Chinese Rites Controversy: A Long Lasting Controversy in Sino-Western Cultural History." Pacific Rim Report 32 (2004): 2-8. online Archived 2021-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ V. S. Frank, "The Territorial Terms of the Sino-Russian Treaty of Nerchinsk, 1689." Pacific Historical Review 16.3 (1947): 265-270. online

- ^ O'Neil, Patricia O. (1995). Missed Opportunities: Late 18th Century Chinese Relations with England and the Netherlands. [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington]

- ^ ISBN 9780691090108.

- ^ Duyvendak, J.J.L. (1937). 'The Last Dutch Embassy to the Chinese Court (1794–1795).' T'oung Pao 33:1-137.

- ^ van Braam Houckgeest, A.E. (1797). Voyage de l'ambassade de la Compagnie des Indes Orientales hollandaises vers l'empereur de la Chine, dans les années 1794 et 1795 Philadelphia; _____. (1798). An authentic account of the embassy of the Dutch East-India Company, to the court of the emperor of China, in the years 1794 and 1795. London.

Sources

- Primary sources

- van Braam Houckgeest, Andreas Everardus. (1798). An authentic account of the embassy of the Dutch East-India Company, to the court of the emperor of China, in the years 1794 and 1795. London. Vol. I. Archived 2009-02-15 at the Wayback Machine Digitized by University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives, "China Through Western Eyes."

- de Guignes, Chrétien-Louis-Joseph (1808). Voyage a Pékin, Manille et l'Ile de France. Paris.

- Robbins, Helen Henrietta Macartney (1908). Our First Ambassador to China: An Account of the Life of George, Earl of Macartney with Extracts from His Letters, and the Narrative of His Experiences in China, as Told by Himself, 1737–1806, from Hitherto Unpublished Correspondence and Documents. Archived 2018-10-06 at the Wayback Machine London : John Murray. [digitized by University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives, "China Through Western Eyes." ]

- Satow, Ernest (2006). The Diaries of Sir Ernest Satow, British Envoy in Peking (1900–06). New York.

Further reading

- Brook, Timothy. Great State: China and the World (2020) excerpt also online review

- Dmytryshyn, Basil. "Russian expansion to the Pacific, 1580-1700: a historiographical review." Slavic Studies 25 (1980): 1-25. online

- Duyvendak, J.J.L. (1937). "The Last Dutch Embassy to the Chinese Court (1794–1795)." T'oung Pao, 33:1-137. online

- Harrison, Henrietta (2017). "The Qianlong Emperor's Letter to George Iii and the Early Twentieth Century Origins of Ideas About Traditional China's Foreign Relations". American Historical Review. 122 (3): 680–701. .

- Kang, David C (2010). East Asia before the West: Five Centuries of Trade and Tribute. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231153188.

- Keevak, Michael (2017). Embassies to China: Diplomacy and Cultural Encounters Before the Opium Wars (Palgrave Macmillan).

- Kim, Bongjin. "Rethinking of the Pre-Modern East Asian Region Order." Journal of East Asian Studies 2.02 (2002): 67–101.

- Lee, Ji-Young. China's Hegemony: Four Hundred Years of East Asian Domination (Columbia UP, 2016).

- O'Neil, Patricia O. (1995). Missed Opportunities: Late 18th Century Chinese Relations with England and the Netherlands. (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington).

- Rockhill, William Woodville. "Diplomatic Missions to the Court of China: The Kotow Question I," American Historical Review, 2#3 (1897), pp. 427–442; "Diplomatic Missions to the Court of China: The Kotow Question II," American Historical Review, 2#4 (1897) pp. 627–643.

- Vogel, Ezra F. China and Japan: Facing History (2019) excerpt

- Waley-Cohen, Johanna (1999). The Sextants of Beijing: Global Currents in Chinese History. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Westad, Odd Arne. Restless Empire: China and the World since 1750 (2012) 515pp excerpt

- Wills, John E., ed. (2011). China and Maritime Europe, 1500-1800: Trade, Settlement, Diplomacy, and Missions. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521432603.

- Wills, John E., ed. (2010). Past and Present in China's Foreign Policy: From "Tribute System" to "Peaceful Rise". Portland, ME: MerwinAsia. ISBN 9781878282873.